Update From the Military Commissions: A Big September in the 9/11 Case

Last month, the military commission for the matter of United States v. Khalid Shaikh Mohammad et al. (i.e., the 9/11 trial) held a marathon three weeks of nearly back-to-back hearings. After being held up by delays in the publication and release of relevant transcripts, this post summarizes these proceedings and identifies several areas of potential interest, including testimony from two FBI special agents regarding their interviews with the defendants and their prior knowledge of alleged torture by the CIA.

September 9

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Last month, the military commission for the matter of United States v. Khalid Shaikh Mohammad et al. (i.e., the 9/11 trial) held a marathon three weeks of nearly back-to-back hearings. After being held up by delays in the publication and release of relevant transcripts, this post summarizes these proceedings and identifies several areas of potential interest, including testimony from two FBI special agents regarding their interviews with the defendants and their prior knowledge of alleged torture by the CIA.

September 9

Presiding military judge Col. Shane Cohen began the week’s sessions in pro forma fashion by noting for the record those present and informing the accused of their rights. He then briefly summarized a conference detaining recent changes to the defense team before turning to a discussion of classification guidance. David Nevin, counsel for defendant Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, argued that, though the military commission cannot classify or declassify information, the presiding military judge may determine that the fairness of the proceedings is jeopardized by a failure to declassify information. Cohen agreed with this assessment of the commission’s authorities, and stated that he can order the provision of discoverable information or grant some other type of relief as appropriate to ensure a fair trial.

James Connell, counsel for defendant Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, then discussed Appellate Exhibit (AE) 118M, which ordered the commission to modify its information security infrastructure. He noted that a joint proposal had been developed that included a 60-day clock for defense classification review and kept the classification review function to the Defense Department’s Office of Special Security. However, Connell stated that this jointly proposed system was not functioning well in practice. Cohen agreed to accept a proposed order that would continue to monitor this system.

After a brief recess, Cohen then opened discussion on AE 523N, in which the defense sought the identity of a variety of witnesses, including CIA and medical witnesses, Camp VII witnesses with knowledge of policies in 2006 and 2007, and Bureau of Prisons witnesses who visited the CIA black sites. Connell stated that the government had not complied with the defense’s discovery requests regarding these witnesses.

Maj. Christopher Dykstra stated on behalf of the government that some information would be produced regarding particular witnesses but that the government had determined that other discovery requests should be denied. Cohen asked that the defense prepare arguments regarding outstanding witness identity disclosures for a future classified session.

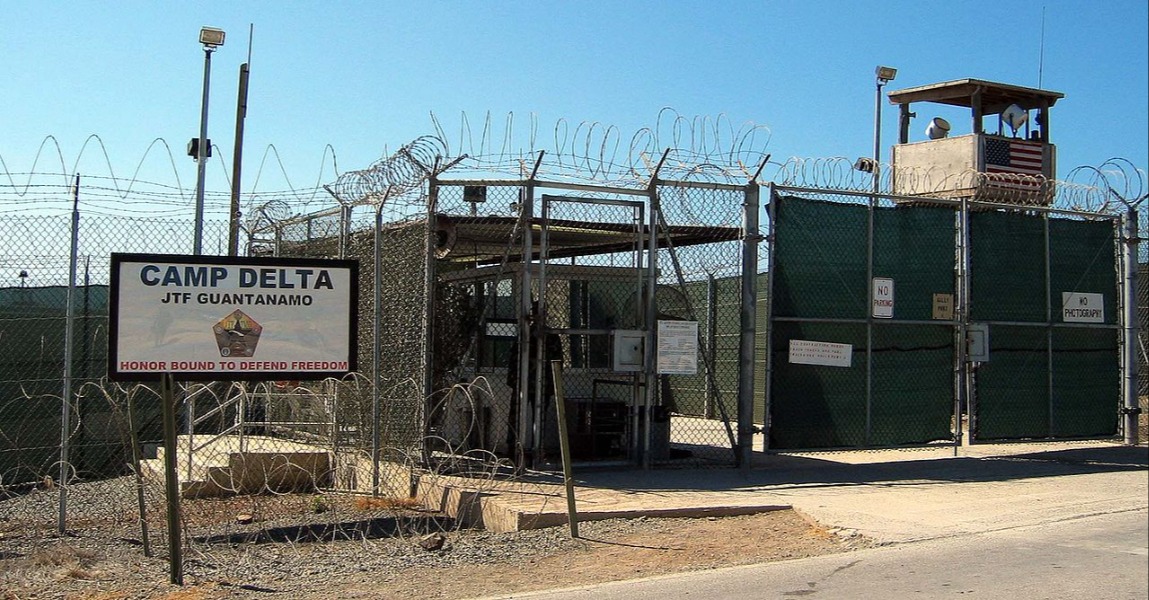

Next, Connell noted that AE 658, in which the government provided notice of classification guidance, also revealed previously unknown declassified information, including that Echo II (a facility at Guantanamo Bay) was a black site where defendants Mustafa al-Hawsawi, Ramzi Binalshibh, and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri were held and that FBI agents had been detailed to the CIA’s Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation (RDI) program. Connell stated that the new guidance usefully clarified the rules dictating what the defense can produce or elicit evidence on, but he added that these parameters seem unduly restrictive.

Connell proposed that any question that itself contains classified information should be asked in a closed session, and that any questions that might elicit classified information should be flagged in advance, permitting the government to invoke the classified information privilege if necessary. In response, Cohen reaffirmed his commitment to presiding over a fair trial and said that this issue would be discussed further in an 802 session.

Gary Sowards, counsel for Mohammad, then argued that the purpose of the government’s classification guidance is to “continue a government cover-up of what happened in the black sites[,]” particularly acts of torture, and that it effectively relegated the defendants to the position of mere spectators.

In response, Clay Trivett, on behalf of the government, stated that the guidance outlined in AE 658 was consistent with the government’s actions over the past seven years of litigation. Trivett also noted that the government was preparing a consolidated version of its previous classification guidance to provide to all parties for their use.

After recessing for lunch, the commission turned to discussion of AE 502 and AE 617. Citing interstate commerce jurisprudence, Connell argued that the military commission lacks personal jurisdiction over Ali due to a lack of hostilities. He cited Hamdan and Bahlul in support of this argument as well as differing rulings made by previous military judges regarding AE 502BBBB and AE617K that, Connell argued, call into question whether the commission can properly exercise jurisdiction over his client. Connell also cited the Tadic factors to argue that hostilities had not begun at the time of the events relevant to the proceedings.

Conversely, Trivett expressed frustration that the issue of hostilities was being raised again. He stated that the legislative history of the Military Commissions Act was clearly intended to grant the commission jurisdiction over the 9/11 attacks, among others. Additionally, he submitted that, even if there was a disagreement about whether hostilities existed as early as 1996, the 9/11 attacks themselves were sufficient to establish hostilities and trigger the law of war.

Cohen stated that he acknowledged the serious nature of the issues at hand and that he would make a determination based on the interest of justice. He then stated that the following day’s session would be closed, and the commission went into recess.

September 11

Judge Cohen called the public proceedings back to order two days later. Chief Prosecutor Brig. Gen. Mark Martins advised that family members of 9/11 victims would be present in the court’s gallery as it was the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. Cohen stressed that neither the significance of the day nor the individuals in the gallery would have any influence on his decision making.

Cohen discussed his decision to issue a trial date in this case. Cohen stressed that he thought the dates picked were consistent with the interests of justice, the needs of the parties, and his obligation to move the matter forward.

The commission then turned to several of the defendants’ joint motions for discovery of material related to a motion to suppress several of the defendants’ statements to the FBI during interrogations. Connell maintained that the government has not turned over evidence that shows when and how much information was shared between the FBI and CIA interrogators after 9/11. Connell asserted that the defense already had evidence that the FBI was participating in the RDI program as early as 2003 and that the documents sought in this discovery request support the argument that the FBI’s “clean team” knew about statements Ali made to interrogators when he was in CIA custody.

The commission then turned to a second discovery motion for documents that gave interrogators specific questions for the detainees and explained why those questions were important. Connell added that the withheld information requests were significant because they provide insight into how the government built its conspiracy case.

After a 15-minute recess, Rita Radostitz, counsel for Mohammad, argued that the fruit of the poisonous tree issues pointed out by Connell also affected other aspects of the case, like the defense’s motion to dismiss based on outrageous government conduct or a mitigation argument at sentencing. Denny LeBoeuf, counsel for Mohammad, then argued that there is a line of Supreme Court cases, starting with Brady v. Maryland, requiring the disclosure of this type of evidence, when it is not destroyed or unavailable.

Edward Ryan, replying for the government, argued that the evidence shows the defendants were proud to tell FBI agents they were responsible for 9/11 and that the government’s evidence starting from that point was not derived from torture. Ryan stressed that the government has disclosed almost all the information that the defense has asked for and that there is very little that supports the defense’s argument that the FBI “clean team” knew about the CIA interrogation’s questions and methods.

After the midday break, the commission heard the defense’s arguments for a discovery motion regarding the relationship of the prior convening authority, Christian Reismeier, with members of the prosecution team. William Montross, counsel for defendant Walid bin Attash, argued that capital cases demand due process and that it was essential under relevant case law that Reismeier be disinterested and not even appear partial. Yet Reismeier’s position on the issues of conspiracy doctrine and the laws of war were clearly stated in an amicus brief he had signed, meaning the defense would have to argue these issues in front of someone who had already taken a strong stand on them.

Trivett responded for the government that Reismeier had never hid his prior involvement in the military commissions and did not angle to be appointed convening authority before being recruited for the role. Trivett also stressed that the convening authority’s role is largely that of an executive and administrator, not a judge. Trivett argued that the defense mischaracterized relevant precedents, which required only that Reismeier not be “so closely connected to the offense that another reasonable person would conclude that Reismeier had personal interest in the matter.” Trivett concluded by adding that the defense’s discovery motion here is unnecessary because it already has all the evidence it needs to argue that the convening authority was partial.

After a midday break, the commission started to hear arguments on how the government should substitute and summarize classified material. Brig. Gen. Martins, for the prosecution, argued, first, that ex parte consideration of motions for substituted evidentiary foundations and associated protective orders were required; second, that the military judge should find that the evidence is reliable based on the specific circumstances surrounding its collection; and third, that, because the cross-examination of the foundational witnesses would have few constraints, it would provide the accused with substantially the same ability to make his defense as the disclosure of the specific classified information.

At this point the court halted its session for the day.

September 12

The next day, Judge Cohen reopened the morning session by instructing defense counsel to present argument on two issues: (a) whether the military judge has the authority to consider substituted evidentiary foundations for classified materials on an ex parte basis and (b) what criteria should be used to determine whether the substitutions are satisfactory, whether reviewed ex parte or otherwise.

For Mohammad, Sowards argued that the plain language of 10 U.S.C. § 949p-6(c)(2) and 10 U.S.C. § 949p-3 does not give the military judge the authority to consider classified substitutions ex parte. He further noted that these statutory provisions often address instances where the defense already has possession of the evidence the prosecution seeks to prevent from being disclosed or used at trial.

For Binalshibh, Maj. Virginia Bare clarified that 10 U.S.C. § 949p-4 governs discovery hearings, which can be held ex parte and for which the accused has no right of reconsideration. 10 U.S.C. § 949p-6 governs the procedure for introducing evidence in pretrial or trial proceedings, including substitutions for classified evidence. The latter only references “in camera hearings,” not “ex parte hearings,” and indicates that the accused can move for reconsideration, which is why the defense believes it is entitled to be included.

Cohen expressed his understanding that the prosecution had argued that the military judge was to take on the role of defense counsel during ex parte hearings on substituted evidentiary foundations. He noted the difficulty of trying to determine what five different defense teams may want to challenge with regard to any piece of evidence and ensuring a fair trial.

Connell admitted the classified discovery process in this commission has always allowed the prosecution to make ex parte submissions and that the defense sees the substitution only after the military commission authorizes it. Connell then discussed the other standards that come into play for substituted evidentiary foundations, namely, whether the evidence is otherwise admissible and whether the evidence is reliable.

Finally, Sean Gleason for the defense argued that Hamdan ruled that, in order to have a fair trial, the defense must be present at evidentiary hearings in order to have an opportunity to confront the evidence. The defense teams’ knowledge of the facts and evidence of this case far exceeds that of the military judge. Hence, the military judge is likely to be less effective at understanding what evidence might be helpful to the defense.

Cohen then recessed the commission until the afternoon closed session.

September 16

Judge Cohen called the proceedings back to order a few days later. He summarized the results of the R.M.C. 802 conference held the evening of Sept. 12 and morning of Sept. 13, including his order, AE 661, outlining the process for objections, especially as they pertain to classified questions and answers.

After covering matters concerning the exclusion of witnesses from the proceedings of the commission, the government called its first witness: FBI Special Agent James M. Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald relayed his history as an agent working the 9/11 case. He identified defendant Ali in the courtroom and said he became a person of interest around September 2001 based on evidence that included wire transfers, IDs and a post office box linked to Ali.

Fitzgerald also discussed a money transfer from “Isam Mansour,” an alias of Ali’s, to Marwan al-Shehhi, the latter a hijacker aboard United Airlines Flight 175. This account was shared with Mohamed Atta, a hijacker on American Airlines Flight 11. The document detailing the transfer was also linked to Ali’s post office box, and Ali’s fingerprints were on the original copy of the document.

Fitzgerald then went through numerous documents, including money transfers and passports, detailing al-Shehhi’s and Atta’s location and flight training in Florida and New York as well as how Ali connected to those transfers.

The testimony then turned to Fitzgerald’s access to information originating from when Ali was in CIA custody. While he wasn’t aware of any information from CIA interrogations that helped the FBI obtain evidence, Fitzgerald did have an opportunity to interview Ali. He then went on to explain the environment of that interview, relevant FBI guidelines and the rights advisement he gave to Ali.

Fitzgerald went on to detail the substantive part of his interview with Ali, who recognized several documents with his handwritten notes and fingerprints that were in an apartment associated with al-Hawsawi. Ali would later confirm multiple documents of cash transfers to the Shehhi and Atta joint account. Fitzgerald then explained Ali’s answers relating to his uncle Mohammad and his role in al-Qaeda. Ali mentioned Mohammad advised him to assist al-Shehhi. Fitzgerald also recalled Ali stating he purchased a flight simulator and a flight deck video with al-Shehhi.

Ali also sent money to Nawaf al-Hazmi, a hijacker on American Airlines Flight 77. Fitzgerald noted that Ali confirmed his own ID, which corroborated much of the information in the multiple cash transfers and visa application previously discussed. Ali had admitted that “Isam Mansour” was an alias he used to protect his identity when transferring money.

Ali also knew Hani Hanjour, a hijacker on Flight 77, and opened a bank account with him while in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In the interview, Ali confirmed a deposit made to open the account. After relaying Ali’s comments on how he helped those transiting from the UAE to the United States, Fitzgerald remarked that Ali recognized a photo as being either Wael or Walid al-Shehri. From a photograph presented during the interview, Ali could not tell if it was Walid or his brother Wael. Later in that interview, Fitzgerald presented a photo of Wael al-Sheri, and Ali again could not tell the difference among the brothers. Both were 9/11 hijackers.

While Fitzgerald suspected that Ali would have met another hijacker—Satam al-Suqami—he did not press Ali when he said he did not recognize a photo of al-Suqami since he was wearing American clothes and had a short haircut. However, Ali did recognize pictures of Majed Moqed, Ahmed al-Ghamdi, Mohand al-Shehri, Ahmad al-Na’mi, Hamza al-Ghamdi, and Ahmad al-Haznawi, all 9/11 hijackers. Ali said he helped most of these men to transit through the UAE.

Fitzgerald also mentioned that Ali identified al-Hawsawi, who was sent by Mohammad to assist Ali in transiting people through the UAE. Ali also knew Binalshibh was planning on going with the others to the United States but was unable to obtain a visa.

Ali left the UAE on Sept. 10, 2001, for Pakistan, where he was joined by Binalshibh, Mohammad, and al-Hawsawi. There, Ali watched the events of 9/11 on television and Mohammad confirmed it was the people he transited through the UAE who caused the attacks.

The commission subsequently closed the proceedings for the day.

September 17

Judge Cohen called the proceedings back to order the next day. Jeffrey Groharing, counsel for the government, resumed direct examination of Fitzgerald, playing a video, AE 628AA Attachment ZZZ, though the defense disputes its authenticity. Fitzgerald identified the various hijackers in the video and confirmed that the kunyas (nom dé guerres) used in the video were consistent with those Ali identified.

Groharing showed Fitzgerald AE 628AA Attachment P, a sketch Ali made to illustrate different roles held by al-Qaeda members. Fitzgerald explained that the top level was the planner who organized an operation, the middle level was the facilitator who would handle the logistics of the operation, and the bottom level consisted of operatives. Ali had identified Khalid Shaikh Mohammad as a “planner” and Osama bin Laden as a “leader” at the top of the document.

Below those names, Ali had identified Binalshibh as a facilitator who worked with Marwan al-Shehhi; Mohamed Atta was “a mid-level leader/facilitator” in the United States; Ali himself was a facilitator, as was al-Hawsawi. Below those individuals were hijackers Ziad Jarrah, Marwan al-Shehhi, and Hani Hanjour. The purpose of different roles was security.

Next, Fitzgerald testified that Ali stated that the purpose of the 9/11 attacks was “to express discontent … or opposition to U.S. support of Israel.” Ali stated that the priority was to attack political or military targets. Groharing asked Fitzgerald to read statements and describe a video articulating al-Qaeda’s ideology and to read from “The Islamic Response,” a document the accused filed pro se in 2009. Fitzgerald confirmed that this ideology was consistent with the justifications Ali had provided.

After a 15-minute recess, Groharing asked Fitzgerald to read transcripts of conversations Ali had with “G” and “F,” Faraj al-Labi. In conversations with G, Ali stated that he left the UAE on Sept. 10 because the company he worked for was shut down and the government cancelled his residency. Ali then stated that when he told this story to the CIA, the agent said he believed him but the American people would not.

When Groharing had asked Fitzgerald to read a Detainee Election Form from Ali’s Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT), the court clarified that the government would call Judge DeLury to testify about this document and other CSRT records.

After the midday break, Connell began his cross-examination of Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald clarified that he initially became one of the case agents for the PENTTBOM team, the FBI’s codename for the 9/11 investigation, “specifically for the prosecution of Zacarias Moussaoui.” Fitzgerald discussed a request to a CIA employee to find out when he had access to a closed network, operational around 2006-2007 and now defunct, that he used to make requests.

Connell then turned to questions regarding the FBI’s organization and record-keeping, noting that he was most interested in the period between 2001 and 2007. Connell inquired about the information workflow of the Automated Case Support (ACS) system and asked how many 302s were produced to or withheld from the defense during discovery in the Moussaoui case.

Connell then asked about pre- and post-9/11 information-sharing among agencies. Post-9/11, there was an emphasis “on sharing information to prevent another attack” and a mandate of information-sharing between the FBI and CIA under the Homeland Security Act of 2002. Fitzgerald responded that he was aware of the act “in broad terms.”

Connell then discussed CIA members staffed with the FBI and Fitzgerald’s access to various agency systems. Fitzgerald stated that between 2001 and 2007 he had access to “intelligence products produced by other agencies.” Fitzgerald stated that in Binalshibh’s case, he had regular access early on, in late 2002, to debriefings, but then “that changed” and he no longer had access to CIA cables.

Fitzgerald clarified his testimony from Dec. 7, 2017, explaining that he did not later have access to information through classified channels about al-Hawsawi or Ali, he only had “sporadic access,” and some of his co-workers had access to some of the CIA detainee reporting.

Connell moved to Fitzgerald’s personal record-keeping, asking about handwritten notes and emails. He then asked about the investigation of the attack on the USS Cole, but Judge Cohen halted the line of questioning because of an earlier ruling, permitting only questions concerning a video regarding the attack. Fitzgerald was then excused.

Connell argued that, pursuant to a prior trial conduct order regarding statements defined by R.M.C. 914, the government had not complied in producing all of Fitzgerald’s handwritten notes and emails. Trivett responded that the scope of the government’s obligations was not as broad as Connell maintained and addressed steps the government had taken to comply. Cohen stated that he was not ready to rule and would first prefer to hear questioning regarding correspondence with the CIA “or people who had access to any statements gleaned from the RDI program” and how those were used in the questioning of Ali before issuing an appropriate remedy.

After a 10-minute recess, Connell resumed cross-examination regarding the mobilization of the FBI in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, interviews Fitzgerald conducted and the organization of the investigation. Fitzgerald stated that the PENTTBOM team assembled around October 2001.

The commission then closed proceedings for the day.

September 18

Judge Cohen started the proceedings and Connell continued the defense’s cross-examination of Fitzgerald. Connell started by focusing on how Fitzgerald and his colleagues assigned to the PENTTBOM team and the High-Value Detainee Prosecution Task Force (HVD team) would share information pertinent to their cases. Fitzgerald stated that he and other FBI agents had access to information from the wider intelligence community about the detainees he interviewed. Fitzgerald also stated that individuals from the CIA, Department of Defense and National Security Agency were all assigned to the HVD team and that, prior to his trip to Guantanamo, the CIA briefed him on the enhanced interrogation techniques used on these individuals.

Connell then asked Fitzgerald about his first investigative assignment immediately following 9/11. When Fitzgerald had memory gaps about these assignments, Connell stated that the defense did not have access to a series of FBI reports that might have helped Fitzgerald remember.

After Groharing objected to a line of questioning regarding the investigation, Connell emphasized that the CIA detainee reporting was “a critical part” of the investigation and that the FBI and CIA had worked together. Groharing responded that any materials gathered before Ali’s capture were irrelevant.

Cohen noted that the court had already concluded that the scope of questioning would include issues of taint and derivative evidence, but he provided guidance to Connell that he should determine the depth of inquiry needed before discussing issues not directly related to his client.

Connell resumed cross-examination on the raid of al-Hawsawi’s apartment in June 2002, since Fitzgerald used some of the seized items in his interview with Ali. A foreign government had provided information as a result of the search, and Fitzgerald later found a witness to interview regarding the seized items. Connell noted that it would be difficult for defense counsel to find this witness due to the invocation of national security privilege. Connell then addressed documents that were shown to Ali but that the FBI had not found in its search.

Fitzgerald then relayed he was on temporary duty in Washington, D.C., or Virginia in September 2002, likely preparing for the prosecution of Moussaoui. He worked at Guantanamo as part of the PENTTBOM team focused mainly on Muhammad al-Qahtani. However, he could not interrogate him until November 2002, a month after arriving at Guantanamo, since the Defense Department had exclusive custody.

Fitzgerald then reviewed a 2002 request he had made for the CIA to ask questions of al-Hawsawi about al-Qahtani. However, Fitzgerald testified that he didn’t recall if he received answers back from the CIA.

Connell continued with his cross-examination, turning to AE 628GG, a CIA cable concerning custodial interviews of al-Hawsawi in early 2003. Based on the cable, Fitzgerald confirmed that al-Hawsawi had identified al-Qahtani. The cable also relayed that al-Hawsawi claimed that al-Qahtani traveled alone to the United States, of which al-Hawsawi had been informed by Mukhtar and Binalshibh. Connell presented AE 628PP, a message from the PENTTBOM team to the CIA. Fitzgerald confirmed its contents; the PENTTBOM team sought both to pass questions for the CIA to ask al-Hawsawi and physical access to al-Hawsawi themselves.

During the course of the Moussaoui litigation, the Fourth Circuit noted that the prosecution and the PENTTBOM team received the same reports that had been distributed to the intelligence community concerning Massaoui. As a result, substitutions were created for the testimony of witnesses, who were being held at Guantanamo, including al-Hawsawi, Binalshibh, and Mohammad. Fitzgerald stated that the substitutions likely came from CIA cables and Cohen confirmed that he would review the substitutions and the cables to confirm their similarities.

Fitzgerald then confirmed that he was the drafter of a request to the CIA for fingerprints from Ali. He stated that he had no knowledge of or reason to believe that prior fingerprints from Ali had been taken or submitted to the FBI, and he testified that the CIA had never responded to his request for fingerprints.

After a short recess, Connell resumed cross-examination of Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald confirmed that he presented a picture of a CityBird video box to Ali during the course of an interrogation. Connell then asked Fitzgerald about a variety of questions he had asked Ali, including about the credit card statement reflecting charges for a flight simulator and additional money transfers.

Fitzgerald then testified that the FBI requested the interrogation of Binalshibh and asked for CIA information in return. Fitzgerald also confirmed that the FBI sent a message to the CIA providing questions for Mohammad, Bin Attash, Binalshibh, and several other prisoners held at Guantanamo. However, Fitzgerald also stated that he did not know why the FBI would have to ask the CIA to question a Guantanamo prisoner.

Finally, Connell questioned Fitzgerald about information sharing between the FBI and CIA regarding money transfers, including additional questions submitted by the FBI to the CIA to be put to Ali regarding such transfers.

The session then recessed. Cohen confirmed that the following day’s session would be open in the morning and closed in the afternoon.

September 19

Cohen opened the proceedings by taking attendance with Connell resuming his questioning of Fitzgerald.

Connell presented Fitzgerald with a series of financial documents that Fitzgerald used in his interrogation of Ali, including receipts from the UAE Exchange Centre and Wall Street Exchange Centre for various sums, a printout for the rental of a post office box, and bank records. Other materials included a copy of Ali’s passport, his curriculum vitae and his immigration records (in Arabic). Fitzgerald confirmed that the United States had asserted national security privilege over the origin of each of these documents and that these documents were the foundation for the financial presentation he gave in his direct examination on Sept. 16.

Connell next turned to a series of CIA cables from between 2003 and 2006 that discussed what Ali had said over the course of interrogations at the black sites prior to Ali’s transfer to Guantanamo. Fitzgerald confirmed that these cables reflect information that he had elicited during a subsequent four days of interrogation at Camp Echo (at Guantanamo Bay, in January 2007), including information about Ali’s relationship with Ahmad al-Kuwaiti and al-Hawsawi, Ali’s answers under CIA interrogation regarding separate post office boxes, and his visits to Pakistan, among other details.

Fitzgerald stated that he was not sure whether he had interrogated Ali on any topics that the CIA had not previously interrogated him on. After a short recess, Connell resumed his cross-examination of Fitzgerald. Connell began by questioning Fitzgerald about an “Organizational Message Form”—an internal FBI communication that is then sent to the CIA—seeking information about “Individual K,” who was believed to have introduced Ali to the Dubai Islamic Bank. Connell noted that the document included a series of questions regarding Individual K and his association with al-Qaeda. He then introduced a second document including questions proposed by the FBI for use during CIA interrogations of Mohammad, Ali, al-Hawsawi, and Binalshibh.

Groharing objected to Connell’s reading of the questions on the grounds that the information they revealed was “cumulative,” to which Connell replied that he was seeking to show the coextensive interrogation or cooperation between the FBI and CIA, which the government had not yet acknowledged. After some debate about whether the questions could be publicly filed in an unclassified manner, Connell proceeded in reading the questions drafted by Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald confirmed that he knew the questions would be posed to the defendants by the CIA. He then confirmed that he knew the approach to be utilized by the CIA was not a “law enforcement approach” and that the CIA interrogators were not likely to ask the detainees for information “nicely.” Fitzgerald also stated that it was his understanding that the CIA did not favorably receive the questions, though he was not certain why.

Connell then questioned Fitzgerald about his interrogation of Ali regarding the “shoe bombers” (regarding further FBI and CIA coordination on this topic) and alleged U.S. government surveillance in Malaysia in 2001. Connell focused his questions on the interview reports (302s) produced by one of Fitzgerald’s FBI colleagues on the PENTTBOM team that included information elicited during interviews at the black sites and Guantanamo. Fitzgerald stated that it was likely that his colleague had access to the CIA cables discussed earlier and that the colleague had passed questions to the CIA for them to pose to defendant Bin Attash.

After a lunch break, Connell restarted his cross-examination of Fitzgerald, asking him about Mushabab al-Hamlan, an associate of Flight 93 hijacker Ahmed al-Nami. Connell highlighted that Fitzgerald requested that al-Nami be interviewed by a foreign government using questions prepared by the PENTTBOM team and that Fitzgerald also provided questions and a photo of al-Nami to CIA interrogators knowing they would ask several of the defendants.

Connell then discussed how the information in the 2003 CIA cable appeared to be replicated in an FBI report. Connell asked if Fitzgerald believed the FBI agent who wrote the FBI report “likely” was able to give intelligence requests to the CIA.

Connell then turned the conversation to the process Fitzgerald used to request information from the CIA. Fitzgerald stated that receiving answers (at his classification level) was rare and he could not recall a specific CIA cable he had seen during the cross-examination that might have been in response to one of his requests. Fitzgerald was unable to determine if there was one place that had records of the classified information he did review because the process at that time was so ad hoc.

Connell then asked Fitzgerald about his access to the database in the High-Value Detainee (HVD) system. Fitzgerald said he did not recall ever failing to receive a document that he requested from the system but it was possible that he did have restricted access on the HVD closed network.

Connell also asked Fitzgerald about his relationship to the investigation of an individual on the defense team who had allegedly leaked classified documents. Fitzgerald stressed that as soon as he learned about the case and was asked to assist, he refused and informed the person who informed him not to discuss it any further.

As a result of further prompting from Connell, Fitzgerald discussed his briefing on CIA procedures at Guantanamo Bay and a meeting where he was informed he would get to interview the detainees. After a break, Connell confirmed that Fitzgerald knew the detainees had been previously interviewed, and potentially tortured, by the CIA at the facility he was going to use to “reinterview” them. Fitzgerald informed the commission that during his interview with al-Hawsawi he recalled the defendant stating that he had been in that room before, insinuating his torture at that location, and Fitzgerald did not ask a follow-up question. Fitzgerald stated that he did not ask about al-Hawsawi’s CIA detention because the FBI-led team wanted to get answers relevant to their investigation and not rattle him.

Connell then asked Fitzgerald to describe the detention facility where he interviewed al-Hawsawi, identify individuals present for the interrogation and confirm that he did not provide al-Hawsawi with a Miranda warning. Fitzgerald did all of this. Connelly stressed that, despite al-Hawsawi having an appointed defense team at that point, which Fitzgerald knew about, Fitzgerald did not inform al-Hawsawi that the statements he made could be used against him in court.

At this point the commission began a recess followed by a closed session.

September 20

Cohen called the proceedings to order again the next afternoon, after a closed session in the morning. Fitzgerald came back on the witness stand and Groharing began redirect.

Fitzgerald discussed his interrogation of Ali, noting how he would have Ali sign documents he recognized and that he asked Ali both open- and closed-ended questions. However, he did not recall using any statement from the RDI program when questioning Ali.

He then went over his prior testimony on his list of questions sent to the CIA, which covered the hijackers’ movements in the United States. Fitzgerald was attempting to fill intelligence gaps that might help to prevent another attack as well as find those who assisted the hijackers.

After a brief recess, Abigail Perkins, a former FBI special agent, took the stand.

After establishing that she was a member of the PENTTBOM team, Connell went on to ask about her work in the investigation of the East Africa embassy bombing case. She recalled her time investigating the Tanzania portion as a case agent, overseeing evidence collection, interviews and strategy. Connell then asked about her questioning of Khalfan Khamis Mohamed. She replied that she read him his rights multiple times, to include a full Miranda reading while he flew to the United States in U.S. custody.

Connell then turned to her work as an agent in the aftermath of 9/11. She listed some of the members of the PENTTBOM team as well as her specific section of focus: financial and overseas issues, particularly in the Middle East. She then talked about how they would receive information from other agencies. These usually included either FBI analysts who collected interagency information or a CIA liaison.

Connell then asked about the Tariq Road raids. Perkins recalled her review of documents in Karachi that were recovered with the capture of Binalshibh. However, she only had a short time there and was able to review them further in Islamabad.

Asked about the capture of al-Hawsawi, Perkins remarked that she knew of his capture within a few days (along with that of Mohammad). She recalled exploiting information that was taken from the site of the capture. She then reviewed a past request to the CIA asking to access al-Hawsawi, but she didn’t remember getting a response.

Perkins discussed the process of gathering photographs from the site exploitation and sending them for presentation to the high-value detainees, to see if they could identify or give information about the individuals appearing in the photographs.

Connell then discussed Faruq al-Najdi and his alias Saud al-Rasheed with Perkins. During the questioning of Ali, she showed him a photograph of al-Rasheed. When she questioned al-Hawsawi, she asked about the “little blue notebook” that had been found during the site exploitation of his capture, which appeared to have a ledger of payment amounts. One of the names was associated with al-Najdi, and Ali stated that he had transited through Dubai and then was never heard from again.

Connell next addressed efforts made to determine whether al-Najdi was al-Rasheed’s alias through requests from the FBI to the CIA for the questioning of Mohammad and al-Hawsawi. After a 15-minute recess, Connell also asked about CIA cables regarding interrogations of al-Hawsawi, Binalshibh, and Mohammad, with information about questioning regarding al-Najdi/al-Rasheed and the little blue notebook.

Connell then turned to Perkins’s assignment to question al-Hawsawi and/or Ali and attachment to the HVD team. Perkins discussed “buckets” for each detainee on a computer system, which contained CIA reporting about or from a detainee. Perkins recalled that she was involved in four interviews: Ali, al-Hawsawi, Ghailani, and Gouled. She stated that Fitzgerald was the primary agent on Ali, while she took the lead on the other three interviews.

Connell also asked about the hard-copy “stacks” available for Perkins’s review, which contained printed-out documents from a computer picked up during a capture of an individual.

Groharing, trial counsel for the government, then began cross-examination.

Groharing asked if the purpose of the interview with Ali was “to obtain a usable law enforcement statement completely detached from any statement that he had made in CIA custody or any evidence that could have been derived from any statements that he had made,” and Perkins stated that was accurate. Perkins said the interview was “document based,” meaning she relied heavily on documents. Perkins stated her interaction with CIA personnel was limited to CIA attorneys who were reviewing documents she wanted to use in the interviews to protect national security equities. The only documents used in the interview were those for which the FBI was responsible.

Turning to the interview with Ali, Perkins stated it was “rapport-based.” She said Ali did not seem to have difficulty understanding the agents and appeared relaxed, and the interview was “cordial.” She did not ask him about how he had been treated in CIA custody, because it would have required CIA permission and they were attempting to draw a line between the CIA and FBI. She also stated that this would not have served the rapport-based approach.

Perkins further explained why she thought that the interview was voluntary. The agents established that Ali could speak English and ensured that he knew that they were from the FBI, not the CIA, and that he was no longer in CIA custody. They informed Ali that he could take breaks, and during the course of the interview they would ensure that he was still willing to speak to them. Ali acknowledged that this investigation was different from the CIA’s. He also wrote a note asking to meet with the agents to share more information. Perkins stated she thought his statements were reliable and were consistent with the PENTTBOM investigation.

At this point the commission began a recess followed by another closed session.

September 23

Proceedings resumed a few days later. Connell, counsel for Ali, began by outlining the order of witnesses for the day’s proceedings: FBI Special Agent Stephen McClain, Judge Bernard DeLury, D.J. Fife, and possibly the Camp VII commander.

Connell proceeded to question McClain about his assignment as a special agent with the Criminal Investigative Task Force (CITF) from 2006 to 2016, which was a joint task force assigned to investigate crimes that occurred around the events of the 9/11 attacks. CITF had military and civilian members from the military branches’ criminal investigation units. McClain explained that CITF-GITMO had investigative responsibilities over the people detained at Guantanamo Bay. McClain had worked on the CITF team charged with investigating alleged bodyguards of Osama bin Laden.

In August 2007, McClain was also assigned to the HVD team. Connell attempted to elicit testimony that the CIA had selected McClain for the HVD team, but McClain clarified that he never said the CIA had played a role in his selection, that the FBI led the team and that he was unaware of anyone on the team being from the CIA.

Specifically, McClain was selected for the Ali interrogation team. He explained that he did not gain access to closed network information about Ali until after the first interview in January 2007 and was deliberately not given information about the detainees prior to their transfer to Guantanamo. McClain had no prior knowledge of Ali’s treatment or statements made in CIA custody. McClain confirmed that Ali was advised that he did not have to speak with the HVD team agents interviewing him and that he could end the interview at any time.

Connell walked McClain through two trips McClain made, one in July 2012 to Guantanamo and another in January 2013 to FBI headquarters, to collect evidence and chain of custody documentation. McClain confirmed that a regular process of evidence transportation by CITF agents was not established until after these two trips, but once established, the evidence transportation would occur every quarter and CITF agents would create chain of custody documentation.

Groharing for the prosecution conducted the cross-examination of McClain. McClain affirmed that the purpose of interviewing Ali was to obtain a usable law enforcement statement, unconnected from any statement Ali had made to the CIA or any evidence that had been derived from statements to the CIA. No one, including Special Agents Fitzgerald and Perkins, discussed statements Ali had made to the CIA with McClain prior to the interview he conducted with Ali.

Groharing asked if it would be fair to characterize the CIA’s role in the interviews conducted at Guantanamo as ensuring that the agents conducting the interviews had appropriate security clearances and that the CIA did not play a substantive role in determining what questions were asked of Ali. McClain confirmed this.

McClain described Ali as having a very good rapport with Fitzgerald and Perkins in the interviews and that Ali was relaxed and open to talking about anything. McClain detailed the accommodations offered to Ali throughout the interviews, including breaks, food and drinks, and advisements that he could end the interviews at any time. Ali was never threatened, nor did he appear confused or disoriented at any time during the interviews, and McClain expressed his belief that the interviews were voluntary.

On redirect from Connell, McClain emphasized that the lawyers working with the HVD team ensured that the agents conducting the detainee interviews at Guantanamo had no prior knowledge of the detainees from their time in CIA custody.

The commission then recessed to transition to a closed session so that McClain could be questioned about classified matters.

September 24

Cohen reopened proceedings the next day by recapping the previous day’s closed 505(h) session and R.M.C. 806 classified testimony.

The prosecution then called Judge Bernard E. DeLury, a superior court judge in New Jersey, to testify as a witness. DeLury recounted his professional background as a Navy judge advocate general, serving as a criminal defense attorney, prosecutor and military judge.

In 2004 and 2007, DeLury served as a member of the Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) for Guantanamo Bay. The CSRT was tasked with determining the enemy combatant status of Guantanamo detainees. Detainees and their military-appointed personal representatives were present at CSRT hearings; both the government and the defense were given the ability to present evidence and call witnesses even though they were administrative, fact-finding proceedings.

DeLury confirmed that he was unaware of any FBI or other law enforcement reports concerning the detainees whose tribunals he presided over, including seven high-value detainees, five of whom are the co-defendants in this case. Ryan, for the prosecution, walked DeLury through the transcript of Mohammad’s CSRT, including Mohammad’s understanding of the proceedings and his affirmative statements to the tribunal that he swore allegiance to Osama bin Laden and that he was the operational director of the 9/11 attacks. DeLury stated that he believed Mohammad understood what was happening and that he made the statements voluntarily and was not under mental or physical duress. Regarding Bin Attash and al-Hawsawi, DeLury similarly confirmed the accused’s understanding of the tribunal proceedings and that their answers were voluntary and not given under mental or physical duress.

DeLury stated that Ali appeared to understand and speak English. DeLury discussed the ruling with respect to the request made through Ali’s personal representative to produce several witnesses who were also detainees at Guantanamo—he ruled that the personal representative would provide a list of questions to witnesses.

DeLury stated that Ali gave a “general denial” during the CSRT panel members’ questioning. DeLury stated that two statements from Ali and multiple statements from co-detainee witnesses were presented during the CSRT. Ryan noted that Ali had claimed “learned helplessness” and DeLury responded that Ali did not appear “helpless.”

After a lunch recess, Alka Pradhan, counsel for Ali, began cross-examination. Throughout, she referenced statements DeLury made during an oral history interview in 2015 to the Atlantic County Veterans History Project, AE 628BBB Attachment UU.

Pradhan first asked about DeLury’s background, JAG experience and training before his CSRT appointment. She also asked when DeLury first became aware that the United States was at war with al-Qaeda, but Ryan, for the prosecution, objected that this was beyond the scope. Cohen permitted Pradhan to ask about DeLury’s opinion of Ali once he was president of the CSRT, which she said she would return to.

Pradhan then discussed DeLury’s actions on and after 9/11 and the information he had access to before the CSRT. DeLury stated that he only had the information from the classified summary provided to him.

She then turned to the early CSRTs in 2004. After an objection, Cohen suggested that Pradhan rephrase her questioning to ask whether it was true that the CSRTs occurred more than two years after the detainees were taken off the battlefield. DeLury stated that would be his understanding based on public information.

Pradhan asked DeLury whether he was aware that the high-value detainees were held at black sites by the CIA prior to being brought to Guantanamo. DeLury did not know.

She then moved on to the 2007 CSRTs. DeLury described a paper by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) with an overview of the program and fact sheets on each of the 14 detainees. Pradhan introduced this document, titled “Summary of the High-Value Detainee Program,” as AE 628KKK Attachment AAA. Cohen ruled that Pradhan could ask questions regarding the conditions of Ali’s confinement and factors he considered in determining the voluntariness of statements.

DeLury agreed that he had an overview of the CIA detention program as provided in the overview section of the ODNI document, and that he knew by about December 2006 that Ali had been held in CIA detention.

Pradhan continued asking DeLury about his work on the CSRT. Of note was Pradhan attempting to confirm that DeLury didn’t find the FBI investigative summary persuasive. This drew an objection from the government as beyond the scope of their direct questioning. Pradhan went on to explain that this line of questioning was geared toward determining what information was provided to the CSRT and how both the FBI’s and the CIA’s evidence was integrated and used to determine Ali’s enemy combatant status. Connell also submitted a written, classified response to the government’s objection.

The government’s response was argued orally. They argued that they did not intend to introduce Ali’s CSRT transcript in their case against him, which removes the issue of the derivative evidence rule and makes any linkages between the RDI program and the CSRT process irrelevant. After additional arguments from both sides, Cohen permitted the defense to continue their questioning of DeLury but noted that he may address the objection later.

Pradhan then went into witness relevancy of the CRST. Due to objections from the government, however, she was not able to get into deliberative processes, which were found to be outside the scope.

Sowards, counsel for Mohammad, then opened his line of questioning. After laying the groundwork for DeLury’s competency on voluntariness and Miranda rights, Sowards went into the facts and circumstances surrounding Mohammad’s statements to the CSRT. DeLury replied that he would see it as concerning if he were reliably told of the torture of a defendant about whom he was making a voluntariness assessment. He also replied that the CSRT did not use Miranda warnings as such but did advise the accused that they had the right not to testify.

DeLury went on to review claims of mistreatment by Mohammad but noted that he felt no compulsion to examine them further at the CRST. He did recommend an investigation into Mohammad’s allegations of torture but did not receive a response before completing the CSRT’s final report. Sowards closed his questioning by asking about DeLury’s training in recognizing torture and other psychological conditions. DeLury replied he had none.

Pradhan briefly recrossed and, after reviewing the next day’s schedule, Cohen recessed for the evening.

September 25

The next day, counsel for the government Ryan started the day with a direct examination of D.J. Fife, an FBI fingerprint analysis expert and lab employee who has been with the FBI for 15 years. Fife was qualified as an expert without objection from the defense. Fife then discussed how he collected fingerprints from the defendants in 2008 and analyzed all the fingerprint documents entered into evidence, including fingerprint cards taken before he was assigned to the case. Fife then testified as to which documents belonged to which defendants.

After a break, Capt. Mark Andreu, counsel for Ali, began questioning Fife. Andreu questioned Fife about his training, experience and FBI procedures, especially as they related to creating a fingerprint document and maintaining its chain of custody. During this conversation Fife noted that he had met with the prosecution two times before his testimony and had refused to meet with the defense.

Andreu focused on the fact that each fingerprint analysis was based on the individual lab technician’s view of each print’s similarity. Fife detailed the way that analysts tracked their work so that others could see what parts of the fingerprint they used to match it. Fife also discussed the work he did in 2007 to verify the work of other analysts conducted in 2002. Fife also stated that the origin of a certain group of these documents, including the chain of custody from when some defendants were captured, was protected via the national security privilege.

Andreu asked Fife to discuss the FBI’s fingerprint cards for Ali and asked where the FBI had gotten its fingerprint cards for Ali before Andreu conducted his in-person analysis in 2008. Fife stated that all the print cards have a date that notes when the prints were collected, but these cards do not note the days the FBI received those cards. Fife added that the fingerprint cards come to the FBI in a variety of ways, several of which are classified. Fife added that, with 25 different fingerprint cards, there are many ways to analyze the data so, normally, in this situation the analyst would ask for the most recent fingerprint card. But in this case the FBI wanted everything each agency had. Andreu concluded his unclassified cross-examination here.

The commission then moved to oral argument on the order of witnesses. Connell, counsel for Ali, discussed the logistics of grouping witnesses to order their testimony including a motion to compel former FBI Special Agent Aaron Zebley to testify because the government has not agreed to produce him. Connell stressed that Zebley was a central coordinator around the flow of information between the CIA and the FBI. Connell added that Zebley’s extensive experience in Karachi was tied much more closely to the ultimate issues before the commission.

Connell then suggested allowing the February witnesses to conduct deposition-style interviews in the D.C. area for less important witnesses and play tapes/segments for the court. Connell added that, when it came to the sentencing portion of the case, he would certainly prefer to play some video footage of earlier testimony without having to have witnesses return. Radostitz, counsel for Mohammad, said the defense was split on this issue because they would want to be able to make an argument for Mohammad’s presence at any deposition.

Connell then turned to discovery. He stated that his two problems were that the government’s discovery practice had come unmoored from the rules and that the legal environment had changed while the discovery methods remained static.

To support his first point, Connell pointed to the fact that only 13,000 302s, or FBI reports, had been provided to the defense, and the defense estimates that there are 165,000 total. Connell further noted that several of the redactions on the FBI’s reports do not appear to be for relevance but rather were hiding certain evidence of enhanced interrogation and other methods the CIA used on detainees.

Ryan stated that, given Connell’s arguments, the government would produce Zebley and work with the defense to try to reach an agreement regarding many of the redacted documents. Ryan also stated that rather than doing a deposition-style interview with certain witnesses, as suggested by Connell, the government would prefer live testimony via closed-circuit television.

Sowards, counsel for Mohammad, asked the court to consider minimizing the number of days witnesses who tortured the defendants would testify. He argued that these witnesses’ presence might affect the defendants’ willingness to come to court or negatively impact their psychological state. Cohen said he would consider this and, after a scheduling discussion, concluded the open session.

September 26

Cohen opened the day’s session per usual before taking attendance and turning to AE 655, the prosecution’s request for a court order to compel defendant Ali to undergo a mental health examination.

Trivett, on behalf of the government, noted that Ali’s defense counsel had contested the admissibility of any statements obtained during interviews, alleging that they are the product of torture and are therefore involuntary and do not serve the interests of justice. Trivett acknowledged that Ali is entitled to contest the admissibility of his pretrial statements but added that, as a consequence, the defendant waives any privilege against self-incrimination when introducing expert testimony about his mental health.

Trivett cited a previous military judge’s order in the United States v. Omar Khadr, in which the judge ordered this kind of mental health examination. He noted that the testimony from the prosecution’s expert witnesses resulted in a decision not to suppress statements that Khadr claimed were the product of torture. Trivett also asked that Cohen consider the motion as a request for discovery and clarified that the government’s request is for an exam, though subsequent relief could be exclusion of relevant evidence.

Trivett also quoted Kansas v. Cheever, a U.S. Supreme Court case in which the court found that prosecutors in a criminal trial may present psychiatric evidence in rebuttal where a defense expert testifies that the defendant lacked the requisite mental state, on the basis that “any other rule would undermine the adversarial process, allowing a defendant to provide a jury through an expert proxy with a one-sided and potentially inaccurate view of his mental state at the time of his alleged crime.”

Connell, on behalf of the government, urged the court to take a rules-based approach to the question of how to handle mental health evidence. He also noted that the defense had fully complied with the prosecution’s discovery request regarding the previous mental health examination that had been conducted by Lt. Cmdr. David Hanrahan. Among other exam results turned over to the prosecution, Connell noted that an MRI test had been taken and the imagery provided to the government.

Addressing Trivett’s reference to Cheever, Connell stated that the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure at issue in that case are not directly applicable to the present situation and, further, that no court-martial has ever ordered a pretrial mental health evaluation in a death penalty case.

He also noted that the government has access to more than a dozen compelled mental health evaluations conducted in the black sites by psychologists, pointing to a series of declassified CIA cables in which psychologists noted that Ali was “still developing a sense of learned helplessness.” Connell also cited other cables in which psychologists said that Ali “became psychotic” after having his head smashed against the wall and reportedly heard someone in an adjacent cell being beaten, raped, and tortured to death, along with a baby. Ali also reported returning to his cell and finding a small coffin holding the dead baby. Connell noted that these were psychotic hallucinations and that a series of mental health evaluations were conducted shortly thereafter.

Connell stated that the examiners in six evaluations found that Ali was fabricating these hallucinations in order to avoid enhanced interrogation. He then pointed to the next six psychological assessments, in which evaluators suggested that Ali suffered from anxiety and ADHD and, eventually, Irlen syndrome and depression. Connell suggested that these evaluations were a “form of validating human experimentation” to determine the effects of long-term incommunicado detention.

Finally, Connell noted that more than 24 psychologists had evaluated Ali, and that the defendant had undergone more than 250 separate examinations in total, the results of which are all available to the prosecution.

After a short recess, the court turned to discussion of AE 639 and AE 653, in which the defense argued for the delay of the upcoming court deadlines (in advance of the 2021 trial date) on the basis of interests of justice and logistical considerations, including poor conditions at Guantanamo and ongoing discovery efforts.

Radostitz noted that the government had made decisions that led to torture in these cases and to these being capital cases. In particular, she stated that the defendants had offered to plead guilty to noncapital charges in 2008 but that the government had rejected the settlement. She closed her statement by reiterating that the government had chosen to hold these hearings on Guantanamo in a court that is not regularly constituted, resulting in some of the delays in proceedings and requiring modifications to the court’s proposed timeline. Other defense counsel echoed these comments.

Ryan, on behalf of the government, then responded, stating that he deeply disagreed with the defense’s statement that it was the choice of the U.S. government to “stand in this courtroom today.” Rather he stated that the choice that was made was by defendant Mohammad, who invented “a crime so horrible that it became an actual act of war in an illegal war.” He reiterated the prosecution’s commitment to keeping on schedule and urged Cohen to limit the defense lawyers’ arguments.

After a lunch recess, Radostitz briefly responded to Ryan’s comments, stating that the presumption of innocence, particularly in a capital trial, is the bedrock of the American judicial system. Ruiz also stated that it is not true that there is no trial date that the defense would agree to, but that no trial should proceed without the proper elements and preparation.

Finally, James Harrington, counsel for Ali, addressed ongoing concerns about Binalshibh’s health, noting that he had been subjected to noise and psychiatric experiments in the black sites and has reported similar symptoms at Guantanamo. Harrington referenced Judge James Pohl’s 2015 order directing camp staff not to harass the defendant or to use noises and vibrations, but stated that Binalshibh has said that watch commanders have ignored this order

Cohen confirmed that the 2015 order remains in effect. Trivett then said that there is no evidence that Binalshibh is being harassed by U.S. government personnel. He also noted that Binalshibh had stopped taking his previous psychotropic medication and refused to try a new drug. In response, Harrington stated that it is impossible to make a psychiatric diagnosis without knowing a person’s full history, particularly with regards to torture, but that no personnel at the camp are permitted to inquire into what happened to Binalshibh at the black sites.

After some discussion of scheduling and logistical matters, the three-week session was then recessed.

.jpg?sfvrsn=d5e57b75_5)