Is the U.S. Winning Its Campaign Against Huawei?

More countries are shifting their position towards the Chinese telecom’s 5G equipment. But attributing that to the Trump administration is a stretch.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Huawei has had a bad few months as far as the United States is concerned. On May 15, the Trump administration issued a new export control rule, going into effect in September, to stop the Chinese telecommunications company and its suppliers from using American technology to make semiconductors. On June 30, the Federal Communications Commission officially designated Huawei a national security threat. And Reuters reported on July 9 that the Trump administration is planning to finalize regulations to bar U.S. government agencies from buying goods or services from any company using Huawei products. The administration’s argument for this series of moves is that these tactics are necessary to respond to the national security threat posed by Huawei, because its 5G technology serves as a vector for the Chinese government to spy, collect data or even conduct cyber operations abroad.

Meanwhile, other democracies have taken action against Huawei as well. The U.K. government has banned Huawei, telling domestic network operators to rip out any and all Huawei equipment from their 5G systems by 2027. This reversed a January decision by the U.K. to allow Huawei 5G technology into, at most, 35 percent of the country’s networks—and only the non-core parts (though the precise meaning of “core” to different countries is somewhat unclear). Shortly thereafter, the Indian government reportedly told two state-run telecommunications companies not to use Chinese telecom equipment in their network upgrades. On July 22, Reuters reported that the French government is telling telecom operators that licenses for Huawei gear won’t be renewed upon expiration, which isn’t an outright ban but effectively institutes one—or at least strongly discourages firms from using its equipment.

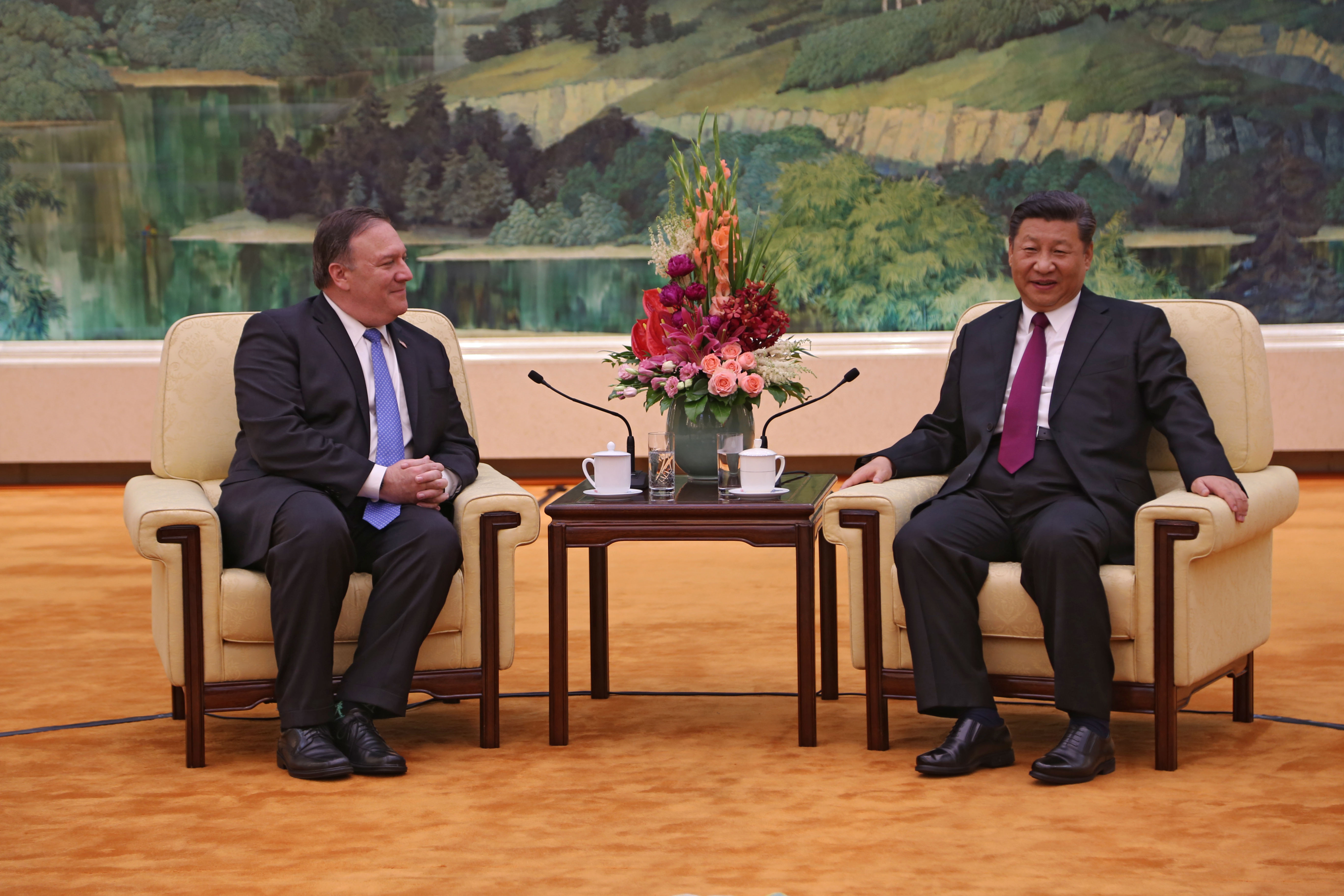

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asserts that “The tide is turning against Huawei as citizens around the world are waking up to the danger of the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance state.” The politics of Pompeo’s statement aside, is it really the case that the global tide is changing on Huawei’s 5G telecommunications technology? And is America’s long campaign to get Huawei banned around the world finally working?

Pompeo is probably right that Huawei is in a less advantageous position than it was a few months ago. But whether the U.S. can claim credit for this trend is a very different question.

Decisions coming out of some other countries in the past few months seem to indicate shifting positions on Huawei 5G technology, even if the announcements in question do not directly refer to Huawei. Denmark’s defense minister said in June that the country wants to be able to exclude 5G suppliers who aren’t incorporated in security-allied countries (the country’s biggest telecom did pick Ericsson over Huawei as a supplier last year). Also in June, Huawei lost ground in Singapore as major telecoms—including Singapore Telecommunications Company, which is majority-owned by a Singaporean government investment firm—chose Ericsson and Nokia over Huawei to supply sizable portions of the country’s 5G networks.

In some countries, actions on 5G have gone hand-in-hand with worsening relationships with China. In the U.K., officials were pursuing a multilateral democratic coalition on 5G alternatives to Huawei before any ban was announced. Previously, the U.K. had also vocally condemned the Chinese government’s new national security law and continued authoritarian crackdowns in Hong Kong, a source of tension in U.K.-China relations over the last year.

India provides another prime example of rapidly heightening tensions with the Chinese government. First, border violence between India and China resulted in the deaths of at least 20 Indian soldiers. This sparked calls within India to boycott Chinese goods. And the Indian government announced at the end of June it was banning 59 Chinese apps from the country—including very popular applications like messaging, payment and social platform WeChat and video-sharing app TikTok, the latter of which had its highest number of global users located in India. Now, it seems possible that India might ban Huawei altogether in the event of any further escalations.

Many countries have expressed concern about the rise of Chinese technology companies, worrying that these firms may be acting at the behest, explicitly or not, of the Chinese government to censor certain content or collect data on users. Sometimes these concerns are voiced explicitly through public statements from elected officials; sometimes they are expressed more subtly through policy and strategy around digital supply chain security or through representatives in closed-door meetings. But either way, Huawei is a persistent subject of this anxiety in many parts of the world. 5G is a critical telecommunications technology, and there is good reason for countries to be concerned about the national security risks posed by Huawei’s entanglement with the Chinese government.

But even if some governments are shifting their stance on allowing—or at least not discouraging—the use of Huawei equipment in 5G networks, that doesn’t necessarily have to do with the Trump administration. Domestic political factors play a role: shifting stances in India cannot be separated from heightening India-China political tensions, and the same goes for the link between the U.K. government’s decision and its tensions with the Chinese government. In some cases, like in Singapore, governments have limited Huawei’s foothold in the country’s 5G systems without imposing outright bans, a decision that’s perhaps not quite the alignment the administration might tout. Singapore’s stance also underscores that some countries are still in a tricky position managing relationships with both Washington and Beijing.

And in light of a largely confused, contradictory and poorly executed U.S. diplomatic effort to convince allies and partners to ban Huawei, it would be a leap—and a big one—to attribute all this to the current White House. The administration’s messaging on the Huawei campaign has long been a mix of economic and security rhetoric infused with clear political motives. In December 2018, for example, President Trump suggested that he might stop efforts to prosecute a Huawei executive if doing so could help secure trade concessions from Chinese officials. Real security risks were used as political props in a trade war.

This is not to say the Trump administration’s continued sanctioning of Huawei has had no impact. Before the U.K. issued its ban decision, for example, Oliver Dowden—the U.K. secretary of state for digital, culture, media and sport—noted the U.K.’s position was “not fixed in stone,” and a spokesperson for Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that U.S. sanctions on Huawei could impact Britain’s decision on using Huawei in its networks. Likewise, the Telegraph reported before the ban was announced that an internal U.K. government report cited the U.S. sanctions as reason to reassess Huawei’s security risks, because the additional restrictions would force Huawei to use untrusted technology and elevate the risk to the United Kingdom if it continued to use Huawei critical infrastructure tech.

But it would be fundamentally inaccurate to characterize recent shifts as primarily the product of a well-executed U.S. diplomatic campaign. As tensions between the U.S. and China continue to rise and as the November presidential election approaches, it will grow even more likely these self-serving political drivers—desires for “better” trade deals, and efforts to look “tough” on a Chinese tech giant—are fueling decision-making, regardless of what real security risks are at play.

Policy responses to Huawei security risks—and to risks posed by really any hardware and software in the U.S. digital supply chain—don’t have to be this way. The U.S. government has the opportunity to develop objective, consensus-based trust criteria for hardware and software systems. It could then use those criteria to make and explain evidence-based analyses on the risks posed by technology like Huawei’s 5G equipment—as well as developing strategies about what to do about it. This is a process that would help the U.S. build a robust, long-term strategy for making digital supply chain security decisions. And in Huawei’s case, where there are clear national security risks surrounding backdoors (vulnerabilities inserted at a government’s behest), bugdoors (accidental flaws which the government says to leave in place) and regular vulnerabilities (just plain accidental), this shouldn’t be difficult. Quite the contrary, in fact.

Yet politics and posturing remain the primary drivers of administration actions against Huawei, despite the real security risks. These realities—the political drivers and the real risks—are not mutually exclusive. Recognizing the fundamental problems with how the Trump administration has handled this saga is important not only for understanding the U.S. campaign against Huawei, but for building a better U.S. policy on this issue going forward.