The View From Riotsville, U.S.A.

A review of Sierra Pettengill’s documentary film, “Riotsville, U.S.A.” (2022).

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A review of Sierra Pettengill’s documentary film, “Riotsville, U.S.A.” (2022).

***

In 2013, the police department of Morven, Georgia, population 565, acquired $4 million worth of military equipment, including armored vehicles, rifles, three boats, and scuba gear—despite a conspicuous lack of nearby bodies of water. Two hundred miles west, the police chief of Bloomingdale, Georgia, population 2,713, justified his department’s acquisition of four grenade launchers with the need to send a message that his “officers are armed to meet any threat,” even though no such threat had necessitated the use of deadly force on anyone during his 20 years leading the precinct. And in Keene, New Hampshire, population 23,000, local officials said the need to patrol the annual Pumpkin Festival “and other dangerous situations” demanded the acquisition of an armored tactical vehicle.

How exactly did we get here? When did it become commonplace for police departments to clamor for armored personnel carriers (a battlefield vehicle resembling a tank) that were previously used in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq? At what point did police officers come to resemble Rambo more than Andy Griffith?

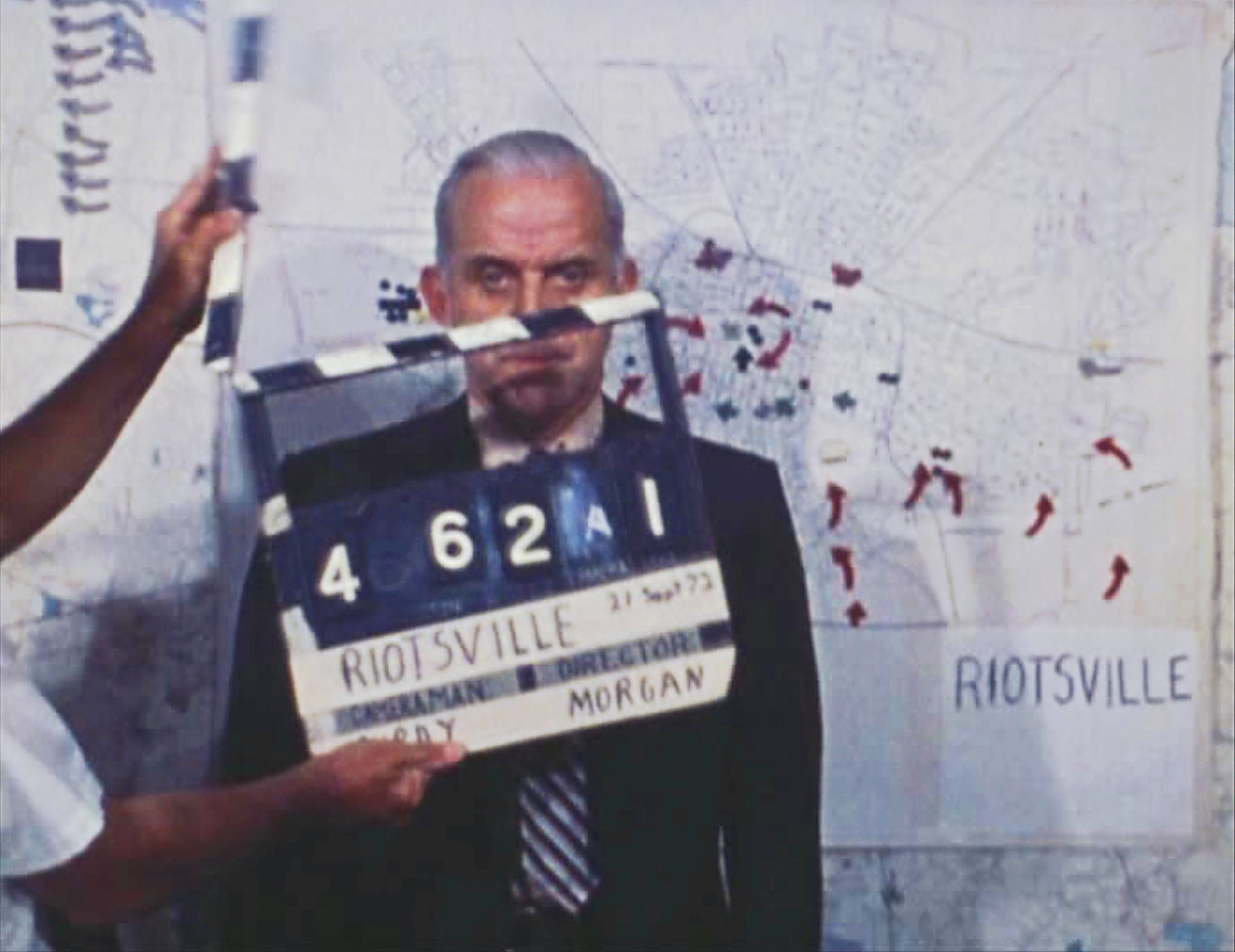

Theories on police militarization abound, but filmmaker and archival researcher Sierra Pettengill offers new answers—in both style and substance—in her recent documentary, “Riotsville, U.S.A.” In the late 1960s, amid uprisings in Detroit, Newark, and Watts, the U.S. military stood up model towns called Riotsvilles to teach police departments how to quash civil unrest—and filmed it. In Pettengill’s documentary, which was made entirely from archival footage, we see soldiers dressed as rioters parade through these plywood main streets—“Anywhere, U.S.A.,” as one reporter at the time called it. The faux rioters’ hippie wigs and gesticulations approach high camp, but their faux adversaries—the soldiers firing tear gas canisters and shaking down the would-be rioters for the onlooking police chiefs learning how to disperse riots in their hometowns—look all too real.

The footage sat in public archives for decades, until Pettengill began digging around after reading about Riotsvilles in Rick Perlstein’s book, “Nixonland.” In Pettengill’s hands, these archival finds conjure a security-state dreamscape set to a polyphonic soundtrack. Yet, rather than focus narrowly on these fictional towns and their “dream riots,” Pettengill, aided by lyrical narration from Tobi Haslett, tells the story of how this dreamscape became a reality. By placing this bizarre footage in the context of federal responses to civil unrest, “Riotsville, U.S.A.” becomes a visual journey of police militarization from its inception—a phantasmic vision of the path taken.

The False Promise of the Kerner Commission

Historians of police militarization often focus on recent decades to explain the trend, and for good reason. The so-called war on drugs and war on terror provided the justifications and motivations for inflated police department budgets, military weapons transfers, information sharing between the military and police, and cross-training in special weapons and tactics (SWAT) teams, which are modeled after military elite special operations units. Paramilitary deployments like SWAT teams increased dramatically in this period, up 1,400 percent between 1980 and 2000, from an average of 3,000 deployments in the 1980s to an average of 45,000 deployments by the year 2000. Police militarization during this period was also a two-way street. Left with what it perceived as a military without a mission at the end of the Cold War, the government began to involve the military in drug enforcement, border control, and other “domestic support” operations.

Though police militarization no doubt accelerated from the 1980s onward, Pettengill makes a compelling case that the process began in earnest as early as 1967. That year marked the founding of President Lyndon Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission after its chair, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. Pent up frustrations over the war in Vietnam and the effects of centuries of systemic racism had finally exploded across several U.S. cities, and the Johnson administration felt pressure to act. Helmed by Kerner and “11 of the least revolutionary people” in the country, according to Pettengill’s narrator, the commission was established by executive order to investigate and make recommendations with respect to:

(1) The origins of the recent major civil disorders in our cities, including the basic causes and factors leading to such disorders and the influence, if any, of organizations or individuals dedicated to the incitement or encouragement of violence.

(2) The development of methods and techniques for averting or controlling such disorders, including the improvement of communications between local authorities and community groups, the training of state and local law enforcement and National Guard personnel in dealing with potential or actual riot situations, and the coordination of efforts of the various law enforcement and governmental units which may become involved in such situations;

(3) The appropriate role of the local, state and Federal authorities in dealing with civil disorders; and

(4) Such other matters as the President may place before the Commission.

Behind the scenes of this wide-ranging mandate, Pettengill showed how Johnson made his true intentions clear. Before appointing Oklahoma Sen. Fred Harris to the commission, Johnson leaned on him to toe the line. Harris recalled that Johnson called him right before the appointment announcement with a warning: “I’m going to appoint that commission you’ve been talking about ... and another thing, Fred. I want you to remember that you’re a Johnson man … if you forget it, I’m going to take my pocket knife and cut your [blank] off.”

Despite Johnson’s best efforts, the Kerner Commission’s 1968 report was anything but the milquetoast document many had predicted it to be. “Our Nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” the report declared. “What white Americans have never fully under stood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

The report became a runaway bestseller and nothing short of a societal bombshell, as Pettengill’s archival footage illustrates so well. “The report of the president’s commission on riots will tell white America that the United States is a racist country,” one major network news anchor soberly says over scenes of schoolchildren buying paperback versions of the report. The commission called for massive investment into mostly Black cities to spur employment, improve schools, accelerate desegregation, and seed other major initiatives. All told, the recommendations totaled $2 billion per month, roughly the same expenditure of the Vietnam War at the time.

Even the watered-down version of the report that eventually made its way into the public delighted some revolutionary activists at the time. In just one example, Pettengill’s narrator reads a statement from H. Rap Brown, who commented on the report’s release from a Louisiana jail cell: “The members of the commission should be put in jail under $100,000 bail each because they’re saying essentially what I’ve been saying.”

But at the end of the day, the commission was just an inquiry, and the report contained only its nonbinding recommendations. Ultimately, the rubber never met the road. As one Black intellectual in the film said on Public Broadcast Laboratory (a precursor to PBS and a rich source of archival material from which Pettengill draws judiciously): “That’s what we do in this society. We appoint a committee, and we investigate. Ergo, something’s being done. That’s just not true.”

For all the report’s bold recommendations, the Johnson administration essentially implemented just one, a back-page “supplement on control of disorder.” Less than six months after the report’s release, Johnson signed the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968, which authorized $400 million in grants to states for new equipment and training to police departments. The new legislation, which was also a reaction to the Warren Court’s criminal procedure jurisprudence and much of the population’s general fear of violent crime, allowed states to acquire M1 military rifles, tanks, bulletproof vests, and other equipment. The federal government encouraged these purchases by covering up to 90 percent of the cost.

The implementation of the control-of-disorder supplement is a crucial case study in the story of police militarization Pettengill aims to tell—one of switchbacks, forks in the road, and sunnier paths not taken. Though not mentioned in the film, Pettengill’s narrative suggests a throughline from the 1968 legislation to the 1033 Program of 1989, which authorized the transfer of surplus military-grade equipment from the Pentagon to police agencies at the federal, state, and local levels—free of charge. The program both enables acquisition of military equipment and incentivizes its use thereafter; the federal government requires police departments to use 1033 equipment within one year of receiving it. Similar to the 1033 Program, the 1122 Program allows for police agencies to purchase new military hardware at no cost. This program primarily allows police agencies to maintain equipment acquired through the 1033 Program through the purchase of replacement parts.

With an absence of violent crime warranting military-grade armaments in most, if not all, American cities, the overkill and incongruence verges on farce. In one of Pettengill’s archival gems, a band of police officers ride inside the “WitchCraft” tank, each tumbling out and lumbering awkwardly to attention after the armored vehicle churns to a stop. They clearly fall short of their intended effect, as a news reporter chuckles to himself just off-screen. The pantomimed responses and exaggerated shows of force call to mind the darkly humorous HBO series “The Rehearsal,” and one almost expects a laptop-clad Nathan Fielder to be waiting off-screen as well. But this theater of the absurd has more acute consequences. In the absence of war, this war machine was likely used to respond disproportionately against communities of color. This is as true now as it was in 1968.

Tear Gas: A Star Is Born

Toward the end of the film, we finally see where the paths taken begin to lead. “We’ve heard about Chicago, but we’ve been living through Miami Beach,” declares the film’s narrator. For Pettengill, the two cities are metonymies for the 1968 Democratic National Convention and Republican National Convention, respectively. The events of the former became popular national history, worthy of an Aaron Sorkin Hollywood treatment, and the latter, a footnote.

It’s not until Miami Beach, the only footage in the film of an actual riot and the methods for its dispersal in action, that we meet one of Pettengill’s main characters: tear gas. Wafting into frame from above, below, and sideways, tear gas blankets Liberty City, the Miami-area neighborhood where the riots occurred, not far from the Republican National Convention. One scene shows a converted insect repellent spray truck pumping tear gas onto a quiet, home-lined street. We then learn that police had instituted a curfew, but used so much tear gas that residents were forced out of their homes to escape it.

This “nonlethal” method of crowd control is one of the Kerner Commission’s most enduring legacies. “The Commission recommends that, in suppressing disorder, the police, whenever possible, follow the example of the U.S. Army in requiring the use of chemical agents before the use of deadly weapons,” wrote the authors of the report. In another scene, we meet the CEO of Federal Labs, Inc., the largest manufacturer of tear gas at the time, who touted his product as a “public service” and a “humane method of handling difficult situations,” just as a dentist administers Novocaine to yank out a rotten tooth. Another scene notes the accusations against the Pentagon for violating chemical weapons bans with its use of tear gas in Vietnam, and the military’s response that it’s permissible in war because it’s used at home by domestic law enforcement.

The police’s adoption of the Kerner Commission’s recommendation for “nonlethal” tear gas usage eventually eclipsed the military’s. During the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, 22-year-old Sarah Grossman died after exposure to tear gas and pepper spray deployed by police in Columbus, Ohio, as part of routine and legal crowd control measures. Though this tragic death was a rare case, the use of tear gas and pepper spray was not. Between May and October 2020, U.S. domestic police forces used tear gas at least 175 times and pepper spray at least 148 times against overwhelmingly peaceful protesters, according to research groups Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture, which identified, verified, and archived over 1,000 incidents of police violence against protesters that summer. Although the researchers did not track the number of injuries caused by the chemical irritants, a 2017 study concluded that the “use and misuse of these chemicals may cause serious injuries,” “leading to unnecessary morbidity and mortality,” despite being considered generally safe by police. The use of chemical irritants during the summer of 2020 was even more dangerous given the respiratory coronavirus circulating through the population at the time.

***

Pettengill’s history of police militarization is not a hidden one—the source material was neither leaked nor declassified. The footage, shot by the government and in the public domain, was covered extensively by newspapers and major networks at the time. In this sense, stories of militarized police and their use of force on communities of color are nothing new. And yet, despite working with publicly available footage of a well-known phenomenon, Pettengill manages to communicate the absurdity and immorality of police militarization in a fresh way. By letting the archival footage tell the story, she shows how, after building Riotsvilles in the image of any American city, police departments then remade these same cities in the image of Riotsvilles.

In an interview last month, Haslett said that one of the film’s main themes is the “mechanism of forgetting, which is important for reproducing social conditions as they now stand.” Haslett’s observation gets at why it’s important to investigate the origins of things, especially repressive social forces. To counter this business of forgetting, Pettengill busies herself with remembering. By showing how police militarization was made, “Riotsville, U.S.A.” seems to suggest how it could just as easily be unmade.

.png?sfvrsn=48e6afb0_5)