Warren Has a Plan for Disinformation—What About Everyone Else?

The 2020 U.S. presidential election is playing out in the shadow of disinformation, but few candidates are promising to take action against it. Elizabeth Warren has a plan, but it’s not perfect.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The 2020 U.S. presidential election is playing out in the shadow of disinformation, but few candidates are promising to take action against it.

Questionable information about presidential candidates abounds in the upcoming election. The content and claims vary. There are those abject lies, like the tweet citing a fake news story to claim Pete Buttigieg harmed dogs as a teenager. Other examples are misleading, such as the heavily edited video that takes Joe Biden’s comments about culture so out of context that he appeared to be espousing white supremacist rhetoric. One thing remains consistent: Consumption of mis- and disinformation by unsuspecting voters threatens to shape the nature and, potentially, outcome of the election.

Indeed, one-third of Americans view misleading information as a threat to the election, and 59 percent polled think it is difficult to discern factual from misleading content. So, where in the various candidates’ platforms are the commitments to tackle disinformation? In most cases, they’re entirely absent. Democracy derives legitimacy from the ability of citizens to make informed and free decisions, particularly during elections, so the public should expect more from candidates vying for the country’s top job.

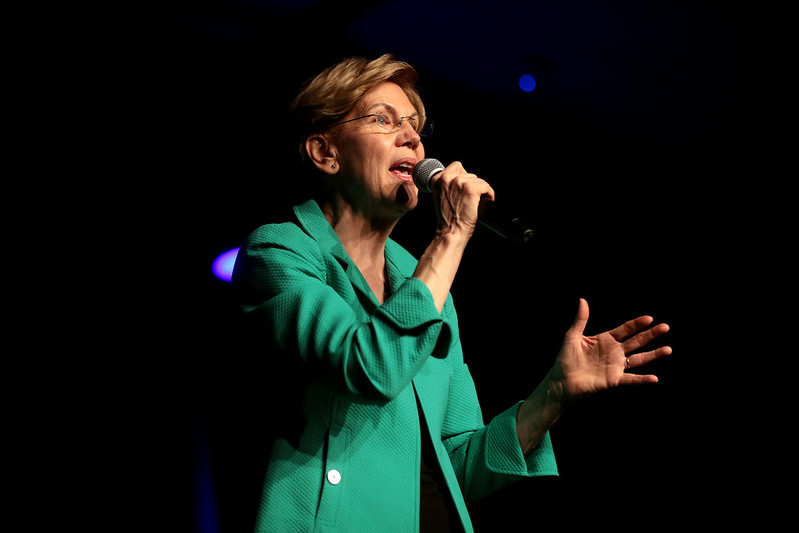

Some candidates mention the problem in passing, and a small collection have committed to doing something about the problem, including Pete Buttigieg, Elizabeth Warren and Andrew Yang, who has since dropped out of the race. President Trump, though he continues to occasionally amplify dis- and misinformation, has approached the issue from a different angle. His campaign website includes several references to “fake news,” and his “official campaign strategy survey” asks supporters if the incumbent should “do more to hold the Fake News media accountable?” Among the collection of candidate proposals, Warren’s pledge is unique for its recognition that politicians are part of the disinformation problem.

Warren’s plan to fight digital disinformation is broken into three parts—with sections focusing on her campaign, on private industry and on her plans for what her administration would do to tackle disinformation. The opening section of Warren’s statement is a simple three-point commitment that her campaign will not engage in or benefit from disinformation. This section is less a detailed policy proposal and more a message that she “will not tolerate the use of false information or false accounts to attack my opponents, promote my campaign, or undermine our elections.”

The second section focuses on holding industry to account, calling on certain social media platform executives by name to act on five points: increase information and resource sharing with the government, label “content created or promoted by state-controlled organizations,” do more to notify users exposed to disinformation, “create clear consequences for accounts that attempt to interfere with voting,” and provide more data to the research community.

The third section outlines Warren’s plan to deal with disinformation, should she win office. Also in five points, this section promises to implement “civil and criminal penalties” for engaging in voter suppression; bring back the role of National Security Council cybersecurity coordinator; host an international summit on responding to disinformation; create rules to facilitate information sharing by industry to government; and explore further sanctions against countries interfering in elections, namely Russia.

The other two candidates who have announced plans to combat disinformation were far less ambitious. Andrew Yang pledged to address disinformation but put the onus solely on industry. Pete Buttigieg acknowledges that disinformation is a problem but frames it as a security issue, offering solutions using the intelligence community, rather than engaging industry or aiming to change rules around political campaigning.

Buttigieg’s approach is to “revitalize our intelligence services with an investment in new people and a renewed commitment to tools like human intelligence and next-generation information operations.” He goes further, advocating for the use of U.S. information operations to “disseminate the truth,” particularly abroad. This approach has two shortcomings. First, it suggests that simply adding more “truth” will outweigh the disinformation, ignoring all the emotional triggers and cognitive biases so often at play in influence operations. Second, it positions the disinformation as originating from foreign sources alone, ignoring the melange of domestic actors who also push disinformation. As Benkler, Faris and Roberts found in their sweeping study of the American information ecosystem in Network Propaganda, while foreign actors are a threat, they are minor compared to domestic actors who want to persuade voters.

For its part, the Democratic National Committee has announced efforts to combat online disinformation, focused mostly on identifying and refuting examples of disinformation rather than committing not to use or benefit from such influence campaigns. What is refreshing about the Warren plan is that it goes further: It acknowledges that disinformation is both a domestic and a foreign problem, one to which political campaigns contribute. And Warren puts the responsibility for addressing the issue on both industry and government. Warren’s plan is not without problems, though. Most of the shortcomings deal with scope.

While her plan to bring back the role of cybersecurity coordinator at the National Security Council is a good one, the focus on cyber does not accurately capture the nature of the disinformation problem. This is an issue that is driven as much by information and politics as it is by technology.

To make a serious difference, whoever takes on the role of cybersecurity coordinator must understand the infrastructure, the manipulation of information and the effects that information has on audiences.

The relationship between cyber and information is a lot like that of plumbing infrastructure and water. The former controls how the latter is distributed and can affect the flow and quality of the water. But the importance and role of water to people goes beyond its distribution and access to it. Water has many uses beyond for drinking—it is vital to existence, and its quality can have serious and lasting consequences. Focusing on cyber alone, or even foremost, takes a technical approach that is akin to worrying mostly about the plumbing but not the water and its importance to society. Cyber is the infrastructure, both the hardware and the software, that processes and distributes information. It, likewise, can affect the flows and quality of that information. Information, by contrast, is produced and consumed by people. Factors independent of cyber can shape perspectives—how information is presented, processed and understood can have a profound impact on its reception. This becomes more a cognitive problem than a purely technological one.

And then there is Warren’s approach to regulating private industry. Warren’s strategy would demand that U.S.-based companies implement plans that might satisfy U.S. interests, such as forcing platforms to “clearly label content created or promoted by state-controlled organizations.” To enforce this policy, clear guidelines would need to be provided to distinguish public broadcasters from state media organizations. What constitutes “state-controlled” and who makes this determination? One way to distinguish between public broadcasters and state media is by looking at governance structures and transparency reporting. But arguments about whether a given outlet qualifies as state media ultimately end up focusing on values: Western publicly funded outlets are considered good because they are independent, even though they are government funded and have mandates to share democratic values, while the media outlets tied to non-Western states are considered bad because the controlling state does not share our values. If a government backslides, does the labeling of its affiliated media outlet change with it? Where does this leave outfits such as AJ+, run by the Aljazeera Media Network, itself funded partially by the Qatari government?

A recommendation like Warren’s requires first outlining the criteria by which such media outlets should be judged and treated, and considering the international repercussions of those decisions. A model that might work for the U.S. can easily be adopted by other countries to control information in their information ecosystem in ways that democratic governments may not appreciate. Could Vietnam, for example, demand that BBC or Voice of America be labeled as state-controlled media? From a Vietnamese perspective, these outlets might be viewed as such. Disinformation is a global problem, and addressing it requires thinking outside a U.S. paradigm. That’s not a politically useful fact for a candidate running for U.S. office, but it is the reality of the disinformation challenge.

Adopting a more global-minded approach to tackling disinformation would also go a long way in giving the U.S. the moral standing needed to support Warren’s plan to “convene a summit of countries to enhance information sharing and coordinate policy responses to disinformation.” The U.S. does not enjoy the best reputation when it comes to data protection and privacy. Following the Snowden leaks, European Union regulators moved to curtail the transfer of data on European citizens to the U.S. amid growing distrust of the U.S. government’s approach to privacy. The Cambridge Analytica scandal only deepened European skepticism of U.S. data-privacy practices. Domestically, it behooves presidential candidates to put forth a vision of U.S. leadership. But Warren (and other candidates) might do better to first listen and understand how disinformation is affecting different countries as an approach to international engagement.

Warren’s plan also focuses too narrowly on disinformation, neglecting more subtle forms of influence operations. Disinformation is one tactic among many used in influence operations, organized attempts to achieve a specific effect within the information environment. More subtle tactics include running targeted advertising, spreading provocative content within highly networked communities, mobilizing followers to action (including disinformation but also memes and leaked content), and manipulating online news and search algorithms.

Putting the focus on disinformation alone reduces a systemic issue to a problem about content, ignoring the tactics or activities involved in influence operations, such as behavioral advertising.

Warren’s plan relies on a false dichotomy between fact and fiction. The act of determining what is true can be quite subjective, or as philosopher Jurgen Habermas noted, “[T]he concept of truth is interwoven with that of fallible knowledge.” In the context of political opinion, making the distinction between truth and fiction—and how to regulate it—is often vexed.

Much of the outrage related to Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data to target voters was not about disinformation but rather how data is aggregated on citizens and then used to persuade them. The bigger question is not about misinformation but about persuasion more broadly, particularly when it is enabled through behavioral tracking that allows individuals to be targeted based on their beliefs, preferences and habits. When does manipulation of information and targeting become so aggressive that it takes away the autonomy of voters to make decisions of their own free will? As it stands, there are few lines in the sand currently around what is and is not acceptable in using technology to persuade target audiences.

Warren should consider restrictions on the use of behavioral advertising and limits on the actors who can legitimately engage in influence operations during an election. Warren addresses some of these issues in a different plan that promises to change existing campaign finance laws to include regulations for online political advertising, but she stops short of specifically mentioning targeted behavioral advertising.

Moreover, although it is imperative that election laws be updated for a digital age, focusing on paid-for ads neglects organic or unpaid content spread through online communities with followers built up over years. According to social media marketing company Socialbakers, some of the most popular political Facebook pages in the U.S. are purportedly run by third parties, each with millions of followers, such as Occupy Democrats (8 million), Secure America Now (3.4 million) and Patriots United (2.7 million). These pages are ostensibly not controlled by any political party or candidate, but in some cases they actively support a particular campaign. With audiences built up over years, they need not pay for advertising to engage voters. But these pages can reach out to a high volume of Americans by posting content that encourages followers to retweet and share the posts with their own audiences. Considered in this context, while Warren’s campaign may be able to abide by her pledge not to use or benefit from disinformation, it will be far harder for her to rein in her supporters. Some super PACs, in particular, will be tempted to engage in this grayer side of influence operations on candidates’ behalfs, setting up “grassroots” organizations and related Facebook pages and groups or gaming online algorithms for better search returns.

Screenshot of a post by the Facebook page Occupy Democrats. According to the fact-checking website Snopes, the claims made in this post have not been proved.

Yet Warren is uniquely positioned to take a stand against these tactics. Having promised not to take campaign money from super PACs or lobbyists makes it easier for Warren to distance herself from this type of third-party activity. Of course, should a third party decide to set up and fund a super PAC to support Warren, there is little she can do to stop it beyond asking. Indeed, to completely abide by her promise, Warren will have to disavow supporters, third-party community pages or PACs alike that use these tactics. Nonetheless, at least Warren is taking a stand against disinformation. Unfortunately, Democratic candidates who make this type of pledge will find it unreciprocated by their opponent in the general election. Indeed, nine out of 10 of the top-ranked political Facebook pages (according to Socialbakers) openly support Trump.

Screenshot of Socialbakers’s ranking for most followed political Facebook pages in the U.S. on Feb. 19.

Warren should be applauded for taking a stand. It is refreshing to see a candidate acknowledge the systemic problem of disinformation—including the role that politicians play—and pledge her campaign to be better. Let’s just hope she (and her supporters) can succeed in keeping that promise and setting an effective example.