Was an Attempt to Take Over a Tennessee Courthouse in 2010 a Preview of Jan. 6?

In both the attack on the Capitol and the standoff at the Tennessee courthouse, members of the Oath Keepers promoted self-serving, distorted “patriotic” rhetoric to justify criminal acts against government officials.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

March 2 marked the start of the first trial of a defendant charged with federal crimes associated with the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capital. Guy Reffitt is standing trial for various offenses, including bringing a firearm into the assault. Also present during the Jan. 6 attack were a number of people dressed in paramilitary gear who appeared more organized than the rest of the mob. As has been alleged in subsequent Jan. 6 federal prosecution court pleadings, they were members of a self-proclaimed militia-type group called the Oath Keepers who physically breached the security of the Capitol and assaulted the building in a “stack” formation. Based on this apparent attempt to “take over” the Capitol by means of force to prevent the lawful transfer of power, just over one year later, on Jan. 12, a federal grand jury returned an indictment charging 11 Oath Keepers members, including founder and leader Stewart Rhodes, with seditious conspiracy and other related offenses.

This was not the first time, however, that a member of the Oath Keepers was involved in a self-declared takeover of a government building. On April 20, 2010, Darren Huff—a self-proclaimed member of the Oath Keepers and the “Georgia Militia”—traveled with weapons from Georgia to join in a group, many of whom were also carrying firearms, in Madisonville, Tennessee, for the purpose of taking over the Monroe County Courthouse to “arrest” various county government officials for being “Declared Domestic Enemies” having committed “treason.”

While serving as a prosecutor at the U.S. Department of Justice, I prosecuted Huff. And while watching the current seditious conspiracy case against the Oath Keepers, I believe that a number of lessons from Huff’s case can be useful to law enforcement and prosecutors. Before applying those lessons, it’s worth noting the facts of Huff’s case. Why was Huff ready to “arrest” these county officials? His justification for the courthouse standoff centered on his belief, as reflected in the “Affidavit of Criminal Complaint” he carried with him on April 20, that Tennessee officials had committed “treason” by being engaged in “constructive levy of war against the United States and Citizens of the United States” through “forcible resistance” to the U.S. Constitution “with the intent and having achieved some success installing a rival government.”

After arriving in Madisonville on April 20 to participate in the “arrests” of selected government officials, Huff gathered with about 50 people and engaged in an armed standoff with law enforcement officers outside the Monroe County Courthouse. These law enforcement officers had been assembled in advance to prevent an effort to “take over” the courthouse. Unlike the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, the armed protesters did not attempt an assault on the county courthouse, largely due to the presence of nearly 100 local, state and federal law enforcement officers.

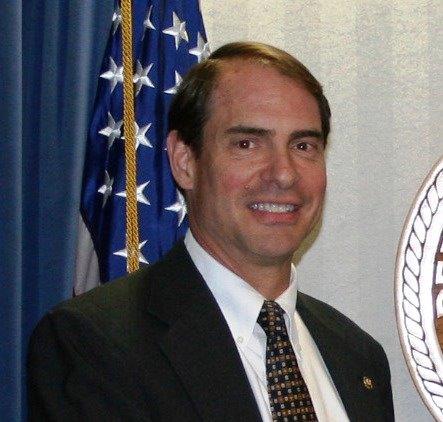

Huff’s justification for his desired “arrests” lay in a “Criminal Complaint” and “Citizen’s Arrest Warrant” that had been drawn up in March 2010 by a locally known political agitator and former (and court-martialed) U.S. Navy commander, Walter Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick had previously sought—unsuccessfully, to his great frustration—on three occasions to present an indictment before a local grand jury charging then-President Obama with fraud and treason.

On April 1, 2010, more than two weeks before the incident, Fitzpatrick (with the assistance of Huff) had attempted to arrest the local grand jury foreman and the county sheriff at the Monroe County Courthouse under his “Citizen’s Arrest Warrant.” In a bit of irony, Fitzpatrick was himself arrested that day for disorderly conduct and attempting to disrupt a government meeting.

Fitzpatrick was scheduled to make a court appearance in Madisonville with regard to his criminal charges on April 20, 2020. With that court date in mind, Huff engaged in a number of communications with various others prior to April 20 seeking to organize a group to appear at the Monroe County Courthouse that day to “arrest” the offending county officials.

Following the April 20 standoff, a federal grand jury indicted Huff for transporting firearms in interstate commerce (from Georgia to Tennessee) with the intent to use the weapons in furtherance of a civil disorder, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 231(a)(2). This is one of the same charges that has been brought against Guy Reffitt, an alleged member of the "three Percenters" anti-government group.

A “civil disorder” is defined under the law as any public disturbance involving acts of violence by an assembly of more than three people that causes either the immediate danger—or actual result—of damage or injury to property or a person. Given that there was no actual clash with law enforcement or any type of riot, the federal crime of inciting a riot didn’t apply to the Madisonville event. The charge of transporting a firearm in furtherance of a civil disorder was based on the combination of Huff’s travel to Madisonville with firearms to participate in the arrest of government officials and his participation in an armed standoff at the courthouse with multiple people.

Testimony at Huff’s trial indicated that, prior to April 20, Huff had told several people in his hometown that Fitzpatrick had been “wrongly arrested,” and that he was planning on arming himself with weapons (including an AK-47) and joining up with others to “take over the city” that day. Huff had also asserted that he fully intended to proceed to Madisonville on April 20 to arrest the offending county officials, and that he would be bringing weapons “because ain’t no government official gonna go peacefully.”

Huff was convicted in 2011 following a trial in federal court in Knoxville, Tennessee. On his appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, Huff tried unsuccessfully to challenge both the evidence introduced at trial and the constitutionality of the federal statute that he violated.

As the prosecutor in the Huff case, I watched the assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6—and the involvement of the Oath Keepers—and felt like I had seen similar events on a smaller scale. In both the attack on the Capitol and Huff’s standoff, members of the Oath Keepers promoted self-serving, distorted “patriotic” rhetoric to justify criminal acts against government officials.

First, it is critical for law enforcement and government officials to take the threats of persons and groups espousing militant or violent anti-government views quite seriously—and take precautionary action as necessary to prevent inciting words from becoming violent actions. Since 2010, and certainly since 2016 and later in 2020, extremist political and paramilitary anti-government rhetoric has grown to the point that what had been considered “fringe” rantings has alarmingly merged in more “acceptable” extreme partisan viewpoints. While there should not be any government infringement on protected First Amendment political or personal speech, communications and speech that encourages, promotes or conveys threats of violence should always be carefully considered and evaluated—and taken seriously—without regard to whatever political bent to outlook.

In the days preceding the April 20, 2010, Madisonville confrontation, various local, state and federal law enforcement agents, together with the prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, actively shared on a real-time basis all “threat intelligence” information on what appeared to be an active potential threat to public safety. A temporary “task force” was created to centralize and manage all relevant information being gathered from various sources, including social media chatter and witness interviews. This was done in the interest of public safety, without suppressing or downplaying information that might conflict with the views held by higher-up state or federal powers-that-be who might be inclined to agree with protesters’ political views. It appears that this was not the case in the days and weeks preceding Jan. 6.

Second, while fully respecting the First Amendment right to assemble peaceably, there should be sufficient law enforcement or public safety preparation. Any type of (peaceable) assembly might quickly devolve or degrade into violence—whether by design of the participants or perhaps in response to adverse provocation. Prior to the April 20 incident in Madisonville, even given a short window of time, the local police department, the state prosecutor for that area, the FBI, and federal prosecutors extensively considered the potential risks to public safety in an active risk assessment. That planning ensured sufficient resources for the worst-case scenario.

Finally, all those who undertake actions—or attempt to do so—that cross the line from theoretical advocacy to facilitating or supporting criminal conduct should be held accountable under the appropriate laws. Accountability may take the form of prosecuting one individual, such as Huff, if that represents the only feasible case with the strongest evidence. Or having the resolve—and devoting the necessary resources—to undertake a much broader effort to prosecute numerous participants and co-conspirators where the evidence demonstrates actions taken in concert, and with a common purpose, that brings harm to public institutions and government. As is reflected in the large number of ongoing Jan. 6 prosecutions, the actions taken that day posed a grave threat to the lawful operation of the U.S. government. Yet some politicians have notably sought to minimize or purposefully disregard the nature of this kind of domestic threat and have even advanced claims that the assault was undertaken by anti-Trump operatives, which may only serve to embolden those like Huff who continue believing that actions like the Jan. 6 assault are acceptable and justified in the name of “liberty.” Wherever the evidence leads, and however high it goes in the former administration (or associates thereof), it is vital to the nation’s democratic system and social values that all who are responsible, and not just the ideological foot soldiers, be held accountable.

As the Huff prosecution demonstrated, there are many people of otherwise “normal” backgrounds who, under the right (or wrong) circumstances, are encouraged and inspired by like-minded leaders or followers in the echo chamber of social media. These people can convince themselves that they are among the ones “in the right” and are justified in taking “all reasonable force” in the defense of what they see as “liberty.” Huff responded to what he saw as a patriotic “call to action” by a leadership figure and was not dissuaded even when FBI agents and people in his own town intervened (as seen in trial testimony). When looking back at the Huff prosecution, and the politically charged environment that led to the Jan. 6 assault, keep in mind what Samuel Johnson wrote more than 200 years ago about those who wield false patriotism as a weapon: “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel."