What Happens If Trump Really Decides to Decertify the Iran Deal?

The Washington Post reported yesterday that next week, President Trump may announce that he will “decertify” the Iran nuclear deal because it is not in the interest of the United States to continue implementing it.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The Washington Post reported yesterday that next week, President Trump may announce that he will “decertify” the Iran nuclear deal because it is not in the interest of the United States to continue implementing it. The administration faces an October 15 deadline to certify to Congress that Iran is complying with the agreement and that it remains in the United States’s interest to follow it, as mandated by the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (42 U.S.C §2160e).

The announcement would be part of the broader introduction of a new U.S. strategy toward Iran that would address the country’s support for terrorism, involvement in Middle East violence and ballistic missile development, in addition to the nuclear issue. In a meeting with senior military leaders yesterday, Trump once again criticized Iran’s behavior and asserted that the country has “not lived up to the spirit of their agreement.” He did not say that Iran has violated any of its concrete obligations under the agreement.

However, the Post report makes it clear that no final decisions have been made at this point. It also indicates that even if Trump decertified the agreement, he would “hold off on recommending that Congress reimpose sanctions.” This caveat suggests that decertification might not immediately lead to the reinstatement of U.S. nuclear sanctions against Iran. Additional measures, either congressional or executive, would be necessary to actually reimpose sanctions.

Background

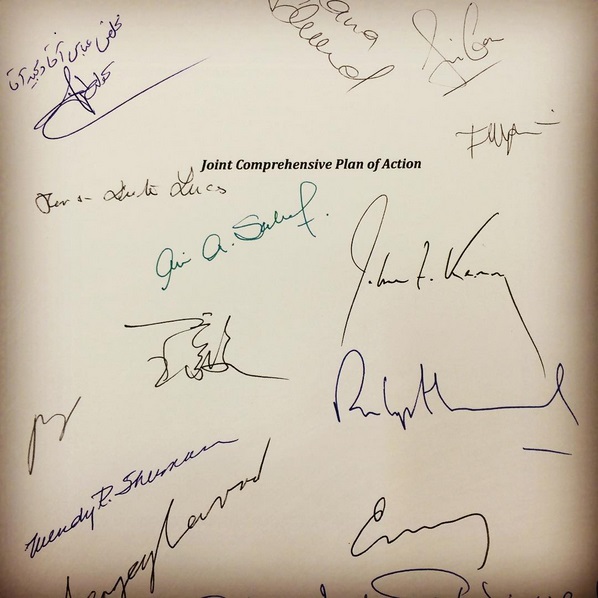

The Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was concluded between Iran and the members of the P5+1, as well as the E.U., in July 2015. Iran agreed to concessions regarding its nuclear program in return for extensive sanctions relief. The agreement was endorsed by U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231. Subsequently, on JCPOA “implementation day” on January 16, 2016, the U.S. and the E.U.. lifted most of their respective sanctions imposed in connection with Iran’s nuclear program, after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) verified that Iran has implemented its nuclear-related obligations under the JCPOA. Previous Security Council resolutions regarding Iran’s nuclear program have been terminated.

The Obama administration maintained that the JCPOA was not legally binding and, therefore, did not require Senate approval. The U.S. could stop implementing it at any time without violating its obligations under international law (see Jimmy Chalk’s post). In order to fulfill the United States’s commitment, the administration relied on pre-existing authorities that gave the president discretion in the application of sanctions against Iran (see Jack Goldsmith’s post and lecture). Specifically, the administration utilized existing waiver authorities that previous sanctions legislation had granted to the president. Executive orders allowed the president to impose other sanctions. Therefore, those sanctions could be withdrawn with relative ease.

The Obama administration’s stance that congressional approval was not necessary for concluding the Iran deal drew the ire of legislators and led to the enactment of INARA, an amendment to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954. The act required the president to submit any nuclear agreement with Iran for congressional review and imposed additional reporting and certification requirements to allow congressional oversight of the implementation of such an agreement. For current purposes, the key provisions are those regarding certification of compliance. INARA requires the president to certify every 90 days that Iran is in compliance with the JCPOA and that it remains in U.S. interest to suspend sanctions as part of the implementation of any agreement

(d)(6) COMPLIANCE CERTIFICATION.—After the review period provided in subsection (b), the President shall, not less than every 90 calendar days—

(A) determine whether the President is able to certify that—

(i) Iran is transparently, verifiably, and fully implementing the agreement, including all related technical or additional agreements;

(ii) Iran has not committed a material breach with respect to the agreement or, if Iran has committed a material breach, Iran has cured the material breach;

(iii) Iran has not taken any action, including covert activities, that could significantly advance its nuclear weapons program; and

(iv) suspension of sanctions related to Iran pursuant to the agreement is—

(I) appropriate and proportionate to the specific and verifiable measures taken by Iran with respect to terminating its illicit nuclear program; and

(II) vital to the national security interests of the United States; and

(B) if the President determines he is able to make the certification described in subparagraph (A), make such certification to the appropriate congressional committees and leadership.

Despite his vocal criticism of the JCPOA and repeated claims that it is inadequate, President Trump has previously certified that Iran is in compliance with the agreement. So far, the Trump administration has also extended the Iran sanctions waivers.

What Happens if Trump Decertifies?

If President Trump really does decertify the JCPOA, he would probably trigger major political and diplomatic blowback from the other parties to the agreement and perhaps more importantly, from Iran. The mere prospect of decertification has already provoked statements from multiple parties to the JCPOA urging the U.S. to continue implementing the agreement.

However, decertification would have no automatic consequences in terms of U.S. implementation of the agreement with respect to the continued suspension of sanctions that had been waived or rescinded under the JCPOA. In order to have such an effect, decertification must be accompanied by measures to reimpose sanctions.

Sanctions could be reinstated in several ways. Congress could introduce legislation to reimpose sanctions within 60 days of the deadline for certification. Such legislation would be entitled to INARA’s expedited consideration procedures (§2160e[e]). Alternatively, the president could decline to exercise the waivers that have suspended the implementation of sanctions legislation thus far. The president could also reinstate designations of Iranian persons and entities as Specially Designated Nationals (SDNs) pursuant to executive order. Such designations would also trigger secondary sanctions like those provided for in the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA), a law that restricts the access of third-country financial institutions with ties to Iran-related SDNs to the U.S. market. Finally, the U.S. could move to reimpose U.N. sanctions by triggering the “snapback” mechanism agreed upon in the JCPOA (more on that here). So far, the administration has not indicated that it intends to take any of those steps to unilaterally reimpose sanctions.

Thus, the Post’s report that the Trump plans to “hold off on recommending that Congress reimpose sanctions on Iran” is somewhat puzzling. The president does not really need Congress in order to reinstate sanctions that were lifted in the framework of the nuclear deal. He can do so by exercising authorities that he already has through waivers or executive orders. (For more information, see this CRS report that concluded: “It is unlikely that the President would require the approval of Congress” for unilaterally re-imposing sanctions.) The Post's report suggests that, in reality, the administration might not be in a hurry to gut the JCPOA by reneging on the U.S.’s core obligations under the agreement.

Decertification without reintroducing sanctions would allow the administration to express its dissatisfaction with the terms of the JCPOA for political gain while preserving the core of the agreement and providing an incentive for Iran to continue meeting its nuclear obligations. (Unless, of course, Congress moves to reinstate sanctions in response to the president’s decertification of the JCPOA.) The move might also intend to create leverage for potential renegotiation of the JCPOA, although there seems to be no appetite for that among the other parties to the agreement. In any event, it seems that the ball is now in Congress’ court.