What Happens When Courts Can’t Trust the Executive Branch?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Saturday, April 5, the Department of Justice indefinitely suspended Erez Reuveni, a senior immigration lawyer. His offense? Failing to “zealously advocate on behalf of the United States,” according to Attorney General Pam Bondi. Reuveni had recently been promoted to acting deputy director of the Justice Department’s Office of Immigration Litigation, partly for his work suing “sanctuary cities” opposing the Trump administration’s deportation campaign. But Reuveni committed Trumpworld’s cardinal sin: failing to exhibit total and unquestioning loyalty. In a hearing before federal judge Paula Xinis, Reuveni acknowledged that the government made a mistake when it deported Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, on suspicion of being an MS-13 gang member, to a notorious prison in El Salvador.

There is much to say about the litigation over Abrego Garcia. (Following the hearing, Xinis ordered the government to bring Abrego Garcia back to the United States, ruling that he had been detained and deported “without legal basis.” The Supreme Court has stayed the order as it considers the government’s appeal.) But I want to focus on what it means when the Justice Department suspends an attorney (and his supervisor) for candidly answering a judge’s questions. What happens when the courts realize that the government is requiring its lawyers to choose between dissembling to the court—risking their bar licenses in the process—and keeping their jobs?

The answer is nothing good. The Reuveni scandal is only the latest sign that, at least in the lower courts, a core principle guiding the relationship between the judicial and executive branches—the presumption of regularity, the courts’ baseline assumption that government officials act lawfully and in good faith—is in free fall. The reason is not that the courts are abandoning the principle; rather, the government’s own conduct is making it impossible for courts to trust that the government is operating honestly.

The Presumption of Regularity

The presumption of regularity is a deference doctrine whereby courts presume that government officials act lawfully. This means judges start from the premise that the government’s stated reasons for its actions are its true reasons and that its factual representations to the court are accurate. Although the presumption is rebuttable, it is not easily displaced, and the burden of proof falls heavily on the party challenging the government’s actions. Overcoming the presumption requires substantial evidence demonstrating irregularity, bad faith, or pretext.

The presumption serves the institutional needs of both the courts and the executive branch. It prevents courts from constantly becoming entangled in searching inquiries into the internal deliberations and motivations behind every government action. Such inquiries would overburden the courts, undermine the separation of powers, paralyze the executive branch, and chill necessary, lawful government action. While the presumption has never perfectly reflected reality—there have, after all, been plenty of government scandals in American history—it has struck a reasonable balance between judicial oversight and the need to give the government appropriate leeway in carrying out its functions.

The presumption also directly protects the judiciary. By presuming regularity, courts can often avoid direct, politically charged confrontations with the executive branch that they might, as the “least dangerous” branch, ultimately lose. It’s an example of what the legal scholar Alexander Bickel called the “passive virtues”: the courts’ use of doctrines of restraint (such as deference) to preserve their institutional capital.

The Presumption of Regularity Under Trump

The presumption of regularity faced significant strain during the first Trump administration. Most notably, multiple lower federal courts rejected the administration’s stated national security rationale for the travel ban targeting several Muslim-majority countries. The courts found evidence suggesting that the policy was driven by religious animus rather than legitimate security concerns and, therefore, declined to presume that the government had acted in good faith.

Courts questioned the presumption in smaller, one-off cases as well. For example, Judge Reggie Walton, citing “grave concerns” about then-Attorney General William Barr’s “lack of candor” regarding the Mueller report, ordered an in camera review of the unredacted report in a Freedom of Information Act case, explicitly refusing to accept the government’s representations about redactions due to concerns about its credibility and good faith.

For all the damage the first Trump administration did to the presumption, its conduct the second time around has been far worse. Just a few days into the new administration, Steve Vladeck noted how it seemed “inclined to upset (if not upend) [the Justice Department’s] longstanding relationship with the federal courts.” The administration’s actions over the past two and a half months have confirmed that prediction. In response, judges across the country, including many appointed by Republican presidents (and sometimes even by Trump himself), have frequently and openly questioned the administration’s factual assertions and stated motivations in court filings and hearings. Consider just a few high-profile examples of courts implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) finding that, despite the benefit of the doubt traditionally afforded by the presumption of regularity, the administration had not acted lawfully or in good faith:

- In litigation concerning deportations under the Alien Enemies Act, Judge James Boasberg accused the government of acting in “bad faith” when it failed to stop deportation flights despite his in-court order to do so. He stated there was a “fair likelihood” that the government violated his order and signaled that he may hold government officials in contempt. In response, President Trump called for Boasberg’s impeachment, calling him “Crooked” and a “Radical Left Lunatic” who, unlike Trump, “DIDN’T WIN ANYTHING.” This in turn prompted a rare public rebuke by Chief Justice John Roberts, who released a statement pointing out that “[f]or more than two centuries, it has been established that impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision.”

- In a fiery opinion enjoining the Trump administration’s attempt to block transgender people from serving in the military, Judge Ana Reyes described the ban as “soaked in animus and dripping with pretext.” She questioned the administration’s decision-making process behind the ban, writing, “No one knows what [Trump] relied on, if anything.” When, during the hearing about the ban, the Justice Department lawyer said, “I don’t have an answer” to Reyes’s question about whether the ban was motivated by animus, she shot back, “You do have an answer, you just don’t want to give it.” She also accused the government of trying to “say one thing in public and then come here to court and say something else entirely.” (The Justice Department, its feelings apparently hurt, has made a formal complaint against Judge Reyes with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.)

- Judge Beryl Howell, during a hearing on Trump’s targeting of the Perkins Coie law firm, said that the government’s argument “sends chills down my spine.” In issuing a temporary restraining order against the government, Howell compared Trump to the Queen of Hearts in “Alice in Wonderland,” noting that “[t]his may be amusing … where the Queen of Hearts yells, ‘Off with their heads!’ at annoying subjects and announces a sentence before a verdict. But this cannot be the reality we are living under.” After the government, in response to the hearing, moved to disqualify Howell from the case, she accused the Justice Department of engaging in “ad hominem attack” that was “designed to impugn the integrity of the federal judicial system.”

- Dismissing the indictment against New York City Mayor Eric Adams, Judge Dale E. Ho sharply criticized the Justice Department’s stated reasons for dropping the case. He found the rationale concerning “appearances of impropriety” and election interference “unsupported by any objective evidence” and likely “pretextual.” Regarding the claim that the prosecution hindered cooperation on immigration policy, Ho stated, “Everything here smacks of a bargain: dismissal of the Indictment in exchange for immigration policy concessions,” calling this rationale “unprecedented and breathtaking in its sweep” and “fundamentally incompatible with the basic promise of equal justice under law.” While acknowledging his inability to force the prosecution, Ho dismissed the case with prejudice specifically to prevent the perception that the mayor’s “freedom depends on his ability to carry out the immigration enforcement priorities of the administration.”

- In litigation over the Environmental Protection Agency’s termination of $20 billion in climate grants, Judge Tanya Chutkan repeatedly pressed the administration for proof supporting its public allegations of criminality and fraud. Finding the government unable to provide evidence weeks into the case—“Here we are, weeks in, and you’re still unable to proffer me any information with regard to any kind of investigation or malfeasance,” she said—Chutkan questioned the lawfulness of the termination and temporarily blocked the return of funds. This judicial skepticism unfolded amid reports that a senior assistant U.S. attorney resigned rather than execute a related criminal seizure order and that a magistrate judge refused to authorize it.

- In litigation challenging the Trump administration’s attempt to dismantle the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Judge Amy Berman Jackson granted a preliminary injunction, finding the administration’s arguments lacked credibility. She specifically called out the government’s shifting explanation for a “stop work” order issued to agency staff, stating that its “eleventh hour attempt to suggest immediately before the hearing that the stop work order was not really a stop work order at all was so disingenuous that the Court is left with little confidence that the defense can be trusted to tell the truth about anything.”

- Judges across the country are growing exasperated with government counsel who are unable to answer basic factual questions or who refuse to confirm whether the government has complied with court orders. One judge described it as “suspicious” that the government lawyer could not answer the question of who was the first head of the Department of Government Efficiency. Another asked why they were unable to “get a straight answer” from the government lawyer as to whether their order unfreezing U.S. Agency for International Development funds had been followed.

Beyond the individual cases, the Trump administration’s actions more generally undermine the presumption of regularity. Judges, after all, are people too. They read the news just like the rest of us.

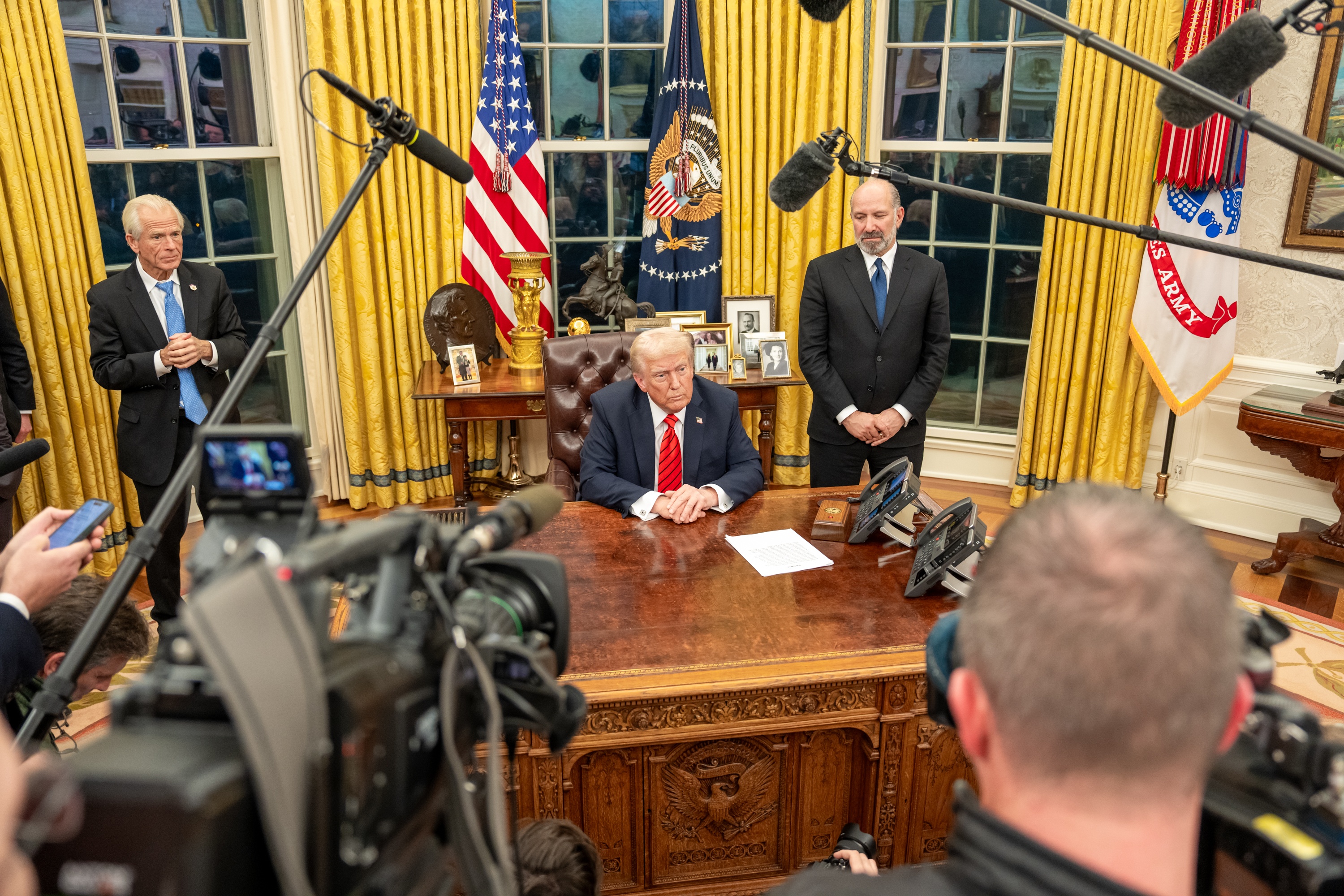

Consider a judge who, in the past 12 weeks, has lived through the following: visas being revoked based on political speech; the crippling of vast swaths of the federal government; a push to end birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented migrants; escalating attacks on research universities; public musings by the president about seeking an unconstitutional third term; self-dealing at the highest levels of government; the open refusal to enforce federal law despite congressional passage and judicial approval; blocking money to states based on governors acting “disrespectfully”; mishandling of classified war plans; the appointment of unqualified partisans to high-level government positions; the dismissal of national security officials based on complaints from a conspiracy theorist; the humiliation of a beleaguered ally in a public Oval Office broadcast; and the deliberate upending of the global trading system that has sent markets reeling. And this is just the past three months. It doesn’t include Trump’s first term actions, culminating in his attempt to overthrow the 2020 election and his various criminal convictions and indictments in the intervening years.

You don’t have to be what the president would call a “certified Trump hater” to question whether this administration is playing it straight, not just in litigation, but in general.

Consequences of a Collapsed Presumption

A world in which the government’s actions undermine its claims to a presumption of regularity would have profound consequences.

First, it would put intense strain on the adversarial nature of the legal system. Unlike inquisitorial systems, in which judges actively engage in fact-finding, our system relies heavily on opposing counsel to present their cases vigorously and truthfully. This presupposes a baseline of good faith and candor from all lawyers, particularly those representing the government. When that baseline disappears, the system struggles to function effectively. Courts may feel compelled to adopt more inquisitorial methods, demanding independent evidence and verification even for routine government assertions. This shift toward judicial fact-finding requires more judicial time and resources and courts are ill-equipped for it, having limited investigative resources—perhaps a judicial assistant and a few law clerks—compared to the extensive staff required in a truly inquisitorial system. Moreover, such heightened scrutiny could unduly hinder legitimate, necessary, and time-sensitive government functions, creating inefficiencies and potentially chilling lawful executive action.

Second, the collapse of the presumption will have, if it hasn’t already, a corrosive internal effect on the government itself, particularly on the Department of Justice and its lawyers. When an administration demands actions or advances legal positions based on questionable factual assertions or pretextual rationales, it forces government lawyers into a difficult position. This pressure is amplified when leadership signals, as Attorney General Bondi did when she described Justice Department staff as “his”—that is, Trump’s—“lawyers,” that loyalty to the executive’s agenda is prioritized over traditional duties to the court and the law. Although their primary ethical duty as officers of the court mandates candor, acting on this duty can place them in direct opposition to the administration’s wishes. This creates a sharp conflict—not of ethics, as the duty of candor is paramount, but of practical consequence, pitting professional obligations against employment repercussions, including outright firing.

This dilemma can drive experienced, ethical lawyers out of public service, thus eroding institutional integrity, expertise, and capacity within the Justice Department. This degradation, in turn, leads to less effective government representation and more errors or questionable conduct before the courts, creating a negative feedback loop that further diminishes judicial trust and undermines the presumption, ultimately hindering the government’s ability to function effectively under law. Judges have already noticed the degraded nature of Justice Department representation—both in terms of the fewer government lawyers available and the increasing reliance on political, rather than career, officials. For example, in a hearing over the administration’s targeting of the law firm Jenner & Block, Judge John Bates asked Richard Lawson—the sole government lawyer present, who had been hired by Attorney General Bondi after previously working for her on consumer protection matters in Florida—why he was the lawyer on the case: “The Department of Justice has a lot of lawyers. Why is this all on you, Mr. Lawson?”

And third, if courts are unable to apply the presumption, it could weaken the judiciary, in both the short and long terms. Courts possess neither the “purse” nor the “sword”; their authority rests significantly on their perceived legitimacy and the willingness of other branches to respect their judgments. If courts frequently call out government falsehoods or bad faith, and the executive branch ignores or dismisses these findings, the judiciary’s authority is diminished. This risks escalating confrontations that the judiciary is ill-equipped to win, potentially leading to constitutional crises where the rule-of-law outcome—mass public mobilization that causes the executive to back down—is far from guaranteed. Conversely, if the judiciary fails to call out blatant government falsehoods, it risks losing credibility with the public. It’s a no-win situation for the courts.

A more profound long-term risk is that an executive, frustrated by judicial checks, might seek to undermine the courts’ independence by altering their composition—a tactic common in authoritarian regimes worldwide. During his first term, President Trump’s judicial nominations, although sometimes controversial, drew largely from established conservative legal circles, effectively outsourcing selections to groups such as the Federalist Society. But subsequent fallings-out with these groups, coupled with judicial defeats—including at the hands of his own appointees—in challenges to the 2020 election, appear to have taught Trump a different lesson: that personal loyalty is the paramount, perhaps sole, judicial virtue.

While there have not yet been any judicial nominations in this second term, the personnel choices for top law enforcement roles signal a clear prioritization of allegiance over traditional qualifications or independence. Consider Trump’s attempt to appoint Matt Gaetz as attorney general, alongside the successful appointments of Bondi as attorney general, his personal lawyers Todd Blanche and D. John Sauer to top positions at the Justice Department, and Kash Patel and Dan Bongino to head the FBI. If future judicial nominations follow the same loyalty-first criterion, they might make a judge like Aileen Cannon—whom Trump has described as a “model of what a judge should be”—look like Sir Thomas More by comparison.

What Now?

Given the damage observed, what are the potential future trajectories for the presumption of regularity?

One potential path forward involves the administration acknowledging the institutional damage caused by its loss of credibility with the courts and taking concrete steps to rebuild trust through consistent good-faith conduct and truthful representations. This would be the response of any normal administration, where even a fraction of the pushback that government lawyers are getting from judges would prompt a full-blown panic at the Justice Department. Suffice it to say, this is not a normal administration, and there’s little reason to think that self-correction is in the cards.

Another possibility is that the presumption of regularity is well and truly broken, at least concerning the current administration. In this scenario, courts, their trust shattered, would operate with persistent (and justified) skepticism toward the executive branch. Judicial scrutiny of government actions and assertions would necessarily remain high, effectively shifting the burden to the government to affirmatively demonstrate its good faith, even in routine matters (with all of the drawbacks, described above, that such a change would entail). It’s hard to predict what such a world would look like, so radically would it deviate from settled constitutional practice. But like other foundational norms undermined by this administration, its loss would introduce profound instability and unpredictability, pushing the relationship between the courts and the executive into uncharted and dangerous territory.

The final—and most worrying—possibility is that, when the presumption of regularity reaches the Supreme Court, conservative justices could slap down skeptical trial judges, issuing rulings that effectively transform the presumption of regularity into a rule of mandatory deference, facts be damned. During the first Trump administration, the Supreme Court adopted this approach in at least some cases—most notably in Trump v. Hawaii, where the Court, in an opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts, explicitly disregarded the evident anti-Muslim animus behind the administration’s multiple travel bans (although, in other cases, the Court was willing to look beyond the presumption and find evidence of bad faith in administration actions).

Worryingly, early signs suggest that the Supreme Court is heading in this direction. Earlier this week, the Court provided a stark example when, in a 5-4 decision, the majority vacated a lower court’s restraining order that had blocked the administration’s legally dubious use of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act for mass deportations. While affirming basic due process rights in theory, it undermined them in practice by requiring that challenges proceed via individual habeas corpus petitions in the district of confinement rather than through broader class litigation in D.C. As Mark Joseph Stern observed in Slate, “The majority seems to be affording the president a strong presumption of regularity—assuming good faith and respect for constitutional boundaries.” In other words, as Vladeck writes, they’re “burying their heads in the sand.”

The justices aren’t fools. They understand the administration they’re dealing with, one in which the president and his hand-picked subordinates lack the necessary virtues of high office. They may think that it’s better to go along with a lawless executive rather than face defiance and potential irrelevance. But it is better to fail with honor than be complicit in lawlessness.