What Happens When We Don’t Believe the President’s Oath?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

i

The Constitution’s eligibility requirements for the presidency are spare, and in every formal sense, at least, Donald J. Trump meets them all: He was elected with a majority of electoral votes in a fashion that comports with the Twelfth Amendment. While he famously questioned his predecessor’s birth certificate and citizenship, nobody seems to doubt his. Trump is, as Article II, Section I, Clause 5 requires, “a natural born citizen”; he has “attained to the age of thirty five years”—with some years to spare, actually; and he has certainly “been fourteen Years a resident within the United States.”

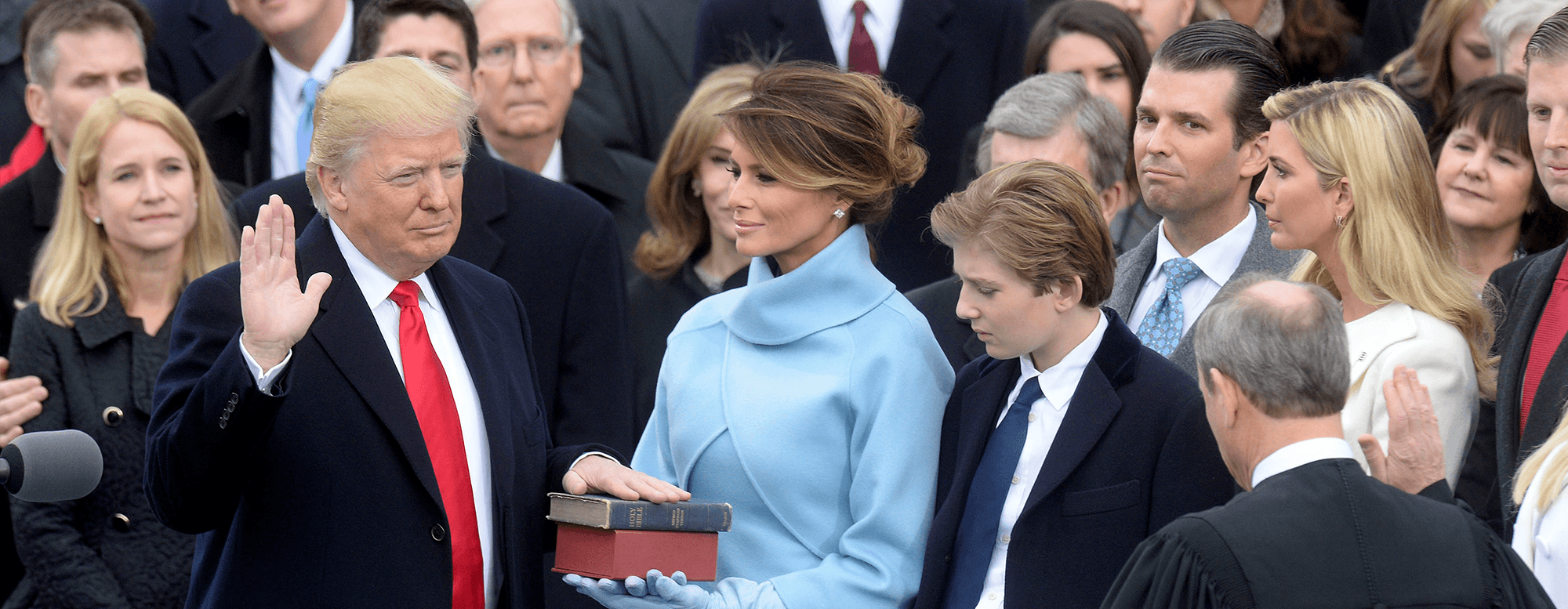

And finally, on January 20, 2017, in apparent accordance with Article II, Section I, Clause 8, “Before he enter[ed] on the execution of his office, he [took] the following oath or affirmation:—‘I do solemnly swear . . . that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.’”

There’s only one problem with Trump’s eligibility for the office he now holds: The idea of Trump’s swearing this or any other oath “solemnly” is, not to put too fine a point on it, laughable—as more fundamentally is any promise on his part to “faithfully” execute this or any other commitment that involves the centrality of anyone or anything other than himself.

![]()

Indeed, a person who pauses to think about the matter has good reason to doubt the sincerity of Trump’s oath of office, or even his capacity to swear an oath sincerely at all. We submit that huge numbers of people—including important actors in our constitutional system—have not even paused to consider it; they are instinctively leery of Trump’s oath and are now behaving accordingly.

This reality, and we argue here that it is a reality, is already conditioning the Trump presidency in overt ways visible every day. What’s more, we submit that these doubts about the President’s oath will inevitably shape public and institutional reaction to his service. And as a predictive matter, we believe that doubts about the President’s oath will have important and negative implications for the future of the American presidency.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that the sincerity of the presidential oath presents any sort of justiciable question. To the contrary, what makes the problem of Trump’s oath vexing and difficult is precisely that it is quite improper for the judiciary to look behind a person’s formal compliance with Article II, Section I, Clause 8—any more than the courts have mechanisms to verify that the content of a State of the Union address really meets the requirements of Article II, Section 3. It's the very definition of a political question.

Rather, our argument is both subtler and, in some respects, more dramatic: It is that the presidential oath is actually the glue that holds together many of our system’s functional assumptions about the presidency and the institutional reactions to it among actors from judges to bureaucrats to the press. When large enough numbers of people within these systems doubt a president’s oath, those assumptions cease operating. They do so without anyone’s ever announcing, let alone ruling from the bench, that the President didn’t satisfy the Presidential Oath Clause and thus is not really president. They just stop working—or they work a lot less well.

That is, we argue here, what we’re seeing now. And the disruption in our expectations of the presidency, and our civic and legal responses to it will, we suspect, have a very long tail.

ii

The day after the election, one of us wrote the following about his posture towards the new President-elect and the way he personally intended to cover Trump’s administration on Lawfare:

Trump’s election will fundamentally change my work on this site over the next few years, and probably off the site too. Because at least for me, Trump does not enter office with a presumption of regularity in his work. He does not enter office with a presumption that as President he will pursue a vision of what national security means that is remotely related to my own or that he will do so in a rational fashion—or even that he and I share a common idea of what aspects of this nation we are trying to secure.

The sentiment received a fair bit of criticism from people who thought that no president deserved such a presumption:

This is the skepticism that citizens, and especially journalists, should apply to *all* Presidents. But either way, welcome @benjaminwittes! https://t.co/DkcR5zEz1n

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) November 10, 2016

Is Trump really different from any other president? Why would an analyst attach a presumption of regularity to the conduct of a president in the first place?

There’s a big, if somewhat ineffable, difference between opposing a president and not believing his oath of office. All presidents face opposition, some of it passionate, extreme, and delegitimizing. All presidents face questions about their motives and integrity. Hating the President is a very old tradition, and many presidents face at least some suggestion that their oaths do not count. Obama, after all, was a foreign-born Muslim to his most extreme detractors.

Yet, for a variety of reasons we discuss below, there is something different about the questions about Trump’s oath, and it is how widespread and mainstream the anxiety is. It’s also, and we want to be frank about this, how reasonable the anxiety is when applied to a man whose word one cannot take at face value on the pre-political trust the oath represents. That person does not get certain presumptions our system normally attaches to presidential conduct.

If you’re a liberal, one who voted against George W. Bush twice, do the following thought experiment: Did you ever doubt, even as you decried the Iraq War and demanded accountability for counterterrorism policies and actions you regarded as lawless, that Bush was acting sincerely in the best interests of the country as he understood them? Yes, people used the slogan “Bush Lied, People Died,” but how many of them actually in their hearts doubted that Bush was earnestly trying to do his duty by the electorate, even if they differed in their understandings of what that duty entailed? Some, to be sure, we suspect many more accepted that Bush was honestly doing his best.

One of those people, notably, was Barack Obama. Over the summer, on Face the Nation, he answered a question about his predecessor by saying, “first of all, George W. Bush, despite obviously very different political philosophies, is a really good man.”

Now ask: Would you answer this question the same way about Trump as you would about Bush—and do you think Obama would?

Conversely, if you’re a conservative who voted against Obama, do the same thought experiment in reverse: Did you ever doubt, even as you decried Obamacare and fumed that Obama was weakening America, that he was acting sincerely in the best interests of the country as he understood them? Did you ever doubt that he was earnestly trying to do his duty by the electorate? And would you answer this question the same way about Trump?

Bush’s own reaction to his successors is instructive here. Bush notably chose to remain largely silent about Obama. And he explicitly tied this reticence to his respect for Obama’s presidency. In a 2009 speech, he said, “I love my country more than I love politics,” memorably adding: “He deserves my silence.”

The mutual respect between Bush and Obama is not simply the cordiality of two establishmentarians who are both part of the Presidents Club, though that may be part of the story. It is, we believe, the cordiality of two people who respect one another’s good faith—that is, who respect one another’s oaths of office.

And it stands in sharp contrast to the deference Bush has not shown to Trump. Over the last week alone, Bush has given two interviews containing barely disguised criticisms of the 45th president. On the Today show, he emphasized the role of an independent press as “indispensable to democracy” (in obvious reference to Trump’s attacks on the media as “the enemy of the people”), answered a question on Trump’s travel ban on refugees and immigrants from seven majority-Muslim countries by saying that “a bedrock of our freedom is the right to worship freely,” and indicated support for an investigation into connections between the Trump administration and campaign and the Kremlin. In People magazine, he said of the mood under the new administration, “I don’t like the racism and I don’t like the name-calling and I don’t like the people feeling alienated.”

There’s actually a good reason, lots of good reasons, why people react differently to Trump—why, that is, they don’t merely oppose him politically but seem to doubt whether he’s earnestly committed to trying to the best of his ability to do right by the country.

To be sure, the doubt is by no means universal. As we write this, 43 percent of Americans approve of the president’s performance so far—an unusually low figure for a new president but nevertheless a significant portion of the country. Presumably, citizens who approve of Trump also believe in the integrity of his oath of office.

But that leaves a huge number of people who are harboring doubts. And the doubts are not limited to the fringe. On the contrary, the belief that there is something different about this president is extraordinarily common among sober commentators of both the left and right—and, even more notably, among many of those with significant experience in government in both career and political roles.

So why the doubts? For one thing, Trump’s highly erratic statements and behavior include any number of incidents that seem to reflect a lack of understanding of his office or its weight. It’s not just the tweets. This is a person, after all, who suggested before the election that he might not even serve as president if he prevailed; who then said that he would accept the results of the election “if I win”; who made up a whole lot of voter fraud; who promised to prosecute his opponent; who, in his first public address following the inauguration, stood in front of the CIA’s Memorial Wall and bragged falsely about the number of people who attended his inaugural ceremony; who has made use of the immense power of the bully pulpit to publicly complain about the “unfair” decision by a private retail company to drop his daughter’s fashion line; who approached the process of selecting a Secretary of State, National Security Advisor, and nominee to the Supreme Court in a manner more fit for reality television than the office of the presidency; who refused to accept responsibility for the death of a Navy SEAL in a botched counterterrorism raid conducted on his orders, claiming instead that “this was something they [the generals] wanted to do,” before standing in front of Congress and apparently ad-libbing that the SEAL was looking down with happiness from Heaven because Trump received extended applause during his address; and whose most memorable quotation coming out of the presidential campaign was the inimitable, “Grab ‘em by the pussy”—a phrase he then dismissed as “locker room talk.”

Moral seriousness and respect for his office just isn’t his thing.

This is also a person whose campaign was rife with promises to commit crimes and to abuse the powers of the very office for which he then took the oath.

The combination of the sprawling nature of his business and the intentional obscurity of his finances is also a factor. A person who takes an oath yet maintains financial entanglements that create potential conflicts of interests—conflicts he refuses to acknowledge—and who shrouds the entire affair in a secrecy far in excess of predecessors whose finances presented far less complexity invites doubt. He invites questions about what else, other than his oath, may be guiding his behavior. This is particularly true when the financial relationship coexist with his bizarre solicitude for Russia—with which several of his aides have maintained financial and political relationships and regarding which rumors have swirled about his own ties. One doesn’t have to be a conspiracy theorist, given these circumstances, to ask the question about Trump’s oath: What else is going on here?

Then there’s Trump’s strange and adversarial relationship with the truth—a matter about which one of us has written at length. While Trump produces a stream of obvious and easily falsifiable fabrications—and the Washington Post keeps a convenient tally of presidential lies since his inauguration, a tally which currently stands at 190—the President is less of a liar than a bullshitter, in the sense described by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt. A bullshitter in this technical sense is a person who does not aim to obscure the truth so much as operates without any relationship to truth whatsoever. The liar, Frankfurt says, must have some knowledge of the facts at hand, in order to conceal them. But to the bullshitter, facts are nothing more than an irrelevance.

In Frankfurt’s argument, this is what makes bullshit dangerous: the liar makes the key concession that “there are indeed facts that are in some way determinable or knowable.” Bullshit, on the other hand, glibly rejects the value and even existence of knowable facts.

Trump’s bullshit raised questions of its own when he was in the running for the presidency. But now that he has sworn the oath of office, we are forced to confront what it means for a bullshitter to have promised to faithfully execute the office of President and to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States and the country’s larger legal system. Bullshit, after all, is kind of the opposite of law, which is an organized system of meaning.

There is a related concern about the Take Care Clause, which—echoing the oath’s requirement that the president “faithfully execute” the duties of the office—mandates that the president “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Can a bullshitter, whose entire method of engaging with the world is incompatible with the concept of fidelity and whose fundamental slipperiness and laxity in shouldering responsibility makes impossible the notion of “taking care,” really fulfill the requirements of this clause? But the Take Care Clause presentation of the problem necessarily presents the question in its specific, as-applied sense: Did the president take care in a particular instance that the law was faithfully executed? The oath presents the concern in general.

It makes us ask: What does it even mean for a person who contradicts himself constantly, who says all kinds of crazy things, who has unknown but extensive financial dealings that could be affected by his actions, and who makes up facts as needed in the moment to swear an oath to faithfully execute the office?

iii

The Presidential Oath Clause is not, shall we say, one of the Constitution’s rock stars. The Federalist Papers barely mention it. It doesn’t have a particularly extensive academic literature. No famous Supreme Court cases overtly turn on it or interpret it. An admittedly unscientific but nonetheless illustrative Twitter survey suggests that discussion of the oath is not dominating constitutional law classes either: Among 1,203 respondents, 90 percent recalled either no discussion (70 percent) of the oath in their classes or only a “brief mention” (20 percent); only three percent recalled “lots” of oath talk.

Question for people who have taken a Con Law class: How much discussion did you have of the presidential oath clause of the Constitution?

— Benjamin Wittes (@benjaminwittes) February 26, 2017

The presidential oath was introduced into the Constitution by one John Rutledge, who would later become the second Chief Justice of the United States. In its initial form, the oath read briefly: “I solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States of America.” The Convention then added a second clause (“will to the best of my judgement and power, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States”), following a proposal by George Mason and James Madison.

The oath was then tweaked to replace “judgement and power” with “abilities and power,” and then to replace that with simply “ability.”

Amidst these revisions, James Wilson—who would soon be appointed to the Supreme Court by George Washington—objected that the provision for a separate presidential oath was redundant given the Constitution’s preexisting requirement that government officials all swear an oath. Notably, while this clause—listed in Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution—requires that “all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution,” the Constitution leaves it up to Congress to determine the oath itself. Wilson’s objection did not carry the day, however, and the result is the anomaly that the text of the presidential oath of office, but no other, is spelled out in the Constitution itself.

The oath makes only scant appearances in Supreme Court case law, and figures not at all in most of the seminal cases involving the scope of presidential power.

But don’t let that fool you. It is actually a fundamental underpinning not only of many of our cultural assumptions regarding presidential behavior, but also of the judiciary’s willingness to grant deference to the executive branch, particularly in the realm of national security. This point is actually not limited to the presidency. Oaths of office are, more generally, a foundational component of inter-branch deference and comity. When the courts presume a statute constitutional, they do so because it was passed by a coordinate branch of government whose members swore oaths to protect the Constitution. The presumption of constitutionality is, in other words, a deference to the institution of a coordinate branch as populated by people who swear oaths to the Constitution. Similarly, when the courts presume regularity in executive behavior or defer to the executive branch on a matter entrusted to it, the source of the presumption is that the office-holder has sworn an oath too.

To understand the relationship between the oath and the deference to the president in national security matters, start with Joseph Story. In Commentaries on the Constitution, Story wrote of the oath of office generally:

Oaths have a solemn obligation upon the minds of all reflecting men.... If, in the ordinary administration of justice in cases of private rights, or personal claims, oaths are required of those, who try, as well as of those, who give testimony, to guard against malice, falsehood, and evasion, surely like guards ought to be interposed in the administration of high public trusts, and especially in such, as may concern the welfare and safety of the whole community.

Of the presidential oath particularly he said:

No man can well doubt the propriety of placing a president of the United States under the most solemn obligations to preserve, protect, and defend the constitution. It is a suitable pledge of his fidelity and responsibility to his country; and creates upon his conscience a deep sense of duty, by an appeal at once in the presence of God and man to the most sacred and solemn sanctions, which can operate upon the human mind.

Once a government official, and particularly a president, swears the oath of office, in other words, we assume that the oath binds the person to a certain degree of public virtue and good faith, along with inculcating a sense of duty and responsibility. That is something we can defer to.

For a practical example of this idea in the national security litigation space, consider the controversial 2011 Guantanamo habeas case in the D.C. Circuit, Latif v. Obama, which turned on the question of whether an intelligence report of uncertain reliability was due a “presumption of regularity.” Writing for the court, Judge Janice Rogers Brown held that the report could be presumed to be a reliable record of Latif’s statements on the grounds that, “in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, courts presume that [public officers] have properly discharged their official duties.” This “presumption of regularity,” Brown wrote, “is founded on inter-branch and inter-governmental comity.”

In other words, the presumption of regularity follows from the “common experience” that “public officials usually do their duty,” as Judge Karen LeCraft Henderson wrote in her concurring opinion in the case. And this “common experience” derives from the fact that, in doing their duty, public officials are honoring their oaths.

Follow the line of cases cited in Latif and you’ll quickly arrive at the 1827 case of Martin v. Mott, which the D.C. Circuit cited in American Federation of Government Employees v. Reagan as the source of the presumption. In Mott, the Supreme Court held (regarding the reviewability of the president’s decision to call up the militia) that, “Every public officer is presumed to act in obedience to his duty until the contrary is shown.” While the Court acknowledged the potential danger of deferring to the executive on a militia muster, it wrote that mitigating this concern are “the high qualities which the Executive must be presumed to possess, of public virtue, and honest devotion to the public interests.”

Chief Justice Roger Taney made a similar point some twenty years later in Luther v. Borden. Citing Mott, the Court declared nonjusticiable the question of whether President John Tyler had, after recognizing Rhode Island’s incumbent government as legitimate over the rebel government during the Dorr War, rightly made the determination to support the state’s Charter Government in calling up the militia. Despite the potential for abuse of the presidential power to muster the militia, the Court held: “[T]he elevated office of the President, chosen as he is by the people of the United States, and the high responsibility he could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment, appear to furnish as strong safeguards against a wilful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide.”

In both Mott and Luther, in other words, the Court argues that it owes the president deference because it must trust in his presidential virtue. This trust in the president’s moral fiber and his (or her) sense of public responsibility derives not from a personal regard for the individual who happens to be president. It derives, rather, from the fact that he or she has been elected by the people, and that the deference is thus to the popular will, and also from the fact that his or her election was—as Story describes—subsequently solemnized by his oath of office.

There’s even a school of thought that the oath of office is a critical foundation for inherent presidential powers. Dissenting in Youngstown, Chief Justice Fred Vinson cites the Presidential Oath Clause in conjunction with Alexander Hamilton’s description of “Energy in the Executive” in Federalist 70 as evidence that “the Presidency was deliberately fashioned as an office of power and independence”—which, he argues, grants the president expansive powers in a time of emergency. Likewise, the Court in U.S. vs. U.S. District Court (Keith) notes that “implicit in that duty [to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution under the oath of office] is the power to protect our Government against those who would subvert or overthrow it by unlawful means.” And according to Justice Lucius Lamar’s dissent in In re Neagle—another case involving questions of inherent presidential powers—the government argued before the Court that the presidential oath “by necessary implication … invest[s] the President with self-executing powers … independent of statute.” (Unlike his brethren, Lamar did not find this argument convincing.)

Our point here isn’t exhaustively to trace the history of the oath or its relationship to comity and deference; it’s merely to point out that a lot actually turns on the oath, especially in areas in which the president asks for deference from other actors. And it follows that when a president’s oath is reasonably subject to question, the system frays and those systems of deference stop working.

iv

So what does it look like when large numbers of people do not trust the President’s oath and, as a consequence, do not believe he “enter[s] office with a presumption of regularity in his work”? It looks something like what we’re seeing now, in which a wide array of actors simply do not afford deference to presidential actions and words.

Let’s start with the courts. There’s much to argue about in the astonishing flood of judicial opinions that followed Trump’s issuance of his executive order on visas and refugees. For present purposes, the only point is that a very large number of judges around the country behaved in a fashion untouched by deference or any kind of presumption of regularity in the President’s behavior: by our count, at least eight district courts and one circuit court have issued stays or temporary restraining orders against the executive order. Note that they did this in an area of broad statutory grants of power to the president in the face of a claim by the President that he was acting to protect national security. They intervened rapidly. And their lack of deference was, in some cases, proud.

The 9th Circuit, for example, took the opportunity of denying a government request for a stay to write an extended defense of the reviewability of presidential action in this area, citing a parade of blockbuster cases on executive power—including Ex parte Endo, Ex parte Quirin, and Boumediene—to assert that, “There is no precedent to support this claimed unreviewability, which runs contrary to the fundamental structure of our constitutional democracy.” Notably, along the way, the court didn’t even pause to cite the statute the executive order cites as its principal statutory basis. To be sure, some of this lack of deference flows from the astonishingly sloppy fashion in which the order was issued and the lack of evidence the president submitted in support of its necessity or reasonableness. But the two points are connected. Judges confronted by an executive whose oath they don’t trust will find that mistrust dramatically enhanced by a failure to produce a record that warrants deference.

The judicial response to the executive order has been both lauded as heroic and derided as lawless grandstanding. Our point is more sociological: This is the way judges behave when they do not believe, with the Court in Mott, that the president “is presumed to act in obedience to his duty until the contrary is shown” and when they do not presume with the Court in Luther that “the high responsibility [the president] could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment, appear[s] to furnish as strong safeguards against a wilful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide.” This is how courts behave when they cannot begin with the premise Obama began with about Bush: that the president is a good man.

A similar instinct lies, we believe, behind the unprecedented barrage of leaks that has plagued the Trump administration since the day the new president took office. Even Lawfare, which has never before published leaks, has received and published leaked information from government officials uncomfortable with the administration’s policies. Leakers have released drafts of executive orders, along with a draft Department of Homeland Security intelligence report contradicting the administration’s claims on the critical necessity of the travel ban to national security. They have given reporters personal and embarrassing details on the president’s mental state, and have continued to inform the press on the classified details of the Russia Connection as investigations into election interference by the Kremlin and the Trump campaign’s contact with Russian officials unfold—to the dismay of the President, who has called for an investigation into the leaking and insisted that information being leaked is “fake news.”

All this culminated rather comically in a recent State Department memo by acting legal advisor Richard Visek condemning leaks and advocating that department employees instead make use of State’s internal dissent channel—a memo which itself promptly leaked to the press. Similarly, when press secretary Sean Spicer demanded to examine the phones of White House staffers to check for leaking and ordered staffers not to speak to the press about the meeting, Politico quickly got hold of the story.

The vertical integration of the executive branch depends pervasively on the President’s oath. If a judge does not believe in the integrity of that oath, she may show less deference than she otherwise would—or than doctrine might insist is proper in the circumstances. But if a staffer in a federal agency doesn’t believe in the integrity of the president’s oath, that mistrust breaks key bonds that tie that staffer to the executive will. After all, the reason to follow orders in the executive branch is that the president is both elected by the people, and thus represents the popular will, and has sworn an oath to faithfully execute the laws. If you don’t believe that oath and you don’t believe that he is necessarily pursuing the public’s interest, why follow orders and carry out his policy? Such a staffer may feel no compunction about telling someone in the press about policy discussions he doesn’t believe are being undertaken in a sincere effort to “faithfully execute” the functions of the executive branch and to “preserve, protect and defend” the Constitution. He may actively believe that his own oath of office requires a certain degree of undermining of those policy processes, both with forms of internal pushback and resistance and with public exposure. Or, less nobly, he may simply feel freed from normal bonds of loyalty and hierarchical discipline and thus able to embarrass a hated boss or scuttle policy changes he doesn’t like.

The point is simply that when the bureaucracy doubts the president’s oath, that fact gravely frays the executive’s ordinary comparative unity. The people who work for the president no longer connect loyalty to the executive branch with the lofty goals to which the oath seeks to bind the president, so they become much more likely to act on their own.

Finally, you can see doubts about the integrity of Trump’s oath in the press’s reaction to him. A normal presidency always involves a certain degree of factual jockeying with the press. Presidents say things that turn out not to be true, and the press tends to harp on these things. Some presidents have lied very fatefully and famously. That said, there is a presumption of regularity even on the part of the press in hearing presidential statements. When Obama or Bush or even Bill Clinton—at least on issues not touching Clinton’s personal probity—would make a public statement on a factual matter, the press had a working assumption that it was not, to use Frankfurt’s term, bullshit.

As former Bush speechwriter David Frum put it recently,

When I worked for President Bush, we had a staff of researchers, and we would go through any document—every name had to be double-checked, every place, every statistic we used was checked—because we thought it would be really a big deal if we said, “Industrial production in Michigan was 6.2 percent in the last quarter,” and the real number was 5.9. Heads would roll. Things would happen. And Donald Trump has proven that that’s not really true, actually, that there aren’t consequences for that kind of mistake.

But actually, that’s not quite right. There are consequences. One of them is that the press no longer presumes that any presidential statement is true. It gleefully corrects errors and misstatements. It has no compunction about alleging that such errors are active lies. And major press figures seem to have little reservation about overtly political comments about Trump and the administration. For example, CNN anchor Jake Tapper actually went so far as to call Trump’s comments about the press “un-American.” The Washington Post and the New York Times have both recently rolled out campaigns emphasizing their adversarial role to the administration, with the Post unveiling a new slogan below its masthead that reads, “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” and the Times launching an ad blitz emphasizing the paper’s dogged pursuit of truth amidst a flood of lies.

Trump has called the press the opposition party; he’s not entirely wrong.

Our point is not to either praise or condemn such press action. It is merely to observe that this is what happens when the press ceases to attach a presumption of regularity and good faith to presidential actions and statements. It’s what happens when large number of people in the press cannot start with the presumption that the president is making a good faith effort to do his job. It’s what happens when the press doesn’t merely question the president’s policies and seek to expose his administration’s foibles and errors and secrets, but actively doubts his oath of office.

v

It is too early, at this stage, to venture any kind of prediction of where the oath-free or oath-lite presidency of Donald Trump is taking us. But we should at least consider the possibility that it is the beginning of a profound institutional change to the presidency and our expectations of it. Imagine a world in which other actors have no expectation of civic virtue from the President and thus no concept of deference to him. Imagine a world in which the words of the President are not presumed to carry any weight. Imagine a world in which far more judicial review of presidential conduct is de novo, and in which the executive has to find highly coercive means of enforcing message discipline on its staff because it can’t depend on loyalty. That’s a very different presidency than the one we have come to expect.

It’s actually a presidency without the principle that we separate the man from the office. It’s a presidency in which we owe nothing to the office institutionally and make individual decisions about how to interact with it based on how much we trust, like, or hate its occupant.

Another possibility is that we will see something of a reversion to the mean. The ferocious reaction Trump has received from people and actors who doubt his oath may, over time, constitute a powerful insistence on the importance of a presidency in which the oath matters—and the importance as well of a presidency in which the oath is seen to matter. The result might be that the next president will be exceedingly careful to comport him- or herself in a fashion that provides a basis for deference from other actors and a presumption of regularity in presidential conduct and statements. Perhaps just as Nixon provided a negative template for presidential abuse against which all subsequent presidents have had to model themselves, Trump will model by negative example the fidelity of future presidents to their oaths.

Still a third possibility is some combination of the two—a reversion to the mean but with lasting damage to certain norms and expectations that have developed around the presidency. Because even if the next president and the ones after that strive to behave in an always exemplary fashion with respect to their oath, we will still have this memory of Trump’s proof of concept of an oathless presidency. We will still know that Chief Justice Taney was actually wrong when he wrote that “the elevated office of the President, chosen as he is by the people of the United States” necessarily instills a “high responsibility [its occupant] could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment.” And we will remember that the court in Mott was at least a little naive when it wrote of “the high qualities which the Executive must be presumed to possess, of public virtue, and honest devotion to the public interests.”

That memory, we suspect, will haunt the presidency for a long time to come.

.jpeg?sfvrsn=ad4bd1de_5)