What Hard National Security Choices Would a Biden Administration Face?

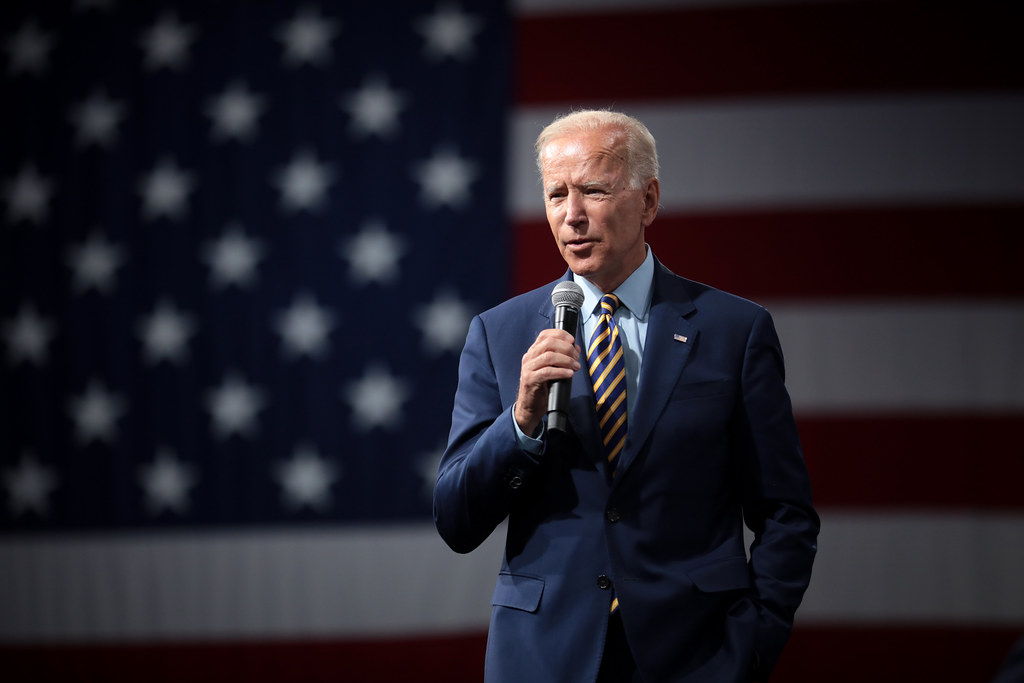

If Joe Biden wins the November election, Americans will likely see a reversion to a more traditional approach to the presidency. What might that mean in the field of U.S. national security?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

No one can predict the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, but what should Americans expect if Joe Biden wins? In particular, and in keeping with Lawfare’s motto, what are the “hard national security choices” that would confront an incoming Biden administration? The election of a new president from a different political party than the incumbent administration, following an extremely unusual predecessor, presents an opportunity for systematic reevaluation of national security matters. It is worth asking, therefore, what we might see in terms of change and continuity if Biden wins, as compared to the Trump administration.

I have no inside information or connection to his campaign, but if Biden wins, I expect hard national security choices to arise in at least the following areas, each of which is discussed below: (1) intelligence requirements and priorities; (2) offensive cyber activity; (3) covert action; (4) the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA); (5) foreign investment and technology; (6) international agreements, organizations and relations; and (7) pandemics and continuity of operations and government. I would also expect a Biden administration to focus more broadly on several issues that fall under an additional heading: (8) apolitical intelligence and rule of law.

1. Intelligence Requirements and Priorities

When Vice President Biden left office in January 2017, intelligence community resources were still largely focused on counterterrorism (although the National Intelligence Strategies released in 2009 and 2014 certainly recognized the risk posed by nation-state adversaries). Today, the intelligence community operates in a “2+3” framework (sometimes also referred to as “4+1”) focused on Russia and China in the first instance, and then Iran, North Korea and violent extremists (that is, international terrorists). (See the National Intelligence Strategy document released in 2019.) Along with the shift toward nation-state adversaries has come an increasing focus on cyber issues (in part because cyber is a favored tool of nation-states), including misinformation and disinformation campaigns, election interference, and the like—as reflected in the January 2019 Worldwide Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community. (The 2020 worldwide assessment is not publicly available, following the White House’s rebuke last year of intelligence community leaders for making points that were inconsistent with the president’s stated views—a significant change in traditions going back to 1994, when the director of central intelligence would publicly brief and engage in Q&A with Congress.)

A Biden administration is likely to accept the 2+3 framework, and effectuate it as usual through the National Intelligence Priorities Framework (NIPF) and other processes. But more granular questions about intelligence priorities remain. (For a discussion of how intelligence collection priorities are set through the NIPF and other processes, see pages 5-6 of this publication from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.) There are at least three groups of such questions.

First, what new intelligence priorities have arisen during the Trump administration? Based on public statements, for example, it seems likely that the Trump administration has increased intelligence focus on the U.S. southern border, including as to immigration and importation of opioids. How, if at all, did the Trump administration characterize these issues as national security threats? What authorities—statutory or otherwise—were triggered or invoked as a result of that characterization, and how were they used (to collect information or otherwise)? If there was increased focus in these areas, which other areas received less attention from the intelligence community or other agencies?

Second, there is a series of questions about our principal nation-state adversaries. For example, have the president’s statements and other actions pertaining to Russia and Vladimir Putin affected the intelligence community’s collection and analysis against Russia? If the intelligence community were given a strong, clear presidential mandate to focus aggressively on election interference and related active measures by Russia and other adversaries, and held accountable through the National Security Council, could and would it do more? As to North Korea, is U.S. collection deep and persistent enough that the U.S. will know when Kim Jong Un dies or becomes disabled, and—when he dies—who is likely to succeed him? With respect to China, what is the recent history and current state of its espionage and technology theft from the U.S.; can it be deterred from further theft; is there a potential alignment of interests concerning stability in North Korea, and at what cost to other U.S. interests in the region, including in South Korea; and will China continue engaging in widespread misinformation and disinformation campaigns, particularly in light of attribution issues over the coronavirus? How close is Iran to building a nuclear weapon, and what has followed from the demise of the nuclear deal with Iran (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA) and the reimposition of sanctions, as well as apparently high levels of coronavirus infections?

Third, there are significant questions with respect to terrorism. Has the coronavirus made the U.S. more or less vulnerable to a terrorist attack, including a biological terrorist attack? Are terrorists taking note of the U.S. response to the coronavirus and making plans accordingly? (Consider this 2013 paper on the risks of bioterrorism.) Were too few or too many resources directed away from international terrorism in the aftermath of the collapse of the Islamic State caliphate, and what is to be done with the foreign fighters who remain in the Middle East?

And, finally, what can be done about white supremacist terrorism? The rise of purely domestic terrorism generally in this country—most notably, white supremacist terrorism—is today addressed as a problem of law enforcement and is therefore largely out of scope for the U.S. intelligence community. But the intelligence community will need to focus on international terrorist groups that support white supremacist and other forms of international terrorism. In April 2020, the State Department designated the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM) as a terrorist group, marking the “first time the United States has ever designated white supremacist terrorists.” The department explained, “Since 2015, the world has seen a surge in white supremacist terrorism. … The United States is not immune to this threat. We’ve seen attacks targeting people because of their race or religion in places like Pittsburgh, Poway, and El Paso.” This form of terrorism will surely be an enduring issue for the next administration.

2. Offensive Cyber Activity

If Biden wins the election, his transition team and new agency leadership will need to recognize that there has been significant change in the authorities, policies and operations involving offensive cyber activity. Legislatively, the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) expanded and streamlined authority in this area. For example, Section 1632 clarified that clandestine offensive military cyber operations are traditional military activity and, hence, are not subject to the special rules and procedures regulating covert action. The executive branch believes that the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) does not apply to otherwise-authorized, military cyber activity, and the Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision on the CFAA in Van Buren v. United States is unlikely to change that. In a speech from March 2020, the Defense Department’s general counsel made clear that, at least in the view of the Trump administration, both U.S. constitutional law and international law permit aggressive activity in this field, including with respect to election security. A Biden administration is likely to take similar legal positions.

As a matter of policy, National Security Presidential Memorandum 13 apparently delegated significant operational authority to the Defense Department and reduced the capacity of the interagency to engage in soft objections to offensive cyber operations (the document itself is not public, but it has been discussed and characterized publicly by government officials). The National Cyber Strategy and Defense Department Cyber Strategy, both released in 2018, reflect a similar approach: The latter document proposes a “defend forward” strategy that involves “leveraging our focus outward to stop threats before they reach their targets.” A Biden administration will need to understand all of the following policy issues in this area: the theoretical and practical distinctions between “defend forward” offensive cyber activity conducted for defensive purposes, and other forms of offensive cyber activity; exactly how much power to act now resides in military commanders; and how much interagency coordination is required before action can be taken. It might want to adjust protocols in favor of less delegation, particularly at the beginning of the administration when new officials are less aware of and comfortable with the precedents and understandings developed in the Trump administration. For the longer run, depending on what Biden administration officials find with respect to those precedents, it would not be surprising to see them adopt a similar approach to the Trump administration, at least as to the defensive aspects of “defend forward” policy.

Some of the operational impact resulting from the new legislation and policy is already publicly visible courtesy of Gen. Paul Nakasone, the National Security Agency (NSA) director and commander of U.S. Cyber Command. Testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee in February 2019, he described the work of his agency and command, including efforts by the Russia Small Group to secure the 2018 midterm elections. More recently, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle are demanding that NSA/Cyber Command and the Department of Homeland Security take similar action against hacking efforts related to the coronavirus. An incoming Biden administration will need to familiarize itself with the law, policy, and operational capabilities in the offensive cyber realm; conduct a careful review of cyber operations conducted during the preceding four years; and then quickly decide how to direct Nakasone and other leaders to proceed against what will almost surely be serious, ongoing and imminent cyber threats. See this video on Cyber Command’s 10th anniversary.

3. Covert Action

Although military cyber operations do not qualify as covert action, there may have been similarly significant changes during the Trump administration with respect to covert action as well. Covert action should serve foreign policy, rather than setting it, and so one would expect a Biden administration to conduct a zero-based review to ensure proper alignment between the two. That might require a short-term triage of covert action programs at the outset of the new administration to correct any extreme and obvious misalignment, followed by a more thorough review over time as the details of U.S. foreign policy come into focus.

4. FISA

A Biden administration will need to confront two big issues under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). First, of course, accuracy reform at the FBI, stemming from the Justice Department inspector general’s investigation into the FBI’s probe into Russian election interference, known as Crossfire Hurricane, and the inspector general’s initial memo on the broader audit of FISA accuracy—both of which found significant problems. In light of my role as amicus curiae in the FISA Court on FBI accuracy, I will limit myself to excerpts from the public brief I filed in January 2020 and the Lawfare post I wrote in December 2019, before my appointment, which together make clear that the issues with FISA are significant and enduring. (I am writing here solely in my individual and personal capacity, of course, not as an amicus or for other amici or the court.)

In the December 2019 Lawfare post, I opined that the FBI’s “errors in the FISA applications on Carter Page were significant and serious”; that they were “not, in my experience, the kind of errors you would expect to find in every case”; and that indeed “the closest case to Crossfire Hurricane that I can think of arose almost 20 years ago,” meaning that the failures in the Page case were the worst in a generation. I explained how the FBI’s conduct in Crossfire Hurricane was, in several specified ways, “not acceptable ... not acceptable ... not acceptable ... not acceptable [and] ... certainly not acceptable.” Anticipating the inspector general’s broader audit, which at that time was still pending but which later identified significant problems in several other FISA cases, I explained that “the most likely explanation for a pattern of FISA failures—if that is what the audit finds—will be cultural,” and that “more will be required” because “[e]nsuring accuracy and fidelity to facts and rules is not a one-and-done undertaking.”

I made similar points in my amicus brief in January, arguing that the various “[c]orrective Actions” being proposed by the FBI to address accuracy issues were “insufficient and must be expanded and improved in order to provide the required assurance [of accuracy] to the Court.” In particular, I identified a need for change in three main areas: improved FISA standards and procedures, expanded training, and broader audits and accuracy reviews. The FBI and the FISA Court later accepted many of these proposals for additional reforms.

Going forward, among the most significant issues for a possible Biden administration will be how to use field agents as FISA declarants, swearing the truth of information provided by the FBI to the FISA Court (the Justice Department advised the FISA Court that it will do this but not how it will be done); possible disclosure of FISA declarations under the Jencks Act if those field-agent declarants testify in criminal cases or other proceedings; and how to overcome the challenges of finding errors of omission rather than commission in FISA applications. (Although it is out of scope for this post, a broader review of permissible law enforcement investigative methods—including the use of deception—would also be possible.)

These difficult and wide-ranging issues will not be fully resolved fully by November 2020 or by January 2021. Apart from addressing the many and varied particular reforms now underway, a Biden administration will likely feel the need to foster continued cultural change at the FBI, including cooperation with the National Security Division and relations with the FISA Court. The FBI has richly earned some—but certainly not all—of the criticism it has endured over the past several years, and it will take a deft combination of carrots and sticks to make the necessary improvements in the months and years ahead. This reflects the fact that, despite its well-documented problems, the bureau remains a world-class law enforcement, security and intelligence agency staffed by a large number of dedicated and patriotic public servants.

The second big FISA issue is legislative. Three provisions of FISA have sunsets—allowing roving wiretaps, lone wolf surveillance targets and compelled production of tangible things. The Justice Department says the lack of these authorities is limiting investigations. Either Congress will enact new legislation to reauthorize these three provisions or it will not. If a new law is passed, it will come with many new requirements and issues that will need to be addressed—perhaps more new requirements than are in this House bill, which was supported by a bipartisan group that included Attorney General William Barr and the leadership of the House Judiciary Committee. The Senate recently passed an amended version of the House bill, expanding the new requirements, which the Justice Department has strongly opposed on the grounds that it “would unacceptably degrade our ability to conduct surveillance of terrorists, spies and other national security threats”—and as of this writing the House has not acted on the Senate amendments. On May 26, the President tweeted, “I hope all Republican House Members vote NO on FISA until such time as our Country is able to determine how and why the greatest political, criminal, and subversive scandal in USA history took place!” If new legislation is not enacted, the lack of FISA authority will have ongoing investigative impact—particularly concerning tangible things—and will create pressure to use other authorities more aggressively, including national security letters and grand jury subpoenas, which could create other problems. For example, national security letters have, in the past, produced their own inspector general reports documenting misuse.

FISA has generated significant controversy with a decidedly partisan aspect. But the operational elements of reform may admit of relatively more continuity, rather than change, as between the Trump administration and a Biden administration. Members of Congress from both major political parties have raised concerns about FISA; the statute and its implementation are technical and complex, requiring attention to detail for meaningful solutions; and inaccuracy of the sort demonstrated by the FBI is not desired by senior national security officials of either political party. The partisan political aspects of FISA will likely endure, but nuts-and-bolts efforts at accuracy reform and related implementation could well be similar even if Biden wins the election.

5. Foreign Investment and Technology

A Biden administration is likely to agree (at least implicitly) with the Trump administration’s assessment of the strategic national security challenge posed by China, including its Belt and Road Initiative and other foreign investment strategies. But it will also almost surely disagree with President Trump’s approach to meeting that challenge based on a belief that Trump has weakened the U.S. position in at least three ways: by unpredictably subordinating core national security issues to broader trade issues (for example, agricultural tariffs); by provoking disputes with adversaries and allies alike (for example, Canada); and by failing to emphasize U.S. participation in international standards-setting bodies for 5G and other emerging technologies. (As Michael Morell and I argued in 2018, “It’s not a trade war with China. It’s a tech war.”) A Biden administration may continue, however, to use law enforcement against Chinese technology theft and related activities.

As they develop their own approach, President Biden’s economic and national security teams will need to come to grips with at least three developments in the field of foreign investment. First, there are new statutory authorities expanding regulation of foreign investment in the United States (FIRRMA). Second, the Trump administration has made seemingly more aggressive use of Federal Communications Commission authorities to restrict licenses for telecommunications providers (for example, concerning China Mobile Telecom and perhaps four other Chinese companies). Third, there is Trump’s executive order designed to protect the U.S. bulk electric power system, issued on May 1, 2020, under the authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), and a prior order (later extended) concerning telecommunications. (For a discussion of these orders, see this interesting Lawfare post.) The recent order generally prohibits, but allows approval subject to a license, transactions in bulk-power equipment with foreign persons or entities. Although the bulk-power order is focused on hardware (and related installation services), it does not address software and other cybersecurity vectors, which Russia has used to attack Ukraine’s power grid. And, of course, it does not extend to the other 15 designated critical infrastructure sectors— including public health—or even to local power distribution networks, as to which supply-chain prohibitions on foreign sourcing might be much more difficult to impose at the federal level.

For its part, China recently published Cybersecurity Review Measures, effective June 1, covering network products and services in a wide range of critical sectors, and it is planning soon to release “China Standards 2035,” which will reflect the country’s interest in influencing and controlling technology standards. These and related measures from the Chinese government will deserve careful attention.

More broadly, if the United States does not lead in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence, the country probably will not be able to prevail, or even hold its own, against China and others—in the field of national security or elsewhere. An incoming Biden administration will need to review U.S. capabilities and the overall U.S. posture as compared to China and other competitors in many areas of technology.

6. International Agreements, Organizations and Relations

The Trump administration, it is fair to say, has been skeptical about international agreements and organizations, withdrawing or threatening to withdraw from many of them. In addition to the JCPOA (discussed above), there is also the Paris climate agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, UNESCO, the U.N. Human Rights Council, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, Open Skies and others. The president recently announced a suspension of funding for the World Health Organization. He has questioned the U.S. role in NATO (as he did during the 2016 campaign) and the NATO treaty, principally over the question of funding. Prominent Republican experts in international law have seen a larger pattern of a decline in the rules-based international order, as explained here.

A Biden administration is likely to be far more interested in participating in international agreements and organizations. It will need to assess which ones can be revived or rejoined—for example, the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris treaty will not become effective until at least early November 2020.

More generally, a Biden administration is likely to believe that the Trump administration’s approach to international relations has put the country on course to become a second-rate power, albeit with massive military capability, increasingly irrelevant (if not risible) on the worldwide stage. It is therefore likely to take very aggressive steps, both ceremonial and substantive, in an attempt to restore U.S. international standing and leadership.

7. Pandemics and Continuity of Operations and Government

Of course, a Biden administration will want to review the federal government’s ongoing response to the coronavirus and planning for possible future pandemics. Massive effort will be required to be ready for the next wave of the coronavirus or successor viruses. Among the authorities, policies and programs to be reviewed here would be those under the “big four” federal statutes allowing the president to respond to emergencies—the Stafford Act, the Public Health Service Act, the Defense Production Act and the Insurrection Act—as discussed here. Congressional calls to reorganize the government, some of which may be thoughtful and helpful, will abound and require response. Stockpiles will have to be replenished and relationships with state and local governments restored and strengthened. Social distancing and related guidelines will need to be adjusted. Messaging will need to be clear and accurate.

So far, the effects of the coronavirus on the intelligence community have been less visible—putting aside for now the more visible effects on the U.S. military, perhaps most notably on the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt. But I expect that there has been a significant, perhaps even severe, loss of momentum in some national security operations as a result of the virus. Classified work generally cannot be done from home, which magnifies the disruptive effect on the intelligence community and classified contractors. Bringing operations back online, and supporting them properly, may be challenging. A Biden administration will also want to review and revise continuity of operations and continuity of government (COOP and COG) plans along with pandemic planning and consider technological solutions to allow dispersed work in classified environments (see this recent article on the future of working from home in the intelligence community).

8. Apolitical Intelligence and Rule of Law

If Biden wins the election, his transition team and early leaders of national security elements will confront an executive branch under stress. Addressing that stress constructively will require understanding and deft management—qualities that are often in short supply in the early days of a new presidency. In particular, members of incoming Biden transition teams at the national security departments and agencies will need to trust their career (and some political) hosts more than feels natural, assist career staff in revitalizing the noble ideal of apolitical intelligence under law, and demonstrate their own commitment to that ideal.

The single biggest mistake that presidential transition teams routinely make is to mistrust the career officials who prospered during the prior administration. Explicitly or implicitly, this mistrust often rests on the assumption that those officials must have indulged partisan tendencies, or perhaps even compromised their ethics, to survive or thrive. That mistake will be especially hard to avoid this time, because the Trump administration has been so unusual. Skepticism may be more warranted than normal, but I think it will be less warranted than feels natural to some members of a Biden transition team and new political leadership. It is important to be on guard against excessive suspicion of the career staff, because they remain a valuable resource (which is not to say that they are always right).

For what it’s worth, having worked on transition from both directions—receiving the George W. Bush team and serving on Barack Obama’s incoming team—I believe that political appointees also can be helpful. For example, I would advise a Biden transition team to seek out the views of my successor, the current assistant attorney general for national security at the Justice Department, John Demers: We may disagree on many legal and policy matters, but I believe he would be honest and valuable in transition and I think well of him. The same is true of my long-term friend Courtney Elwood, the general counsel of the CIA. There are certain other political appointees whose views I would want to hear in transition, even if I would also question or disagree with them on the issues, concerning particular decisions or actions they may have made or taken while in office, and even as to their choice to remain in the Trump administration at all. It may feel awkward to a Biden transition team, but I think it is worth engaging with some Trump political appointees.

At the same time, a Biden administration will also need to understand, and be sensitive to, the special pressure that career staff have endured during the Trump administration. This is more than the usual tension that results from career officials carrying out policies, set by elected or appointed officials, that they personally do not support. On the contrary, executing policies set by political leaders is a vital pillar of the career intelligence and law enforcement workforce at its best. The problem is that in the Trump administration, this pillar has come into unprecedented conflict with a second and equally important obligation: the requirement to carry out the government’s policies within the framework set by law. Based solely on the publicly available evidence, I believe that this conflict has led to cognitive dissonance and perhaps trauma that may quickly come into focus if Biden wins the election and his transition teams arrive at the departments and agencies.

For those without experience in the field, it may be worth explaining further. Career national security officials rightly feel an obligation to follow the policies set by elected and appointed political leaders—for example, a direction to focus more on pursuing immigration violations than white-collar crimes, or to focus intelligence collection more on Iran than on Russia. This deference to political leaders is a critical element of intelligence and law enforcement culture. It resembles the U.S. military’s commitment to operating under civilian control.

But career officials also feel an obligation to carry out the policies made by elected officials within the limits of the law. A presidential demand to focus on immigration, for example, cannot (or at least should not) be carried out by mass detention without due process of all persons from certain ethnic or religious groups, or by falsifying evidence of misconduct by individual immigrants, or by treating them improperly. Similarly, a CIA intelligence focus on Iran cannot (should not) be carried out by covert action designed to influence U.S. public opinion in favor of military strikes, or by collecting kompromat on members of Congress from the opposition political party.

For many law enforcement and intelligence officials, the requirements to both follow policy and remain within the bounds of the law form a vital part of their ethos, their long-term survival strategy, and their psychic income. In the Trump administration, however, it appears that many officials have experienced an increasingly unmanageable conflict between them. Where policies set by elected officials are increasingly perceived to be unlawful, or even affirmatively designed to undermine rule of law, it is harder to square the circle of the two imperatives. The result has been cognitive dissonance and adaptive coping mechanisms—such as ignoring or minimizing presidential tweets and statements as “unofficial” and hence irrelevant—as well as a strict, heads-down focus on specific tasks. If career officials look up to witness the arrival of a new administration, however, they may also find themselves coming to grips with the experience of the preceding four years, with potentially strong reactions. A Biden transition team and new political leadership needs to be ready for this possibility and help the career staff regain balance and renew commitment to the vital paradigm of intelligence under law. With that in mind, they will want to review the legal advice dispensed by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel and other elements of the government during the preceding four years.

Finally, a Biden administration’s own commitment to the paradigm of apolitical intelligence under law will be tested early by at least three matters.

First, it seems likely that U.S. Attorney John Durham’s investigation of the intelligence community and the Russia investigation (and related matters) will be completed, and publicized, before November. But the fallout may endure for longer. Regardless, there will also be demands for a Biden administration to investigate the Trump administration, perhaps including Durham himself (and Barr, his boss)—that is, an investigation of the investigation of the investigation (see this letter from several senators for an example). A Biden administration will need to determine both how to respond to these demands and how (if at all) to talk about them publicly. This will likely require strong leadership from the new attorney general and strict discipline from the White House team, assuming that President Biden would not want to emulate his predecessor and comment publicly on potential criminal investigations and whether to “lock him up.” (Biden has said on television that he would not do that as president). New leaders of the relevant departments and agencies in the executive branch may consider their own careers and resist investigating their Trump administration predecessors in part because it will make them targets for political retaliation. Perhaps a congressional investigation or some other mechanism will take some of the pressure off the executive branch.

Second, the Trump administration, like every administration since Watergate, has had a written policy limiting contacts and influence between the White House and the Justice Department. But the president’s constant public comments have rendered the policy mostly a formalism. This is not a question of Article II power, but one of choosing to exercise power in a way that is designed to instill confidence in the justice system. Nor are concerns limited to direct communications between the White House and Justice Department—it is equally bad, if not worse, for the president to make his preferences known via Twitter or on television. With the experience of President Trump in the past, a new contacts policy will need to address those new modes of indirect communication, including by the president himself.

And third, congressional oversight of intelligence has suffered. The Senate Intelligence Committee has functioned reasonably well in some ways, although that could change in light of Chairman Richard Burr’s decision to step down. But the House Intelligence Committee has been problematic. This was true under former Chairman Devin Nunes, but it is not clear that things have improved much under the new chairman, Adam Schiff. For a thoughtful assessment of the committee’s difficulties under Nunes, and the possibility of improvement under Schiff, readers may want to listen to this podcast with former Sen. Saxby Chambliss, an alumnus of both the House and Senate Intelligence Committees. The beginning of a new presidential administration is an opportunity to reset congressional oversight of intelligence. It may not work, but it has to be tried.

Conclusion

As the country approaches the November 2020 elections, and the end of four of the most extraordinary years in American history, it is a good time to take stock of U.S. national security. If Trump wins reelection, the U.S. is likely to see more of the same. If, on the other hand, Biden wins, there will likely be a reversion to more traditional approaches, albeit launched from an extraordinary baseline. I have tried here to look ahead and consider more precisely what that might mean in the field of U.S. national security.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)