What Merrick Garland Said About Jan. 6

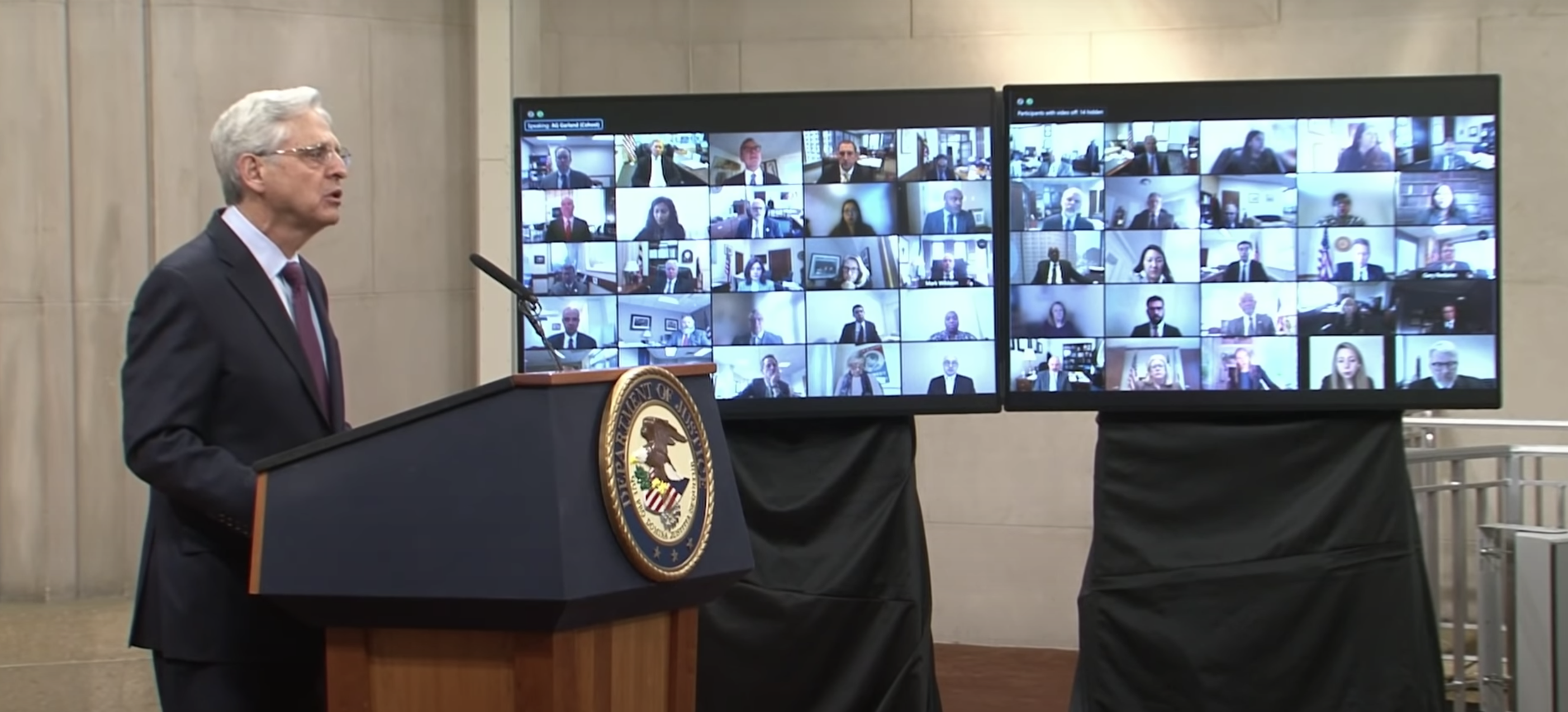

On the eve of the first anniversary of the Jan. 6 insurrection, Attorney General Merrick Garland delivered a speech reviewing the Justice Department’s efforts to investigate and prosecute those responsible for the attack on the Capitol.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Yesterday, on the eve of the first anniversary of the Jan. 6 insurrection, Attorney General Merrick Garland delivered a speech reviewing the Justice Department’s efforts to investigate and prosecute those responsible for the attack on the Capitol. “The Justice Department remains committed to holding all January 6th perpetrators, at any level, accountable under law,” he insisted, “whether they were present that day or were otherwise criminally responsible for the assault on our democracy.”

Garland’s remarks were notable both for what he said, and for the fact that he spoke at all. The attorney general has been remarkably quiet over the course of his tenure so far. In fact, the three of us argued just a few weeks ago that the attorney general needed to find his voice—that he should understand speaking publicly as a key part of his work in reestablishing the Justice Department’s independence and moral authority.

We suggested that Garland should speak up about the norms of independent, apolitical decisionmaking at the Department of Justice and how Garland was going about restoring those norms after the Trump presidency; what kinds of policies or factors were governing prosecutorial decisions about Jan. 6 cases; how the Department of Justice was thinking about the complex separation-of-powers questions raised by the referrals from Congress for criminal prosecution of witnesses defying subpoenas from the Jan. 6 committee; and how the Department was addressing the question of whether to revisit Attorney General Bill Barr’s conclusion that the Mueller Report had identified no crimes which should be prosecuted.

In his speech yesterday, Garland addressed some of these matters, left others unaddressed, and brought in a few major themes of his own—themes that sketched out a democracy protection agenda linking issues of political violence, politically-motivated threats against public officials and private actors and voting rights issues. The following are initial thoughts on Garland’s speech, what he covered, and what he omitted.

After a moment of silence to honor the five members of law enforcement who died directly or indirectly as a result of the Jan. 6 attack, Garland opened his address by talking about the investigation and prosecutions arising from those events.

He didn’t make much news here, no doubt on purpose. But he both defended the investigation and stressed its importance and magnitude. There is “no higher priority” for the Department right now than the Jan. 6 criminal matters, he said. He described the investigation as "one of the largest, most complex, and most resource-intensive investigations in our history." The department has issued more than five thousand subpoenas and search warrants; seized approximately two thousand devices; reviewed tens of thousands of hours of video footage and 15 terabytes of data, and received more than 300,000 tips from the public. More than 725 defendants have been arrested and charged to date, he said.

Seemingly in response to criticism that mostly smaller fry defendants have been charged to date while those behind the planning of the insurrection have not, Garland described the department’s approach as consistent with “well-worn prosecutorial practices.” Large investigations, he explained, start with the more junior people and the more easily proved cases. The public at first sees short sentences (or no jail time at all) handed out, and an absence of the more notorious figures being charged. Garland strongly implied that more significant actions are coming down the pike. Junior people flip on more senior people. And perpetrators who were not directly involved in violence but played planning or other behind-the-scenes roles must be reached with more time-consuming and complex investigations. The attorney general seemed to all but promise that more serious charges against those centrally responsible for the riot are coming: “The actions we have taken thus far will not be our last.”

It’s hard to say exactly what to make of this statement. It could imply trouble for political leadership that engaged and encouraged the rioters, or the operatives who organized the event itself. Or it could, in the alternative, mean that the Justice Department is continuing aggressive investigations of groups like the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, some of whose members have already faced conspiracy charges in relation to the riot. In the case of both of these groups, a number of key leaders who were not physically involved in the violence themselves remain unindicted, despite evidence that they were in contact with those who were. Or perhaps the department might also be considering unveiling charges of seditious conspiracy or “rebellion or insurrection,” statutes weighted with political significance that the Justice Department has not yet made use of when it comes to Jan. 6.

The ambiguity about future prosecutions was characteristic of Garland’s speech. The attorney general focused less on giving specifics about how the Jan. 6 investigation is progressing and more on explaining the principles guiding the Justice Department’s thinking, including his own thinking on why he doesn’t want to say more. The department “will and . . . must speak through our work,” Garland explained. “Anything else jeopardizes the viability of our investigations and the civil liberties of our citizens.” Should the department behave differently and say more given the extraordinary nature of the current situation? Not according to Garland: “We conduct every investigation guided by the same norms. And we adhere to those norms even when, and especially when, the circumstances we face are not normal.”

Articulating the values that guide him is valuable. We argued previously that Garland needed to speak publicly about his vision for the department precisely because so many Americans are unfamiliar with the norms governing its work. Here, he is doing just that.

But it is also frustrating to someone looking for any kind of guidance about where this is all heading. It would be a gross overreading of what Garland said–and didn’t say–to think that the public learned anything yesterday about whether the Justice Department is criminally investigating anyone in political leadership for a supposed role in encouraging the insurrection, much less whether such people might face charges. This point includes, but is not limited to, former President Donald Trump. On all such matters, Garland remained silent.

But Garland seemed to have a larger agenda for his speech—one that connected prosecuting the Jan. 6 insurrectionists to countering other anti-democratic tendencies in the country. He bemoaned a tide of political and ideological threats of violence in the United States, a tide that extends much further than the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol: “the rising violence and criminal threats of violence against election workers, against flight crews, against school personnel, against journalists, against members of Congress, and against federal agents, prosecutors, and judges.” On this issue, the attorney general cited his personal experience. Invoking the Oklahoma City bombing case, which he supervised while at the Justice Department in the 1990s, Garland averred that “The time to address threats is when they are made, not after the tragedy has struck.” He pledged a vigorous federal response to “the rise in violence and unlawful threats of violence in our shared public spaces and directed at those who serve the public.”

Garland also linked these threats to issues of civil rights and voting rights. Expressly referencing violence against would-be voters, particularly Black Americans, during post-Civil War Reconstruction in the South and the Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, he spoke at length about the department’s historic role in protecting access to the franchise. He criticized the Supreme Court for restricting the reach of the Voting Rights Act, and criticized state legislatures which, in his view, have been “mak[ing] it harder for millions of eligible voters to vote and to elect representatives of their own choosing,” ranging from “practices and procedures that make voting more difficult; to redistricting maps drawn to disadvantage both minorities and citizens of opposing political parties; to abnormal post-election audits that put the integrity of the voting process at risk; to changes in voting administration meant to diminish the authority of locally elected or nonpartisan election administrators.” He blamed these measures in part on unfounded claims–most vocally made by Trump, though Garland never named him or even referred to him directly–that there was widespread fraud in the 2020 election.

In short, Garland clearly drew a connection between the efforts to violently overturn the 2020 election, the growing use of threats and violence to try to keep public officials from doing their jobs, restrictions on voting access, and false narratives about voting fraud. Jan. 6 pulled together these trends: the insurrectionists sought to threaten Congress into effectively erasing the votes of Americans who did not support their desired candidate. Though Garland cautioned that “[t]hese acts and threats of violence are not associated with any one set of partisan or ideological views,” quite clearly he is describing a growing lawlessness and attacks on democracy that are predominantly coming from the political right, and often people associated with the Republican Party.

In this way, the attorney general used the anniversary of Jan. 6 as an opportunity to consider the Justice Department’s role in protecting democratic governance more broadly. “The obligation to keep Americans and American democracy safe is part of the historical inheritance of this department,” he argued.

But it was also notable what Garland chose not to include in his overview of “keeping American democracy safe”—in particular, how the department understands Trump’s abuses of power separate from Jan. 6. As we hoped he might, Garland did speak about the norms that should guide the Department of Justice, explaining that,

Over 40 years ago in the wake of the Watergate scandal, the Justice Department concluded that the best way to ensure the department’s independence, integrity, and fair application of our laws—and, therefore, the best way to ensure the health of our democracy—is to have a set of norms to govern our work.

The central norm is that, in our criminal investigations, there cannot be different rules depending on one’s political party or affiliation. There cannot be different rules for friends and foes. And there cannot be different rules for the powerful and the powerless.

There is only one rule: we follow the facts and enforce the law in a way that respects the Constitution and protects civil liberties.

While this is fine as far as it goes, it is somewhat narrow. The norms established to guide the department after Watergate were more robust and far-reaching than Garland allows here. One crucial norm has been that, absent unusual circumstances, the White House is not involved in decisionmaking about specific investigations or prosecutions—a policy about which Garland certainly knows, since he helped implement it as a young aide to the attorney general in the 1970s and recently implemented his own version of the policy. The White House sets policy to guide the Justice Department, and occasionally presidents must weigh in on matters of unusual sensitivity. For example, President Obama’s decision in 2010 to do a spy-swap with Russia rather than allow the Justice Department to move forward with the incarceration of Russian sleeper agents. But otherwise the White House butts out. This norm was flagrantly abused by Trump and members of his administration. But Garland said nothing about it.

Garland also said nothing about other kinds of “Trump-proofing” of the executive branch—nothing, for example, about legislation that has passed the House of Representatives that would address many abuses of the Trump era. HR 5314, the Protecting Our Democracy Act, touches on many issues concerning the Justice Department. Among other things, it would ban presidential self-pardons; require the department to submit information to Congress about pardons of the president’s family, administration team, or campaign staff; amend the criminal code to clarify that bribery in connection with a pardon is prohibited; suspend the statute of limitations for federal offenses committed by a sitting president or vice president; protect inspectors general from baseless or bad faith removal by the president; and require record-keeping about contacts between the White House and the Justice Department. Garland was silent on these questions.

Garland’s department clearly has views about many or all of these matters, a significant cohort of which implicate the department’s equities. It may well think that some of the bill’s provisions are unwise or contrary to the department’s views of the constitutional separation of powers. For that reason, it would be useful to know how the attorney general is thinking about such questions. But more fundamentally, it would be useful to know whether such post-Trump reform proposals play any role in his vision of democracy protection as a central priority for his department. In other words, is Garland’s tripartite vision of the department’s democracy-protective function as articulated in this speech—consisting of prosecuting Jan. 6 perpetrators, going after those who threaten or commit political violence more generally, and protecting voting rights and election integrity—the sum total of his vision of the function? Or is there a reform element he just didn’t address in the speech?

Garland also declined to speak about the possibility of any accountability for the many Trump-era misdeeds that took place before Jan. 6. To pick only one example we raised in our earlier piece, the Mueller Report famously found facts that might have constituted obstruction of justice by the former president, but Special Counsel Robert Mueller declined to opine on whether the law had actually been broken, out of deference to department policy banning the indictment of a sitting president. Now out of office, Trump no longer has that immunity.

Even as the statute of limitations on the potential obstruction offenses will soon begin to expire, Garland offered no insight into whether his department has decided to affirm or revisit former Attorney General Barr’s decision that prosecution of Trump for facts found by Mueller was unwarrantedWhy these omissions? One possibility is that Garland feels the matter of accountability for Jan. 6 eclipses other Trump-era offenses in importance, especially when framed as a question of protecting democracy itself. Another possibility is that the omission indicates that the Justice Department has closed the book on the Mueller Report and does not intend to return to the question of Trump’s possible obstruction of justice—effectively letting Barr’s judgment stand. Another is that the attorney general understands these issues as distinct from Jan. 6 and simply intends to address them another time; this was, after all, a speech on the anniversary of the Jan. 6 uprising, not a speech on the anniversary of the Mueller Report.

In the end, this speech addressed some issues usefully, detailed a coherent and attractive vision of the department’s attitude towards democracy protection—and left a lot of questions unanswered. Some of these questions probably cannot responsibly be answered. But others can and should. It is probably unreasonable to expect Garland to answer all such questions in a single speech, so the merits of this speech probably need to be assessed in the context of whatever future speeches he gives. If it proves to be the speech that broke the attorney general’s silence and becomes the first in a series, it will be remembered for what Garland began saying in it. If, on the other hand, it stands on its own, it will be more notable for the spaces between the attorney general’s words.