What’s Going On in Footnote 3?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In retrospect, the most consequential part of the oral argument in Trump v. United States—or “the presidential immunity case”—took place early in what became a marathon hearing. Chief Justice John Roberts posed what seemed like a skeptical hypothetical to Donald Trump’s lawyer, a man named D. John Sauer.

“Well, what if you have—let’s say the official act is appointing ambassadors, and the president appoints a particular individual to a country, but it’s in exchange for a bribe. Somebody says, I’ll give you a million dollars if I’m made the ambassador to whatever. How do you analyze that?”

Sauer argued in response that bribery is not an official act, so there would be no immunity in that case, but the chief justice wasn’t quite ready to let go of his question. “Accepting a bribe isn’t an official act,” he agreed, “but appointing an ambassador is certainly within the official responsibilities of the president. So how ... does your official acts ... boundary come into play?”

Analogizing the question to cases under the Speech or Debate Clause, which immunizes legislators for official legislative acts, Sauer responded that “the indictment has to be expunged of all the immune official acts, so there has to be a determination what’s official [and] what’s not official.”

Roberts, quite understandably, found this unsatisfying: “Well, you expunge the official. You say, okay, we’re prosecuting you because you accepted a million dollars. They’re supposed to ... not say what it’s for because the what-it’s-for part is within the president’s official duties?”

Sauer, like a good appellate advocate, skated over Roberts’s question, saying that “[t]here has to be, we would say, an independent source of evidence for that.” And then he whisked the conversation onto safer ground, talking about how the Jan. 6 indictment strikes at the “heartland of presidential power.”

The issue of whether official acts immunity would prevent prosecution of a former president for bribery by preventing inquiry into the official act he committed in exchange for the thing of value comes up several more times at oral argument. And it comes up in the court’s opinion too—although this time with a bit of a role reversal. In the opinion, it’s Justice Amy Coney Barrett who objects that the court’s ruling would preclude a bribery prosecution, and it’s Chief Justice Roberts—having adopted the role of Sauer—who cryptically suggests that prosecutors might use some extrinsic piece of evidence of an official presidential act and then hastily moves on to another subject.

The matter is important in both doctrinal and practical terms. In doctrinal terms, the exchange between Barrett and Roberts reveals one of the weakest aspects of the majority’s opinion—one that Roberts appears to understand, given that he probed Sauer on exactly the same point at oral argument. In practical terms, the matter is important because it might—and we must stress might—open up a loophole in the Court’s opinion that Special Counsel Jack Smith could exploit on remand to one degree or another.

The Elusive Footnote 3

To unpack this, let’s start with the opinion itself, in which Chief Justice Roberts writes for himself and four other members of the Court that not only is the president presumptively immune from prosecution for official acts, but that evidence of those official acts cannot be used to prosecute him for unofficial acts. The government had argued that a jury should be allowed to “consider” evidence concerning the president’s official acts and that such evidence would “be admissible to prove, for example, [Trump’s] knowledge or notice of the falsity of his election-fraud claims.” But Roberts and the majority reject this:

That proposal threatens to eviscerate the immunity we have recognized. It would permit a prosecutor to do indirectly what he cannot do directly—invite the jury to examine acts for which a President is immune from prosecution to nonetheless prove his liability on any charge.

Justice Barrett, who joins the majority for the bulk of its opinion, does not join this portion of the decision. “The Constitution does not require blinding juries to the circumstances surrounding conduct for which Presidents can be held liable,” she writes. And she, as her example, turns to the very hypothetical with which Roberts himself confronted Sauer at oral argument a few weeks earlier.

“Consider a bribery prosecution—a charge not at issue here but one that provides a useful example,” she writes.

“The Constitution, of course, does not authorize a President to seek or accept bribes, so the Government may prosecute him if he does so. ... Yet excluding from trial any mention of the official act connected to the bribe would hamstring the prosecution. To make sense of charges alleging a quid pro quo, the jury must be allowed to hear about both the quid and the quo, even if the quo, standing alone, could not be a basis for the President’s criminal liability.”

The chief justice responds in a single footnote, footnote 3. His response is remarkably similar to that of Sauer at the oral argument. Footnote 3 reads:

JUSTICE BARRETT disagrees, arguing that in a bribery prosecution, for instance, excluding “any mention” of the official act associated with the bribe “would hamstring the prosecution.” ... But of course the prosecutor may point to the public record to show the fact that the President performed the official act. And the prosecutor may admit evidence of what the President allegedly demanded, received, accepted, or agreed to receive or accept in return for being influenced in the performance of the act. ... What the prosecutor may not do, however, is admit testimony or private records of the President or his advisers probing the official act itself. Allowing that sort of evidence would invite the jury to inspect the President’s motivations for his official actions and to second-guess their propriety. As we have explained, such inspection would be “highly intrusive” and would “ ‘seriously cripple’ ” the President’s exercise of his official duties. ... And such second-guessing would “threaten the independence or effectiveness of the Executive.

There’s a lot happening in this footnote, and the more one reads it the more inscrutable it becomes. It’s worth unpacking its inscrutability systematically.

The first thing to note here is a doctrinal point: Roberts plays fast and loose with the idea of immunity—at least as the term is used in related contexts—in the footnote’s second sentence. Normally, when we say someone is “immune” for a given act, we mean he or she cannot be prosecuted for it at all. As Roberts himself puts it, “The essence of immunity ‘is its possessor’s entitlement not to have to answer for his conduct,’ in court.”

When we say a senator is protected by Speech or Debate Clause immunity, we thus do not mean that prosecutors can “point to the public record to show the fact that [she] performed the official [legislative] act.” We do not mean merely that the prosecutor has to point to the congressional record of her giving a particular speech, for which she took a bribe. And we do not mean only, as Roberts writes of the president, that “[w]hat the prosecutor may not do ... is admit testimony or private records of the [senator] or [her] advisers probing” her Senate floor speech.

We mean, rather, that the senator cannot be prosecuted for the activity in question, whether that behavior is reflected in testimony or in public record evidence. It is difficult to square the sentence “The essence of immunity ‘is its possessor’s entitlement not to have to answer for his conduct’ in court” with the sentence in footnote 3: “But of course the prosecutor may point to the public record to show the fact that the President performed the official act.”

We mean the same with respect to other immunities. A foreign diplomat does not merely have a privilege against being forced to testify or having his aides testify about his private performance of his duties. He is not amenable to criminal prosecution at all without a waiver of his immunity by his government. Prosecutorial and judicial immunities are no different.

The Speech or Debate Clause cases are explicit on this point. Indeed, this precise issue showed up in the seminal 1966 case of U.S. v. Johnson, in which a member of Congress was prosecuted for—among other things—one of the very crimes of which Trump now stands accused: conspiracy to defraud the United States under 18 U.S.C. § 371. And the district court case then, just as Barrett and the government argue should be the case here, involved evidence of protected acts, indicted as part of a supposedly unprotected conspiracy.

The Supreme Court then, like Roberts today, was having none of it:

The language of the Speech or Debate Clause clearly proscribes at least some of the evidence taken during trial. Extensive questioning went on concerning how much of the speech was written by Johnson himself, how much by his administrative assistant, and how much by outsiders representing the loan company. The government attorney asked Johnson specifically about certain sentences in the speech, the reasons for their inclusion and his personal knowledge of the factual material supporting those statements. In closing argument, the theory of the prosecution was very clearly dependent upon the wording of the speech. In addition to questioning the manner of preparation and the precise ingredients of the speech, the Government inquired into the motives for giving it.

The constitutional infirmity infecting this prosecution is not merely a matter of the introduction of inadmissible evidence. The attention given to the speech’s substance and motivation was not an incidental part of the Government’s case, which might have been avoided by omitting certain lines of questioning or excluding certain evidence. The conspiracy theory depended upon a showing that the speech was made solely or primarily to serve private interests, and that Johnson, in making it, was not acting in good faith, that is, that he did not prepare or deliver the speech in the way an ordinary Congressman prepares or delivers an ordinary speech.

But unlike Roberts, the court did not remotely entertain the notion that the public record of the speech could be admissible as evidence of the conspiracy. Indeed, the court remanded the matter so that, “With all references to this aspect of the conspiracy eliminated, we think the Government should not be precluded from a new trial on this count, thus wholly purged of elements offensive to the Speech or Debate Clause” (emphasis added). Note here that the remedy the court ordered did not entertain either merely purging the case of references to “testimony or private records of the President or his advisers probing the official act itself.” It required that “all references to this aspect of the conspiracy [be] eliminated” entirely.

Roberts’s opinion, as Sauer did at argument, elides this point—which both men surely understand is a departure from the Supreme Court’s immunity doctrine in other contexts.

The court’s opinion in the immunity case describes itself, and has generally been described, as setting up three categories of presidential acts: (1) acts reflecting core and exclusive presidential powers, where immunity is absolute, (2) other official acts, where immunity is presumptive but may (or may not) be overcomable with a prosecutorial showing that legitimate presidential authority would not be threatened by prosecution, and (3) personal conduct, where immunity does not exist.

But Roberts’s footnote 3, whatever the motivation behind it, sets up a nebulous and ill-defined exception to the evidentiary rule. The exception includes official acts that are immune in the sense that they may not be charged as crimes, but it maintains that are not fully immune, insofar as the public record of them—though not testimony or evidence about the president’s communications and thinking surrounding them—may be introduced as evidence of some other unprotected charged crime.

This exception might be quite narrow or quite broad, depending on how the lower courts—and ultimately the Supreme Court—interpret the matter.

Notably, the opinion itself gives essentially no guidance on the question of the scope or parameters of this loophole save the above-quoted words from Roberts’s footnote. To reiterate, that guidance is the following: “the prosecutor may point to the public record to show the fact that the President performed the official act. And the prosecutor may admit evidence of what the President allegedly demanded, received, accepted, or agreed to receive or accept in return for being influenced in the performance of the act.” But “the prosecutor may not ... admit testimony or private records of the President or his advisers probing the official act itself.”

Before trying to figure out how this guidance might apply in the Jan. 6 case, consider a few important threshold points:

First, the opinion does not specify what it means by “public record” evidence of an official act. Note that the plain text of the footnote refers not to the official record of the act, which might be limited to the Federal Register entry recording the action or some such. It seems to refer, rather, to something broader. But what does it include and what does it exclude? It presumably doesn’t include press coverage of the act, which would be hearsay anyway. But as we shall explain, there is a lot of gray area between press coverage and the official record. And there is a lot of gray area too between “the public record” and “testimony or private records of the President or his advisers.” There is thus a great deal of variance in the possible answers to this question. A huge amount of the future vitality of the Jan. 6 case may depend on how the lower courts—and ultimately the Supreme Court—interpret this phrase.

Second, it’s not clear whether the “public record” evidence described by the majority in footnote 3 might be uniquely admissible in bribery prosecutions or whether, conversely, bribery is merely an example of a crime of which official presidential acts may be evidence. Perhaps Roberts’s point about bribery is generalizable to other such offenses.

The reason for the opacity on this point is that the crime of bribery presents something of a special problem for the majority’s immunity analysis. Bribery is, after all, explicitly included in the Constitution as a ground for the impeachment and removal of the president. And as Justice Sonia Sotomayor notes in her dissent, the Impeachment Judgement Clause “presumes the availability of criminal process” by establishing that an official impeached and convicted by the Senate “shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgement and Punishment, according to Law.” The clause thus implies that a former president may, at a minimum, be prosecuted for the same conduct that resulted or could have resulted in his or her impeachment—including the crime of bribery.

The majority, for its part, responds to this argument by claiming that the clause “does not indicate whether a former president may, consistent with the separation of powers, be prosecuted for official conduct in particular.”

But that’s precisely why bribery presents a unique problem for the majority: The crime of bribery implicates official acts “almost by definition,” as Sotomayor puts it. The Supreme Court has held that the crime of bribery codified in 18 U.S.C. § 201(b) requires a quid pro quo—a “specific intent to receive something of value in exchange for an official act.”

So it’s conceivable that Roberts’s footnote is really an attempt to address the bribery problem specifically, not a general statement that public evidence of official acts is fair game.

But again, the text of the footnote seems to sweep more broadly than just bribery. Roberts’s use of the phrase “for instance” in the footnote, suggests that he is using the bribery statute as an example of a broader class of offenses. Barrett likewise uses bribery as an example. But is Roberts then conceding that any public record, however defined, of any official act is admissible?

Third, there’s some ambiguity as to whether the “public record” evidentiary exception includes both presumptively immune official conduct in category 2 and absolutely immune conduct from category 1. In the footnote, Roberts merely writes that in a bribery prosecution “the prosecutor may point to the public record to show that the President performed the official act.” He doesn’t distinguish between core and non-core official acts.

There are good reasons to think that the public record exception includes not merely some activity within the category of presumptively immune conduct but also activity within the absolutely immune conduct too. For one thing, neither Barrett nor Roberts seem to distinguish between “presumptively” or “absolutely” protected conduct in this discussion. What’s more, Roberts notably does not suggest that taking bribes in exchange for a pardon would be different from taking bribes in exchange for some official act that garners lesser protection.

But it’s also possible that the admissibility of “public record” evidence described in footnote 3 includes only presumptively immune conduct. In the footnote, after noting that public record evidence that a president performed an official act would be admissible in a bribery prosecution, Roberts goes on to engage in the sort of analysis the court performs when determining whether prosecutors can overcome a presumptive immunity with respect to a particular act. Specifically, he distinguishes the admissibility of “public record” evidence from “private records of the President or his advisers” on grounds that admission of the latter would be “highly intrusive” and would “seriously cripple” the president's exercise of his official duties. So perhaps footnote 3 is merely an example of the court engaging in some variation of the type of analysis it performs when determining whether presumptively immune conduct presents a “danger of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.”

With these considerations in mind, let’s try to translate footnote 3 into something useful not in the hypothetical debate between the chief justice and Justice Barrett but in the actual case before them both.

The case against Trump is not a bribery case, so the language in Roberts’s footnote has to be translated into the language of conspiracy to be useful. Assuming the answers to some of the questions above to be relatively lenient, one might, for this purpose, crudely reformulate the matter for this purpose as follows: “[T]he prosecutor may point to the public record to show the fact that the President performed the official act. And the prosecutor may admit evidence of what the President allegedly agreed to, demanded, received, ordered, conspired in or directed in connection with the performance of the act.” But “the prosecutor may not ... admit testimony or private records of the President or his advisers probing the official act itself.”

Footnote 3 and Mike Pence: A Case Study

Let’s try to apply this principle articulated in footnote 3 to a major issue in the indictment: Trump’s pressure campaign on Vice President Mike Pence. The court suggests that the pressure on Pence to reject the electoral vote count was official conduct, though it remands to the lower courts to determine whether the president’s presumptive immunity for that conduct might be overcome.

While these conversations are deemed to be official acts, they are also acts that gave rise to a significant set of public records.

So imagine for a moment that the lower court were to take the view—despite some reason to consider it otherwise—that the prosecution cannot overcome the presumption of immunity. That would leave the question of whether the public records of that pressure campaign are legitimate evidence admissible for some specific evidentiary purpose under footnote 3. The consequence of this would be that while Pence and his aides would not be able to testify about private White House matters concerning the pressure they faced, the public record evidence of those discussions might still be still available.

How much of it?

The simple answer is that we don’t know. Depending on how the court interprets footnote 3, maybe a little bit, maybe none, maybe quite a bit, maybe a great deal.

Consider the section of the indictment entitled “The Defendant’s Attempts to Enlist the Vice President to Fraudulently Alter the Election Results at the January 6 Certification Proceeding” in light of this question.

As the Jan. 6 congressional certification approached and Trump’s other efforts “to impair, obstruct and defeat the federal government function” failed—the indictment alleges—Trump sought to pressure Pence to use his ceremonial role at the proceeding to “fraudulently alter the election results.” The indictment describes two ways in which Trump attempted to do so. The first is that he relied on “knowingly false claims of election fraud” to convince Pence that he should accept the fraudulent electors, reject legitimate ones, or send electoral votes back to state legislatures for review. The evidence of Trump’s and Pence’s private conversations would now all be off limits, right?

Certainly, Pence could not be called to testify about his conversations with Trump under these circumstances. But Pence has written a book. And in that book, he described repeatedly and in some detail the pressure campaign Trump subjected him to—including a number of the specific conversations at issue in the indictment.

He describes, for example, the conversation on Jan. 2, 2021, in which Trump told Pence he was “too honest” and asked him “If [the Constitution] gives you the power, why would you oppose it?”

It describes a conversation the following day in which Trump insisted to Pence that “you have the absolute right to reject electoral votes” and told him that “You can be a historic figure ... but if you wimp out, you’re just another somebody.” And he describes a conversation on Jan. 5 in which Trump told Pence that “I think you have the power to decertify,” and told him it just “takes courage,” and threatened, “Well, I’m gonna have to say you did a great disservice.”

This incident shows up specifically in the indictment, which claims that Trump met with Pence—privately—and threatened him with public criticism if he refused to obstruct the certification.

Pence’s book is certainly a type of public record, but it’s not an official record. Assuming Pence is not able to testify about his conversations with Trump, might such material constitute a public record of official acts under footnote 3?

Material from Pence’s book is presumably inadmissible in any event as hearsay, but the hearsay rules are subject to a number of exceptions. So it’s conceivable that individual passages might meet the rules for one or more of these exceptions. For present purposes, in any event, the relevant question is whether they are barred by the court’s immunity ruling.

Then there are Trump’s own public statements about the meetings with Pence, both those issued at the time and those issued in retrospect. Are they public records of an official act?

For example, despite Pence’s refusal to consider the plan to obstruct the certification of electoral votes, the indictment alleges that Trump “approved and caused” his campaign to issue a “false” statement about the Jan. 2, 2021, meeting: “The Vice President and I are in total agreement that the Vice President has the power to act.”

Presumably the public statement here is admissible, even if Trump’s approval and direction of his campaign to do something is deemed to be an official act.

Trump made a great many public statements throughout this period, many of them in the form of tweets. In carrying out this campaign to enlist Pence in his effort to overturn the results of the election, Trump on Dec. 23, 2020, retweeted a “memorandum for the President” titled “Operation PENCE CARD,” which stated, among other things, that the vice president is authorized to “unilaterally disqualify legitimate electors.” The same day, the indictment says, “co-conspirator 2,” who has been identified as John Eastman, “circulated a two-page memorandum outlining a plan for the Vice President to unlawfully declare the Defendant the certified winner of the presidential election.”

Tweets and retweets present an easier question in our view than does a book by the former vice president. Tweets and other public statements are probably also official acts, but they are official acts that create public records—like a pardon issued in connection with a bribe. Indeed, in the case of a tweet, the official act is its own public record, and it’s an official act that may comment on a prior official act. Unlike much of Pence’s book, Trump’s tweets would likely not be considered inadmissible hearsay under the Federal Rules of Evidence.

The question of the status of tweets is important because the indictment alleges that when his private strategy of pressuring Pence failed, Trump then proceeded to use “a crowd of supporters that he had gathered in Washington, D.C.” to pressure the vice president “to fraudulently alter the election results.” A great deal of the evidence of this activity took place in the form of presidential tweets and statements. Assuming these statements are official acts, they all appear to be official acts for which the conduct itself constitutes its own public record. Does that make them admissible too?

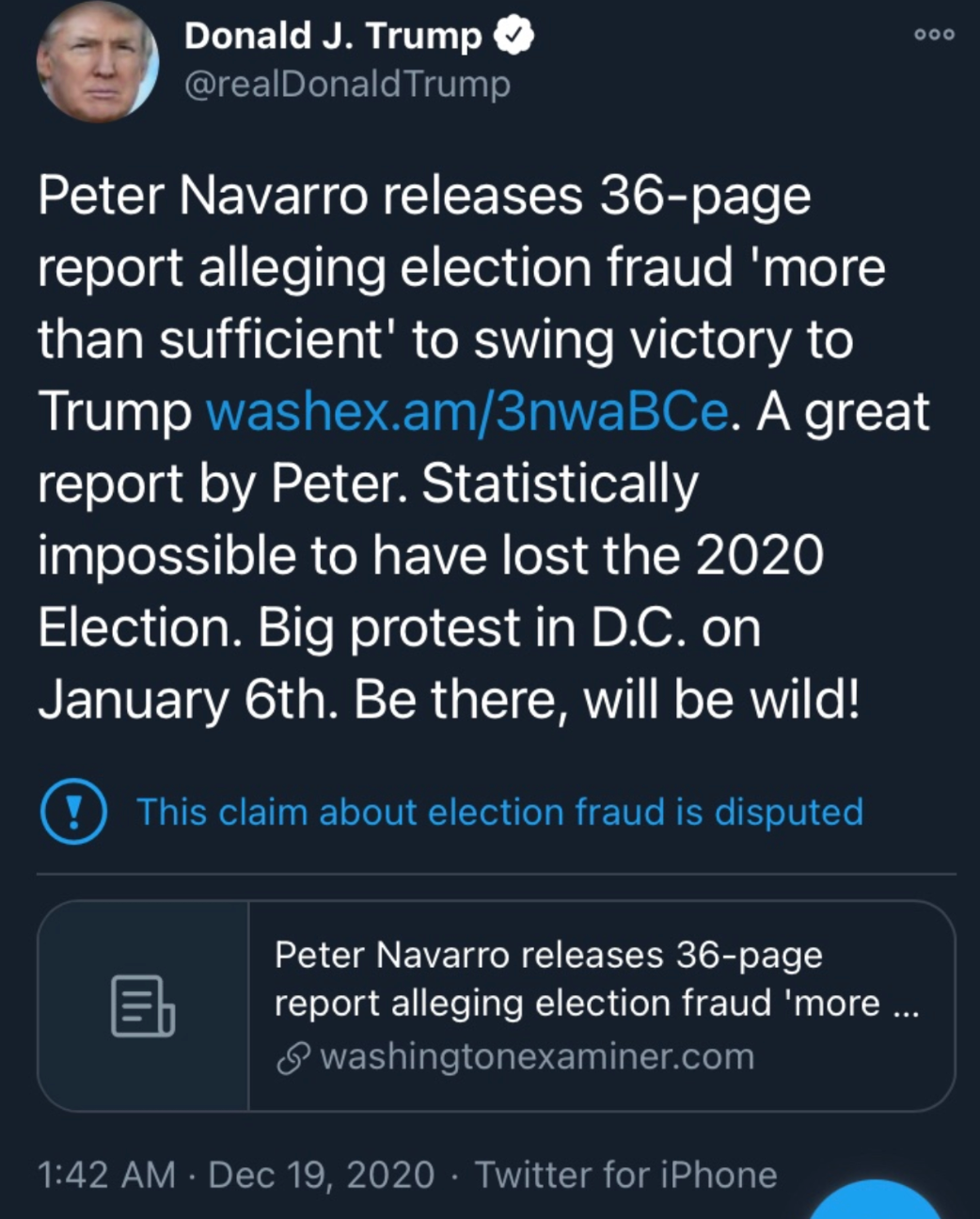

The indictment alleges that Trump began urging his supporters to travel to D.C. for the congressional certification on Dec. 19, 2020, with tweets that claimed people should “be there, will be wild!”

Trump continued to urge supporters to show up throughout late December, the indictment states. On Jan. 1, 2021, for example, Trump posted a tweet reminding his supporters to meet in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6. Trump sent this tweet, the indictment asserts, within hours of a phone conversation with Pence, in which the vice president told Trump that there was “no constitutional basis” for him to reject or return votes to the states during the joint session of Congress.

Again, testimony concerning that phone call is now presumably inadmissible, and, again, an account of the phone call shows up in Pence’s book—excerpts of which are potentially hearsay and thus possibly excludable on that basis. Pence writes that “I told him, as I had told him many times before, that I did not believe I possessed the power under the Constitution to decide which votes to accept or reject. He just kept coming.”

The prospects of a trial look very different if the tweet is admissible and if Pence is allowed to testify that he wrote this passage and that it accurately reflects his memory than if the tweet is not admissible and the passage is not either.

The indictment further alleges that, despite Pence’s rejection of the plan and the warnings about the consequences of contesting the election further, Trump continued to encourage his supporters to travel to D.C. on Jan. 6. At the same time, he continued posting public statements about the supposed authority that would allow the vice president to “reverse the election outcome.” And there are a lot of tweets that specifically support this claim:

- At 10:27 a.m. on the morning of Jan. 5, 2021, the indictment alleges that he tweeted, “See you in D.C.”

- At 11:06 a.m.—just 40 minutes after Trump’s “See you in D.C.” tweet—he wrote: “The Vice President has the power to reject fraudulently chosen electors.”

- According to the indictment, Trump posted again at 5:05 p.m.: “Washington is being inundated with people who don’t want to see an election victory stolen by emboldened Radical Left Democrats. Our Country has had enough, they won’t take it anymore! We hear you (and love you) from the Oval Office. MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!”

- Several minutes later, at 5:12 p.m., he wrote in a tweet not specifically mentioned in the indictment: “I hope the Democrats, and even more importantly, the weak and ineffective RINO section of the Republican Party, are looking at the thousands of people pouring into D.C. They won’t stand for a landslide election victory to be stolen.”

- At 5:43 p.m., the indictment notes that Trump tweeted: “I will be speaking at the SAVE AMERICA RALLY tomorrow on the Ellipse at 11 AM Eastern. Arrive early—doors open at 7AM Eastern. BIG CROWDS!”

Some of these tweets were specifically aimed at pressuring Pence. The indictment alleges that Trump, starting in the “early morning hours” on Jan. 6, made “knowingly false statements aimed at pressuring the Vice President to fraudulently alter the election outcome” and “raised publicly the false expectation” that Pence might do so. For example:

- At 1:00 a.m. on Jan. 6, Trump tweeted: “If Vice President @Mike_Pence comes through for us, we will win the Presidency. Many States want to decertify the mistake they made in certifying incorrect & even fraudulent numbers in a process NOT approved by their State Legislatures (which it must be). Mike can send it back!”

- Hours later, at 8:17 a.m., Trump posted the following: “States want to correct their votes, which they now know were based on irregularities and fraud, plus corrupt process never received legislative approval. All Mike Pence has to do is send them back to the States, AND WE WIN. Do it Mike, this is a time for extreme courage!”

Within an hour of the Trump call with Pence on the morning of Jan. 6, the charging document alleges that two co-conspirators, Rudy Giuliani and Eastman, falsely told a crowd gathered near the Capitol that the vice president could obstruct the certification proceeding. Giuliani told the crowd that “every single thing that has been outlined as the plan for today is perfectly legal.” He continued: “It is perfectly appropriate given the questionable constitutionality of the Election Counting Act of 1887 that the Vice President can cast it aside and he can do what a president called Jefferson did when he was Vice President. He can decide on the validity of these crooked ballots, or he can send it back to the legislators, give them five to 10 days to finally finish the work.” As the indictment notes, Giuliani also called for “trial by combat” during this speech.

Eastman, for his part, said: “[A]ll we are demanding of Vice President Pence is this afternoon at 1 o’clock he let the legislatures of the State look into this, so we get to the bottom of it and the American people know whether we have control of the direction of our Government or not. We no longer live in a self-governing republic if we can’t get the answer to this question.”

These speeches are certainly admissible, but they are much more powerful as evidence if the material from the Pence book is somehow admissible than if it is not.

This brings us to Trump’s own speech on the Ellipse, which may or may not constitute an official act but which, again—like Trump’s tweets—creates its own public record. The indictment alleges that Trump “made multiple knowingly false statements integral to his criminal plans to defeat the federal government function, obstruct the certification, and interfere with others’ right to vote and have their votes counted.” Prosecutors allege that Trump “repeated false claims of election fraud, gave false hope that the Vice President might change the election outcome, and directed the crowd in front of him to go to the Capitol as a means to obstruct the certification proceeding.” To that end, Trump’s “knowingly false” statements during his speech included specific references to his conversations with Pence and continued his pressure campaign on his vice president:

- “I hope Mike is going to do the right thing. I hope so. I hope so. Because if Mike Pence does the right thing, we win the election. All he has to do, all this is, this is from the number one, or certainly one of the top, Constitutional lawyers in our country. He has the absolute right to do it. We're supposed to protect our country, support our country, support our Constitution, and protect our constitution.”

- “States want to revote. The states got defrauded. They were given false information. They voted on it. Now they want to recertify. They want it back. All Vice President Pence has to do is send it back to the states to recertify and we become president and you are the happiest people.”

- In perhaps the most important passage, Trump himself recounts the conversation with Pence, saying, “And I actually, I just spoke to Mike. I said: ‘Mike, that doesn't take courage. What takes courage is to do nothing. That takes courage.’ And then we're stuck with a president who lost the election by a lot and we have to live with that for four more years. We're just not going to let that happen.” Under footnote 3, this passage appears to be a public record of a possibly official act, in which the president openly disclosed deliberations with his vice president concerning another official act.

Can these statements, which include Trump’s own statement about a prior official act, come in?

We could go on, and there are many more questions. For example, the Jan. 6 committee required testimony from a large number of White House, campaign, and vice presidential aides. While these people presumably cannot be made to testify as to their conversations with Trump on immune matters, putting aside hearsay concerns for a moment, can they testify as to the fact of their prior testimony—which is, after all, a matter of public record? And what about the voluminous White House records and other documents the Jan. 6 committee released and that are also now a matter of public record?

Our point, to sum up, is that depending on how the courts interpret the carve-out in footnote 3, it could do anywhere from almost no work to an enormous amount of work for Smith. The words in the footnote offer little hint as to whether there are five votes on the nation’s highest court for a narrow exception to a broad immunity or to an exception that to a large degree swallows the rule.

-(1)-(1).png?sfvrsn=ebd4ed39_5)