What the Heck Happened in Coffee County, Georgia?

A detailed look back at the computer intrusion that features prominently in Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis’s election interference indictment

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Shortly before noon on Jan. 7, 2021, with the nation still reeling from the aftermath of the attempted insurrection in Washington, D.C., a Republican Party official ushers a computer forensics team into an elections office in far-away Coffee County, Georgia.

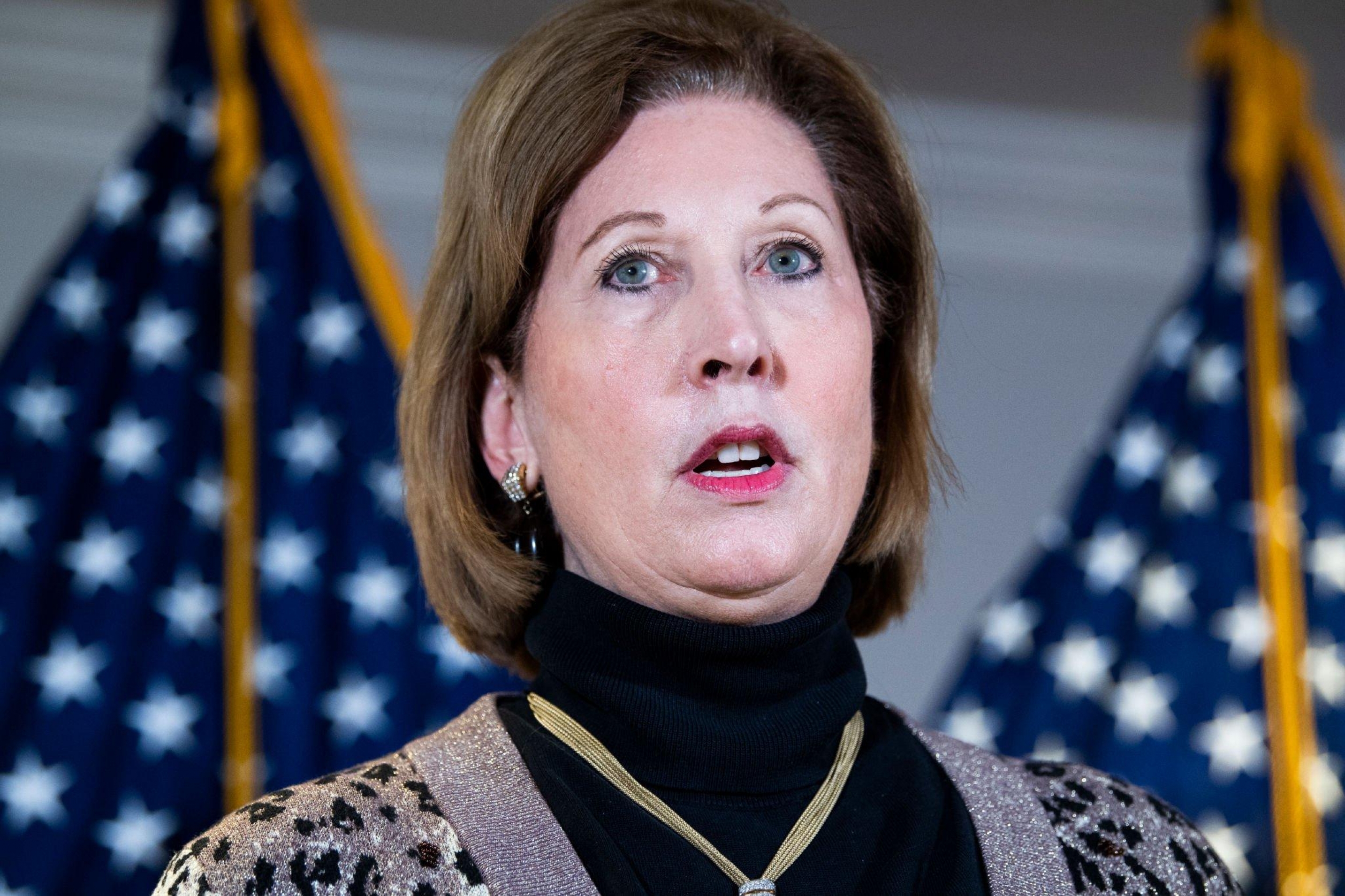

According to a combination of court filings, depositions in subsequent litigation, and the indictment filed Monday evening in Fulton County, Georgia, the forensics team—a group of employees of an Atlanta-based firm called SullivanStrickler—has driven into the rural south Georgia town of Douglas at the behest of Sidney Powell, a lawyer working with then-President Donald Trump’s legal team. They are joined by a man named Scott Hall, a bail bondsman and Republican poll watcher who flew down separately from Atlanta.

Cathy Latham, a public school teacher and chairwoman of the Coffee County GOP, escorts the group inside. There, they are welcomed by two local elections officials, Misty Hampton and Eric Chaney, and a former member of the elections board, Ed Voyles.

Video surveillance detailed in the litigation shows what happens next: Over the course of several hours, the forensics team handles, scans, and copies the state’s most sensitive voting software and equipment. All of this takes place without authorization from any court of law. The elections board will later claim it did not authorize the entry or copying, which the Georgia secretary of state’s office has referred to as “unauthorized access to the equipment that former Coffee County election officials allowed in violation of state law.”

Days before the forensics team sets foot in Douglas, which is about 130 miles southwest of Savannah, voters had arrived at the elections office to mark their ballots in the state’s runoff election for the U.S. Senate, a race that would tip the balance of power in the upper house of Congress. Two months before that, some 15,000 people flocked to the polls in the rural county, as Joe Biden and Donald Trump battled for the presidency. Later, in a recorded phone call entered as evidence in litigation, Hall will claim that the forensics group “scanned every freaking ballot” cast in those races.

“They scanned all the equipment, imaged all the hard drives, and scanned every single ballot,” he will say in March 2021.

Throughout the month of January 2021, similar breaches occur on at least three other occasions, as additional outsiders are again given access to the state’s voting equipment. Forensic copies are subsequently accessed by more than a dozen individuals across several states, the court records show.

Until Monday, no individual involved in the apparent breach in Coffee County had been held accountable. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) has said that it has been investigating the matter for more than a year, prompting questions about the sluggishness of the investigation. An open records request submitted by Lawfare to Coffee County reveals that the GBI recently seized the desktop computer used by Hampton at the elections office—more than two and a half years after the breach. Meanwhile, at the federal level, there have been no public signs that the Justice Department or the office of Special Counsel Jack Smith has taken any steps to investigate the events in Coffee County, despite calls for them to do so.

A separate open records request submitted by Lawfare returned no responsive documents for subpoenas or other communications between Coffee County elections officials and federal law enforcement authorities. A spokesperson for the special counsel’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Yet, just over 200 miles from Douglas, in Atlanta, one prosecutor has taken a deep interest in the events in Coffee County.

In her sweeping indictment handed up on Monday, the Coffee County breach features prominently throughout. Powell, Latham, Hall, and Hampton are all charged under the mammoth indictment’s racketeering charge, which alleges that “several of the Defendants corruptly conspired ... to unlawfully access secure voting equipment and voter data” and “stole data, including ballot images, voting equipment software and personal voter information.” According to the indictment, the “stolen data was then distributed to other members of the enterprise, including members in other states.”

In addition, Powell, Latham, Hall, and Hampton face charges of conspiracy to commit election fraud (Counts 32-33), conspiracy to commit computer theft (Count 34), conspiracy to commit computer trespass (Count 35), conspiracy to commit computer invasion of privacy (Count 36), and conspiracy to defraud the state (Count 37).

The broad outlines, and many of the details, of the events in Coffee County have been reported before, including by CNN, the Washington Post, the Associated Press, 11Alive, and others—all of which have reported on the breach itself and on some of the circumstances surrounding it.

But the account presented in this article—based on public records, depositions, court filings, interviews, internal emails obtained by Lawfare, and the indictment handed up Monday—attempts for the first time to comprehensively detail the extent to which a group of election officials and Republican Party operatives in a small rural county won the ears of the president’s top lawyers and operatives as they sought to discredit the national vote Trump had lost.

It is the story of how, in the name of preventing election fraud, this group appropriated county election systems—and in the process made voting machines there and elsewhere less secure against future attack—and came to be charged with conspiring to commit election fraud themselves.

Powell, Hall, Latham, and Hampton did not respond to requests for comment for this story. Chaney and Voyles, who are not charged in the indictment, also did not respond to requests for comment.

i

It was election night at the White House, and Donald Trump was on the brink of losing the presidency. The Fox News Decision Desk had just called Arizona for Joe Biden, taking the Trump campaign by surprise. Votes around the country were still being counted. But the Arizona call marked a shift in atmosphere at the White House, according to the testimony of former Trump aide Jason Miller before the select committee investigating Jan. 6.

By the early morning hours, Miller said, Rudy Giuliani—the former mayor of New York and the president’s lawyer—was “definitely intoxicated” and espousing conspiracy theories.

“They’re stealing it from us,” Giuliani told the president, according to Miller’s testimony. “Where’d all the votes come from? We need to go say that we won,” Giuliani allegedly said.

Some of Trump’s closest advisers urged a more cautious approach, according to their testimony before the select committee. Bill Stepien, Trump’s campaign manager, told him it was “too early” to call the race. Miller advised him to put off declaring victory until the campaign had a “better sense” of the numbers. Ivanka Trump encouraged her father to tell his supporters that the votes were still being counted.

But Trump sided with Giuliani. Shortly before 2:30 a.m. on Nov. 4, the president delivered remarks from the East Room of the White House, declaring victory even as millions of votes were being counted. “This is a fraud on the American public. This is an embarrassment to our country,” he proclaimed. “We were getting ready to win this election. Frankly, we did win this election.”

In the days that followed, Trump surrogates began to appear on cable TV networks, parroting false or misleading claims about supposed voter fraud or other irregularities. The precise cause of the irregularities varied. It was “suitcases full of ballots.” It was thousands of votes submitted by dead people. And didn’t Hugo Chavez hack the voting machines? Or were the Chinese thermostats to blame? Those in Trump’s orbit seemed convinced that the election had been stolen, yet no one seemed to know how, much less have evidence to prove it.

For many Trump supporters, a key target of suspicion and derision was Dominion Voting Systems, the Colorado-based company that makes election machines and software. On Nov. 10, Powell, a Texas attorney and conspiracy theorist on the then-president’s campaign legal team, appeared on Fox News with host Maria Bartiromo.

“Sidney, we talked about the Dominion Software,” Bartiromo said. “I know that there were voting irregularities. Tell me about that.”

Powell didn’t pause before answering: “That’s to put it mildly,” she said. “The computer glitches could not and should not have happened at all. That’s where the fraud took place, where they were flipping votes in the computer system or adding votes that did not exist.”

There was not then and is not now any credible evidence of widespread irregularities or “flipped” votes for Joe Biden during the 2020 election. And Dominion has repeatedly denied that its machines were manipulated—by Hugo Chavez or otherwise—during the election. Earlier this year, Powell’s exchange with Bartiromo was cited in a defamation suit Dominion brought against Fox News. The suit alleged that the conservative network had aired falsehoods about the voting machine company. In March, Fox settled the suit after a judge granted partial summary judgment to Dominion on the issue of falsity, writing that “the evidence developed in this civil proceeding demonstrates that [it] is CRYSTAL clear that none of the statements relating to Dominion about the 2020 election are true.”

Even in the fog of Trump’s post-election war, federal prosecutors allege that the Trump campaign had reason to believe that many of its claims about election fraud were unsubstantiated. Trump, prosecutors allege in the recent federal indictment of the former president, “spread lies that there had been outcome-determinative fraud in the election and that he had actually won. These claims were false, and the Defendant knew that they were false.”

Indeed, an internal campaign memo, dated Nov. 12, debunked various claims about Dominion machines, concluding that the machines “Did Not Affect The Final Vote Count.” That same day, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) released a statement from election security officials, who called the 2020 election “the most secure in American history.” (Trump fired the director of CISA, Chris Krebs, a week later.)

Still, in the early days after the election, the vanguard of Trump’s post-election legal team—Powell, Giuliani, and L. Lin Wood—were unrelenting. They began to file suits to block the certification of the election in battleground states based on these fantastical and unsupported accusations of widespread fraud. Powell promised to “release the Kraken” of evidence—an apparent reference to the mythical Scandinavian sea monster of enormous size.

In mid-November, a network of Trump lawyers, advisers, and election deniers decamped to Tomotley Plantation, Wood’s sprawling estate in South Carolina. In addition to Wood and Powell, the individuals who assembled at Tomotley during that time included well-known fixtures in the Trump Cinematic Universe. There was Michael Flynn, the former national security adviser who had twice pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI—and to whom Trump would grant a sweeping pardon in December 2020. There was also Patrick Byrne—a prominent election denier, former CEO of Overstock.com, and former paramour of Russian agent Maria Butina.

Others who visited Tomotley were less prominent. The group included Jim Penrose, a former NSA official; Phil Waldron, a retired Army colonel with ties to Allied Security Operations Group (ASOG), the Texas-based cyber intelligence company run by former GOP congressional candidate Russell Ramsland; and Doug Logan, the owner of a cybersecurity firm called Cyber Ninjas.

The team of Trump allies assembled in South Carolina took an early interest in getting “forensic images”—essentially digital copies of data and software of an electronic device—of voting machines in order to support litigation, Logan said in a deposition. As a part of their legal strategy in Georgia and other key states, Trump-aligned lawyers filed motions to access voting equipment for so-called forensic audits. In November, Wood filed an emergency motion in federal court in Atlanta seeking access to voting machines. The effort ultimately failed, as it did in virtually every jurisdiction in which the Trump campaign filed similar suits.

There were, however, minor successes around the country and at least one major exception to the Trump campaign’s string of legal defeats: Antrim County, Michigan.

Much like Coffee County, Antrim is a small, reliably Republican county—of approximately 24,000 people—that found itself embroiled in the president’s efforts to overturn the results of the election. As the Jan. 6 committee summarized the events, the origin of the fixation on Antrim began in the early morning hours of Nov. 4, when an elections administrator in the county, Sheryl Guy, made an error when reporting the unofficial results of the election. Guy’s mistake appeared to show Biden with a substantial lead over Trump—an unusual result considering that Trump was widely expected to win the Republican stronghold. The result was swiftly corrected following an investigation by Guy, which determined that the root of the problem was human error in updating the election counting software. Trump, as expected, won Antrim County by a landslide.

But by the time the error was corrected, the clerical mistake had spawned conspiracy theories about Dominion Voting Systems machines. Trump’s team seized on the narrative, claiming that the incident in Antrim showed evidence that votes had been switched. A local attorney in Michigan, Matt DePerno, sued to get access to the machines. An Antrim County judge issued an order granting permission to the plaintiff’s experts to make a forensic copy of the county’s Dominion machines, as well as the computer system that tallied the votes, according to the committee.

To conduct the work, Powell signed an engagement letter worth $26,000 with an Atlanta-based firm called SullivanStrickler that specializes in collecting forensic copies of computer systems or other electronic devices. In the Fulton County indictment, prosecutors allege that the “unlawful breach of election equipment in Coffee County, Georgia, was subsequently performed under this agreement.” The firm and its chief operating officer, Paul Maggio, had been referred by Penrose, according to a Nov. 19 email provided to Lawfare, in which Penrose writes that he has identified SullivanStrickler “to perform the work if needed in the near term.”

Russell Ramsland, the former GOP congressional candidate turned cyber intelligence expert, subsequently conducted an analysis of the data on behalf of his company, ASOG. On Dec. 14, he released his report to the public. It included the baseless claim that Dominion machines had been infected with a malicious algorithm that manipulated the results of the 2020 election.

Election security experts sharply rebuked the report and debunked its central contention that machines had been compromised. Independent experts for the Department of Homeland Security called it “false and misleading.” Later, a hand recount in Antrim would confirm the results tallied by the voting machines. Still, the president of the United States hyped the report as proof of fraud. “WOW,” he wrote on Twitter the day of the report’s release. “This report shows massive fraud. Election changing result!”

Despite the glaring flaws and baseless claims cited in the Antrim report, its release was a success for Trump, fueling a new wave of outrage among his base. On Dec. 21, 2020, the indictment alleges, Powell emailed the chief operations officer of SullivanStrickler, instructing him to immediately send her team “a copy of all data” obtained by SullivanStrickler LLC from Dominion Voting Systems equipment in Michigan.

But Antrim County wasn’t enough. Trump’s team needed more examples than a single small county in a single state, which alone could not deliver the presidency.

If Trump was going to overturn the election, his allies would need to find a way to access more machines.

ii

On a Tuesday morning in November—approximately one week after Joe Biden won the presidency—the Coffee County elections board gathered to discuss the outcome of the election.

Misty Hampton, the administrator charged with supervising the county’s elections, insisted on the integrity of her own process for adjudicating ballots in Coffee, where Trump won an overwhelming share of the vote. But according to minutes of the Nov. 10 board meeting, Hampton—who is identified as “Ms. Martin” in the minutes and “Misty Hampton AKA Emily Misty Hayes” in the Fulton County indictment—warned of the possibility that bad actors could “manipulate” the state’s voting machines, which were, like those in Antrim County, Michigan, made by Dominion Voting Systems.

She described a process she called “adjudication,” which would in theory allow an elections administrator like herself to change votes on cast ballots. Adjudication occurs when there’s some question about which candidate a person intended to cast his or her vote for. The process involves a “review panel”—usually a three-person panel including representatives from both the Republican and Democratic parties—that reviews the questionable ballots to determine the voter’s intent. An elections administrator then inputs the decision of the panel into the electronic vote counting system. In Georgia, the process applies only to hand-marked absentee ballots, as other ballots are cast using Dominion machines. The integrity of elections depends on whether the human operator in charge of the adjudication process is an “honest person,” Hampton explained. “But the honest person is not in every county.”

Eric Chaney, an elections board member, agreed with Hampton’s assessment of the voting machines. Chaney, a second-generation used car salesman, called the Dominion system “a piece of junk.” He claimed that he didn’t care who won the election, so long as the race was won in a “fair” manner. The minutes report that Chaney said it “SICKENS HIM,” to know that the machines could be used for “fraud.”

Among those in the audience that day was Ed Voyles, who later described himself as a former member of the elections board who had resigned in 2018 after he refused to certify the results of the state runoff that saw Brad Raffensperger elected as secretary of state. Now Voyles urged the board to draft a letter to Raffensperger expressing its “concerns with the system.” Hampton suggested that Voyles—who did not hold any formal position on the board—could draft such a letter.

The board ultimately agreed to send the letter penned by Voyles, according to later deposition testimony. The letter, dated Nov. 11, claimed that the board had discovered “deficiencies in the current Dominion election system.”

During the Nov. 10 board meeting, Hampton created a video in which she purported to demonstrate how a rogue elections administrator could “flip” votes from Donald Trump to Joe Biden during the adjudication process. At one point, the video showed the password to the county’s election management system server, which was displayed on a sticky note on Hampton’s computer. A local news outlet uploaded the video to YouTube, where it racked up more than a quarter million views.

In Georgia, concerns around the integrity of the state’s voting systems were hardly new—and were not the exclusive concern of the Trumpist right. Back in 2017, the Coalition for Good Governance—a nonprofit devoted to election security activism—sued the secretary of state on behalf of a Fulton County resident, Donna Curling. That suit, Curling v. Raffensperger, sought to compel state officials to switch from electronic machine voting to ballots bubbled in by hand. At the time, the state used the “Diebold” machines made by a company called Elections Systems & Software, which provided no independent paper trail to verify the electronic vote count. In 2019, the federal judge overseeing the case, Amy Totenberg, ordered the state to retire its “technologically outdated and vulnerable voting system” ahead of the March 2020 primaries. In the wake of that ruling, the state ultimately settled on the different voting machines made by Dominion Voting Systems.

The Curling litigation, however, was not over. In fact, it has continued, because the plaintiffs are still concerned over the security of state election equipment. One result of the continued litigation has been depositions of many of the actors in the Coffee County saga, depositions that form the basis for much of this account.

While there are genuine issues in dispute in Curling, the issue Hampton raised at that meeting is not one of them. Indeed, vote “flipping” of the type described by Hampton would likely have been discovered during Georgia’s statewide audit later that month, which did not find widespread discrepancies in the vote tally. But in Coffee County, officials were convinced that the election had somehow been rigged. And they were eager to sound the alarm.

The trio of Hampton, Chaney, and Voyles soon began to communicate with Trump staffers and associates. Following the Nov. 10 meeting, Hampton reached out to Robert Sinners, a Trump staffer focused on the campaign’s post-election efforts in Georgia, urging him to request minutes from the board of elections meeting. Complying with that request, Sinners emailed Hampton: “I understand Coffee County voting systems were discussed in detail and I would like to obtain as much information as possible under Georgia Open Records laws,” he wrote. In a deposition, Sinners said that he then forwarded the minutes to Trump campaign attorneys.

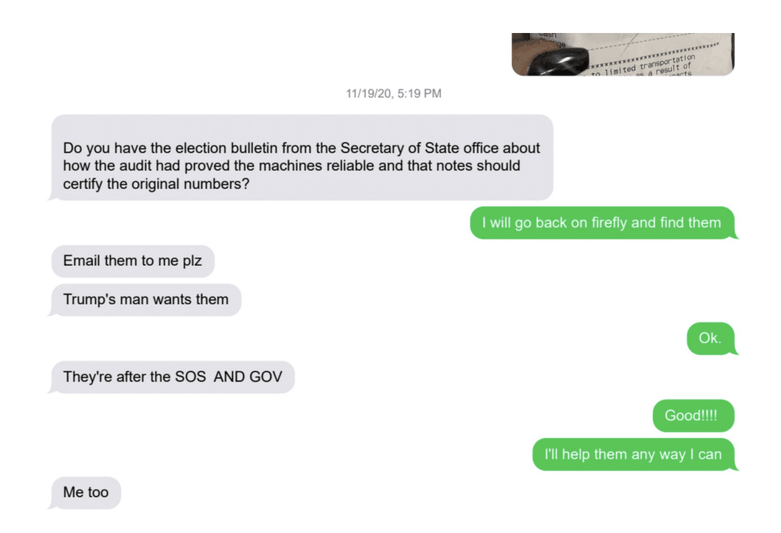

Chaney, the used car salesman who earlier claimed that he “didn’t care who won the election,” also reached out to Sinners. In an email to Sinners describing his concerns with Dominion Voting Systems, Chaney wrote: “THIS IS THE AVENUE FOR FRAUD ON THE LARGEST SCALE IMAGINABLE.” A week later, Chaney asked Hampton to send him a bulletin that had been issued by the secretary of state’s office regarding the reliability of voting machines. “Trump’s man wants them,” he explained in a text message. “They’re after the SOS AND GOV.”

“Good!!!! I’ll help them any way I can,” Hampton replied.

“Me too,” Chaney agreed.

Days later, Georgia held a machine recount of its vote. For a third time, Georgia’s secretary of state certified Joe Biden as the winner of the presidential election. But the Coffee County board of elections refused to certify its machine recount numbers, citing an “inability to repeatedly duplicate creditable election results.” Explaining its decision in a Dec. 4 letter to Raffensperger, the elections board wrote that certification of “patently inaccurate” results “neither serves the objective of the electoral system nor satisfies the legal obligation to certify the electronic recount.”

“Any system, financial, voting, or otherwise, that is not repeatable nor dependable should not be used,” the board told Raffensperger.

The letter did not mention that the “patently inaccurate” results of the county’s recount amounted to a 51-vote discrepancy with its election-night tally—a sum that would have been far from sufficient to alter the outcome of the election in Georgia. Nor did the board specify how problems with the machines could have caused the difference between the counts. And it omitted a critical fact about what actually occurred during the electronic recount: that Hampton had told state elections officials that she was unsure whether she had scanned a batch of ballots twice. The secretary of state’s office launched an investigation, which ultimately concluded that Coffee County’s recount discrepancy resulted from “human error.”

But none of that seemed to matter to the president’s lawyers. By December, Coffee County had captured their attention. The rural county best known for its peanut and cotton fields suddenly became a centerpiece of Trump’s election efforts in Georgia.

On Dec. 12, Kurt Hilbert, an attorney working as local counsel for the Trump campaign, filed suit in state court that sought to decertify the results of the presidential election in Georgia. The plaintiff in the suit was named Shawn Still, who later became the secretary of the Georgia fake electors. The suit, which named both Raffensperger and the Coffee County board of elections, as well as individuals working for the board of elections, as respondents, cited the board’s refusal to certify the electronic recount and the Nov. 11 letter that declared “deficiencies” had been discovered in the Dominion machines. Shortly before the suit was filed, Sinners and another Trump campaign attorney, Alex Kaufman, flew down to Coffee County from Atlanta, and the two collected affidavits from voters at a local steakhouse, according to Sinners’s recollection during a deposition.

Later that month, references to Coffee County also cropped up in other Trump campaign documents. A “strategic communications plan” created by associates of Giuliani cited Hampton’s video that purportedly showed how to manipulate cast ballots on Dominion machines. Two executive orders, which would have directed the Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security to seize Dominion Voting Systems machines, were drafted. The draft orders included identical language noting that Coffee County had “identified a significant percentage of votes being wrongly allocated contrary to the will of the voter” and that “Coffee County Georgia has refused to certify its result.”

Coffee County’s vote-counting woes may not have had merit, but they were useful.

iii

On Dec. 18, three weeks before the breach in Coffee County, a screaming match broke out inside the White House.

Just four days earlier, members of the Electoral College had convened in state capitals across the country to enter their electoral votes for president. A joint session of Congress was set to be held on Jan. 6 to count the electoral votes and declare Joe Biden the winner of the election. In seven battleground states, including Georgia, purported Republican electors had assembled to submit an “alternate” slate of electoral votes for Trump. These “contingent” slates, according to the plan constructed by Trump’s legal advisers, could be used to block or delay certification of the election if Trump won any of his pending legal challenges contesting the election. Alternatively, the false slates could come into play if state legislatures convened a special session to appoint electors who would override the popular vote in the state. If all else failed, Vice President Mike Pence might have been convinced to unilaterally decide to count the Trump slate instead of the Biden slate, or at least use the conflicting slates as a reason to count neither or otherwise kick the issue back to the state legislatures.

Prior efforts to get access to voting machines had largely failed. Powell said the judges who had ruled on Trump’s legal challenges were “corrupt,” according to the recollection of former White House counsel Eric Herschmann. And Powell felt that time was running out to preserve evidence from the machines, she later told the Jan. 6 committee.

It was time for Trump to act.

Powell’s team had a plan: The federal government could seize voting machines in the states under a 2018 executive order. It was an idea that Powell had been mulling before she arrived at Tomotley in late November, ever since she heard the “cyber guys” talk about the prospect of obtaining “hunting licenses”—that is, search warrants—to seize and inspect voting machines, according to her testimony before the Jan. 6 committee.

Days before the Dec. 18 meeting, Powell and others holed up in a hotel in Washington, where they drafted two versions of an executive order that they wanted President Trump to issue that would have authorized the federal government to seize voting machines from the states. One, dated Dec. 16, would have directed the Defense Department to seize state voting equipment. The other, dated Dec. 17, would have directed the Department of Homeland Security to do the same. Both referenced alleged voting irregularities in Coffee County as partial justification for the order.

Last year, emails obtained by Politico revealed that the draft orders were workshopped by multiple people, including Waldron and Flynn. Katherine Freiss, an attorney working with the Giuliani faction of the Trump campaign team; Christina Bobb, a One America News anchor; and Bernie Kerik, an investigator working with the Giuliani legal team, also received emails discussing the draft orders.

On Dec. 18, Powell, joined by Flynn and Byrne, set out the executive order proposal for Trump during an impromptu meeting at the White House, according to the testimony of multiple witnesses before the Jan. 6 committee. In that meeting, she also urged Trump to appoint her as special counsel to investigate voter fraud, according to deposition testimony and the Jan. 6 committee report. This incident shows up as Act 90 of the Fulton County indictment, which alleges that “the individuals present at the meeting discussed certain strategies and theories intended to influence the outcome of the November 3, 2020 presidential election, including seizing voting equipment and appointing SIDNEY KATHERINE POWELL as special counsel with broad authority to investigate allegations of voter fraud in Georgia and elsewhere.”

Other factions of Trump’s inner circle argued against Powell’s plan. According to his testimony before the Jan. 6 committee, Giuliani told Trump that signing the executive orders would be the only thing he ever did “that could merit impeachment.”

Derek Lyons, a former deputy White House counsel who attended the meeting, told the Jan. 6 committee that Giuliani proposed an alternative: “voluntary” access to voting machines. Georgia was a topic of discussion at the time, he said. According to Lyons, Giuliani’s point of view “was that in some way the campaign, I believe, was going to be able to secure access to voting machines in Georgia through means other than seizure.”

Similarly, Powell told the committee that Giuliani said during the meeting that he had a plan to access voting machines in Georgia. But Powell said she wasn’t aware of the details as to how Giuliani planned to get access to machines.

“I think maybe there was an effort by some people to get something out of Georgia, and I don’t know what happened with that, and I don’t remember whether that was Rudy or other folks,” she recalled in her Jan. 6 committee deposition.

A few days later, according to the transcript of Giuliani’s deposition before the Jan. 6 committee, Powell sent an email to Giuliani, Mark Meadows, and Trump’s assistant, Molly Michael: “Also be advised Michigan trip was not set up properly on ground with locals. Team is there with no access. It has cost us great expense that should be reimbursed by Rudy’s funding. Georgia machine access promised in meeting Friday night to happen Sunday has not come through.”

When confronted with this email, Giuliani claimed that he could not remember making such a promise during the Dec. 18 meeting at the White House. But it could be a reference, he said to the Jan. 6 committee, to “negotiating with one of the [elections] boards for access to some of the machines.”

Giuliani also told Jan. 6 committee investigators that, in addition to the court-ordered access they received to inspect Antrim County machines, his team “got access to voting machines” in Coffee County, Georgia.

When asked how he got access to the machines in Coffee, Giuliani clarified that he did not personally have access to the machines. “The people who had access brought the information to us and demonstrated it to us,” he said in his deposition. “They came to me … or they came to our lawyer there who brought them to me—brought them to me, and they showed me their demonstration.”

Giuliani further alleged that an expert who had gained access to the machines in Coffee County gave him a report on it. The person who created the report, he said, was “probably” Phil Waldron—the former Army colonel who was allegedly a primary author of the draft executive order that mentioned voting machines in Coffee County.

Attorneys for Giuliani did not respond to requests for comment for this piece.

iv

Even as the Trump team was looking for voluntary access to voting machines, Coffee County officials were eager to share.

Around the time that members of Trump’s team holed up in D.C. hotels to draft executive orders to seize voting machines, Cathy Latham, then the chairwoman of the Coffee County GOP, also arrived in the nation’s capital, she admitted during her deposition in the Curling case.

Days earlier, Latham had joined 15 other Republicans in a meeting, intended to be secret, at the Georgia state capitol, where participants signed “alternate” Electoral College certificates that purported to award Georgia’s electoral votes to Trump, not Biden. Fulton County prosecutors lay out the circumstances of the fake elector voting in Acts 79-82 of the racketeering charge in Count 1. Latham, Shawn Still, and others also face separate charges relating to this episode. Count 8 accuses them of impersonating public officers. Count 10 accuses them of forgery. Count 12 alleges false statements and writings. And Count 14 alleges a criminal attempt to file false documents.

Within days of that meeting, text messages and deposition testimony suggest, Latham had made her way to D.C.

Why exactly she went to Washington is not entirely clear. At the time, she told at least one source that she was there on matters related to the Coffee County election technology.

On Dec. 17, Marilyn Marks, the executive director of Coalition for Good Governance—the election security organization that initiated the Curling suit—texted Latham. Through the election activism grapevine, Marks had heard about the supposed problems with Dominion machines in Coffee, she said in an interview with Lawfare. Something sounded “suspicious” about it all, she said, but she wanted to learn more. She spoke with elections board member Chaney, who suggested that she get in touch with Latham.

Marks texted the GOP chairwoman, explaining that her organization was involved in litigation to move away from the use of Dominion systems in Georgia. Marks asked when Latham might be available to chat. Latham replied: “I am in D.C. right now and am about to meet with IT guys.”

Latham would later admit under oath that she visited D.C. for an unspecified period sometime in December. But she did not confirm the reason she gave at the time. In her deposition, rather, she claimed that she traveled to the capital city because she had been invited to go on a “tour” by a woman named Juliana Thompson, because Latham hadn’t been able to go the previous year.

“We [got] to see the Christmas trees, and I got to go to the Bible Museum,” she explained.

When asked if she met with anyone who was not with the D.C. tour group, Latham replied, “I’m going to plead the Fifth on that.”

But if Latham was in D.C. only to tour the Museum of the Bible and see Christmas trees, why did she tell Marks that she was “about to meet with IT guys”?

And Latham did admit in her deposition that she stayed at the Willard Hotel during her trip.

“That’s where I slept,” she said.

If the Willard Hotel rings a Jan. 6 bell, that’s because it served as the “command center” for the legal arm of the Trump campaign led by Giuliani in this period of time. The rooms were organized and paid for by Bernie Kerik, the former police commissioner of New York City, who worked for the Giuliani legal team as an investigator. Kerik later sought reimbursement for the rooms from the Trump campaign.

According to his testimony before the select committee, Kerik paid for the room of an unnamed “whistleblower” from Georgia who traveled to the Willard to meet with Giuliani sometime during the post-election period. The “whistleblower,” he said, had been brought to the hotel by William Ligon, a Georgia state senator, and an Atlanta-area attorney named Preston Haliburton. He did not specifically identify the whistleblower by name.

That said, later that month, on Dec. 30, Latham appeared alongside Giuliani and other Trump surrogates at a legislative hearing chaired by Ligon. At that hearing, Latham claimed “whistleblower” status as she testified about the alleged “problems” with Dominion Voting Systems machines that led Coffee County to refuse to certify its machine recount results. Haliburton, who was listed as “counsel of record for the Giuliani legal team,” also represented Latham at the hearing.

Latham, in her Curling deposition, denied that she had ever visited the Willard with Haliburton.

In other words, while Latham has not admitted that she came to Washington and stayed at the Willard Hotel on Kerik’s dime to offer information about Coffee County election machines to the campaign, and while she hasn’t admitted that she was the “whistleblower” of Kerik’s account, she did come to Washington. She did stay at the Willard. She did claim whistleblower status at a hearing chaired by the legislator whom Kerik claimed brought a whistleblower to the Willard. And she was represented at that hearing by the same lawyer who allegedly attended the meeting at the Willard with a whistleblower.

Shortly after her testimony before the Senate subcommittee, Latham received a call from the Atlanta bail bondsman, Scott Hall. He wanted to talk to her about her testimony, Latham said in her deposition during the Curling case. Latham, in the same deposition, denied that the two discussed copying any voting equipment during this call.

Hall, like Latham, believed that something nefarious had gone on in Georgia during the election. On Nov. 17, as Trump’s legal team prepared litigation in Georgia, Hall and his wife, Robin, reached out to Wood, claiming that they had “proof” of voter fraud in Fulton County. “We watched them count boxes of mail-in votes that were 100% Biden and 0% Trump,” Robin wrote in an email to Wood obtained by Lawfare.

On the same day, an attorney named Carlos Silva sent an email to Wood and other lawyers working on Georgia election matters. “Just had a long conversation with Scott Hall,” Silva wrote in an email obtained by Lawfare. “He seems very knowledgeable when it comes to algorithms and other material information that he has on the Dominion voting system that was used in this election. He also has personal knowledge of the fraud that took place and is providing an affidavit.” In another email obtained by Lawfare, Silva wrote to Wood and others that he intended to meet Hall the next morning at the office of Ray Smith, an attorney also charged in the indictment for alleged crimes related to statements he made at Georgia legislative hearings.

Later that evening, Hall’s affidavit was filed as a part of a suit, Wood v. Raffensperger, which sought to halt certification of the presidential election in Georgia. In his sworn statement, Hall alleged that he had personally observed ballots that “appeared to be pre-printed with the selections already made.” “Hundreds of ballots at a time were counted for Biden only,” he wrote.

Hall subsequently became involved with the Trump campaign’s post-election efforts in Georgia, although the nature and extent of his involvement remains unclear. On Nov. 20, David Shafer, the chair of the Georgia GOP, penned an email to Sinners and others, in which he described Hall as someone who was “looking into the election on behalf of the president at the request of David Bossie.” This email shows up as Act 4 in Count 1 of the Fulton County indictment.

The next month, on Dec. 3, Hall testified at a hearing before a subcommittee of the Georgia Senate Judiciary Committee, alongside Phil Waldron, John Eastman, and Russell Ramsland.

By early January, Jeffrey Clark, a little-known Justice Department official who had quickly ascended to Trump’s inner circle in the waning days of his presidency (and was recently named as an unindicted co-conspirator in Trump’s Jan. 6-related federal indictment), had direct contact with Hall, according to the indictment.

Clark, then the acting attorney general for the Justice Department’s Civil Division, had vanishingly little experience with election fraud investigations. But Trump had taken a liking to him after the two were introduced by Rep. Scott Perry (R-Penn.) in mid-December, according to the Jan. 6 committee report and the federal indictment. Within weeks, Clark was being touted as a potential candidate for attorney general amid Trump’s growing discontent with then-Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen.

On Jan. 2, Clark met with Rosen and another Justice Department official, Richard Donoghue, to urge them to send a letter he had drafted to state officials in Georgia and other swing states. The draft letter implored state officials to call a special legislative session to hear evidence on purported election irregularities. And it recommended that the Georgia legislature consider appointing the “alternate” slate of electors that had submitted Electoral College votes for Trump on Dec. 14.

During this conversation, according to Donoghue’s testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, Clark “began to talk about Georgia” and how he had “spoken to this individual in Georgia” regarding allegations of election fraud. The unnamed individual in question is described in Donoghue’s contemporaneous notes as “the largest bail bondsman in Georgia and owns[a] phone company.” According to Donoghue, Clark claimed that the Justice Department had good reason to send the letter to state officials “based on a discussion with this individual in Georgia and things that came up in the Georgia senate hearing.”

Act 110 of Count 1 of the indictment makes clear that this unnamed bail bondsman was, indeed, Hall. According to the indictment, Hall on Jan. 2 “placed a call to JEFFREY BOSSERT CLARK and discussed the November 3, 2020 presidential election in Georgia. The telephone call was 63 minutes duration.”

Meanwhile, back in Coffee County, a Trump attorney named Katherine Freiss messaged an employee of the Atlanta-based forensics firm SullivanStrickler on Jan. 1: “Hi! Just handed [sic] back in DC with the Mayor,” she said. “Huge things starting to come together! Most immediately, we were granted access—by written invitation!—to the Coffee County Systens [sic]. Yay! Putting details together now with Phil, Preston, Jovan etc. Want to give you a heads up for your team. Will be either Sat or Sun this weekend. More soon :)).”

The same day, according to a privilege log produced in a defamation case brought against Giuliani, Friess sent a “Letter of invite from Coffee County GA” to Waldron, Kerik, and Todd Sanders.

A letter of invitation was never produced to the plaintiffs in the Curling litigation. And in an interview with Lawfare, Marks said that open records requests for such a letter produced no responsive documents.

If such a letter does exist, its authority remains illusory. In a deposition in Curling, a representative for the Coffee County Board of Elections said that the board neither knew about nor authorized the operations carried out in January 2021. The secretary of state’s office has publicly referred to the incident as “unauthorized access to the equipment that former Coffee County election officials allowed in violation of state law.”

The indictment does not refer to a letter. It does, in Act 134 of Count 1, allege that on Jan. 6, Latham called Hall and Hall called back. “During at least one of the phone calls, they discussed SCOTT GRAHAM HALL’s request to assist with the unlawful breach of election equipment at the Coffee County Board of Elections & Registration Office in Coffee County, Georgia.”

In her deposition in the Curling litigation, Hampton claimed that Chaney, a member of the board, had directed her to allow the copying of the election systems.

But Chaney would not have had lawful authority to unilaterally direct Hampton to do so, as decisions of the board require a quorum, according to the deposition testimony of the current chair of the Coffee County elections board, Wendell Stone. In that deposition, Stone also said that the board as an institution had no knowledge of the breach.

As details of the breach began to emerge last spring, Chaney initially denied involvement in allegedly unauthorized access to election equipment. “I do not know Scott Hall and, to my knowledge, I am not aware of nor was I present in the Coffee County board of elections office when anyone illegally accessed the server or the room in which it is contained,” he wrote in April of last year, according to a court filing.

When asked in his deposition if he authorized access to the elections office, Chaney invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Chaney did not respond to requests for comment.

v

At 4:17 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2021, the president of the United States belatedly tweeted out his video message to the mob that had forcibly disrupted the counting of electoral votes. “You have to go home now,” he finally said.

But even as Giuliani was keeping up pressure on senators to “slow it down,” Coffee County officials were undeterred.

Nine minutes after the president’s tweet, at 4:26 p.m. that afternoon, Hampton sent a text to Chaney: “Scott Hall is on the phone with Cathy about wanting to come scan our ballots from the general election like we talked about the other day,” she wrote.

The next morning, on Jan. 7, Latham texted Hampton to tell her that the SullivanStrickler forensics team had departed Atlanta and were on their way to Coffee County. Hall, she added, was flying in, too. “Yay!!!!” Hampton responded. These events are also mentioned in Acts 142-143 of Count 1 of the Fulton County indictment.

Several minutes later, Paul Maggio, the chief operations officer of SullivanStrickler, sent an email to Powell, Logan, Penrose, and others. “We are on our way to Coffee County Georgia to collect what we can from the Election / Voting machines and systems,” he wrote, attaching an invoice for SullivanStrickler’s $26,000 retainer fee. The invoice billed Powell’s PAC, Defending the Republic.

Minutes later, Maggio also texted Latham, instructing her to have “Eddie” pick up Hall at the local municipal airport—“Eddie” here being an apparent reference to Voyles.

Last summer, during a deposition in the Curling litigation, Latham claimed that she arrived at the elections office sometime after 4 p.m. She stayed for “just a few minutes,” she replied when queried about how long she stayed inside. Latham also stated that she only spoke to Hall outside the office for “five minutes.”

The indictment alleges flatly, in Act 160 of Count 1, that Latham was lying on these and other points.

And surveillance video from Jan. 7 paints a different picture from her testimony, according to court records. A timeline of the surveillance video created by the law firm Morrison & Foerster on behalf of the Curling plaintiffs states that Latham arrived at the elections office shortly before noon; she then waited outside for Hall and the SullivanStrickler team, escorting them into the building after they arrived. Once inside, she introduced Hall and the forensics team to Hampton, Chaney, and Voyles. The footage shows that Latham ultimately spent more than four hours inside the office as SullivanStrickler employees created forensic copies of virtually every piece of Coffee County’s elections equipment, including the Election Management System (EMS) server, the poll pads, the ballot marking devices, and the ballot scanner, according to court documents.

That afternoon, Maggio emailed Powell: “Everything is going well here in Coffee County GA,” he said, before asking for confirmation of payment.

According to court filings, the forensics team left the elections office around 8 p.m. that evening—well past the usual hours open to the public.

In Powell’s Jan. 6 committee testimony, she downplayed any alleged role she played in efforts to gain access to voting machines. “I think I was asked to pay expenses of some of those trips in some way, some of the teams of cyber people that were going to look for them,” she said. “I didn’t have any role in really setting them up or making sure how they were done that I remember.”

Again, the indictment claims otherwise.

Shortly after the forensics team departed, Chaney sent Hampton a text containing the cell phone number of Sinners, the Trump campaign staffer to whom the two spoke back in November. “Let’s switch to Signal,” Chaney added, referring to the encrypted messaging service.

In his deposition, Sinners denied that anyone had gotten in touch with him about the events in Coffee County. He testified that he had no knowledge of the copying of voting equipment until he learned about it in media reports. “This was well beyond the time that I had disengaged from, you know, the Trump campaign operations,” Sinners said.

Shortly after the events in question, Sinners went to work for the Georgia secretary of state’s office. Last year, he cooperated as a witness for the House select committee investigating the events of Jan. 6. Sinners denied involvement with plans to access voting equipment in Coffee County.

“If your article is factual, then it will be clear that I wasn’t involved,” he told Lawfare when contacted for comment.

Asked if he is cooperating with prosecutors in the Fulton County case, Sinners replied: “I’m not sharing any particulars regarding my own experience at this time. My previous statements should indicate how I feel on Trump’s failure of leadership and the need to speak fully and truthfully to anyone who asks.”

Chaney, for his part, pleaded the Fifth more than 200 times in his deposition, including when asked if he communicated with Sinners about the copying.

The next day, on Jan. 8, Maggio again emailed Powell. “Everything went smoothly yesterday with the Coffee County collection,” he wrote. “Everyone involved was extremely helpful. We are consolidating all of the data collected and will be uploading it to our secure site for access by your team. Hopefully we can take care of payment today.”

Later that month, video surveillance shows that Hampton again permitted outside access to election equipment. Shortly before 5 p.m. on Jan. 18, Hampton arrived at the elections office alongside Logan, the CEO of the Cyber Ninjas security firm, and Jeff Lenberg, a forensic consultant. At the time, the office was closed to the public in observance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. But the surveillance footage shows that the trio spent more than four hours inside the office, according to court filings.

The next day, according to court documents, the surveillance video shows that Logan and Lenberg returned and spent most of the day in the elections office. At one point while Logan and Lenberg were allegedly in the building, Hampton texted Chaney: “The guys measuring my desk are still here,” she wrote.

Over the course of the month, Lenberg made additional visits to the elections office, where the footage shows that he spent time in the room that holds the election management system server.

In respective depositions, both Lenberg and Logan claimed that they were invited to assist Hampton with tests on the voting equipment after she complained of “anomalies” during the Senate runoff held in January. They believed Hampton had authority to authorize the assistance they provided, the men said. And according to Lenberg, neither he nor Logan touched any of the voting equipment; instead, they “directed” Hampton to conduct certain tests.

A month later, on Feb. 25, Hampton resigned from her position as elections supervisor. According to deposition testimony, she signed a letter stating that she had resigned to avoid termination—purportedly on the basis that she fudged her time sheets.

That evening, a private jet owned by Mike Lindell—a prominent election conspiracy theorist, Trump confidant, and founder of MyPillow—appeared on the tarmac at the Douglas municipal airport in Coffee County, according to Hampton’s deposition transcript. The plane had been in Palm Beach, Florida, earlier that day. It stayed in Douglas for about two hours before departing.

Lindell previously told the Washington Post that he was there to meet with entrepreneurs about “cooling towels” that entrepreneurs were pitching to MyPillow.

Within two months, Hampton was hired to run a special election in another rural Georgia county: Treutlen County. This April, 11Alive reported that investigators for the secretary of state’s office had seized the elections server in Treutlen County to check for possible “security compromises” after discovering that Hampton supervised the special election there.

It remains unclear what the secretary of state’s office was investigating or why it seized the Treutlen County servers.

The events in Coffee County may have a long tail. By making voting systems and voter data available, they have potentially made these systems less secure. That issue will still need to be addressed. The indictment, however, at least shows that you can’t—as a county official or a political campaign—just go in and take the stuff without someone noticing and without accompanying legal risk. If you breach election systems to prevent supposed voter fraud, you risk being charged with attempting voter fraud yourself.