What to Watch Post-London

News coverage of the most recent terrorism attack in London has generally tracked predictable story lines: Who were the attackers? Were they inspired or directed by ISIS? What do additional arrests mean?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

News coverage of the most recent terrorism attack in London has generally tracked predictable story lines: Who were the attackers? Were they inspired or directed by ISIS? What do additional arrests mean?

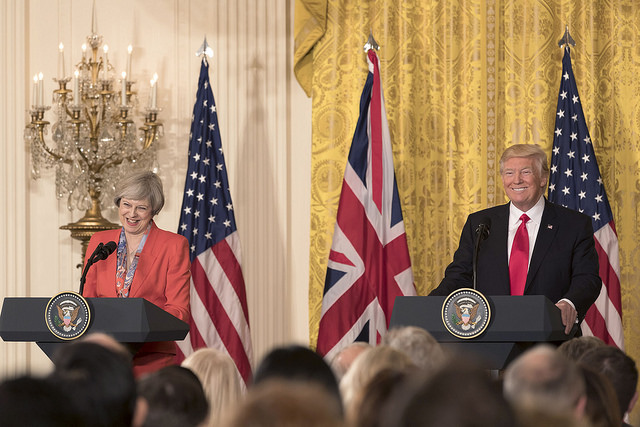

There are also other less predictable (but even more unfortunate) story lines: the President’s rather obsessive tweets about the Administration’s proposed travel ban and his deeply misguided commentary on Sadiq Khan, London’s mayor. And although many have noted Prime Minister Theresa May’s advocacy of a re-examination of British counterterrorism efforts, few have considered closely what such changes might look like—and how they may or may not involve this side of the Atlantic.

In her statement shortly after the events of June 3, the Prime Minister outlined four areas for change: (1) Defeating the ideology—Islamist extremism—that has motivated recent attacks; (2) the regulation of cyberspace to reduce extremism online; (3) reduction of real world safe-havens, both internationally and within the U.K.; and (4) reviewing U.K. government authorities to ensure adequacy to meet the threat. Some commentators have pointed out that the robustness of this outline is in part due to the impending parliamentary election. Although this may have kernels of truth, we should remember that May is not new to counterterrorism, having previously been the longest-serving British Home Secretary in the modern era. And much of what she sketched in her address bears a striking similarity to her earlier initiatives. In this vein, I expect that these will not be fleeting electoral pledges.

The Prime Minister’s first focus, defeating the motivating ideology, is not an inherently new one in the U.K. Since 2003, the U.K.’s counterterrorism strategy (known as CONTEST) has had as one of its four prongs “Prevent,” which focuses on the ideological challenge of terrorism and seeks to use a range of government and NGO resources to reduce radicalization.

But as robustly as Prevent has been funded and pursued by the British government—especially when compared to the U.S.’s anemic efforts—the program has been frequently criticized by many groups. Conservatives have successfully limited Prevent’s programs with certain Salafist elements of the Muslim community. Civil libertarians have repeatedly complained that Prevent programs violate civil rights and stifle free speech. And elements of the Muslim community have argued that the program stigmatizes their communities, is a cover for excessively intrusive law enforcement, and has often created greater mistrust between British Muslims and their government.

All of these criticisms—in addition to others such as the program’s lack of accountability and effective metrics—have some legitimacy, but as a recent Georgetown Security Studies Review noted,

The UK’s CT strategy is not perfect, but it should not be written off as wholly problematic either. The criticisms levied against the Prevent element have merit, but the government has shown itself willing to reevaluate its strategy in order to soften associations with discrimination and assess its effectiveness. These efforts should continue. Counter-radicalization and counterterrorism policies in both the United Kingdom and United States will likely never satisfy all their critics, but paying attention to mistakes, both historical and recent, will do much to level the learning curve.

I thus expect the Prime Minister will seek to re-energize and re-focus Prevent, but it will likely not be a wholesale change given her own responsibility for Prevent during her six-plus year tenure as Home Secretary.

Previous U.S. efforts, for which I was partially responsible during both the Bush and Obama Administrations, have sought to learn from the British and others, but they have tended to be too small and too disjointed. Moreover, many of the most effective efforts must be executed less by “counterterrorism professionals” and more by local and non-government officials who are both closer to the communities in question and less associated with law enforcement and intelligence agencies. We have seen some successes, like those that the Twin Cities has had in engaging its large Somali-American population, but—like the British—we would be well-served by a far more comprehensive review. And critically, it must be done in partnership with the U.S. Muslim community and executed carefully to honor our own Constitutional principles.

Regrettably, it is difficult to muster much if any optimism that the Administration will follow the Prime Minister’s admonition so that we might see a corresponding evolution in U.S. thought, focus, and resources on these issues. Thus far, the Trump Administration’s rhetoric has not gone much beyond the need to use refined nomenclature (i.e., “radical Islamic extremism”). At this point, even getting past the starkly adversarial relationship the President has fostered with the U.S. Muslim community seems like a relatively tall order.

May’s second focus—reducing Internet “safe havens” for radicalization and attack planning—may be an even more challenging space. Again, this is not a new area of focus for the Prime Minister. As was missed by many in the U.S. thanks to our own domestic issues, the Prime Minister sponsored a special session at the most recent G7 meeting on “Digital Policing” so that companies might automatically identify and remove harmful online material, ensure that authorities are notified of such removal, and clarify what constitutes “harmful” material in the first instance. And this is but the latest in the British push, as last Fall, the British Parliament passed the Investigative Powers Act, which requires technology companies to maintain users’ browsing history for at least a year, and Her Majesty’s Government has previously been on the forefront of challenging companies to provide access to online communications.

Similar, albeit less aggressive, activity has also occurred in Washington. Most notably, in 2015 Senators Richard Burr and Dianne Feinstein co-sponsored legislation that would have required technology companies to report terrorism-related activity in the same vein as already occurs with respect to child pornography. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the proposal was met with vociferous opposition by both industry and a wide-variety of issue-oriented groups, which (along with the Obama Administration’s lack of support) led to the bill’s demise. Similarly, while legislative proposals to address the increasing ubiquity of end-to-end encryption and the challenges it poses to law enforcement have bubbled up, none have advanced significantly because of a plethora of legitimate and complex legal, technology, and policy reasons.

The spate of recent attacks in the West, combined with May’s push and a new Administration in the U.S., may change the dynamic in the coming months. Certainly political pressure on both sides of the Atlantic is likely to mount despite some very real improvements brought about by technology companies themselves, thanks to significant investment in policing their user communities. Should May be able to harness the governing and economic strength of the G7 to pressure technology companies without U.S. resistance, a new level of cooperation might be possible. But no one should underestimate the challenges that will continue to exist. Companies are rightfully concerned with user privacy, their own economic well-being, the challenges of a global technology marketplace, and other threat vectors (e.g., cyber attacks) that would be opened by trying to address other challenges associated with terrorism (e.g., end-to-end encryption). It would certainly be worthwhile to review intelligence and law enforcement authority to ensure that we aren’t excessively tying the hands (or confusing the minds) of investigators. Moreover, finding innovative and privacy-protective means to help officials find real needles in the massively overwhelming mounds of haystacks is of the utmost importance. Ultimately, I expect progress might be made in working with companies to even more effectively limit and report worrisome materials, but the security of online communications will be a much harder row to hoe.

Recognizing that physical safe havens continue to be important to terrorist plotting, the Prime Minister next addresses the threats posed by overseas and domestic locations. It is here that May noted the need to face down the “tolerance of extremism” as well as the need to ensure a “truly United Kingdom” as opposed to one composed of “separated, segregated communities.” It is unclear how these efforts might manifest themselves beyond the already-described evolution of the Prevent strategy, but it is undoubtedly important to do so. Like their European neighbors in Belgium, France, and elsewhere the U.K. has pockets of highly isolated, often economically disadvantaged, and culturally torn communities of Muslims. But describing the problem is vastly easier than generating a solution.

Thankfully, the United States has done significantly better on this front. Generally, American Muslims are better integrated, better off financially, from less conservative Islamic traditions, and less focused on international issues than their European counterparts. In short, the American “melting pot” has produced the very benefits for which it has been touted in other circumstances. In this regard, we should ensure that neither our words nor our deeds reverse these invaluable American tendencies and somehow create separations between Muslims and non-Muslims that do not generally exist.

Finally, the Prime Minister notes the need to review Britain’s counterterrorism strategy “to make sure the police and security services have all the powers they need.” In addition to relatively predictable reviews of staffing and budgets (of which the Labour Party has already been critical given the reduction of police officers across the U.K.), we will likely see a review of British pre-charging detention policies as well as of the successor to British Control Orders, now known as Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs). Both have previously been the subject of extensive public debate in the UK, but given the volume of threats now facing British security services, their reform will likely re-emerge as hot-button issues.

With respect to pre-charge detention, U.K. law currently allows for a suspect to be detained for up to 28 days, with judicial review, but without being charged—the longest of any Common Law country in the West. In 2008, the British government’s attempt to extend this period to 42 days was firmly rejected by a broad coalition, with support from some of the U.K.’s most respected former security service officials. Arguably, if the security services are now as overwhelmed as they appear to be, lengthening the pre-charge detention period to allow for greater and more controlled investigation might prove very attractive to the May government.

An independent but related authority, TPIMs allow for the imposition of restrictions on individuals who are suspected of being or having been involved in terrorism when the Crown is unable to prosecute or deport the individual. Adopted in 2011, this authority succeeded the highly-criticized Control Orders, which allowed for significantly greater restrictions, limited review of potentially non-expiring orders. The Control Orders were adopted after the “7/7” terrorist attacks targeting the London Underground and buses, but they were ultimately modified based on significant domestic and external (i.e., European Court of Human Rights) opposition.

Although addressing a different situation than pre-charge detention, the TPIMs would appear to provide a potentially valuable tool to otherwise overwhelmed investigators who—much like their U.S. counterparts, only worse—simply do not have the resources to maintain comprehensive surveillance of every individual who might turn to terrorism. Curiously, however, as recently as October 2016 only six people in all of the U.K. were subject to TPIMs; the reasons for this are unclear given the volume of investigations, but any push for expanding TPIM authorities will certainly have to address why the current tools have been used so minimally.

This foundational challenge—a lack of adequate resources to provide a consistent and reliable monitoring of serious suspects—remains a real one on both sides of the Atlantic. This challenge has been repeatedly highlighted in the U.K. and the United States (and elsewhere), in that numerous perpetrators of terrorism such as the Manchester and Boston Marathon bombers, amongst others, have been on authorities’ radar even if they didn’t appear sufficiently worrisome to dedicate very scarce resources.

It should go without saying that neither pre-charge detention nor TPIMs have a future in the United States given our constitutional traditions. Thus, even if these tools might be helpful to our British partners, they are not ones that can help our still real if admittedly lesser investigative burdens. Post-Boston Bombing reforms that created stronger FBI-State-Local investigative sharing helped our situation, but given federal limitations, it is increasingly important to ensure that our federal agencies are positioned to best use the hundreds of thousands of law enforcement personnel across the country. Doing so will require clear and supportive DOJ and FBI guidelines for such relations, as well as continuing support for federal homeland security funding to State and Local officials on the front lines.

As many have said, the nature of the threat we face today is significantly different from what we countered in 2001 and even 2011. We should continue to review our counterterrorism apparatus because parts are better optimized for the threats of 15 years ago as opposed to today’s circumstances. We must consider what has worked and what we can improve. Critically, we must make sure that such reviews are driven by facts and rigorous analysis as opposed to bombastic rhetoric. And we must both learn from, and work with, our key partners—whether it is our friends in London, or our American Muslim communities here at home.