What’s at Stake in the Austin Waiver

The vote on whether to grant General Austin a waiver is a vote on whether the waiver will be a real constraint in the future.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

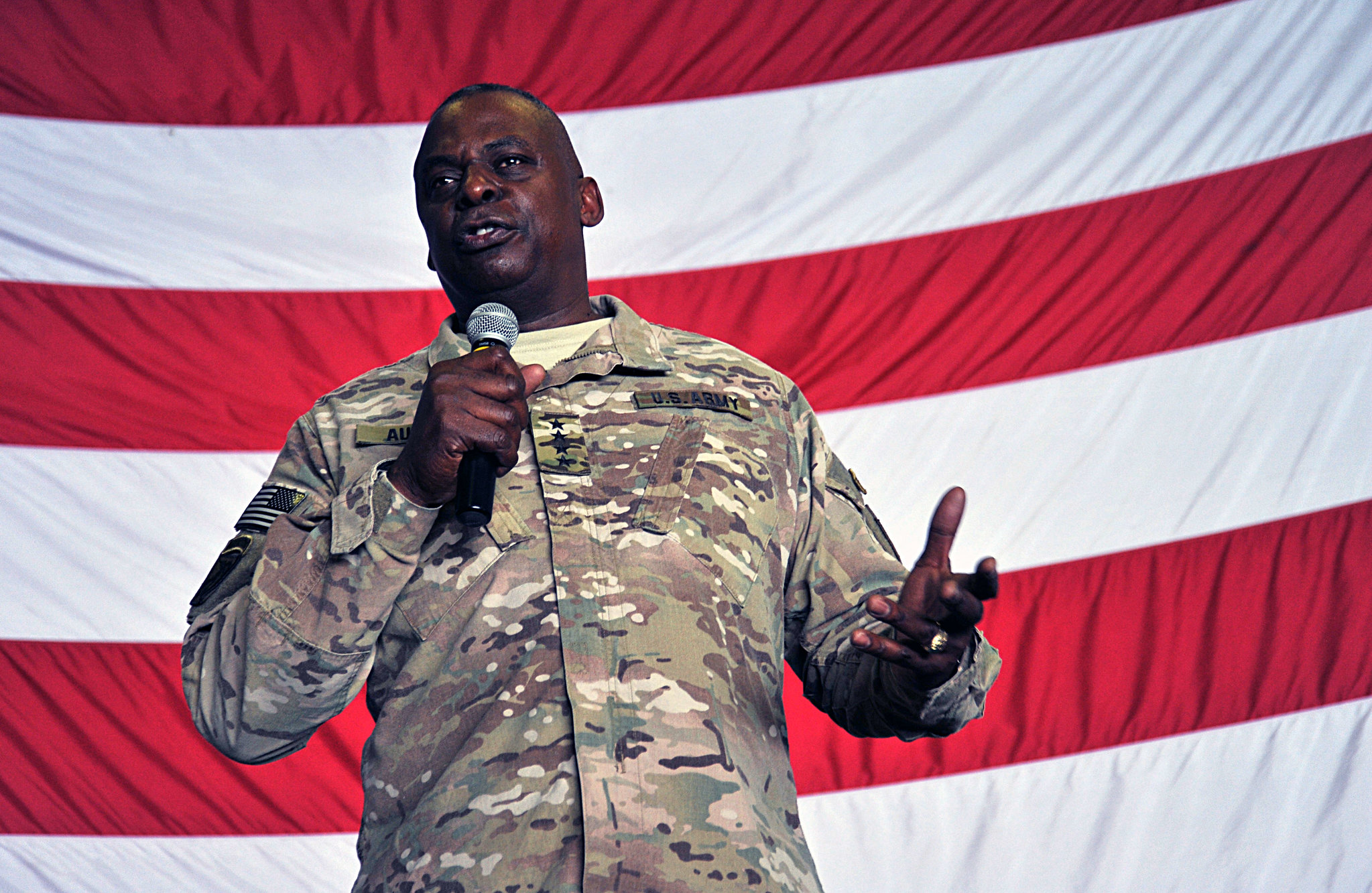

On Tuesday, Jan. 19, the day before President-elect Joe Biden is sworn in, the Senate Armed Services Committee is scheduled to begin confirmation hearings for Gen. Lloyd Austin to be the next secretary of defense. Usually, a Senate hearing is all that’s needed for a Cabinet nominee to be confirmed. But this time, the House of Representatives has a role to play, too—and it will convene its own hearing on Thursday, the first full day of the Biden administration. Because Austin retired from the U.S. Central Command in 2016, both chambers must agree to waive the statutory requirement that the secretary of defense not have served in active military duty within the prior seven years.

While related, the question of Austin’s individual qualifications and the question of granting him a waiver are actually distinct. The jumbled timing of the hearings risks obfuscating the reality that the waiver is the preliminary and independent matter—and the decision with the most significant implications for the future. Similarly, the political dynamics and national security imperatives of a swift confirmation make it tempting to collapse the harder question into the easier one. But the consequences here are too high for Congress or the incoming administration to avoid a frank assessment of what’s at stake. The vote on whether to grant Austin a waiver is, at its core, a decision over whether and how the statutory requirement will act as a meaningful constraint in the future.

The waiver requirement dates back to the National Security Act of 1947, which created both the Department of Defense and the position of the secretary of defense. The original legislation required a 10-year cooling-off period to create a distance between military service and civilian leadership, a period that Congress reduced to seven years in 2008. The purpose was to reinforce the foundational democratic principle that the military is controlled by and accountable to a civilian government, and not the other way around. Congress has waived the statutory requirement only twice before. In 1950, soon after the statute was created, the legislature granted a waiver for Truman nominee George Marshall, a storied Army general who had previously served as secretary of state. In 2017, Congress did so again for Trump’s first secretary of defense, James Mattis, who had retired from active duty in 2013.

Waivers are intended to preserve flexibility while setting particular assumptions—in this case, that a secretary of defense will not be a recent veteran, unless there is a compelling reason. By creating an additional confirmation obstacle for a certain group, the requirement incentivizes the president to select from a different, unencumbered group. This is especially important in the context of the secretary of defense, where members of Congress might be inclined to view recent military service as a qualification for the job, perhaps even a necessary qualification, rather than a deficit. After all, who has more knowledge of the military than someone from its ranks? What better way to earn the trust of the men and women risking their lives in the armed forces? In the face of all this, the waiver requirement intentionally turns recent military service into a liability.

The problem is that the requirement to obtain a waiver functions as intended only when it operates as a substantive obstacle and not merely as a procedural formality. Prior to 2017, members of Congress felt compelled to justify and explain a vote to support a waiver. After reluctantly granting Mattis a waiver in 2017, Sen. Jack Reed, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, vowed not to do so again, saying, “Waiving the law should happen no more than once in a generation.” Given the circumstances of Trump’s election, the outgoing president’s campaign pledges to commit war crimes and the anxieties of U.S. allies in January 2017, members of Congress believed Mattis was a uniquely qualified secretary of defense. Importantly, the qualities that Congress and Trump valued in Mattis in the moment are precisely those that the waiver seeks to disincentivize—that is, that Mattis’s reputation as a thoughtful and aggressive Marine general, and the independent stature of his service record, made him seem particularly qualified to counterbalance and reign in Trump’s worst impulses.

Whatever the merits of granting Mattis a waiver may have been at the time, it is clear in retrospect that granting the exception altered the underlying normative assumptions. This is evident both in Biden’s decision to nominate Austin and in the debate surrounding Austin’s nomination. Indeed, Reed has already softened his “once in a generation” pledge, saying that “[i]t is the obligation of the Senate to thoroughly review this nomination in the historic context it is being presented and the impact it will have on future generations” and that “one cannot separate the waiver from the individual who has been nominated.”

Other members of Congress have been more explicit on the connection. Rep. Ro Khanna told the Washington Post, “Having Mattis get a waiver three years ago and then saying to one of the more qualified African American generals, the first African American secretary of defense, that somehow a waiver doesn’t work for you is hypocritical.”

There is a difference between once in a generation and twice in a generation. There’s also a difference between once in an exceptional circumstance and twice in a row. But beyond that, the fundamental difference between 2017 and 2021 is not between Mattis and Austin, but between Trump and Biden. At the time of Mattis’s confirmation, there were deep and genuinely bipartisan concerns over Trump’s fitness to be commander in chief. These concerns simply don’t exist with Biden. Republicans might disagree with Biden’s policy judgments, but they do not fear, for example, that he might recklessly invite a nuclear confrontation.

If Congress grants Austin the waiver, this will create a precedent that a waiver is justified whenever a president believes the best person for the job is someone who needs a waiver. That is an endlessly malleable standard. At the moment, there is an answer to “Why Mattis and not Austin?” But there will be no good answer to “Why Mattis and Austin, but not this next person?” In the span of four years, the presumption that the secretary of defense will not have recently served in the military will have more or less collapsed.

There are good arguments for still supporting a waiver for Austin, even in light of the precedent it would set. But it is essential that Congress not delude itself into believing that it is possible to make two exceptions in a row and then return to the status quo ex ante. This is a big decision—and it should be made with a frank and clear-eyed assessment of the pros and cons, despite the possible political inconvenience.

So what are the arguments in favor of granting Austin the waiver, despite the larger consequences?

Most fundamentally, a reasonable member of Congress and a reasonable president might just not believe that the rule against recent service is that essential in preserving civilian control of the military—or might believe that it should be a weak rule, rather than a strong one. In this view, the rule is merely one norm of a multitude that reinforces the principle of civilian control over the military, including most significantly a chain of command that reports to the president. After all, there was no confusion that Mattis was a civilian secretary of defense. He didn’t wear a uniform; where his policy judgments conflicted with Trump’s, there was no ambiguity over whose orders the military was compelled to obey.

The seven-year waiting period between serving in the armed forces and leading the Pentagon is arbitrary. It used to be 10 years. It could just as easily be five years, or even four years, nine months, and 21 days—Austin’s distance from service as of Inauguration Day. Certainly, no one is arguing that veterans should be barred from becoming defense secretary. Conversely, no one is endorsing the notion that it would be appropriate for a president to nominate an individual on active duty who would be required to resign to serve, at least not yet. The question is where to draw the line and how bright the line should be wherever it is. Maybe it is enough if the waiver gives the president a slight disincentive to appoint a recent officer and gives Congress an additional point of intervention to debate whether there is a sufficient distance. Maybe it is enough to require that a nominee convince both chambers that he or she intends fully to embrace norms of civilian control.

The Trump administration has altered the traditional norms for former military officers. The 2016 election brought unprecedented willingness of former generals to speak out on behalf of and against candidates. Former Gen. John Kelly served as Trump’s homeland security secretary and then—in an unusual but not unprecedented move—as his chief of staff. And even former officers who remained silent for much of Trump’s presidency eventually reached the breaking point. As president, Trump repeatedly involved the military in political events. And even the active leadership of the services felt compelled to issue implicit rebukes of Trump. Civil-military relationships and public confidence in the military as an apolitical body are in desperate need of repair—but simply reverting to observing traditional norms has an air of magical thinking. A value-based approach to restoration might lead to new rules and new norms, not the old ones that turned out not to hold up as well under strain as we might have predicted.

There are also reasonable arguments that the waiver excessively constrains a president in choosing an essential Cabinet member. The fact that two very different presidents-elect felt compelled to nominate individuals who required waivers may reflect that the prior setup was excluding the best candidates, even as the nation became entrenched in “forever wars” on multiple fronts. And critics have long argued that the current arrangement simply substitutes having a background in the private-sector defense industrial base for recent military service as the presumptive qualification, which carries its own negative consequences. (Though, notably, Austin has also served on the Raytheon board.)

Additionally, as Khanna pointed out, there are consequences to the perception that Congress was willing to make an exception for Mattis, but not on the historic occasion of the first African American nominee to lead the Pentagon. This is especially salient as the nation faces a moment of racial reckoning, and at a time in which there are significant concerns about white supremacists in the military.

So there is a strong case to be made for granting the waiver—but the Biden White House and Austin should be willing to make it directly. The problem is that, thus far, Biden is not making that argument directly nor is the incoming administration publicly grappling with the very real downsides of the appointment.

In an op-ed in the Atlantic explaining his choice, Biden describes Austin as “uniquely matched to the challenges and crises we face.” Yet the notion that Austin is truly uniquely qualified to meet this moment isn’t especially convincing. Austin has clearly won Biden’s trust and confidence, and Biden clearly believes he is the best person for the job. But to justify a waiver, Biden needs to make the case that Austin is the only person for the job—that he is so different from the alternatives that it is worth permanently altering norms surrounding the waiver. Biden’s op-ed fails to make that case. He writes that “[t]he next secretary of defense will need to immediately quarterback an enormous logistics operation to help distribute COVID-19 vaccines widely and equitably.” Austin may be well qualified for this task, but others are too. Biden also writes that “the next secretary of defense will have to make sure that our armed forces reflect and promote the full diversity of our nation.” Austin is indeed a historic choice, but there were reportedly other minority candidates under consideration, as well as the equally historic opportunity to name the first woman as secretary of defense.

Finally, Biden writes that the “next secretary of defense will need to ensure the well-being and resilience of our service members and their families, strained by almost two decades of war. Austin knows the incredible cost of war and the commingled pride and pain that live in the hearts of those families that pay it.” This is a powerful and resonant argument. But it is untrue that those who have served as civilians in the Pentagon and elsewhere are less able to recognize and cherish the sacrifices and experience of U.S. troops and military families. Service members do have unique claims to understanding the experience of war—which is why the waiver requirement is necessary to reverse the natural momentum toward valuing that sacred insight over the other insights that come with distance and perspective.

Still, Austin does have a claim to a unique combination of attributes. A member of Congress who cares deeply about civilian control of the military might look at both the man and the moment and decide to grant a waiver. But it is essential that Congress and the incoming administration use this week’s hearings to directly engage the strongest formulation of the counterarguments.

A seven-year waiting period is not the only thing propping up civilian control of the military, but the points of concern among experts and politicians are not frivolous. After four years of weakened civil-military relations during the Trump presidency, the stakes are higher than ever before. The Department of Defense is under scrutiny for delays in sending National Guard reinforcements during the insurrection at the Capitol after a summer of heavy-handed militarized responses to demonstrations. Biden’s own inauguration is taking place under the protection of thousands of National Guard troops, and the U.S. Capitol is currently encircled by an established “green zone.” And now, in one of his earliest and most consequential decisions in charting the path forward for the U.S. military and the nation, Biden is choosing to double down on Trump’s norm-breaking.

In attempting to persuade Congress, Biden and Austin should engage the terms of debate in a way that consciously avoids starting down a path by which recent military service comes to be seen presumptively as the best, or even the only, qualification for the defense secretary position. They should make the case for where exactly Congress should draw the line on time from retirement—that is, how much time is needed not only to reinforce public perceptions of civilian control but also to avoid incentivizing active officers from auditioning for a political role. And they should be especially careful not to imply that particular military service is an inherently superior qualification, which will increase barriers for women and minority candidates—who are underrepresented in the highest ranks of the military—to be chosen for the top defense position.

Above all, Biden and Austin should approach this moment in the spirit of rebuilding not just norms around military service but also an even more foundational principle: respecting the separation of powers and distinct constitutional roles of the branches. The decision to grant Austin a waiver is an important choice and one that may prove to be a one-way door with unintended consequences. Democrats on the Hill who want to support Biden’s agenda should not shy away from this moment. And Biden and his allies should be willing to embrace a conversation that treats the question of the waiver as distinct from Austin’s individual merits and the historic promise of his nomination.