When Can the President Withdraw From the Open Skies Treaty?

Congress has set limits on U.S. withdrawal from a major arms control treaty. But President Trump may not feel that he has to abide by them.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

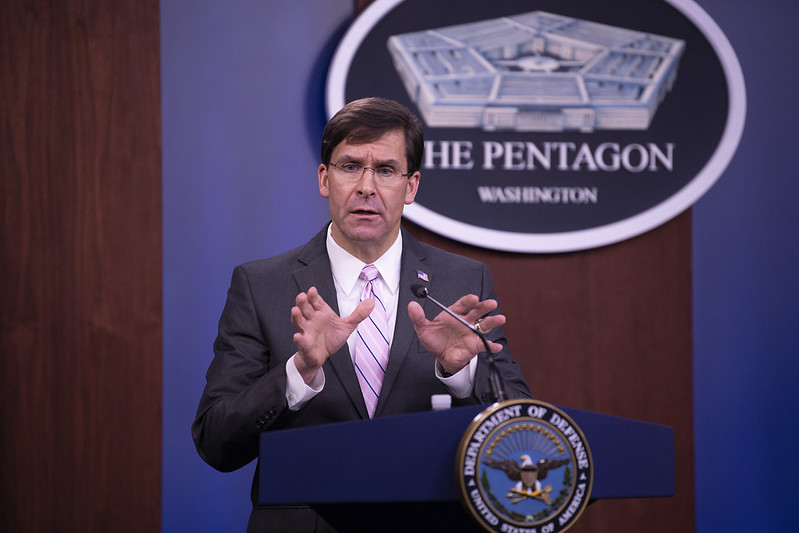

Several weeks ago, in early April 2020, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reportedly agreed to begin withdrawing the United States from the Treaty on Open Skies, a multilateral agreement that facilitates reconnaissance overflights among its members in order to promote military transparency. The Guardian writes that Esper and Pompeo reached this understanding without convening the usual interagency process through the National Security Council—and over the possible objections of others within the Trump administration. Following the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, these efforts may be a sign of President Trump’s ongoing commitment to shedding arms-control-related restrictions. Yet Trump has not yet pursued any consultations or other formal steps toward withdrawal from the Open Skies Treaty, leaving the administration’s next step—and its ultimate intentions—somewhat unclear.

The future of the Open Skies Treaty has been a topic of debate since the Trump administration began to hint that it was considering withdrawal in the fall of 2019. Proponents of withdrawal have argued that Russia is abusing the treaty, which, they say, has become unnecessary in light of modern satellite surveillance. Arms control experts, however, contest these assertions and have continued to defend the treaty as a valuable tool for both the United States and American allies in Europe. Several members of Congress have echoed these latter concerns and urged the Trump administration to engage in “robust prior consultation” before proceeding with withdrawal. As part of recent defense legislation, Congress even imposed several preconditions on initiating withdrawal, including an advance notification requirement that, at this point, would prevent any upcoming withdrawal from being finalized before the next presidential inauguration. But the Trump administration has suggested that it views this requirement as constitutionally invalid in at least some circumstances.

Both Congress’s decision to impose limits on the president’s authority to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty, and Trump’s threat to disregard those limitations, moves both branches of government onto uncertain legal territory. Some observers maintain that the president’s authority to withdraw is exclusive and cannot be infringed by Congress. Yet there are good arguments that Trump may not be able to pursue withdrawal where Congress has legislated to the contrary.

In this case, however, the statutory language adopted by Congress may not be clear-cut enough to force the federal courts to decide the constitutional issue—potentially allowing Trump to move forward without complying with congressional requirements even as the scope of his constitutional authority over treaty withdrawal remains unsettled. If Congress wishes to constrain Trump’s ability to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty with certainty, it should consider enacting clearer statutory limits. That said, the fact that the Trump administration may still feel pressured to comply with congressional requirements underscores the substantial legal and political authority that Congress can exercise over treaty withdrawal when it chooses, even where the specific measures it adopts may not be legally effective.

Treaty Background

The Treaty on Open Skies began as an initiative of President George H.W. Bush, who first outlined the arrangement in remarks at Texas A&M University in 1989. Building on an earlier “Open Skies” proposal by President Eisenhower, Bush saw reciprocal observation flights as a means of promoting transparency around military activities and reducing tensions with the Soviet Union, potentially creating a framework for more sustained peace in Europe. The treaty itself was not finalized until 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union. Yet the Russian Federation and several other post-Soviet states were among its initial signatories, alongside the United States and most of the other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The Clinton administration eventually ratified the treaty on behalf of the United States in 1993, after receiving the advice and consent of the Senate. The treaty itself did not enter into force until 2002 due to substantial delays in ratification by the Russian Federation and a number of other signatories. Yet, pursuant to its terms, several of its provisions began to be provisionally applied shortly after signature. These activities have in turn been coordinated through the Helsinki-based Open Skies Consultative Commission (OSCC), which includes representatives from each signatory.

Under the treaty, parties have the right to conduct observation flights over another party’s territory, using special observation aircraft that meet certain technical requirements—including limits on the types of observation sensors to be used—that are set forth in the agreement. Each party is entitled to a certain number of flights, which must not exceed the number of observation flights that party accepts over its own territory in a given year. An “observing party” must provide three days’ notice to conduct an overflight. Any photographs taken during the flight are shared with all treaty parties—a unique form of information sharing. Implementation is conducted through the OSCC on the basis of unanimous consensus, as the parties (at least until recently) had equal stakes in the successful implementation of the treaty. All in all, the United States and many of its closest European allies benefited from Open Skies over the past several decades.

Article XV of the treaty sets out the terms under which parties may exercise “the right to withdraw.” First, a party must notify the other parties of its intent to withdraw at least six months in advance of doing so. Once this occurs, the state parties, including the withdrawing party, are supposed to convene a conference within 30 to 60 days to discuss the effects of the withdrawal.

Yet this isn’t the only means of leaving the treaty, as customary international law also provides for other exit mechanisms. Most notably, in the event of a material breach by a party to the treaty, customary international law—as reflected in Article 60(2) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties—allows those parties not in material breach to unanimously agree to suspend the treaty in part or in whole, to terminate it, or to terminate it in relation to the breaching party, effectively expelling that party. Alternatively, if a nonbreaching party to the treaty is “specially affected” by the material breach or that breach “radically changes the position of every party[,]” then that nonbreaching party may unilaterally decide to suspend the operation of the treaty in whole or in part in relation to the party that is in material breach. The Trump administration recently relied on this latter remedy to suspend aspects of the INF Treaty in response to alleged Russian material breaches, even before the United States completed its eventual withdrawal in August 2019.

Thus far, no party has asserted material breach in relation to the Treaty on Open Skies. But that doesn’t mean everything has gone smoothly. For several years, the United States has assessed—and other treaty parties have agreed—that Russia is violating the treaty by imposing a 500 kilometer altitude limit on observation flights over the exclave of Kaliningrad, as well as by refusing to authorize flights along Russia’s borders with the secessionist Georgian republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Earlier this month, the United States also asserted that Russia violated the treaty by refusing to authorize a September 2019 U.S.-Canadian observation flight over a Russian military exercise.

Experts have expressed doubts about whether these violations compromise aspects of the treaty “essential to the accomplishment of [its] object or purpose” so as to constitute a “material breach” for purposes of customary international law. Nonetheless, Russia’s actions have been a source of ongoing diplomatic friction. In 2017, the United States began to respond by setting “treaty-compliant” limits on Russian overflights, which led Russia to impose additional reciprocal restrictions of its own. These disputes prevented any U.S.-Russian overflights from taking place in 2018, though flights were able to resume in 2019.

Nor are Russian restrictions the only source of controversy related to the Treaty on Open Skies. American critics of the treaty have also accused Russia of using treaty-backed overflights to gather valuable intelligence on American military installations and critical infrastructure, pointing to Russia’s efforts to seek approval from the OSCC for new types of sensors to be used on planes, an action permitted by the treaty. While experts have disputed whether the intelligence provided by these overflights is superior to what Russia can already secure from satellite surveillance, Russia’s actions have nonetheless led several Republican members of Congress to speak out in support of withdrawal.

Congress’s Position

Since 2014, Congress has regularly inserted provisions relating to the treaty into the annual National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs), setting limits on the availability of funds for various treaty-related activities—including U.S. overflights, technical modifications to U.S. aircraft and sensors, and efforts by the OSCC to change the types of sensors used for overflights—absent certain findings and certifications by executive branch officials. These requirements grew more demanding as the State Department publicly documented Russian noncompliance with the treaty and Russian overflights triggered more congressional concerns. Several of these provisions also reflected a separate debate over the type of military aircraft used for U.S. overflights, which have proved to be expensive to maintain and unreliable in operation but maintain a strong contingent of supporters in Congress.

In the 2020 NDAA, however, Congress took a different approach. Section 1234 of the NDAA lifts prior restrictions on U.S. engagement with the OSCC and reasserts various reporting requirements. More importantly, it sets preconditions on any Trump administration effort to withdraw from the treaty, directing the secretary of defense and secretary of state to “jointly submit” to the congressional foreign affairs and defense committees a notification that withdrawal is in the best interests of U.S. national security and that other treaty parties have been consulted. This notification must be submitted “[n]ot later than 120 days before the provision of notice of intent to withdraw the United States from the Open Skies Treaty[.]” Effectively, this extends the timeline for withdrawal from six to 10 months. If the Trump administration were to try to move forward with withdrawal now, this timeline would delay final withdrawal from the treaty until February 2021, potentially providing the next presidential administration with the opportunity to reverse the decision before it goes into effect. (Separately, Congress also appropriated $41.5 million to repair the aging aircraft used for overflights, further signaling an intent to continue participating in the treaty.)

But it remains unclear whether the current administration sees itself as legally obligated to comply with this adjusted withdrawal deadline. In his signing statement, Trump singled out Section 1234 for comment, stating: “I reiterate the longstanding understanding of the executive branch that these types of provisions encompass only actions for which such advance certification or notification is feasible and consistent with the President’s exclusive constitutional authorities as Commander in Chief and as the sole representative of the Nation in foreign affairs.” While prior administrations have made similar objections to other pre-notification provisions, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the executive views such requirements as invalid in all circumstances or will disregard them. For Section 1234, the practical implications hinge on whether the executive branch views the president’s constitutional authority to withdraw from treaties as exclusive and thus not subject to legislative limits imposed by Congress.

The Trump administration’s position on that issue is unknown. Modern presidents have routinely asserted the authority to withdraw from Article II treaties without input from Congress, so long as the executive does so in a manner consistent with the treaties’ terms or customary international law. The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel at one point asserted that the presidential authority to do so was exclusive—but the opinions containing this view have since been rescinded and the arguments relied on disavowed, though without prejudice one way or another as to exclusivity. That said, nothing prevents Trump from taking back up the legal position that his authority is exclusive, which would allow him to disregard Section 1234 as constitutionally invalid. And if the Trump administration is set on completing withdrawal from the Treaty on Open Skies before his current term in office is complete, that may be exactly what they have to do.

Possible Legal Challenges

If Trump advances this legal position, then he will be entering novel and uncertain legal waters. The Constitution gives quite explicit direction on how the president may enter into Article II treaties like the Treaty on Open Skies: namely, only after receiving the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. (There are other domestic legal mechanisms the United States can use to enter into international agreements, but they are not relevant here.) Yet the Constitution gives no guidance whatsoever on how the United States should exit a treaty. While practice varied during the first century and a half of American history, withdrawal generally took place only with substantial involvement by Congress or the Senate. But in the 20th century, presidents began to assert and act on the authority to withdraw the United States from treaties unilaterally, without input from Congress (to the dismay of some lawmakers). That authority is now widely accepted, at least where withdrawal or other exit mechanisms are consistent with international law.

None of this precedent, however, addresses a situation where a president seeks to withdraw from an Article II treaty contrary to a statute enacted by Congress, as would arguably be the case if Trump were to disregard Section 1234. In such circumstances, the modern Supreme Court generally views executive power as being “at its lowest ebb[,]” meaning the president’s actions should be sustained only where he or she can claim “exclusive presidential control” over the issue. The president may well have an argument that treaty withdrawal is such an authority, as the Office of Legal Counsel’s most recent opinion suggests (without specifically articulating one). But as one of us (Anderson) and other Lawfare contributors have written and discussed in other contexts, the Constitution’s silence on the matter and the mixed historical record make the case for exclusive authority over treaty withdrawal far from airtight. This in turn leaves Congress with a substantial chance of being vindicated on the merits, if a federal court were to reach them.

Whether that will ever happen, however, is another question. Withdrawing from the Open Skies Treaty without complying with Section 1234 may well result in a legal challenge by private plaintiffs, advocacy groups or legislators opposed to the move. But as with many prior challenges to treaty withdrawals, such a lawsuit would face a steep uphill climb on the question of the plaintiffs’ constitutional standing. To establish standing, individual plaintiffs must credibly allege a “concrete and particularized” injury that is caused by the withdrawal decision and remediable by the court—a high bar for broad public policy measures like the Treaty on Open Skies. Members of Congress have been consistently found to lack standing to challenge treaty withdrawals under prevailing Supreme Court precedent. And while individual chambers and committees in Congress have occasionally been found to have standing for pursuing certain types of legal actions—including constitutional challenges to presidential action—that authority has been put into question by a recent appellate ruling and is the subject of ongoing litigation. Congress as a whole might be best positioned to create standing by authorizing litigation on its behalf, either through a concurrent resolution or legislation, but even that remains uncertain.

Moreover, even if a plaintiff is able to establish standing to challenge the president’s actions, that may not be enough. The Supreme Court declined to reach the merits for reasons unrelated to standing in Goldwater v. Carter, a challenge brought by a member of Congress to President Carter’s decision to withdraw from another Article II treaty—and the only case in which the Supreme Court has ever squarely addressed the question of treaty withdrawal. The controlling opinion in that case held that the dispute was not ripe for decision because Congress had not “taken action asserting its constitutional authority” so as to create a “constitutional impasse[.]” A plurality of justices reached the same outcome on the separate grounds that the dispute presented a nonjusticiable political question, a view taken up by several lower courts in subsequent treaty disputes. Subsequent case law has narrowed the political question doctrine substantially by suggesting that “it is emphatically the province and duty” of the federal courts to decide cases “whether [a] statute impermissibly intrudes upon Presidential powers under the Constitution” as here. Yet this effectively brings the political question and ripeness barriers into alignment around the same basic question: Is there a conflict between the statute and the president’s actions?

Here, it’s not clear that Section 1234 creates such a clash. It certainly obligates Esper and Pompeo to submit the required certification 120 days before initiating any withdrawal from the Treaty on Open Skies. But Section 1234 does not expressly prohibit withdrawal until this requirement is fulfilled. In ordinary circumstances, a court might still read its language as implying a prohibition on pursuing withdrawal until the certification is complete. But given the major separation of powers issues at stake—and the heavy hand that constitutional avoidance often plays in statutory interpretation—it seems more likely that the courts would interpret Section 1234’s uncertain language in a way that allows judges to avoid reaching the merits on ripeness or political question doctrine grounds, allowing Trump’s withdrawal to proceed. The irony is that the original version of Section 1234 adopted by the House contained an express prohibition that would have presented a more unavoidable conflict, before it was softened during reconciliation with the Senate.

For Congress, this should prove instructive: If it wishes to have input on treaty withdrawal, then it needs to go beyond simply urging consultation and should instead pick a genuine fight by enacting clearly defined prohibitions and limitations on the president’s authority. And Congress can still do so in relation to the Open Skies Treaty, even if the Trump administration initiates (but does not complete) the withdrawal process. Congress could also authorize litigation on its behalf through legislation, providing perhaps the best chance of establishing some form of congressional standing. Indeed, a bipartisan coalition of senators has already introduced similar legislation to bar exit from another Article II treaty that could provide a good model. (One of us, Anderson, initially proposed this approach in an earlier piece.) Whether Congress will be enable to enact such legislation, however, depends on whether such a bill will receive the support of the two-thirds of both chambers necessary to override a likely veto by Trump—or whether the relevant provisions can be incorporated into timely omnibus legislation, like the next NDAA, that will be more difficult for Trump to veto.

Either way, it may be risky for the administration to ignore Congress’s views on this issue. While Democrats are the strongest supporters of the Treaty on Open Skies, they have been joined by a number of Republicans who may be willing to push to preserve the treaty again—or punish efforts by Trump to withdraw over clear congressional objections. Even if there is not enough congressional support to block withdrawal, Congress could respond by enacting stronger pre-notification and certification requirements in future legislation—including funding cutoffs on administration priorities, a tool that the legislature has used effectively in other circumstances. These tactics may be more costly and difficult for the Trump administration to ignore, raising the question whether the administration values permanent withdrawal from the Treaty on Open Skies enough to risk such consequences and the potential bipartisan opprobrium that may precede them—especially in an election year.

Together, these pragmatic factors and the constitutional ambiguity surrounding the president’s withdrawal authority may lead the Trump administration to choose to comply with Section 1234 instead of evading it. This choice to walk rather than run away from the Treaty on Open Skies would effectively make withdrawal contingent on Trump’s reelection, as it seems unlikely that a Biden administration would be interested in following through. Yet it would also be an acknowledgement of the bipartisan support that continues to exist for many remaining aspects of the United States’s long-standing arms control arrangements like the Open Skies Treaty—and the complications that such support can pose when it manifests as legislation, given the legal uncertainty surrounding the constitutional authority over treaty exit.

Of course, the Open Skies Treaty is not the only arms control agreement on the chopping block: The New START treaty will expire in February 2021 absent renewal. Despite open skepticism on the part of some Trump administration officials, members of Congress have begun to organize in support of keeping New START in place, including through bipartisan legislative proposals that would push for renewal. The legal questions raised by withdrawal from the Open Skies Treaty are entirely different from those presented by New START’s expiration, and it’s not clear that Congress can exercise as much legal authority over the eventual outcome. Yet the ensuing debate over the Open Skies Treaty might help galvanize support for New START and motivate Congress toward action. In this sense, it may lead Congress to play a more active role in securing international agreements that serve U.S. national security interests—stepping in when the president will not.

.png?sfvrsn=48e6afb0_5)