Where the Heck Did the Term 'Collusion' Come From?

On the June 21 episode of Preet Bharara’s podcast, “Stay Tuned with Preet,” a listener called in to ask about the legal meaning of the word “collusion.” Bharara and his two guests were quick to set the record straight; the term collusion, despite it frequent use, has no actual legal definition outside of antitrust law.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On the June 21 episode of Preet Bharara’s podcast, “Stay Tuned with Preet,” a listener called in to ask about the legal meaning of the word “collusion.” Bharara and his two guests were quick to set the record straight; the term collusion, despite it frequent use, has no actual legal definition outside of antitrust law. Instead, Bharara raised a different question for his guests: If collusion has no legal meaning in the context of the Russia investigation, then “why has the word … captured everyone’s attention?” What’s more, how did a word with no legal relevance to the case become so associated with the Trump-Russia allegations?

Bharara and his two guests spent a few minutes tossing around different possibilities. Former White House counterrorism adviser Lisa Monaco suggested that Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s February 2018 indictment charging 13 Russian individuals and entities with conspiracy might have put the concept in play. Former New Jersey Attorney General Anne Milgram brought it back further to Rod Rosenstein’s May 2017 letter appointing Special Counsel Robert Mueller. But the trio failed to come up with a definitive answer, admitting that they just didn’t have a firm sense of where the word came from.

I do.

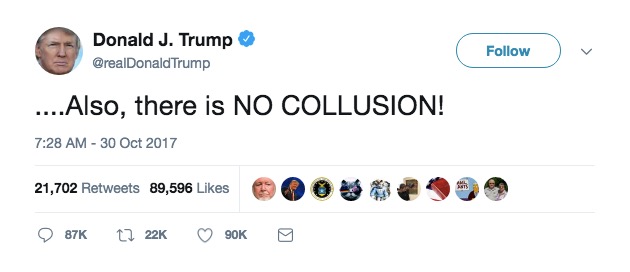

Their conversation prompted me do some digging on the intellectual history of the word “collusion” in the context of L’Affaire Russe, how it got injected into the bloodstream of the conversation, and how it has come to so dominate discussion of Trump-Russia matters that the president can simply tweet “NO COLLUSION!” to convey a huge amount of meaning to his supporters and opponents alike. How did the word “collusion” get introduced into the public lexicon? And who is initially responsible for introducing it? The answer, it turns out, goes back to July of 2016 at the Democratic National Convention.

On July 22, 2016, Wikileaks released more than 19,000 emails from top members of the Democratic National Committee. Two days after the release, Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager Robby Mook told CNN that, according to “experts,” Russian state actors had stolen the emails from the DNC and were releasing them through Wikileaks “for the purpose of actually helping Donald Trump.”

Mook did not use the word “collusion,” but the press, in reporting his comments, did. Within the hour, in an article timestamped at 9:55 a.m., the Washington Examiner reported that Paul Manafort and Donald Trump Jr, had responded to Mook’s allegations and “vigorously denied any kind of collusion between Trump Sr. and the Russian president.” (To be clear, Manafort denied “any ties” between Putin and the Trump campaign, and Donald Trump Jr. criticized Mook for “lie after lie.” Neither one of them mentioned “collusion.”) Ninety minutes later, at 11:27 a.m., ABC News repeated what it termed Mook’s “allegation of collusion between the campaign and Russia.” And three hours later, at approximately 12:35 p.m., Bernie Sanders’s campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, told CNN’s Jake Tapper, “If there was some kind of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian intelligence or Russian hackers, that clearly has to be dealt with.”

From there it was off to the races. Over the next two weeks, the word “collusion” was used hundreds of times by politicians like Martin O’Malley and media personalities such as Trevor Noah.

The term caught on, I think, because it captured the general suspicion that the campaign was somehow in on the hack or knowingly benefiting from it while carefully eliding the fact that no tangible evidence had yet emerged tying the Trump campaign to the Kremlin. (Remember that news of the Trump Tower meeting and other contacts between the campaign and Russian actors had not yet become public.)

After this initial spurt, the collusion frenzy tapered off. Through August and September the word appeared only sporadically in the press, as other stories edged out the Trump-Russia narrative for dominance in the campaign. But when Wikileaks published more than 50,000 emails from Clinton’s campaign chairman in October of 2016, the term had a renaissance of sorts.

The popularity of the term continued to wax and wane throughout the final months of 2016. When a big story would break about Trump, the campaign, or Clinton’s emails, the word “collusion” would appear in headlines. Not every story described the relationship as collusion. Some referred to it as “ties” with Russia. Others questioned whether Trump was “coordinating” with Putin. Collusion had not yet become the de facto term to describe the Russia connection. But it was very much in the mix.

On Dec. 9, 2016, the Washington Post reported that the CIA had concluded that Russia intervened in the 2016 election in order to aid the Trump campaign. Although the Post did not mention the word “collusion” in its article, other media outlets such as the Economist, the Guardian, and CNN included the term when they picked up the story. After that day, the use of the word “collusion” spiked dramatically. It became the universally accepted term to describe any potential relationship between Donald Trump’s campaign and Russia. Even the individuals under investigation bought into the use of the word. In July of 2017, for example, Jared Kushner told reporters “Let me be very clear: I did not collude with Russia.” And in September of 2017, Donald Trump Jr. testified before Senate investigators “I did not collude with any foreign government.”

It’s probably here to stay, despite its being a legal non sequitur. As recently as Thursday morning, President Trump took time out of his day to remind the public that “There was no Collusion.”

Lover FBI Agent Peter Strzok was given poor marks on yesterday’s closed door testimony and, according to most reports, refused to answer many questions. There was no Collusion and the Witch Hunt, headed by 13 Angry Democrats and others who are totally conflicted, is Rigged!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 28, 2018