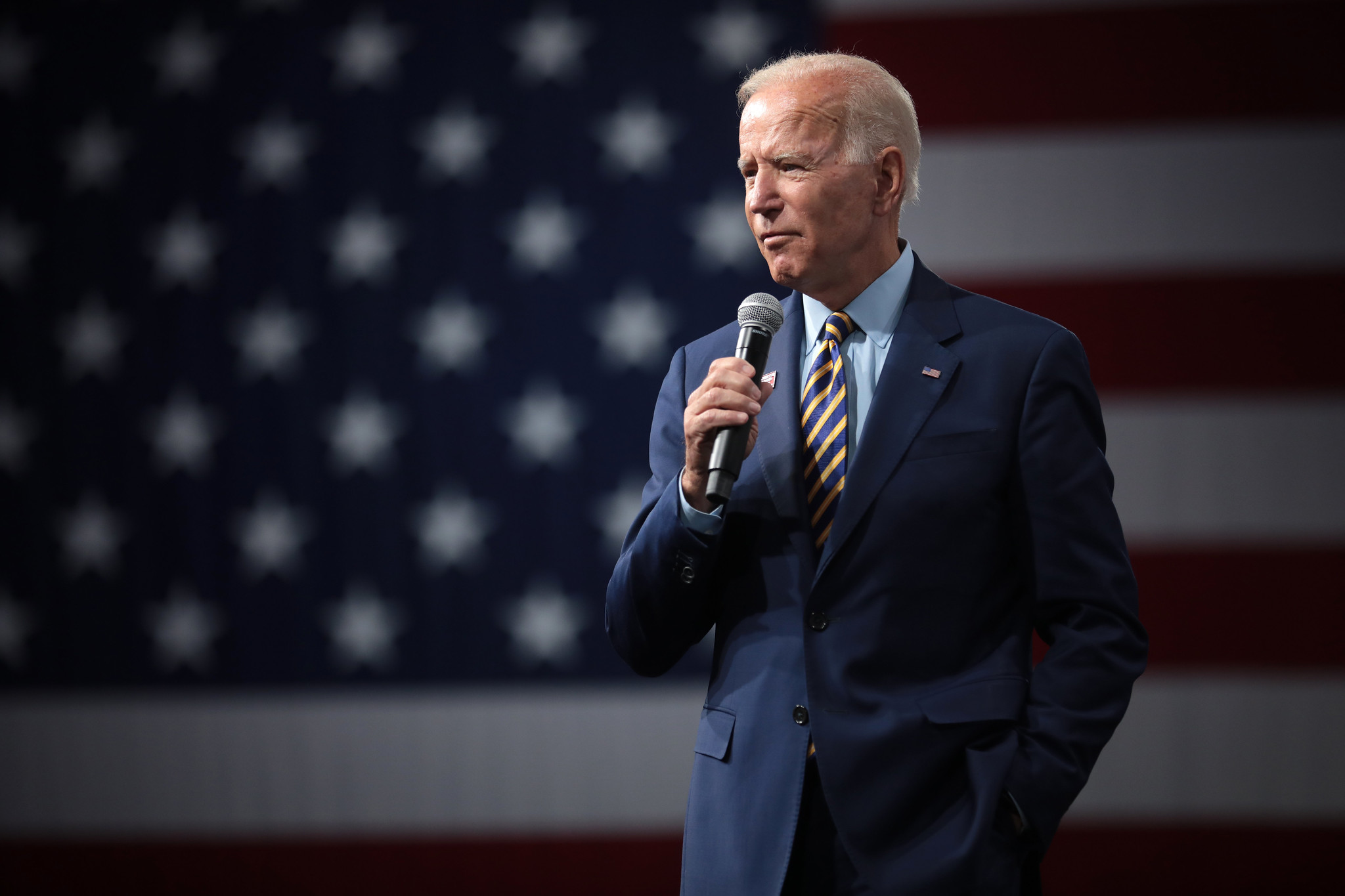

Who Will Decide Whether to Investigate Trump?

Biden would be well within the bounds of law and norms were he to directly instruct the attorney general not to investigate or prosecute Trump or close Trump associates. But he has suggested that he wants his attorney general to make this decision.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

As with other personnel decisions, there has been a steady stream of reporting about President-elect Joe Biden’s search for a new attorney general. Names mentioned include former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, Democratic National Committee chair Tom Perez, outgoing Alabama Sen. Doug Jones, former Department of Justice official Lisa Monaco, former head of the Department of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson and former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick.

Besides traditional considerations—such as the policy fit with the president, management experience, confirmability and demographics—Biden seems to have another, more singular requirement for his attorney general. The president-elect appears to want an attorney general who will decline to criminally investigate or prosecute Donald Trump and his close associates, and who will be credibly seen as having made that decision on his or her own, without direction from Biden. As the saying goes, personnel is policy.

The Department of Justice is an enormous organization with many and varied responsibilities, and the attorney general’s role is correspondingly broad. But Biden’s pick will confront one issue of surpassing importance: whether to criminally investigate and possibly charge Trump, members of his family, or close business or political associates. Relatedly, Biden must also decide who will be the ultimate decision-maker on any investigation or prosecution: the president himself or the attorney general.

Biden would be well within his legal rights, and within the norms of apolitical law enforcement, were he to directly instruct the attorney general not to investigate or prosecute Trump or close Trump associates. The Constitution vests the president with “the executive power,” and directs him or her to “faithfully execute the Office of President” and “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” According to the Supreme Court, “[t]he Constitution requires that a President chosen by the entire nation oversee the execution of the laws.” As I have recently written in a co-authored historical study, the faithful execution duties require—among other things—that the president execute the laws diligently, honestly, impartially, and in good faith for the public good, and avoid self-dealing or other purely privately self-interested actions. These duties have from the beginning coexisted with a good measure of prosecutorial discretion in the president and his subordinates. For instance, as Susan Hennessey and Benjamin Wittes describe, both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson directed that federal prosecutions be dropped for public policy reasons.

Starting around the time of Watergate, and in response to the politicization of the Department of Justice, a set of norms crystallized about the proper roles of the president, the White House, the attorney general and other political leaders at the Justice Department, and career prosecutors and investigators. I attempted to summarize some of these norms as follows:

First, the politically-accountable head of the executive branch—the President—can and indeed should set out the broad parameters of legal and enforcement policy for DOJ prosecutors and law enforcement agencies ... because ultimately the President is accountable for the faithful execution of the law. The Attorney General’s job involves such a large element of sensitive policy—in areas ranging from civil litigation against the government to federal prison administration to immigration to law enforcement priorities—that he or she is properly an at-will employee of the President, and hence responsive to the public will as well....

Partisan political considerations, personal vendettas or favoritism, financial gain, or self-protection or self-dealing should play no role in investigating or prosecuting cases....

Decisions about specific investigatory or prosecutorial steps in particular criminal cases are almost always best left to career officials operating free from political intervention, and supervised by political appointees based only on “law and merit” rather than improper considerations including “White House approval or influence.”

Regarding the president’s role, Hennessey and Wittes describe the norm that “presidents exercise policy control over the Justice Department, but they generally refrain from getting involved in specific investigative matters, which they leave to the appointees they select.” Similarly, Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith describe a post-Watergate “norm” “inhibit[ing] presidential involvement in ... pending investigations.”

But sometimes it can be appropriate for presidents to weigh in on specific criminal investigations or prosecutions. For example, President Barack Obama directed that prosecutions of 10 deep-cover Russian sleeper agents be dropped in 2010 and the spies returned to Russia, as a part of a swap for four people detained by Russia whom the president wished to liberate. There the president’s constitutional and statutory prerogatives over national security and foreign affairs justified overriding the general norm against White House involvement in specific party enforcement decisions. Obama’s action seems consistent with his faithful execution duties, because reasons of state—not corrupt, self-dealing or other self-interested motives—were the apparent motivating factors. Hennessey and Wittes generalize this point, writing that occasionally “broad issues of presidential or national policy hinge on investigative matters,” and that White House involvement with Justice Department prosecution or investigation decisions can be appropriate in those instances.

Although somewhat different legal and prudential considerations are involved, the president’s pardon power also appropriately allows him or her to intervene in specific federal criminal matters to obviate or remit punishment. Perhaps most relevant to the Trump situation, President Gerald Ford issued a blanket pardon to his predecessor, Richard Nixon, for Watergate and any other federal crimes that Nixon may have committed. Although some charged then (and now) that Ford may have made a “corrupt bargain” with Nixon—Nixon would resign and allow Ford, the vice president, to assume the presidency in exchange for a pardon—that does not appear to be true. To justify his actions, Ford cited, in the pardon document and a speech, his desire for national “tranquility” after the nightmare of Watergate; a wish to avoid “prolonged and divisive debate over the propriety of exposing to further punishment and degradation a man who has already paid the unprecedented penalty of relinquishing the highest elective office of the United States”; and concerns about whether Nixon could get a speedy and fair trial. In words that could apply to his forthcoming decision about Nixon—famous words that Biden is probably pondering today—Ford proclaimed, in his speech upon taking the president’s oath of office:

My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over. ... As we bind up the internal wounds of Watergate, more painful and more poisonous than those of foreign wars, let us restore the golden rule to our political process ....

One of Trump’s most flagrant and dangerous norm breaches was his repeated, publicly stated desire that the Justice Department prosecute his real and perceived political enemies—Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, former FBI Director James Comey, former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe and many others. Avoiding any hint of perpetuating this kind of awfulness, so reminiscent of tyrannies and banana republics, is an entirely plausible reason why Biden could want to avert criminal enforcement action against Trump and his circle. In addition to restoring the golden rule of presidents not attempting to jail their political rivals, such a decision by Biden would plausibly serve the public interest by reducing partisan division and hate, and avoiding distraction from his positive agenda on the coronavirus pandemic, the economy and other fronts.

Thus it would be appropriate for President Biden to direct the Justice Department to drop any investigations of Trump or his family and close associates, assuming he were motivated by concerns in the public interest. But Biden has not indicated that he plans to take this path. Instead, insofar as he has announced his thinking on the matter, he seems to want the attorney general to be seen as having made the call to decline criminal enforcement—to buttress the frayed norm of Justice Department independence from the White House on specific party matters, and probably to avoid taking political heat from his left.

Biden has not made an explicit statement on the matter, but he may have already publicly signaled his views on both of these issues. During a Democratic primary debate in November 2019, he was asked whether he would order an investigation of Trump, if elected. Biden responded:

Look, I would not direct my Justice Department like this president does. I’d let them make their independent judgment. I would not dictate who should be prosecuted or who should be exonerated. That’s not the role of the president of the United States. ...

So I would, whatever was determined by the attorney general I supported that I appointed, let them make an independent judgment. If that was the judgment that he violated the law and he should be, in fact, criminally prosecuted, then so be it. But I would not direct it.

In August 2020, Biden told reporters, “I will not interfere with the Justice Department’s judgment of whether or not they think they should pursue the prosecution of anyone that they think has violated the law.” Prosecuting a former president would be “very unusual thing and probably not very ... good for democracy,” he said. But if a criminal case arose, he went on, “then in fact, that would be up to the attorney general to decide whether he or she wanted to proceed with it. I am not going to make that individual judgment.”

And after Biden’s election victory, NBC News reported, “President-elect Joe Biden has privately told advisers that he doesn’t want his presidency to be consumed by investigations of his predecessor.” According to NBC, “Biden has raised concerns that investigations would further divide a country he is trying to unite.” He “believes investigations would alienate the more than 73 million Americans who voted for Trump.” An unnamed Biden adviser also told NBC: “He can set a tone about what he thinks should be done [but] he’s not going to be a president who directs the Justice Department one way or the other.”

One plausible reading of these statements is that Biden does not want a criminal investigation of Trump or people close to him, but that he wants his attorney general to be seen as the one who made this decision. I haven’t seen this reported in so many words—but if my reading of Biden’s public statements is right, it is surely also the case that Biden wants a decision on non-prosecution to be as acceptable as possible to the many people, including Democratic Party leaders and members, who believe that Trump and his associates deserve punishment for any crimes they may have committed.

These imperatives may be in some tension with each other. For instance, a more aggressively left-wing attorney general would have more credibility with the left in the event of declining to prosecute but could be more likely to want to prosecute in the first place. Similarly, the better Biden knows his nominee personally, the more confidence he could have that that person would reach the “right” decision—that is, the decision that Biden wants. But personal closeness to Biden or his team might undermine the public impression that the attorney general made the decision without White House involvement.

Based on the public record, I don’t know enough to speculate usefully about which of the people who have been floated would best fit Biden’s needs. It is possible to say, however, that given Biden’s laudable goal of reducing the appearance and reality of the politicization of the Justice Department—one of the goals that surely influenced his announcement that he would delegate to the attorney general on Trump criminal issues—picking current DNC chair Perez does not seem like a good idea. Becerra, Jones and Patrick also have political backgrounds, though not on the level of a national party chair. Another consideration is that Yates, who was fired as acting attorney general by Trump for insubordination regarding the travel ban, might have to recuse herself from decision-making about Trump were she to get the nod from Biden.

Whomever Biden selects as attorney general, he or she will face a politically difficult situation if the time comes to decide how to handle investigations or prosecution of Trump and his circle. Say that the attorney general decides to forego any federal law enforcement action against Trump. He or she would almost certainly be asked by the press whether Biden or people speaking for him directed this decision. Thus Biden would presumably strive to avoid any overt conversations, much less commitments, on the issue when he is vetting nominees for the position. This is a delicate dance. It will be interesting to see who is chosen for attorney general and what that person has to say about this issue during confirmation hearings and press interviews.

Two caveats in closing. First, I may be overreading the tea leaves. It is possible that Biden thinks criminal enforcement against Trump and his circle would be a bad idea, but that he is genuinely open to the attorney general disagreeing with him and pursuing an investigation or prosecution. Second, Trump may use the pardon power in ways that change Biden’s or his attorney general’s thinking. For example, pardons of Trump’s adult children and the key aides who have the most criminal exposure might make it clear that there is no point in pursuing federal criminal investigations, whatever Biden’s or the attorney general’s personal views might have been otherwise. Alternatively, a Trump self-pardon might increase the chances that Biden or the attorney general considers a criminal prosecution of Trump to be warranted, in order to test and hopefully quash the dangerous and corrupt idea that a president can commit federal crimes in office with impunity.