Who’s Really Crossing the U.S. Border, and Why They’re Coming

Over the past week, the separation of 2,000 children from their parents along the U.S. border has forced immigration into the national spotlight. President Trump, who initiated the separations and then sought to quash criticism with a muddled executive order, has portrayed the policy as a harsh but necessary measure to stop a wave of migrants “bringing death and destruction” into the United States.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Over the past week, the separation of 2,000 children from their parents along the U.S. border has forced immigration into the national spotlight. President Trump, who initiated the separations and then sought to quash criticism with a muddled executive order, has portrayed the policy as a harsh but necessary measure to stop a wave of migrants “bringing death and destruction” into the United States. At another point, he claimed that migrants want to “pour in and infest our country,” linking those crossing the border to the gang MS-13.

Despite what the president says, the situation at the border is much more nuanced. There’s not a flood of people racing across the border. The majority of migrants aren’t dangerous criminals. Many are women and families—and many are fleeing gang violence rather than seeking to spread that violence farther north.

For the past two years, I’ve worked to document these issues at the Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin, and also in the Beyond the Border column for Lawfare—based in part on my fieldwork from across Mexico. There are few straightforward and easy answers to what often feel like basic questions for Central American migration. So it’s worth taking a step back and asking: who are the people arriving at the border? Why are they coming? And how does the current situation compare to migration in the past?

First off, while the current administration has tried to tie Central American migrants to MS-13, government data reveals that gang members crossing irregularly are the rare exceptions. Since the Trump administration took office, the Border Patrol has detected fewer gang members crossing irregularly than during the Obama administration. In FY2017, these detections amounted to 0.075 percent of the total number of migrants (228 MS-13 members out of 303,916 total migrants). When combined with MS-13’s rival, the Barrio 18 gang, the number rises only slightly to 0.095 percent. This is far from the “infestation” of violent gang members described by the president.

The current crisis hasn’t been caused by a sudden influx of migration, either. The peak in apprehensions of irregular migrants actually took place some 17 years ago, in FY2000. At that point, U.S. Border Patrol agents caught 1,643,679 migrants attempting to enter the United States without the appropriate papers, compared to 303,916 apprehensions in this past fiscal year. But this decreasing number of apprehensions should not be confused with a gentler, kinder approach to border security—in fact, just the opposite. Since 2001, the number of Border Patrol agents along the southwest border has nearly doubled from 9,147 agents to 16,605. Border fencing also increased: to date, there are 705 miles of fencing along the 2,000-mile long U.S.-Mexico border.

The face of migration has also changed. Back in 2000, Mexican nationals made up 98 percent of the total migrants and Central Americans (referring to Honduran, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran migrants) only one percent. Today, Central Americans make up closer to 50 percent.

Total U.S. Border Apprehensions by Nationality

Nationality was only made available from FY1995 through FY2017. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, FOIA request.

A declining Mexican birth rate, a stable economy, and the U.S. border buildup have all contributed to the decrease in migration from Mexico. But as Mexican irregular migration has plummeted, Central American migration has simultaneously picked up. Until 2011, Central Americans constituted less than ten percent of total U.S.-Mexico border apprehensions, but by 2012 they constituted 25 percent, and by 2014 they numbered half of all illicit border crossers. While migration from each country within the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) has fluctuated over time, each country has sent roughly similar numbers of people in the aggregate. From FY1995 to FY2016, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended around 500,000 citizens from each country. In other words, it’s not a coincidence that most recent news stories about migrant parents separated from their children feature families from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

Central Americans as a Percent of Total Southwest Border Apprehensions

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, FOIA request.

Yet there’s no one simple description of a migrant. Across the U.S. political spectrum, politicians and activists present Central American migrants as either dreamers or law-breakers; those fleeing violence or those abusing immigration loopholes; crying toddlers or MS-13 gangsters. These labels force migrants into rigid categories, losing the diversity of their reasons and their wide-ranging demographics and backgrounds.

To understand Central American migrants means first abandoning the depiction of the “Northern Triangle” of Central America as a homogenous region. All three countries have different histories and contemporary political realities, along with varying security and development indicators that help explain today’s situation. Using the World Bank’s measure, Honduras has the highest levels of poverty, with 30 percent of the population living at US$3.20 a day or less, compared to Guatemala (25 percent), and El Salvador (ten percent). Meanwhile, two thirds of Salvadorans live in cities, compared to 55 percent of Hondurans and closer to 50 percent of Guatemalans. Finally, Guatemala’s authorities report that 40 percent of the population is indigenous, versus closer to 10 percent in Honduras, and an almost non-existent indigenous population in El Salvador (0.2 percent). These factors help explain what moves migrants from each country to travel to the United States.

Take the following map, which illustrates the hometowns of Central American migrant families apprehended at the border (as reported by the U.S. Border Patrol) from 2012-2017. In Honduras, most families report that they are coming from major cities, such as San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa; the situation is similar in El Salvador, with migrants hailing from San Salvador and San Miguel. This urbanization matters: these cities have high levels of urban gang violence, committed by MS-13 and Barrio 18. These groups have divided control of the cities up into a patchwork quilt and earn the majority of their money from local-level extortion.

Hometowns of Apprehended Central American Family Units

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, FOIA request.

For Central American residents, control of these gangs over their neighborhood likely means a weekly or monthly extortion payment simply for the right to operate a business or live in their territory. The price for failing to provide this money is death. All it takes is a neighbor or nearby shopkeeper to be gunned down for failing to pay the adequate fees, and it becomes clear that the only options are pay or flee. Parents may also send their children to the United States or take them north as the gangs try to recruit them into their activities: Boys of eleven years old (or younger) may be recruited as lookouts and teenage girls may be eyed for becoming the members’ “girlfriends.” Older women who date or at one point dated a gang member can become trapped and unable to escape the violence, with partner-violence a driving migratory factor for many women.

While the gang activities and gender-based violence can empty out neighborhoods, they are not the only factors driving outward migration from these cities. Across the region’s larger cities, LGBT migrants are fleeing discrimination and violence. At a recent trip to a migrant shelter in southern Mexico, I listened as the shelter’s director recounted the story of a father and teenage son who had fled Guatemala City only a few weeks prior: the father was afraid that his son would be killed for coming out as gay. It is not an idle threat. Since 2009, 264 LGBT people in Honduras have been murdered. The La 72 shelter in Tenosique, Tabasco even has a building in the shelter dedicated to providing specialized housing for LGBT migrants.

Among migrants leaving Guatemala, some are fleeing gangs or societal violence in cities, but many migrant families and unaccompanied children come from the Guatemalan highlands, which are more rural, agriculture-based, indigenous, and have lower rates of violence (defined by homicides) than other parts of the country. In asylum proceedings in the United States, women and children from this region frequently cite endemic family and domestic violence, and neglect from the local police who cannot speak their languages or do not answer their phone calls. These areas have also been buffeted by a changing climate, frequent natural disasters, and droughts. And the poverty in these regions leaves residents with little ability for resilience in the face of unpredictable rains or external events.

Without an ability to live safely or prosperously in Central America, residents begin looking to head north to the United States. That means coming up with the US$6,000 to $10,000 necessary for hiring a smuggler. To obtain this money, residents may sell their land or property, rely on the generosity of friends or family in the United States, or borrow money from local loan sharks and leave their farms and property as collateral. This latter option has its own consequences: migrants who use loan sharks and then are detected and deported by Mexican or U.S. officials are unable to pay back the loans, losing their lands in the process and becoming displaced once again.

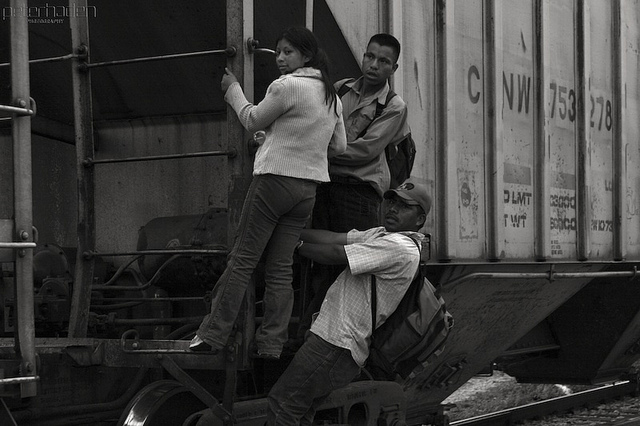

Once the migrants have found a way to raise the money—or if they set out without a smuggler—then they will begin their journey through Mexico. Their mode of transportation and experience will depend heavily on the amount of money that they have, the smuggler’s modus operandi, and whether they plan to seek asylum or try to pass between ports of entry undetected into the United States. Migrants often find smugglers through recommendations from friends and family and they choose between various services on a sliding scale of prices. Migrants with significant amounts of money could choose to take planes to the U.S.-Mexico border and cross in to the country on fake documents; migrants with less money may pay to ride in a trailer through Mexico or take buses through the country; and those without any money at all will walk or ride on the roof of the trains that pass through Mexico.

These routes also change based on Central America’s geography. Hondurans generally enter Mexico closer to the Gulf Coast, Salvadorans enter along the Pacific coast, and Guatemalans enter more frequently through crossing points in between. While the image of migrants riding Mexico’s train network dominates the migration narrative, this is far from the only way to reach the United States. Surveys by researchers from El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF) of Central Americans who were recently deported by U.S. authorities give a sense of these routes’ diversity. In 2017, roughly 40 percent of Hondurans reported riding the train and 40 percent said that they traveled in a tractor trailer at one point in their journey. However, Guatemalan and Salvadoran migrants reported taking these two means of transportation at much lower levels. In fact, only one percent of Salvadorans and eight percent of Guatemalans said that they had ridden the train at any point during their trip through Mexico, and instead reported primarily taking buses through the country.

The journey across Mexico is not, as Trump commented on Thursday, “like ... walking through Central Park.” Migrants are extorted, robbed, assaulted, raped, kidnapped, and murdered at alarmingly high levels and with almost complete impunity. The perpetrators vary by geographic area, including MS-13 and Barrio 18 in the southern part of Mexico (the very gangs that many are escaping); larger criminal groups such as the Zetas and Gulf Cartel in the northern parts of the country such as Tamaulipas; local kidnapping rings and bandits throughout the territory; and even municipal, state, and federal migratory and public security authorities. A 2017 Doctors Without Borders report noted that 68 percent of the migrants that it provided services to in shelters across Mexico had been the victim of a crime during the journey. Women and children are also at particular risk, with nearly one-third of the women reporting that they were sexually assaulted during their trip through Mexico.

And many Central American migrants are female—many more than the Mexican migrants who came before them. While female Mexican migrants averaged around 13 percent of all Mexican migrants apprehended by the Border Patrol from FY1995 through FY2017, Central American women averaged between 20 and 32 percent. In recent years these numbers have increased even more, with women constituting 48 percent of all Salvadoran migrants in the last fiscal year and Honduran women reaching 43 percent of migrants from their country.

Percent of Female Central American and Mexican Migrants

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, FOIA request.

This change is even more dramatic when looking at families and unaccompanied minors. While these groups make up a small proportion of Mexican migrants overall, in recent years, Central American families and unaccompanied children have constituted on average between 40 and 60 percent of the migrants from Central America arriving to the United States. The numbers of unaccompanied children peaked in FY2014 and have since declined slightly, while the number of families arriving at the border—particularly from Honduras and Guatemala—has remained steady.

Apprehended Unaccompanied Minors and Families Along the Southwest Border

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration.

In other words, the families that the Trump administration has focused on separating make up an increasingly high proportion of the migrants who reach the U.S. border.

Previously, many migrants would seek to reach the United States by hiking through the desert undetected. But in recent years, families have begun crossing the border and waiting for a Border Patrol agent, or showing up at ports of entry, to ask for asylum. Before the Trump administration’s recent immigration crackdown, these families would be then taken to a family detention center, where they would have to pass a “credible fear” interview to be released—that is, prove that they have a real fear of returning to their home countries. At least 77 percent of the families pass this hurdle and are released with an ankle monitor or after paying a bond. They can then begin their cases in immigration courts.

The Trump administration is looking to shake up this system. Under the current policy and the June 20th executive order, the administration is pushing to detain families together for months, if not years, while their cases are processed. However, this flies in the face of the Flores settlement, a 1997 consent decree that courts have found to require that children not be detained for more than 20 days. The administration is now seeking to modify the settlement, a gambit that seems unlikely to succeed given the deciding judge’s previous rulings on the matter against the Obama administration.

U.S. Asylum Cases Received by the Executive Office of Immigration Review

Executive Office of Immigration Review, U.S. Department of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/asylum-statistics/download.

At the moment, the Trump administration’s policy is in flux. It’s not clear what will happen if the judge declines to amend the Flores settlement. Yet according to Politico, the administration focus on detaining adults indefinitely has hit it’s own wall—a casualty of insufficient resources on the part of the government. And while the Border Patrol has announced plans to return to their parents the children who are in its custody, there are still thousands of migrant children separated from their parents and families that remain in gut-wrenching uncertainty.

Even in the best of situations, the current arrival of tens of thousands of Central American migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border would bring its own challenges: addressed effectively, it would require rethinking and shifting resources within the United States’ immigration and asylum systems to better process not just single adults but also mothers and fathers with toddlers and teenagers, who are in need of special protections. But despite the administration’s claims to the contrary, the numbers of Central Americans arriving at the border are not near the all-time highs, and there is no infestation or invasion of MS-13. What the data shows instead is something far less dramatic: men, women, families, and children who are arriving to seek safety and the basic American dream of a better life.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)