Why the 2018 Election Season Isn’t Over for the Kurds

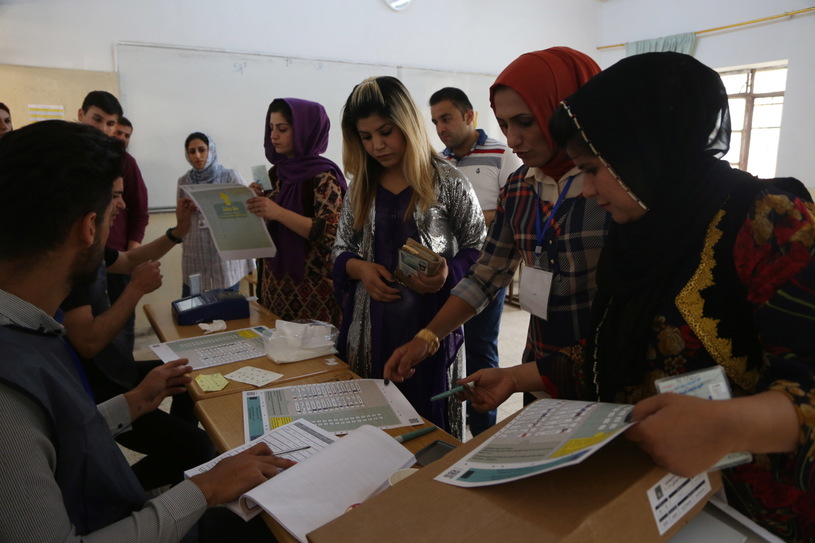

This weekend, Iraqi citizens went to the polls to vote in the first parliamentary elections since the Islamic State seized—and subsequently lost—a third of the country’s territory in 2014.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

This weekend, Iraqi citizens went to the polls to vote in the first parliamentary elections since the Islamic State seized—and subsequently lost—a third of the country’s territory in 2014. For most, the main event has been the intra-Shia competition between Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s Victory Alliance, former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition, and Badr Organization leader Hadi al-Amari’s Conquest Alliance, and what it would mean for Iraqi politics if any garners a stronger share of the votes than expected.

While the election is of critical importance for the trajectory of Iraqi national politics, the stakes are especially high for Iraq’s Kurds, who are looking to undo the damage from the Kurdistan region’s September 2017 referendum on independence. Although the referendum vote was strongly in favor of independence, the Kurds ultimately suffered substantial losses in terms of territorial control, domestic political clout, and international goodwill. The United States and other international allies were angered that the referendum was held despite calls for its postponement, and the Kurds suffered their biggest setback when the oil-rich city of Kirkuk and other Kurdish-held disputed territories were reclaimed by the central government. The referendum has also exacerbated fragmentation within Kurdish party politics. Most notably, one of the two main Kurdish parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), has fragmented with the creation of a new party, the Coalition for Democracy and Justice (CDJ), headed by Barham Salih. A new post-referendum party, the New Generation Movement, has also emerged. Additionally, the parties were not running in the national elections as a united Kurdish alliance. Although the CDJ, Gorran Movement, and Kurdistan Islamic Group are running jointly in Iraq’s disputed territories, all parties are effectively running separately, including the two main parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the PUK.

As a result, Kurdish parties entered the electoral fray more divided and weaker than ever. Although usually described as “kingmakers” in the Iraqi government formation process, the potential of a strong Kurdish brokerage role, which requires a united front among Kurdish parties, has likely diminished.

Yet for all Iraqi parties, the May 12 vote is not the end of a hard-fought electoral season, but the beginning of an intense government formation process—a process that can give weaker parties sometimes disproportionate influence. Iraqi Kurds also have their own regional elections coming up in September 2018. As such, for Iraq’s Kurds, the 2018 election season is far from over, and the aftermath of Saturday’s election can play a large role in what is next for Kurdish regional politics. Here are five reasons why:

Some Kurdish Parties Are Already Rejecting the Vote

Just hours after the polls closed, five Kurdish parties—including the CDJ and Gorran—are already calling for a rejection of the vote and a rerun of the elections in the Kurdistan region. Amid speculation that the PUK made unanticipated gains in the Sulaimaniya area, these parties have accused the PUK of voter fraud and the Gorran Movement has accused its members of attacking its Sulaimaniya headquarters on Saturday night. Piling on, the KDP has also now rejected the results in Sulaimaniya and has called for a manual recount of the votes.

Although the polls have closed and votes are being tallied around Iraq, it may be some time before the election results are themselves settled in the Kurdistan region. It is unclear how this matter will be resolved, but for now Kurdish parties in Sulaimaniya are in an intense standoff over how to move forward.

You Can Lose an Election but Win a Government

Collectively, Kurdish parties are predicted to lose seats in the Iraqi national parliament. And unlike previous elections, the major Kurdish parties are not united behind a single list. A combination of diminished seats in the Iraqi parliament and an absence of collective action will likely diminish Kurdish bargaining power in Baghdad.

However, there are at least two reasons why the Kurds may still make some gains as a result of Saturday’s vote. First, even if Kurdish parties lose seats, they will still represent a non-trivial share of the Iraqi parliament. And in the post-election government formation processes, even small actors and parties can play large roles under the right conditions. Abadi is certainly aware of this and made an unprecedented campaign visit to the Kurdistan region in the run-up the election. Second, and somewhat counterintuitively, having separate Kurdish voting blocs may increase the chances that at least some Kurdish parties are in a winning coalition.

Kurdish Regional Elections on the Horizon

Although the national Iraqi elections are entering their final stage, the regional Kurdish elections cycle is just beginning. On September 30, Kurds will hold their own elections to determine the composition of a new Kurdistan parliament and president. Thinking of May 12 as a first, primary round of voting for Kurds helps explain why Kurdish parties have emphasized intra-Kurdish politics in their national campaign and kept their solicitation efforts close to home.

Additionally, Kurdish parties are using the national elections to more accurately poll the balance of power between Kurdish groups. Prior to the May 12 vote, there was only speculation as to how much support each party held. By using the national electoral results to gauge each other’s real strengths and weaknesses, Kurdish parties can now begin to reassess or fine-tune their electoral strategies for the important local contest in September.

Translating Success in Baghdad to Success at Home

Performing well in May is a good sign of a strong electoral performance in September, but not a guarantee. A lot hinges on how May’s winners and losers play the hands they are dealt in ways that can garner votes at home. The big question after the 2017 independence referendum is whether Kurdish parties will use the referendum’s positive vote to try to exchange Kurdish votes in parliament for Arab support for greater regional autonomy, or downplay self-determination aspirations in order to win a seat in the governing coalition. While the latter approach is more likely and may be more effective in gaining support in Baghdad, it can be a risky approach for gaining votes in the Kurdistan regional elections. Most Kurds remain fiercely nationalist and the post-referendum takeover of Kirkuk in October 2017 by Baghdad has cemented that sentiment. Those parties that are perceived to be cozying up to Baghdad—even if to ensure a Kurdish voice in Iraqi national policymaking—will need to carefully reassert their Kurdish nationalist credentials before the September vote.

September’s Election Determines What May’s Winners Can Do at Home

The parties that performed best this weekend—still yet to be determined—will have more power in national politics and can become an effective conduit for reviving Baghdad-Erbil relations, as well as bargaining, negotiating, and delivering pro-Kurdish deals from Baghdad to the north. This is much needed after the Kurds experienced major setbacks at the hands of Baghdad in the aftermath of the 2017 independence referendum. However, if those successful parties suffer a decrease in support between May and September, or if weaker parties make relative gains in September’s regional election, they may find themselves less capable of delivering bargains made in Baghdad back home. Should different parties hold disproportional influence in Baghdad and Erbil, the respective power centers may ultimately cancel one another out. This may delay a thaw in Baghdad-Erbil relations and heighten an already intense state of competition between the Kurdistan region’s primary political parties.

Overall, it is still too early to tell how these post-electoral dynamics will play out in Baghdad or Erbil. While Iraq’s Kurds may still find a way to salvage a difficult position into moderate gains, the influence of Kurdish parties in Baghdad has clearly been diminished. For Iraqi Kurdish parties, however, the most important vote is still to come.