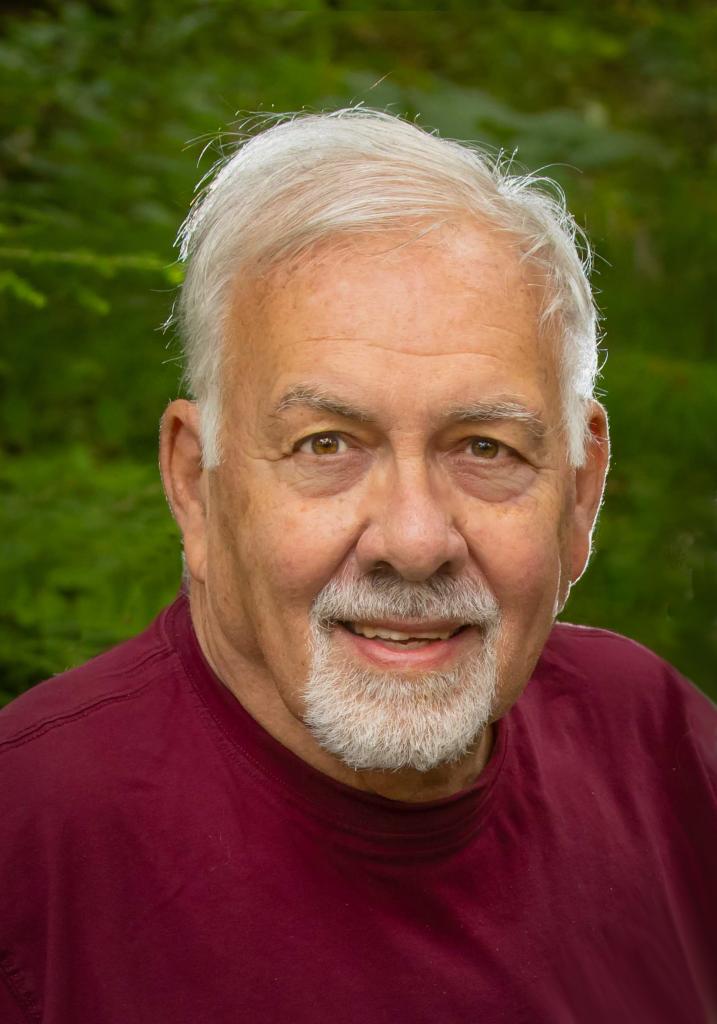

Why Hasn’t the Justice Department Charged Mark Meadows With Contempt?

It’s been four months since the House asked the Justice Department to seek Meadows’s indictment. Are the department’s misguided precedents holding things up?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Four months have passed since the House of Representatives found former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows in contempt and asked the Department of Justice to bring his case before a grand jury. The department has yet to respond. When the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol recently voted to hold in contempt two other former White House advisers, Peter Navarro and Dan Scavino, committee members grumbled about the delay. One said the select committee was doing its job and “the Department of Justice needs to do theirs.” Another declared: “The Department of Justice has a duty to act on this referral and the others we have sent. Without enforcement of its lawful process, Congress ceases to be a co-equal branch of government.” A third pleaded: “Attorney General Garland, do your job so we can do ours.” Might the attorney general, like Hamlet, still be agonizing about his decision? (A delay of only three weeks before seeking the indictment of Steve Bannon prompted “widespread exasperation” with the department, prompting Jonathan Shaub and Benjamin Wittes to discuss possible reasons for the delay in this Lawfare post.)

The Justice Department’s decision isn’t easy. And, bluntly, a key issue is whether to adhere to an unfortunate line of decisions by the department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) or instead follow the law. A second issue is whether the OLC rulings might have misled Mark Meadows by indicating erroneously that he was entitled to disregard a subpoena to appear before the committee.

The Department’s Recognition of Testimonial Immunity in Cases Like Meadows’s

When Meadows disobeyed the select committee’s subpoena, his claim that executive privilege would permit him to decline to answer many of the committee’s questions looked promising. The committee itself didn’t dispute this claim. It noted only that claims of executive privilege must be judged in the context of specific questions and that the privilege plainly wouldn’t apply to some of its queries. Following the House’s contempt citation, Meadows filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court asking it to provide “much needed clarity” by determining the validity of former President Trump’s claim of privilege in a related case. The court’s prompt ruling, Meadows said, would guide his dealings with the committee and could narrow or eliminate the need for further litigation.

Litigants should be careful what they wish for. As a Lawfare post by Elizabeth McElvein and Benjamin Wittes explains, the court soon eliminated any possibility that Meadows or other witnesses could successfully invoke executive privilege in response to any of the select committee’s relevant questions. Before declining to review a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, the Supreme Court declared that only one part of this decision was binding precedent—its conclusion that Trump’s claim of privilege failed every possible test. The appellate court concluded that, whatever the standard might be, the select committee’s “uniquely weighty interest in investigating the causes and circumstances of the January 6 attack” outweighed the interest in preserving the confidentiality of presidential communications. The Supreme Court’s denial of review ensured that, for the duration of the select committee’s investigation and beyond, this decision would supply the governing law of executive privilege in the only jurisdiction where litigation concerning that privilege was likely to arise.

But Meadows made a supposedly distinct claim that neither the D.C. Circuit nor the Supreme Court had considered—that he was entitled to a “longstanding testimonial immunity for senior advisors to the President.”

Testimonial immunity is appropriate when a witness is privileged not to answer any question a court or investigating body might ask. For example, a prosecutor wouldn’t call a criminal defendant as a witness unless her testimony would aid the prosecutor’s case (that is, be incriminating), and, because the defendant is privileged not to incriminate herself, she need not take the stand. But when the applicability of a privilege depends on the specific questions asked and when the privilege is qualified rather than absolute, affording a privilege not to show up makes little sense. And when a witness has no legitimate claim of privilege at all and her appearance wouldn’t interrupt the performance of any official duties, testimonial immunity becomes still more farcical. Allowing Meadows to disregard a subpoena wouldn’t advance any public interest, and only one thing keeps his claim from flunking the laugh test: OLC precedents support it.

Meadows cited five OLC rulings (but no judicial decisions) in support of his claim, and the most recent of these rulings appeared to be on point. It declared that former White House Counsel Don McGahn could lawfully disregard a congressional subpoena even if his testimony would be unprivileged. The House contended that President Trump had waived executive privilege, but OLC opined: “[T]he question whether an adviser need comply with a subpoena ... is different from the question whether the adviser’s testimony would itself address privileged matters.” In support of its claim of immunity, OLC cited 14 Justice Department documents (opinions, letters and memoranda). Officials serving under eight presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, had signed these documents. Like Meadows, however, the OLC opinion cited no judicial opinions recognizing testimonial immunity because there were none.

The Courts’ Rejection of the Department’s Position

One district court decision had rejected the OLC position before OLC extended this position to a ridiculous extreme in McGahn’s case. In an earlier case, OLC concluded that Harriet Miers, a former White House counsel to President George W. Bush, was entitled to disregard a House subpoena. The House then sought judicial enforcement of this subpoena, and the Justice Department, representing Miers, asked the court to recognize her immunity from being required to appear.

Judge John Bates, who had been appointed to the bench by the same president Meirs advised, rejected the department’s arguments and ordered Miers to comply with the subpoena. If the department’s position were to prevail, he noted: “Congress could be left with no recourse to obtain information that is plainly not subject to any colorable claim of executive privilege.” He wrote that the department’s position was “virtually foreclosed by the Supreme Court” and quoted a statement of the Supreme Court in the Nixon tapes case: “[N]either the doctrine of separation of powers, nor the need for confidentiality of high-level communications ... can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity.”

In its McGahn ruling, OLC “respectfully disagree[d]” with Bates’s decision and “adhered to this Office’s long-established position that the President’s immediate advisers are absolutely immune from compelled congressional testimony.” So the House again sought judicial enforcement of its subpoena, the Justice Department again presented its claim of absolute immunity, and the department lost again. Judge Kentanji Brown Jackson wrote: “[T]he proposition that senior-level presidential aides are entitled to absolute testimonial immunity has no principled justification.” The judge added that this proposition is “overbroad,” imposes “unwarranted societal costs,” serves “only the indefensible purpose of blocking testimony about non-protected subjects,” has “no basis in law,” cannot “be squared with core constitutional values[,]” and appears to be “a fiction that has been fastidiously maintained over time through the force of sheer repetition in OLC opinions.” It was true that one official in England couldn’t be required to testify, but “the primary takeaway from the past 250 years of recorded American history is that Presidents are not kings.”

Recent Supreme Court decisions are also in tension with OLC’s claims. In 2020, in Trump v. Vance, the court held that President Trump was obliged to comply with a subpoena for personal documents issued by a state grand jury. The court’s opinion began: “In our judicial system, ‘the public has a right to every man’s evidence.’ Since the earliest days of the Republic, ‘every man’ has included the President of the United States.”

Vance concerned the president’s duty to provide evidence in judicial proceedings. In Trump v. Mazars, the court held that Congress must satisfy a tougher test than a court to obtain personal papers from the president. Again, however, the court left no room for absolute immunity. Quoting an earlier opinion, it italicized one word to emphasize the president’s obligation: “When Congress seeks information ‘needed for intelligent legislative action,’ it ‘unquestionably’ remains ‘the duty of all citizens to cooperate.’”

Conflicts and Perceived Conflicts

The Justice Department, part of the executive branch of government, has a conflict of interest whenever it renders an opinion about a legal dispute between the executive branch and Congress. The magisterial style of OLC opinions hasn’t concealed their home-team bias.

A second potential conflict of interest may haunt the department as well. The officials favored by its precedents have been not only officers of the same branch of government as the attorney general and the president but also members of the same political party. And the officials investigating their conduct, seeking their testimony, and trying to make them look bad nearly always have belonged to the other party. Investigations of alleged misfeasance by the party in power seem to occur only when the other party controls one or both houses of Congress. Every tilt in favor of the executive branch also has been a tilt in favor of the president’s party.

The House’s January 6 investigation presents a rare departure from this pattern. The House and the Justice Department are controlled by the same party, and the House is investigating (among other things) the conduct of a former president of the other party. With this configuration, the department’s potential biases are no longer linked. The department’s overall bias might have shifted from protecting executive officers (and former officers) too much to protecting them too little and prosecuting them too often. Emphasizing that there cannot be “one rule for Democrats and another for Republicans,” Attorney General Garland has stressed that the Justice Department must remain nonpartisan.

The legal positions of a nonpartisan Justice Department shouldn’t shift with the outcome of each election. But when the department hasn’t always been nonpartisan and when some of its positions are contrary to law, the correction of these positions should have a higher priority.

The Justice Department could give its claims of testimonial immunity a decent burial (more decent than they deserve) without disparaging them. It could note only that the state of the law has changed and that claims of absolute testimonial immunity are now unlikely to succeed in court.

The Justice Department doesn’t regard a district court ruling as controlling (not even when its author is named Jackson and will soon be a justice of the Supreme Court), but it does consider a district court decision’s persuasive force. And two district court decisions rejecting and denouncing its position (Jackson’s and Bates’s) are more persuasive than one. (It would be odd if the Justice Department weren’t persuaded by the best-known decision of a confirmed Supreme Court nominee chosen by the same president who chose the attorney general.) In addition, the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in Vance and Mazars undercut the department’s position.

Although the Justice Department’s abandonment of its immunity claims would be nonpolitical and meritorious, opponents could portray its move as something else. Imagine this hypothetical howl from members of the other party:

Attorney General Garland has cast aside an unbroken line of Justice Department precedents that other Attorneys General of both parties honored for fifty years. This string of decisions began with an opinion of Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist in 1971 and was reconsidered and reinforced by Justice Department opinions in the Reagan, Clinton, and Obama administrations. Something changed between the time the Department recognized the testimonial immunity of Don McGahn in 2019 and the time it denied the testimonial immunity of Mark Meadows in 2022—the identity of the party in power and the appearance in its sights of a prominent former official of the other party.

To be sure, the top administration of the Justice Department wasn’t the only thing that changed after 2019, and both the legislative and the judicial branches of government have been as consistent in rejecting the executive branch’s claims as the executive branch has been in asserting them.

To Charge, or Not to Charge, That Is the Question

Here’s the dilemma: Should the Justice Department adhere to its bad precedents, conclude that Mark Meadows had no duty to appear before the select committee, decline to seek an indictment, and be prepared for one kind of howl? Or should it abandon its precedents, seek an indictment, and be prepared for the other kind of howl?

Or should it do neither? It could take an in-between path—abandoning its unfortunate precedents and also declining to prosecute Meadows. The Justice Department might decline to seek an indictment, not because Meadows’s conduct was lawful, but because its own precedents could have led him to believe he had a privilege not to show up. This Solomonic solution would reveal that the department, far from grinding a political ax, sometimes can be magnanimous.

Many state criminal codes provide a defense of “mistake of law” when an actor has relied reasonably on a government agency’s determination that her conduct would be lawful. The federal criminal code doesn’t include such a provision, but its definitions of crimes sometimes require a “willful” violation. This word sometimes requires the “voluntary, intentional violation of a known legal duty,” but courts have said that’s not what it means in contempt cases. Then it’s enough that the accused deliberately refused to comply with a congressional order ultimately found valid. Her mistaken belief that she acted lawfully is no defense.

The federal doctrine that comes closest to giving Meadows a defense is called “entrapment by estoppel.” The Supreme Court first approved this doctrine in 1959 in Raley v. Ohio. When called before the Ohio Un-American Activities Commission, four witnesses invoked the privilege against self-incrimination and declined to answer its questions. The chairperson of the commission assured them their privilege would be respected. But it turned out that the witnesses hadn’t validly claimed the privilege. Although neither they nor the chairperson knew it, a state statute granted witnesses before the commission immunity from prosecution. Invoking the maxim that ignorance of the law is no excuse, a state court convicted the witnesses of contempt for failing to answer the commission’s questions.

The Supreme Court held that the witnesses’ convictions violated the Due Process Clause. To uphold these convictions, the court said, “would be to sanction an indefensible sort of entrapment by the State—convicting a citizen for exercising a privilege which the State had clearly told him was available to him.”

Just as the chairperson of a state commission assured the witnesses in Raley that they could lawfully refuse to answer, OLC opinions assured Mark Meadows that he could lawfully refuse to show up. Nevertheless, if prosecuted, Meadows would have little chance of establishing a defense of entrapment by estoppel, for, unlike the witnesses in Raley, he wasn’t entrapped. The select committee repeatedly rejected his claim of immunity, and, citing the decisions of Judge Bates and Judge Jackson, it informed him that the judicial precedents were all on its side. The Justice Department’s opinions to the contrary couldn’t have led Meadows to believe reasonably that his conduct was lawful; they could at most have led him to believe that the issue remained open. Meadows, in fact, might have known the state of the law as well as anyone else in the world. He deliberately took a chance.

Taking a legal position that a litigant or witness believes reasonably might prevail isn’t culpable. And, although reasonable good faith doesn’t save ordinary mortals from conviction and punishment when they bet wrong, a court might conclude that current and former officers of the executive branch must be allowed to make reasonable claims of executive privilege or testimonial immunity without risking criminal punishment. A court might create a special constitutional good-faith defense for them. This possible defense, however, could prove problematic. It could create a de facto privilege not to testify whenever officials have a reasonable guess they might be privileged.

Meadows probably would have no viable defense if prosecuted, but that doesn’t mean the Justice Department should prosecute him. Prosecuting someone for conduct the department itself proclaimed lawful in published and still unrecanted opinions would be troublesome, especially when one of these precedents was on point and only a few years old. And Meadows wasn’t culpable when he took a legal position that he reasonably believed might prevail. The department could clarify the law by abandoning the precedents that could have misled Meadows and then affording him a second chance.

A decision not to prosecute could give Meadows a reset, not a pass. The select committee could put new return dates on its subpoenas and reissue them the day after the Justice Department announced its decision. When Meadows disobeyed the committee’s initial subpoenas, his claims of executive privilege and testimonial immunity both looked plausible. But neither claim would pass a “reasonable good-faith” test if the Justice Department recanted the only authority that gave credence to Meadows’s immunity claim. Meadows would know that disobeying the new subpoenas would bring certain prosecution, almost certain conviction, and perhaps a tougher sentence than he would have received for his earlier, less culpable disobedience.

Complying with the new subpoenas wouldn’t prevent Meadows from invoking successfully a privilege that sounds less grand than “executive” privilege, the privilege against self-incrimination. But that privilege might not excuse him from producing many damaging documents. Declining to charge Meadows with contempt would remove some of the leverage the Justice Department and the select committee otherwise would have for inducing his cooperation, but the threat of conviction for a misdemeanor looks less and less significant as the department’s and the select committee’s other levers (for example, the prospect of Meadows’s conviction for conspiring to defraud the United States) grow stronger.

Charging Meadows with contempt of Congress would be justified. He appears to have no plausible defense. And not charging Meadows after withdrawing the published opinions that might have misled him would be justified too.

A third possible decision of the Justice Department, however, would be unfortunate. The department’s conflicting interests might resume their customary alignment after the next election, and the department’s top officers surely have that possibility in mind. They know the partisanship of the other party, and they’ve heard threats to subpoena and jail “every single Democrat official surrounding Joe Biden in the White House.” Just as OLC precedents block appropriate (and sometimes vital) congressional investigations, they make it easier for presidential advisers to resist congressional abuse.

For one thing, these precedents enable the Justice Department to keep litigation going for years. Despite Judges Bates’s and Judge Jackson’s forceful rejection of OLC’s rulings in the Meirs and McGahn cases, the Justice Department largely prevailed over Congress. Neither of its appeals led either to reversal or to an affirmance the department would have accepted as authoritative. Rather, both cases ended in settlements requiring limited closed-door testimony by Meirs and McGahn after Presidents Bush and Trump had left office. The earliest of the OLC opinions, written by Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist in 1971, included a statement later administrations might have framed and taken as their motto: “All the Executive has to do is maintain the status quo, and he prevails.”

An overly protective Justice Department might adhere to its precedents and might decline to prosecute Meadows on the basis of its unaltered, unsupported and insupportable view that former close advisers of the president are entitled to defy Congress, however strong Congress’s need for their testimony and however weak their claims of executive privilege might be.