Why I Do Not Hate Donald Trump

Many people would probably believe me justified in hating Donald Trump.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Many people would probably believe me justified in hating Donald Trump.

While I was general counsel of the FBI, I watched the president fire my boss and friend, Jim Comey. I’ve read and heard the many false statements that the president and his supporters have made about him. I’ve also read many of the president’s harsh and erroneous statements about the FBI, the Department of Justice and the people who work at both of those places. The Mueller report describes troubling conduct by the president concerning the Justice Department. I fear the short- and long-term damage such statements and actions will have on those institutions to which I have dedicated most of my professional life; I fear the consequences for the rule of law itself in the United States.

On an even more personal level, I was removed from my job as FBI general counsel after serving under Director Chris Wray for a few months. The president has tweeted and spoken about me personally, uncharitably and by name, on several occasions. Some people who support the president also have said negative things about me publicly. All of that attention impacted me negatively in numerous ways—both personally and professionally—over the past few years.

But I do not and will not respond to Donald Trump with hatred. To the contrary, I have come to believe that the best approach for me regarding President Trump—the only approach—is love. I will try to love him.

I will try to love him as a human being. I will try to love his family. And most importantly, I will try to love his supporters—all of them. Loving Donald Trump and loving his supporters is the best way for me to love America and to honor those who sacrificed so much for my freedom.

I recognize that this view will strike some people as naive, even foolish. I know it may sound weak. But the love I am speaking of is not submission, acquiescence, obedience or deference. Love is strong, it is bold, and it can be defiant. Love resists evil, hatred, bigotry, and all other forces that dehumanize, oppress, victimize or degrade others. Love is the opposite of those values. It is the most powerful resistance to those forces. Loving someone does not mean that you approve of or condone his or her words and deeds.

I admit that loving Donald Trump is a challenge for me. But my journey over the past several years has convinced me that I must try.

Before saying more about that personal journey, I first want to address some of the public criticism of me and of the FBI itself, much of which has come in the context of the FBI’s investigation of Russian efforts to influence the 2016 presidential campaign. I want to make clear that my argument for love in no sense represents an acknowledgment that the investigation is fundamentally defective. Indeed, the various charges brought by Special Counsel Robert Mueller and his report show clearly that it is not.

A lot of the criticism seems to be driven by the notion that the FBI’s investigation was, and is, an effort to undermine or discredit President Trump. That assumption is wrong. The FBI’s investigation must be viewed in the context of the bureau’s decades-long effort to detect, disrupt and defeat the intelligence activities of the governments of the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation that are contrary to the fundamental and long-term interests of the United States. As Benjamin Wittes quoted me saying, the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation regarding the 2016 campaign fundamentally was not about Donald Trump but was about Russia. Full stop. It was always about Russia. It was about what Russia was, and is, doing and planning. Of course, if that investigation revealed that anyone—Russian or American—committed crimes in connection with Russian intelligence activities or unlawfully interfered with the investigation, the FBI has an obligation under the law to investigate such crimes and to seek to bring those responsible to justice. The FBI’s enduring counterintelligence mission is the reason the Russia investigation will, and should, continue—no matter who is fired, pardoned or impeached.

I recognize and accept that some of the public criticisms of the FBI and the Department of Justice are justified. The FBI is not perfect. People make mistakes and use bad judgment. The FBI has a lot of power and therefore needs oversight and must be held accountable. The president’s statements and those of some of his supporters, however, have gone far beyond legitimate criticism.

So why love?

I have known Jim Comey for a long time; my job as FBI general counsel was the third time in my career that I had worked directly for him. Over the years, we’ve had numerous conversations about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—who was famously the subject of FBI surveillance.

As we’ve had these discussions over the years, Jim Comey has repeatedly mentioned Dr. King’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” written in April 1963, during the time the FBI was investigating him. Stupidly, I never bothered to read it until relatively recently. The occasion for my doing so was Jim’s appearance at Brookings last year, where he mentioned the letter as one of his favorite pieces of literature.

This time I read it, and I realized my error in not having done so before. It is a profound and moving reflection on the nature of justice, injustice, law, morality, oppression and the struggle for freedom. I was struck, in particular, by Dr. King’s response to the accusation that his nonviolent direct action campaign was “extremist”:

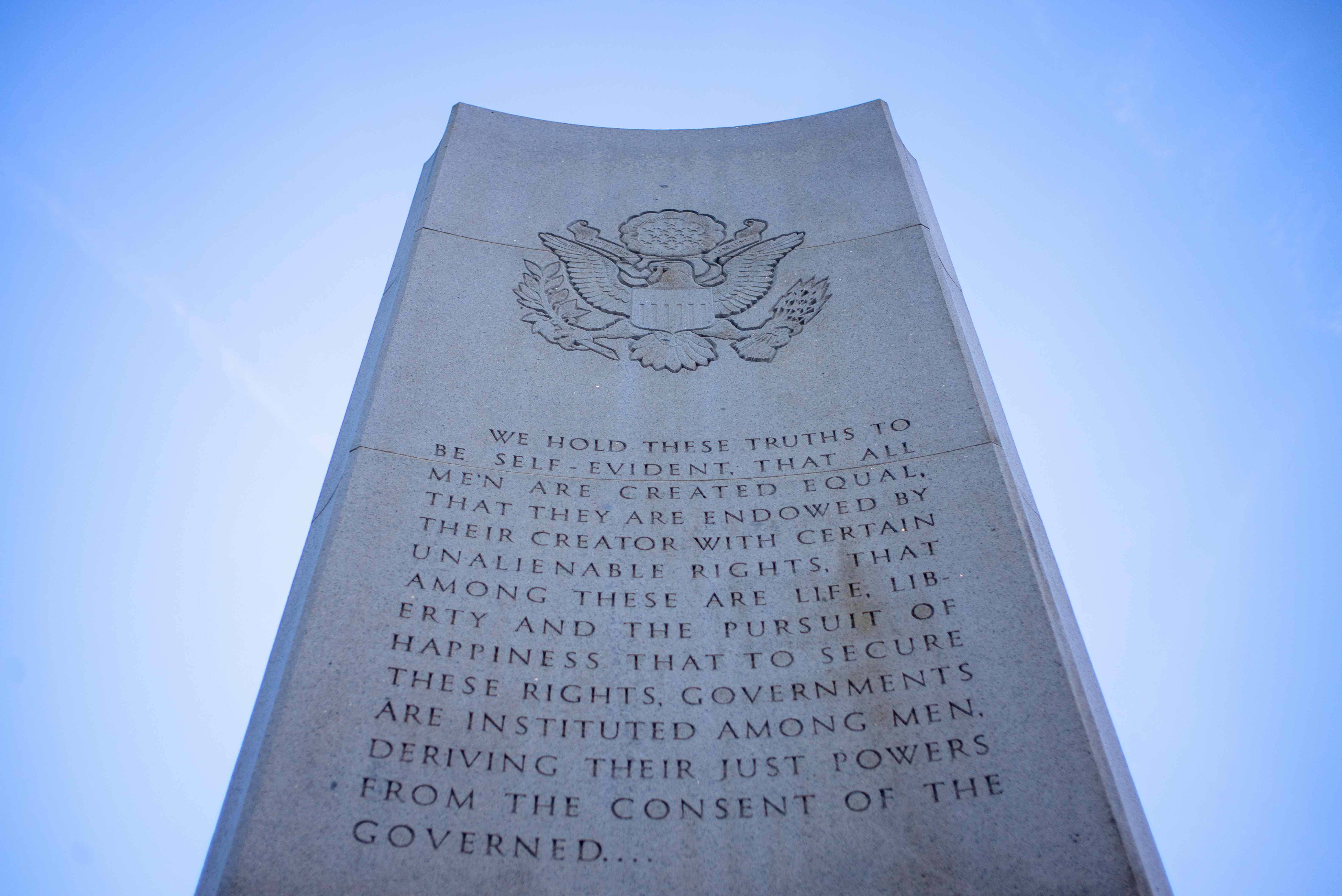

But as I continued to think about the matter, I gradually gained a bit of satisfaction from being considered an extremist. Was not Jesus an extremist in love?—“Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice?—“Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the gospel of Jesus Christ?—“I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist?—“Here I stand; I can do no other so help me God.” Was not John Bunyan an extremist?—“I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a mockery of my conscience.” Was not Abraham Lincoln an extremist?—“This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist?—“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” So the question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate, or will we be extremists for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice, or will we be extremists for the cause of justice? (Emphasis added.)

In a single, effortless paragraph, Dr. King weaves religion, philosophy, political theory and history with contemporary events and uses them to confront the violent response to the civil rights movement and the profound injustice of segregation. As I read it, I wondered what Dr. King might advise us as a nation if he were here today. I am not a King scholar; I am a white man who did not know him. And so I invoke him with real reservation and humility. But, as a person who finds himself tied in some small way to the history both of his time and of our own time, I have read and re-read Dr. King’s quotation of Jesus, found in Matthew 5:44, the full text of which is: “But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” I ask myself how to answer his questions about extremism: Will I be an extremist for love or for hate? If for love, am I even capable of meeting that challenge?

I want to be clear about a few things. First, I am not a pacifist. Indeed, in some of my roles in the government, I have provided advice and assistance in support of the government’s use of lethal force in a variety of contexts. I stand by that work. Second, I am not equating Donald Trump and his supporters with the people about whom Dr. King was writing. The president’s supporters come from many backgrounds, and I am confident that the vast majority support the president for reasons that have nothing to do with racism. As for the president, he has made troubling statements about race, especially regarding Charlottesville. But he is not Bull Connor or one of the other violent segregationists with whom Dr. King and others involved in the civil rights movement dealt. I understand that the picture regarding some of the president’s supporters is more complicated. But it is important not to paint with too broad a brush regarding the Americans who support Donald Trump and thus miss the bigger picture. By referencing Dr. King, I am not calling President Trump and his supporters racists. Finally, by quoting Jesus on this subject, I’m not saying that Donald Trump or his supporters are my enemies.

That said, I, like many others, have struggled to figure out the best way forward for our country today, and people I know and care about seem to be living in alternate universes. I have friends and family members who intensely dislike Donald Trump—hate is not too strong a word—and believe that he is destroying this country. I have friends and family members who voted for him and believe that he is a great president, even if they don’t like everything that he has done or how he has done it. They represent the larger divisions in the nation—where each side derides the other. One of my dearest relatives, who happens to be a supporter of the president, asked me last year, “Jimmy, is everyone at the FBI corrupt?” I was dismayed.

I recognize that I cannot control what other people say or think about the FBI or me. So I offer my response—which is all I can control—and commend it to the president’s opponents in hopes that it might set us on a better path. Politically, the current approach, anger and hatred, isn’t working for President Trump’s opponents: The president’s poll numbers have remained roughly constant over time. Some 90 percent of Republicans apparently support him. Morally, those who view the president as crass, hateful and demeaning do themselves and the country no favors by exhibiting such behavior to any degree in their own words or deeds.

The evidence suggests a new approach is needed. I propose a path of love.

Now, I confess that I do not know exactly what that means—not even for me. I am still trying to figure that out, so I can’t begin to say what it might mean for someone else.

But here are a few things I think about love as the driving force of our civic life. Loving someone with whom you disagree or whom you do not admire holds the potential for transforming that person for the better. But even if it appears to have no effect on the other person, loving transforms and frees the person who loves. It allows one to set down the exhausting weight of hatred, anger and disappointment. It is a proactive act. It means taking control of the situation. The reaction of President Trump and his supporters to love is inconsequential. By loving them—whether they accept, or reject, or mock the sentiment—the president’s opponents can move toward an agenda that they set, hopefully one that seeks to unite and serve all Americans. The Dalai Lama says that “[w]orld peace can only be based on inner peace. If we ask what destroys our inner peace, it’s not weapons and external threats, but our own inner flaws like anger. This is one of the reasons why love and compassion are important, because they strengthen us. This is a source of hope.”

I write all this with significant trepidation. Several people have counseled me against publishing this, saying it is too risky in this unpredictable environment. As a result, I have sat on it for several months after completing it. I also recognize that my situation is very different from that of many others who have suffered under the president much more than I have. I was not at Charlottesville, I am not Muslim and I have not been separated from my children at the border.

But I did hold a high-ranking position at the FBI—an organization that I love—and I have seen colleagues mistreated. And the president of the United States has made negative public comments about both the bureau and me. Notwithstanding all that, I am refusing to choose hate as a response. I am choosing love, even if I don’t fully understand what I mean by that right now. I am choosing that path because I think that is what is best for America.

The path you choose is up to you. But remember that the path we take defines each of us and will impact, to one degree or another, the country we all love.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)