Why Is Vladimir Putin So Difficult to Deter?

Personalist leaders present unique challenges for deterrence.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: When a plan to coerce another state is devised, it’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming the state’s leader is rational, has access to good information, and is responsive when the country as a whole suffers. Rose McDermott of Brown University, however, points out that many states are led by personalistic dictators. They are often willing to allow their countries to undergo hardship, and their foibles and vanities make coercion far harder.

Daniel Byman

***

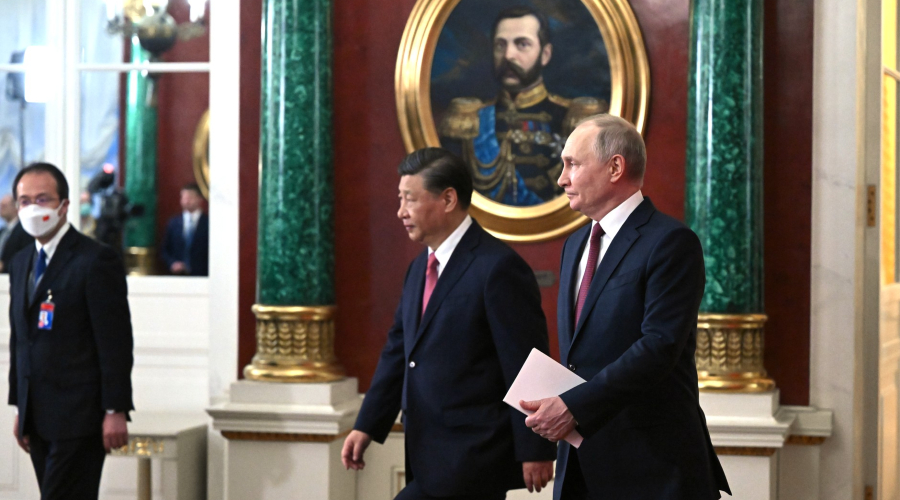

Since he launched his war in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has engaged repeatedly in nuclear saber rattling, announcing most recently that he would deploy nuclear weapons to Belarus. The question remains: Would he ever use such weapons to further his political and military aims? Some observers claim he is rational and can be deterred by threats of massive retaliation, while others argue that he might use nuclear weapons for more impulsive and personal reasons, such as if his forces continue to lose on the battlefield and he feels backed into a corner, and especially if he feels his personal legacy is at stake.

In a chapter I wrote recently for the book “The Fragile Balance of Terror," I examine three important ways in which personalist leaders like Putin pose threats to the stability of nuclear deterrence. First, they operate under fewer organizational and institutional constraints—such as courts, parliaments, or legislatures—than democratic leaders, while privileging loyalty over competence in their advisers. They privilege loyalty because they often remain more concerned about an internal coup than an external strike. This allows corruption to run rampant and limits the availability of expertise. It also inclines such leaders toward paranoia because they have to remain constantly vigilant against threats of overthrow that often are synonymous with assassination. Second, their ability to maneuver without much restraint gives free rein to idiosyncratic personality dynamics, especially narcissism. One of the many problems with narcissistic self-focus is that it privileges what the leader thinks is best for him without regard to the costs and consequences of the larger body politic. For example, the campaign of throwing men into the battle in Ukraine may be what Putin thinks is best for winning that fight but does not consider the huge personal waste of lives such a strategy entails. Last, such leaders tend not to learn well from their own mistakes or those of others, not least because they surround themselves with sycophants who always validate their views, giving them a distorted sense of their own skills, abilities, and knowledge. In combination, these factors render personalist leaders easier to provoke and more prone to react to threats with aggression, making the world a less stable and more dangerous place.

The tactics and strategies that the United States and other democracies have depended on for the past half century to secure nuclear deterrence may not work as well against such personalist leaders. The traditional U.S. approach to deterring regimes from nuclear use typically involves diplomatic negotiations to deter unwanted actions and escalations, and emphasis on the risk of retaliation; when a nuclear-armed state invades another country, engages in nuclear proliferation, or otherwise violates meaningful international norms of behavior, the United States has also imposed economic sanctions as a penalty. These actions may constrain leaders who are well informed and accountable to their regime supporters or public but may be less effective with personalist leaders.

Because personalist leaders are less constrained by domestic institutions or constituencies, they are more insulated than their democratic counterparts from consequences that punish their populations such as economic sanctions. The current economic sanctions imposed on Russia as a result of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine provide a good example: While Western audiences are told that the sanctions are working gradually, they do not seem to have imposed any undue hardship on Putin’s lifestyle, noticeably restrained his war effort, changed his war aims, or brought him to the negotiating table. The national sanctions are not compelling change because Putin does not face pressure from the ordinary Russians affected by them. The general public poses no meaningful check on his behavior because he is able to use coercive force, such as arrests, to prevent mass protests and control the media so that few, if any, dissenting voices can express opposition to the war openly. Other sanctions target Putin’s closest supporters and cronies in the hope that these individuals will pressure Putin to change his tactics and perhaps even end the conflict. So far, these more targeted sanctions do not appear to be any more effective at changing Putin’s goals and strategies than the broader ones. This is at least partly because Putin does not seem to heed advice from the individuals targeted by more specific sanctions, if indeed they try to persuade him.

Similarly, diplomacy and negotiations have not been able to force Putin or other personalist leaders to accept U.S. objectives or adhere to international norms, in part because they do not need to heed any public or elite constituencies who might oppose nuclear opposition. For example, seemingly endless efforts at negotiation have utterly failed to prevent North Korea’s Kim Jong Un from increasing his proliferation of nuclear weapons. Hostile or threatening rhetoric has not achieved a positive result either—Donald Trump’s threat to rain “fire and fury” on Kim did not dissuade him from continuing his acquisition and testing of nuclear weapons. Leaders concerned about the potential for U.S. military intervention may acquire nuclear weapons because they believe it can deter an invasion and the ouster of their regime. For leaders such as Kim, acquiring nuclear weapons and threatening their use may seem rational, and they have few constraints to stop them from implementing their personal preferences in state action. A broader elite within a democracy might support the acquisition of nuclear weapons, such as in India, but a larger constituency would also allow for a wider debate regarding the value of such weapons, including a consideration of those voices that might oppose such weapons because of the pressure the United States and its allies might exert.

A different approach with such leaders is more likely to bear fruit, perhaps even at lesser financial cost, than the existing predominant strategies. Sometimes personalist leaders want material things, like territory, that the United States and its allies may not be willing to cede. However, in many cases, they are driven by narcissism or paranoia, and what they seek is status on the international stage. Personalist leaders are more likely to fight for status and personal security than for material resources, and are certainly more likely to take greater risks to preserve previously attained status. One of the ways such leaders may try to obtain status in the international environment is through the acquisition or threat of use of nuclear weapons. Such weapons serve as a powerful signal of potency in international relations, especially for states that might not otherwise receive the attention they feel they deserve because they have limited economic or cultural influence. North Korea is a perfect example of a state that could never claim major-power status on the basis of its economy but demands such recognition because of its possession of nuclear weapons alone. Thus, nuclear weapons serve as a symbol of status that short-circuits the need for widespread economic development or other social or cultural achievements. Personalist leaders may not actually want the coercive force provided by nuclear weapons so much as they want the status such weapons convey. Recognition of that status can deescalate hostilities and produce positive returns. Think about Nixon going to China—in addition to working with Beijing to balance Soviet power, Nixon’s willingness to travel and display respect opened the door for improved relations and enhanced trade with China.

Looking at deterrence from the perspective of personalist leaders shows that attention to status and safety may prove more profitable than a focus on material factors. Threats are likely to simply force such leaders to double down, knowing that their only route to personal safety is through victory. At the same time, open acknowledgement of status, and even flattery, may achieve goals that material factors cannot achieve. For example, Dennis Rodman, who at the time claimed he did not know the difference between North and South Korea, began visiting Kim Jong Un starting in 2013; Kim was apparently a diehard fan of the 1990s Chicago Bulls, for whom Rodman played. In this capacity, Rodman even brokered the release of an American hostage.

In addition, assurances of personal security may go further than with other regimes, especially since personalist leaders may be as afraid of their followers as they are of external adversaries. The promise of a safe exit has been used as a bargaining chip frequently in negotiations with long-standing African leaders. For example, Mengistu Haile Mariam, who ruled Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991, received sanctuary in Zimbabwe after he was removed from power. And in 2014, Burkina Faso’s leader, Blaise Compaoré, sought refuge in the Ivory Coast in a deal that was brokered by France. Offering a safe haven if they agree to leave power may solve multiple problems for all the parties involved. In this way, the International Criminal Court’s recent indictment of Putin for war crimes, no matter how morally justified, may work against the goal of removing him from power peacefully.

Appreciating the role of social approval and recognition of high status in personalist leaders’ behavior provides important avenues for the amelioration of conflict—but in practice such policies may be difficult to enact. Indeed, the loss of higher status seems to be part of what drives Putin; he is motivated not simply to re-create the strength of the former Soviet Union, but personally, and more significantly, to attain the prior glory of Peter the Great. The recognition of the personalist leaders’ status desires should lead democracies to avoid destructive and costly strategies, such as the imposition of economic sanctions, the restriction of energy imports, or the actual conduct of war, while simultaneously encouraging novel strategies for negotiation or subversion.

Of course, sanctions can serve other purposes, such as signaling disapproval, and these goals may be valuable for manipulating status perceptions; however, Western leaders should remain aware that there are limits to how much can be achieved using such coercive tactics against personalist leaders. Such strategies may be useful for domestic audiences or when trying to pressure other democracies but will be much less effective when used against leaders who do not have to be as responsive to their constituencies. Other status-based strategies might be more persuasive with personalist leaders. One can imagine, for example, that inviting Kim Jong Un to a fancy White House dinner might produce greater results than years of negotiation. However, the strong reaction that this kind of move would provoke domestically shows how attentive all actors are to public displays of status. In addition, such recognition would probably not sit well with U.S. allies who feel threatened by North Korea, such as Japan and South Korea, because they may feel that such a show of respect indicates a weakening of support for them. Opposition to such deference also demonstrates just how difficult it may be for strong states to seemingly render equal status to ostensible weaker ones, even if such a move might bring about a desired result. It is easy to see why such strategies are challenging to consider, and many leaders may feel that mere recognition of others’ power may not be worth its domestic cost.

Personalist leaders are particularly challenging adversaries. Their political circumstances make them less accountable to their public and other domestic elites and more inclined to narcissism and paranoia. As a result, they are easier to antagonize and more difficult to deter. Trying to see things from their perspective opens up the possibility for novel forms of deterrence that rely more on psychology, and less on economics or violence, to manage their potentially erratic behavior. These creative approaches would also recognize the greater risk for conflict and escalation these leaders pose—awareness of which should shape the diplomacy of more democratic states.

-(1).png?sfvrsn=fc10bb5f_5)