Why We Continue to Misunderstand Conflict Economies

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

It’s said that the definition of madness is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different outcome. Yet, once again, the international community is using the reports of a government in Kabul to build an understanding of the Afghan economy and the tax revenues that the de facto authorities earn. Corruption shaped the economic political fabric of the Afghan Republic and impacted the very data used to measure and analyze the performance of the economy. This all points to the need for a more skeptical view of the official data reported by Kabul, and other administrations in fragile and conflict-affected states. There is, after all, much that takes place on the peripheries of these states that is difficult to monitor and control; it is part of what defines them.

For example, in February the World Bank reported that the value of cross-border trade between Afghanistan and its neighbors had returned to the levels occurring under the Republic, and that the revenues it generated for the Taliban had increased. Surely, this was a claim that should have immediately set alarm bells ringing given the scale of the current economic crisis in Afghanistan reported by the United Nations and the history of misreporting and false statistics that emanated from Kabul for almost two decades.

After all, Khalid Payenda, the former minister of finance, referred to the scale of corruption at the customs offices as “mind boggling” during the final months of the Afghan Republic and provided a rich account of the scale of the graft occurring at several official border crossings in September 2021. My own research with the United States Agency for International Development as well as our imagery collection at the borders of Torkham, Islam Qala, Abu Nasr Farahi, Ziranj, and Spin Boldak in late 2020 indicated that underreporting at these borders was endemic and that, in most cases, the volume of goods entering and exiting Afghanistan was often more than twice as much as reported.

Take fuel as an example. In contrast to the 1 million metric tons of fuel that the Afghan Republic reported entering the country from Iran in 2019, our report estimated that a further 1.5 million metric tons of diesel specifically crossed the border illegally, much of it through the remote crossing at Abu Nasr Farahi, in the remote deserts of Farah far from the prying eyes of the donors in Kabul. The losses in tax revenue to the Republic from this undeclared trade were dramatic: an estimated $100 million on the diesel trade with Iran alone.

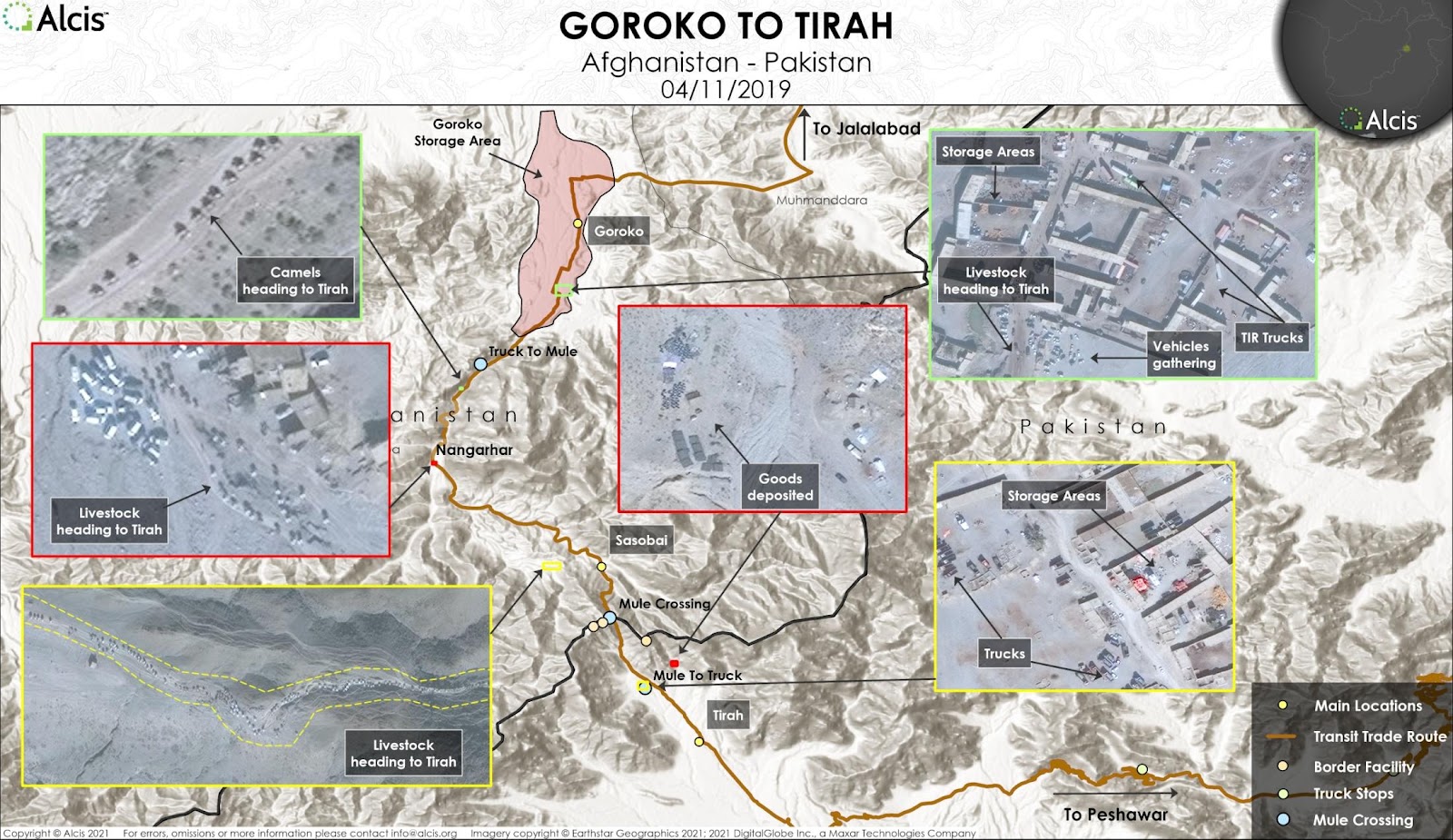

Using high-resolution imagery and in-depth fieldwork, we could see the same problems with the Republic’s official statistics for the import of many transit goods and the exports of coal, talc stone, and chromite to Pakistan. Payenda subscribed to these findings in discussions we had with him and his senior team and the Ministry of Finance only a month before he left the country in June 2021. In several locations on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border there was a vibrant trade in smuggled goods, including cigarettes, car tires, food items, electronic goods, and even cars—a trade that was worth hundreds of millions of dollars per year, all of it occurring in plain sight of the authorities on both sides of the border (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Dismantled cars in Sasobai, Nangarhar, prepared for transport by camel across the border into Pakistan, where they will be reassembled and sold.

Figure 2: Map showing the route from Goroko in Nangarhar to Tirah in Pakistan via Sasobai. Imagery inserts show storage areas and the pack animals laden with goods.

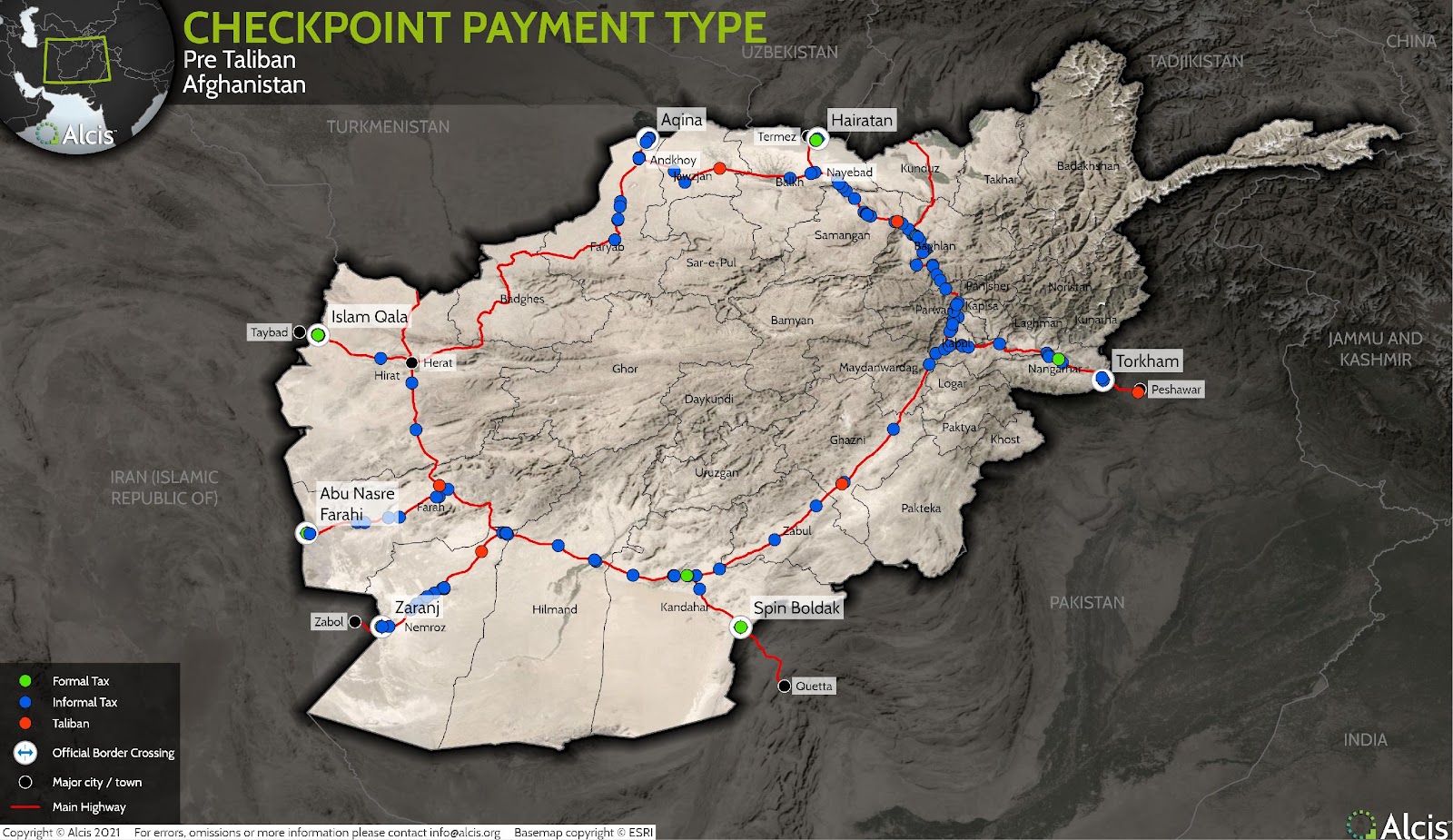

This and my subsequent work with Alcis, a geographic information services company based in the United Kingdom, also showed how this undeclared economy, with large volumes of goods plying the roads with falsified documents, served as a significant source of revenue for corrupt officials on the main highway and their patrons in government, as well as for the Taliban, who earned an estimated $245 million per annum taxing these vehicles. (These checkpoints, prior to the Taliban takeover, can be seen in Figure 3.) As such, corruption was not simply a matter of patronage influencing who won a contract for supplying goods and services to the Afghan government, the tender for mining concessions, or the security for supplies to the international military forces. Rather, it shaped the political fabric of the Republic and distorted the very data by which donors assessed the Afghan government’s economic performance.

Figure 3: Map showing checkpoint of Republic, Taliban, and corrupt officials prior to the Taliban takeover.

Whereas the incentives under the Republic were to underreport revenues and press donors for more funds, the Taliban’s interests potentially lie with aggrandizement and exaggerating the amounts they collect in taxes, to present their administration as financially sound and free of corruption. It certainly seems particularly disingenuous that, given the gaps in the past administration’s official data, comparisons are made with the current de facto authorities in Kabul. For example, comparisons on volumes and values of cross-border trade would seem rather meaningless given the scale of underreporting under the Republic and the unreliability of the data that was produced.

And how are we to judge the veracity of the Taliban’s reports and claims? Certainly, there is some truth to their claim that corruption has been curtailed, particularly when it comes to clamping down at the official border crossings, where drivers, traders, and officials all report strict enforcement of procedures, including an accurate description of goods and their value, the weighing of trucks, and the immediate banking of duties and taxes owed.

But in the face of the economic crisis and what would appear to be a significant downturn in the volumes of trade at several official crossings, especially those with Iran (as seen in Figure 4), would stemming the scale of underreporting by the Republic be enough to increase the amounts collected in duties by the Taliban? And where does the smuggling economy fit in? On what budget line are the taxes collected on goods such as opium and its derivatives, previously deemed illegal under the Republic, entered on the national accounts?

100a3a38-0fbe-4dd5-b1bf-e98aee22f61e.jpeg?sfvrsn=ad02d1cf_3)

The scale of misreporting on official trade in Afghanistan, and the omissions of large volumes of smuggled goods, also suggests that there is an urgent need to deploy more robust methods of data collection if we are to better understand the economies of fragile states and the political interests that underpin them.

We live in a world of innovation and technological advance, where high-resolution satellite imagery can differentiate between a truck carrying a container and another hauling a tanker of fuel, where the volume of grain stored can be measured, and where the truth of claims of impenetrable fences running the length of a country’s borders can be established. While such technologies are not a universal panacea and are best used in tandem with in-depth fieldwork and other sources of data, they do offer a more robust method for checking what is reported in the ledgers of the Ministry of Finance in capitals such as Kabul. The technology is there, and is improving at a rapid pace, but it is for donors and international institutions like the World Bank to embrace these advancements and integrate them into their work practices if they are to better understand the political economy of conflict-affected states like Afghanistan.

This work was supported by the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research program, funded by aid from the U.K. government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the U.K. government’s official policies.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5a43131e_9)