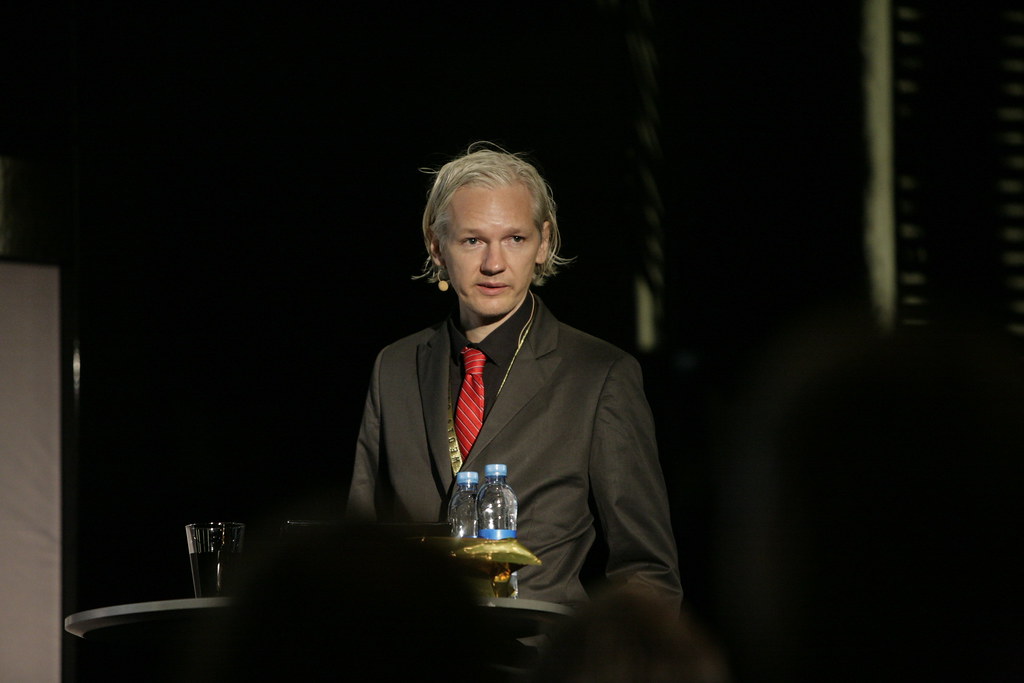

The WikiLeaks Case Is Just Beginning

Julian Assange had to be the worst houseguest an embassy ever encountered.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Julian Assange had to be the worst houseguest an embassy ever encountered. Between Assange’s reportedly hacking the Ecuadorian embassy’s network, creating diplomatic incidents with intemperate tweets, and apparently troubling embassy staff with notoriously poor hygiene, it seems that the Ecuadorian government finally had enough. On April 11, Ecuador called the British authorities to remove the squatter. The U.S. immediately unsealed an indictment and announced an attempt to extradite Assange to the U.S.

It may be years before Assange sees the inside of a U.S. courtroom. The initial Swedish request to extradite Assange from the U.K. came in November 2010. Assange successfully slowed the process until June 2012, when he simply skipped bail and fled to the Ecuadorian embassy. Now, an effort to extradite him to the U.S. on computer-related charges further complicates things.

Two particular cases show the difficulty. In 2013, the U.S. government indicted British citizen Lauri Love for compromising U.S. government computers. It took three years for the court to hear the extradition case, and when it did, Love presented an argument that a long sentence of imprisonment in the United States, combined with his Asperger’s syndrome, would significantly harm him. Two years later, he won on appeal after the court ruled that U.S. prison would be “oppressive to his physical and mental condition.”

There was also Gary McKinnon, who similarly hacked U.S. government systems. After he was indicted in 2002, the extradition proceedings dragged for a decade. Eventually, then-Home Secretary Theresa May withdrew the extradition order because of McKinnon’s diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome and depression: “Mr McKinnon's extradition would give rise to such a high risk of him ending his life that a decision to extradite would be incompatible with Mr McKinnon's human rights.”

Assange’s appeal against extradition may prove to be a replay of the Love and McKinnon cases, on an even larger scale. As with Love and McKinnon, Assange’s appeal will likely be directed as much at the British public as the courts. The Love and McKinnon cases suggest that both the U.K.’s public and its courts may be swayed by arguments pointing to the defendant’s mental state, the conditions of U.S. prisons, and the technically very high (if often misrepresented) statutory maximum sentence the defendant might face. Threats that imprisonment in the U.S. may lead to suicide are especially powerful, and McKinnon gained significant support over concerns he might end up at Guantanamo Bay. In Assange’s case, further increasing the difficulty of extradition may be public statements by U.S. officials. Every call to be “harsh” on Assange is going to strengthen his case within the U.K.’s court of public opinion.

The WikiLeaks saga is far from over. Julian Assange may be in British custody for a long time as this plays out.