Will China Retaliate Against U.S. Chip Sanctions?

Expect an asymmetric response; direct actions would wreak havoc on both China and the global economy.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Semiconductors, the core of the digital economy, are now a central point of geopolitical contention. Semiconductors, or chips, are the thumbnail-size devices that enable every electronic application on the planet—from cell phones and automobiles to aircraft and satellites. Both the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) view the industry as critical to economic growth, global competitiveness and national security. Recent automobile manufacturing shutdowns, driven by a shortage in the availability of semiconductors, have pushed the industry into the headlines and under a microscope.

Over the past few years, the United States has slowly tightened restrictions around key semiconductor players in China. Beijing, however, has largely held its nose, content to pour billions into building its own chip ecosystem while refraining from lashing out at foreign firms. Many analysts presumed that trade tensions pervading the semiconductor industry would improve with a change in U.S. administrations. This has proved to be unfounded. If anything, there is a stronger bipartisan consensus now on the dangers from an ascendant China than at any point since Richard Nixon reopened the relationship between the two countries in 1972. Indeed, the Biden administration just doubled down on the Trump strategy with an expansion of the Entity List, preventing U.S. companies from doing business with companies on the list without government approval. The U.S. and China are likely to continue the current path unless something triggers Beijing’s leadership to modify its approach to human rights, its increasingly aggressive military buildup and hegemonic goals, and its abrogation of trade practice obligations taken under the World Trade Organization (WTO).

U.S. Sanctions

In response to a barrage of Chinese trade infractions (intellectual property theft, forced technology transfers, cyber espionage and WTO violations), the U.S. government implemented a sanctions regime that has inflicted increasing pain on China's semiconductor industry and the future competitiveness of its commercial and defense customers. These restrictions include tariffs, increasingly restrictive approvals of mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures and export licenses for advanced technologies, the expansion of the Denied Persons List, and the enactment of the Foreign-Produced Direct Product Rule. These actions have debilitated Huawei's access to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC’s) leading-edge technologies, truncated the technology road map of China’s leading logic foundry Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation by the denial of access to the Dutch equipment firm ASML’s latest photolithography tooling (extreme ultraviolet, or EUV), and cut off support of chip design tools to a host of leading-edge Chinese chip designers.

To date, China has retaliated with tariffs and chip import restrictions, saber-rattled with respect to Taiwan, and passed legislation that nominally allows extraterritorial jurisdiction against entities that pose a threat to China's national security. But otherwise, China has kept its powder dry. In response to the U.S.’s recent moves, what additional levers does China have? How can China pressure companies in the global semiconductor industry? The U.S. sanctions sword is double-edged and cuts both ways.

China’s Levers

China can choose targets of retaliation in a direct or asymmetric manner. Given China’s relatively weak position across the semiconductor supply chain and its high dependence on chips for national security and economic growth, it will likely opt for an asymmetric approach. Direct retaliation against the chip industry would likely trigger a self-inflicted wound, and some of China’s levers lack sufficient precision to target individual firms or countries. But semiconductor leaders and global policymakers dismiss the potential disruption of a direct approach at their own risk. Prior to exploring China’s calculus, it would be useful to assess the several potent levers on the other edge of U.S. sanctions.

Squeezing Global Supply Chains via Global OSAT Share

While China has struggled to catch the leaders in advanced semiconductor production, it has quietly cemented global share leadership in the outsource package, assembly and test (OSAT) market.

In one key step in semiconductor manufacturing, silicon die from wafers must be packaged and tested prior to being used in upstream applications—a process known as OSAT. Boston Consulting Group recently reported that China has a commanding 38 percent share of value-add in this market. While much of this share supplies Chinese customers, roughly 15 percent of global OSAT value-add is performed in China for non-Chinese consumption. The three largest firms include Jiangsu Changjiang Electronics Technology (which acquired Singapore leader STATS ChipPAC in 2014), TongFu Microelectronics and Tianshui Huatian Technology. In addition, several global memory and logic manufacturers have package, assembly and test operations in China. The PRC could wreak havoc on global chip supply chains with directives to China-based operations of these firms to deny or restrict capacity allocation or supply their inventory to select companies or regions of the world. Such a move would be self-defeating as OSAT is a relatively low-skill and scalable sector of the market, and Chinese OSATs need close cooperation with foreign foundries (semiconductor companies that manufactures parts designed by other companies) and integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) (semiconductor companies that design and manufacture their own parts) to upgrade and improve their profit margins. Global firms would certainly face short-to-medium-term disruption and would likely revise sourcing plans to use non-Chinese suppliers. China’s OSAT ecosystem would be negatively affected over the long term.

Frustrating Industry Merger and Acquisition Deals

China can and has interfered with U.S. corporate mergers and acquisitions and consolidation strategies, as in the 2018 Qualcomm/NXP deal and most recently with Applied Materials' proposed acquisition of Japan's Kokusai in the equipment sector. As most semiconductor multinationals have business operations in China, mainland regulators can block deals or alternately extract concessions. Two impending moves in the semiconductor industry include AMD’s proposed acquisition of Xilinx and Nvidia’s bid for ARM. Chinese companies have extensively deployed ARM processors across a range of applications, and Chinese regulators will be looking for assurances of continued access to the technology. Mergers and acquisitions enable companies to accelerate entry into new markets, access technology, and improve prospects for growth and financial performance. Blocking these deals is a not-so-subtle way for China to frustrate U.S. companies and pay back similar U.S. actions. After all, the U.S. taught China how to play this game, notably with a Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States denial of China’s acquisition of German equipment maker Aixtron by the Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund; Canyon Bridge's acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor, which would have accelerated China's access to field-programmable gate array technology (a specialty chip with software functionality that can be programmed after being shipped) and its application to a wide array of national security platforms; and most recently by nixing China’s Wise Road Capital attempted acquisition of Magnachip, a Korean 200mm foundry.

Rationing Rare Earth and Critical Materials Where China Retains Commanding Market Positions

Today's headlines about semiconductor manufacturing focus on announcements by Samsung, TSMC and SK Hynix, along with Intel's IDM 2.0 resurgence strategy. These $100+ billion expansion plans, however, rest on a vulnerable foundation of obscure compounds dominated by Chinese producers. To make chips, all semiconductor fabrication plants (commonly known as fabs) need a host of high-purity gases, photoresists and specialty chemicals from companies in Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and Germany, which in turn depend on China for a supply of rare earth materials for their production. Boston Consulting Group highlights that of these 17 rare earths, China leads in the extraction of nine and in the refining of 14. The technology advisory services firm TECHCET reports that China controls an 82 percent share of rare earth materials or critical minerals, including 80 percent of global tungsten supply. Rare earths can be mined in many countries, but China controls the refinement and purification processes, and indirectly controls supply, pricing and export control. While China perhaps does not have a stranglehold, its position in this sector conveys considerable leverage. Denial of access or rationing the supply of critical rare earths to targeted Chinese supply chains, while perhaps a blunt force approach, could quickly grind global chip production to a halt.

Denying Access to China's Market

Global semiconductor multinationals have been beating a path to China's market door for the past two decades. The motivations of gaining access to subsidized, low-cost and highly scalable manufacturing operations have been clear. But equally important is proximity to Chinese customers and access to China's market. Boston Consulting Group reports that China's end-use consumption of chips is 24 percent of global sales, roughly equivalent to that of the U.S., and that 35 percent of global semiconductor revenue is produced or assembled in China. While China has only 16 percent of global chip manufacturing capacity today, it remains one of the fastest growing markets for equipment players. Applied Materials' 2021 second-quarter results offer a poignant example: China constituted a full one-third of its sales for the quarter and represented a 62 percent increase year-over-year. While China has limited options in many equipment segments, that buying power, or its denial, represents leverage over U.S.-based companies. Where alternatives exist, China is flexing its muscle. Take the example of smartphone application processors. Taiwan’s MediaTek became the top global smartphone system-on-chip supplier of 2020 with a 48 percent year-over-year increase and 10 percent market share gain, mostly at the expense of U.S.-based Qualcomm. These gains were largely due to a coordinated replacement strategy by high-volume Chinese smartphone makers Oppo, Vivo, Xiaomi and Huawei in response to U.S. sanctions and tariffs. Future access to China's market remains critical to the scale, research and development competitiveness, and financial returns of virtually all players in the semiconductor value chain.

Taiwan

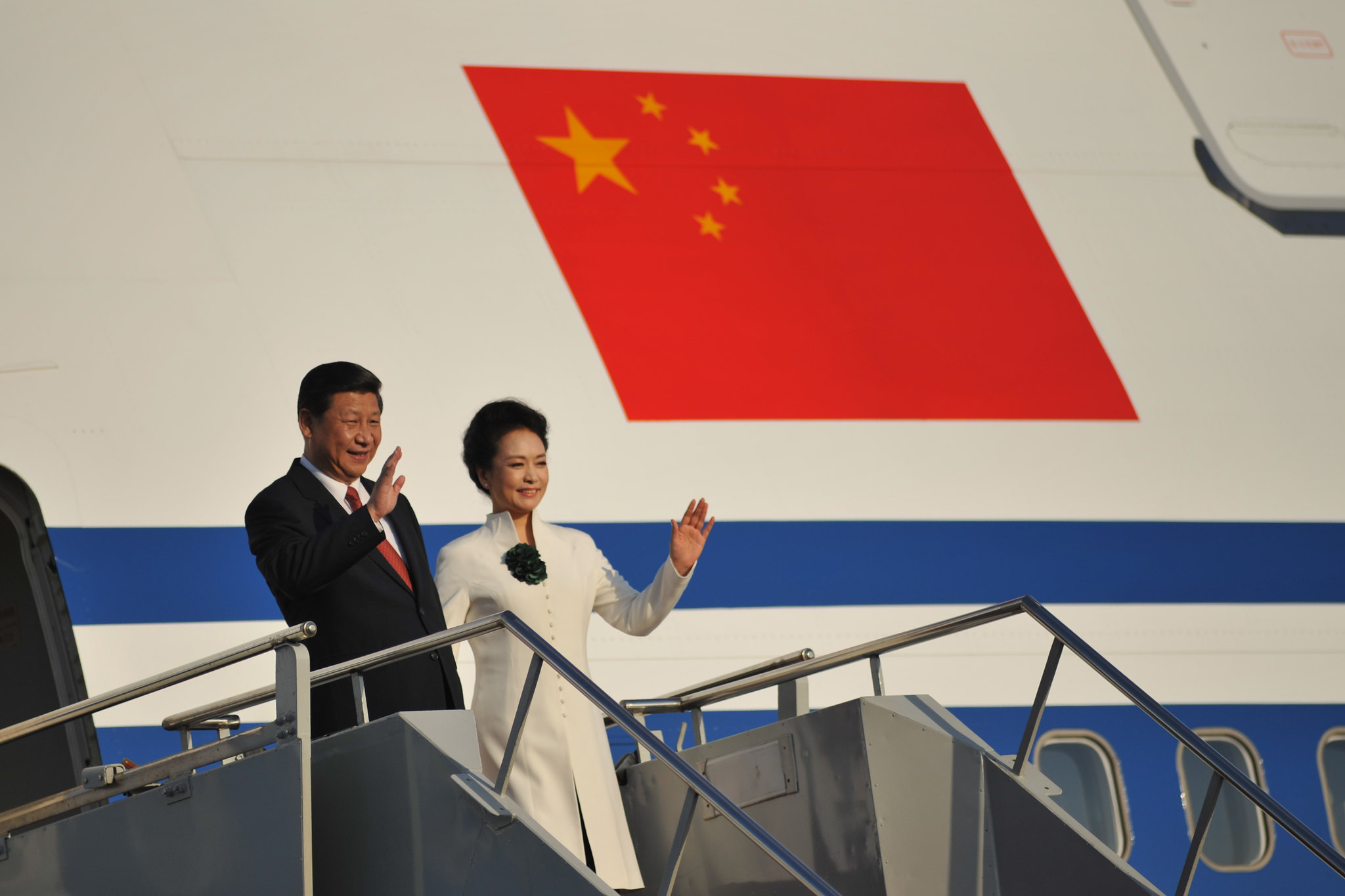

The media is replete with assertions of a pending Chinese takeover of Taiwan. Beijing views Taiwan as a renegade province and a threat to the primacy of the Chinese Communist Party and the PRC. It seeks "unification" as part of President Xi Jinping’s broader goal of "national rejuvenation" by 2049, the 100-year anniversary of the PRC. The only apparent uncertainty from the mainland is not whether, but how and when, this objective is met. From the perspective of the semiconductor industry and the global economy, such a scenario is unthinkable. Even a nondestructive Chinese takeover of Taiwan would be extremely disruptive. To sustain segment viability, the Chinese government would be fully dependent on existing TSMC leadership and personnel to keep the fabs running; that expertise does not exist on the mainland. Whether China would get the cooperation of Taiwanese employees is an open question. The risk of sabotage to Taiwan's power and water supplies could also threaten continued operation. Beyond that, world powers are almost certain to apply blockade-level sanctions in such an event, inhibiting TSMC's access to needed equipment, spare parts, materials, software and support.

Such a scenario would threaten the sustenance and growth of the global digital economy. It would make the current "crisis" in chip shortages look like child's play. The impact of the chip shortage on the auto sector has been estimated at $110 billion in the U.S. in 2021 alone. The global impact of a sustained supply disruption of chips from Taiwan would move quickly beyond economic impact, triggering national security concerns by every major power. Even more limited moves, such as nationalizing some Taiwanese firms’ mainland facilities, would likely induce significant disruptions. From the point of view of the U.S. and its allies, Taiwan’s chip industry is so critical to global supply chains that it is characterized as Taiwan’s "silicon shield."

Would China Do It?

Over the course of the trade war with the U.S., the Chinese government has been surprisingly reluctant to escalate economically on Western firms. In the past few years, Beijing has certainly heightened border disputes and its diplomatic rhetoric. However, aside from matching Trump’s tariffs during the height of the trade war, the Chinese government has largely kept its powder dry. Take, for instance, the recent controversy over Xinjiang cotton. Initially, Chinese state media escalated grassroots criticism of Western apparel brands for criticizing forced labor. But aside from some frivolous safety screenings of apparel imports, Western states haven’t taken actions against Chinese firms. Similarly, while domestic anti-monopoly actions have dramatically affected the prospects of firms like Ant Financial and Meituan, companies like Apple, which faces anti-monopoly challenges in the West, have largely been left unscathed.

Why has the Chinese government not taken some of the aggressive measures outlined above in retaliation for the United States’ actions on Huawei and ZTE? Fundamentally, China still needs foreign investment and, more importantly, foreign technology. Both investment and foreign technology are necessary for China to upgrade its domestic industry and talent base. China has no qualms about blocking foreign companies from operating in China when domestic firms are at the precipice of challenging Western firms technologically. All foreign companies currently operating or selling into the PRC have already passed a cost-benefit analysis of Beijing believing that it’s better for China’s long-run economic and technological progress if the firm operates. Given the importance that CCP leadership has put on self-reliance, economic bureaucrats believe that chip firms currently doing business in China are, for the time being, more useful than not to keep around.

What would cause Beijing to dramatically change its calculus? Perhaps the U.S. could first escalate by targeting more Chinese firms for the Huawei “nuclear option,” or the U.S. could convince other countries to squeeze Chinese firms to the point that China feels it has less to lose by dissuading future foreign investment.

The Chinese government will most likely pick its spots and use a few limited examples to send a message. A rising Chinese firm might persuade the government to make an example of its foreign competitor. For example, China could target Apple or Ericsson, two companies for which China has comparable replacements. These replacements would fill up market share without too much deadweight loss on Chinese consumers and firms. In Apple’s case, hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers would be peeved that one of the brands they interact with the most could no longer sell new phones. While Uber was able to mobilize its support among a large consumer base when lobbying New York City’s mayor to change regulations negatively impacting their industry, any strategy along these lines by a Western firm in China would surely backfire. So perhaps business-to-business firms with significant market share are the most likely victims of asymmetric Chinese chip aggression.

The Chinese government might also conclude (incorrectly) that locking one firm out of the Chinese market would incentivize all the others to lobby even harder to keep relations open. But even a smaller-scale move has risks. Any policy along these lines will continue to incentivize firms and companies to think more seriously about diversifying away from reliance on Chinese firms, minerals and markets.

Risk Mitigation

The prudent course in a period of uncertainty is risk mitigation. This applies to countries and companies alike. What course of action should the U.S. and allied countries be taking at this point? How can global multinationals navigate out of the crosshairs of geopolitics and sustain growth and value-creation?

The U.S. and its allies must pursue strategies that rebalance geographic sources of supply away from today's overconcentration in Asia. This is the type of industrial policy envisioned in the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act (still pending the appropriation of funding). The U.S. government should focus on seeding capacity investments not only in leading-edge fabs but also in emerging chip technologies such as gallium nitride and silicon carbide, as well as in segments such as advanced packaging-assembly-test, rare earth mining and refinement, and critical materials. The incentives should enable capacity investments of sufficient scale to meet national security and critical infrastructure needs, but they should not attempt to target 100 percent of domestic demand.

At an operational level, global semiconductor firms should adjust inventory policy to provision higher buffers throughout the supply chain on critical consumable materials (specialty gases, chemicals, raw wafers) that are subject to supply disruption. Strategically, they must define creative approaches to optimize shareholder value in this environment. Companies must comply with host government policies relating to the licensing of technology and shipment of products to China and honor multilateral export controls regimes such as the Wassenaar Arrangement and country-unique entity lists. If these regimes evolve further into an effective "decoupling" between China and the U.S. and its allies, companies face potentially severe economic and shareholder value impact. Boston Consulting Group highlighted the potential loss of 37 percent in revenues and an 18-point loss in market share for U.S. firms in a 100 percent decoupling scenario.

Firms have options. They can exit nonstrategic investments in China to avoid entanglement, migrate asset-lite missions to alternate countries to minimize footprints in both China and the U.S., and modify future capacity plans. They can create alternate "routes-to-China's-market" for technology and products by forming joint ventures or licensing agreements with partners in "neutral" third countries that have fewer restrictions and more degrees of freedom to do business with China. As in the case with electronic design automation companies, which face an increasingly threatening set of competitors in China, firms can form joint ventures in-country and localize (and monetize) their platforms before indigenous firms gain share. They can "invert," changing their country of incorporation through mergers with a foreign entity, to escape the reach of U.S. regulators. That said, these strategies must survive oversight of the U.S. Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act and its foreign counterparts; each carries economic and political risk.

The semiconductor industry yearns to regain its model of open markets, free trade, intellectual property protection, full leverage of geographic competencies, innovation by a multicultural workforce, global collaboration in research and standards, and funding by global capital markets. From the industry's perspective, the case for deescalation is clear. While it would be heartening to see the U.S. and China walk back from the precipice and call a truce on chips and other bilateral flashpoints, the current reality is likely to be with us for some time. In the interim, global semiconductor firms should develop risk mitigation strategies and hold contingency plans for execution close at hand.