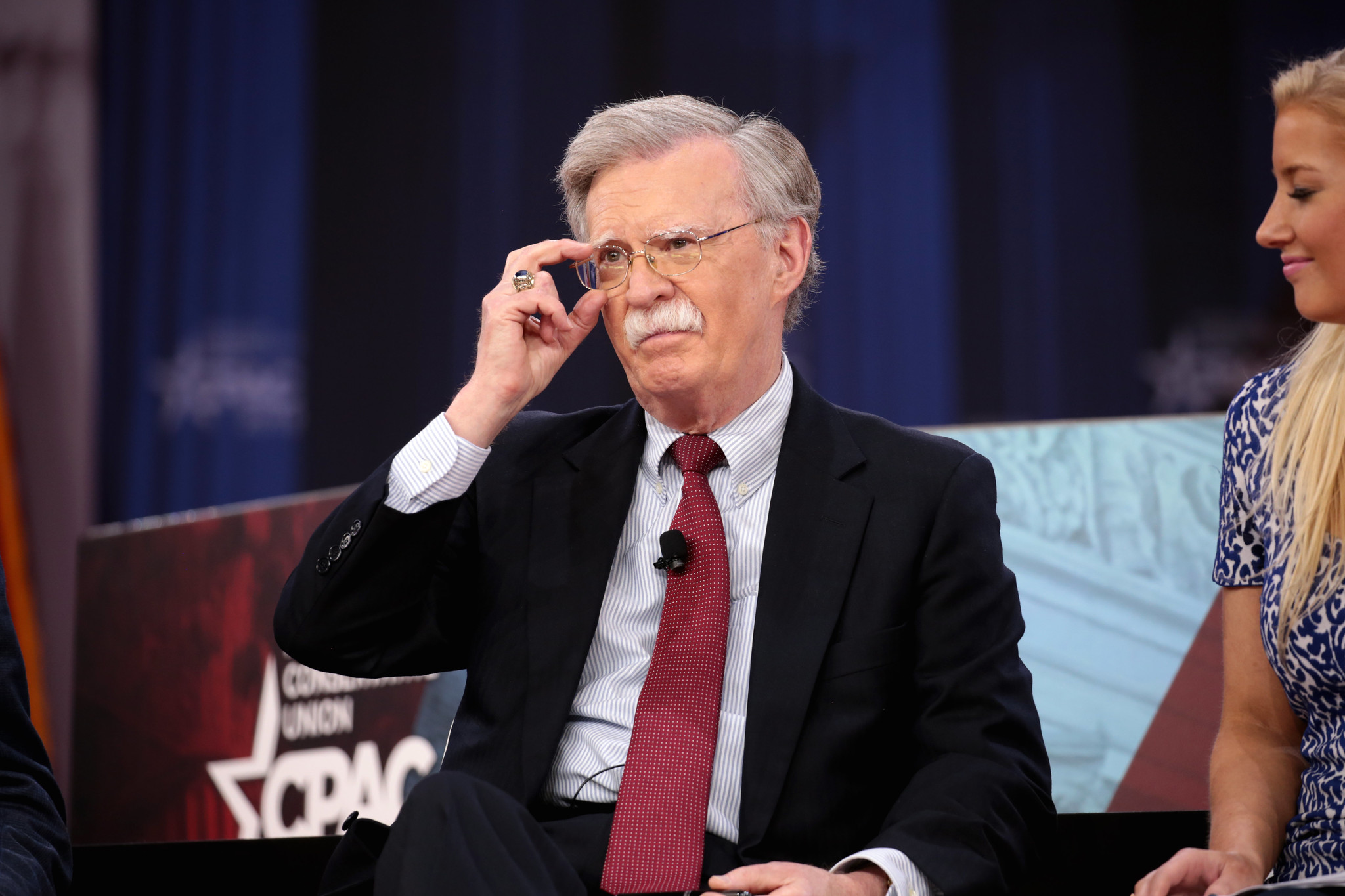

Will the Justice Department Prosecute John Bolton?

Reporting indicates that the Justice Department is conducting a criminal investigation, likely concerning possible publication of classified material in Bolton’s book. But bringing charges would be a politically charged endeavor fraught with legal risks.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In June, former National Security Adviser John Bolton published “The Room Where It Happened,” a tell-all book about his time in the Trump administration—triumphing over efforts by the Justice Department to enjoin the book’s release at the last minute. Now, recent media reporting indicates a grand jury has been impaneled to consider potential criminal charges against Bolton for the publication of his book, seemingly for the crime of unauthorized dissemination of classified information.

Indicting Bolton would be a politically charged endeavor fraught with legal risks. This is even more true following a recent public statement—filed in the government’s separate civil lawsuit against Bolton— that describes political interference by senior White House and National Security Council (NSC) personnel in the government’s review of whether the book contained classified information.

The filing, from former NSC staffer Ellen Knight, provides a detailed account of the prepublication review process for Bolton’s book. Bolton submitted his manuscript to the NSC for prepublication review at the end of December 2019. The process continued for several months, as Bolton coordinated with Knight, the staffer overseeing the review of his manuscript, to remove any portions that still implicated classified information. By the end of April 2020, Knight’s team was confident that the process was reaching its conclusion and verbally conveyed that view to Bolton, although, according to the filing, she was clear that the process was not yet finished. But Knight’s letter describes how, in the subsequent weeks, senior political officials at the White House and within the NSC intervened to overrule her, and ultimately never cleared the book prior to Bolton’s proceeding with publication in late June. Although the government filed a civil lawsuit mere days before the book’s release and sought a temporary restraining order seeking to halt publication, they were rebuffed and the book went public.

It is a well-settled legal precedent that officials who have been granted security clearances (whether they currently hold one or did so in the past) lack a First Amendment right to publish or disseminate properly classified information. As I outlined previously in a Lawfare post addressing the nondisclosure legal parameters in general, security clearance holders are contractually bound for life to ensure they do not disseminate classified information, even after leaving government service. The prepublication review process exists to provide those individuals with a means to secure official government approval verifying that the written work they seek to publish is devoid of classified information. The courts have made clear that if a former clearance holder properly adheres to the prepublication review process, the government may not subsequently censor any unclassified information found in the written work, even if it is politically embarrassing.

Failure to comply with the prepublication review process where mandatory—specifically for those who maintained clearance eligibility for access to Sensitive Compartmented Information—is grounds for the government to pursue a breach of contract civil lawsuit to recover monetary damages. It was in that context that the government filed its civil lawsuit against Bolton, just as it has done countless times over the years with respect to failures by individuals to comply with the prepublication review process. A civil action is far simpler than a criminal prosecution for the government to pursue, as it is a mere breach of contract dispute over monetary royalties. Even in circumstances where issues of “unclean hands” or “bad faith” exist regarding the government’s conduct, the courts have not been willing to permit those defenses to invalidate the civil liability of the former clearance holder. At most, those defenses merely mitigate the scope of monetary royalties the government will be entitled to recover.

A criminal prosecution is a different ballgame, and would likely involve charges under 18 U.S.C. § 793(d) and/or 18 U.S.C. § 798 for disclosing classified information to unauthorized third parties, with potentially years of jail time at stake. I am not aware of the U.S. government ever bringing a criminal case against an individual for unauthorized dissemination of classified information in the context of the prepublication review process. Unlike in a civil suit, where the government only needs to demonstrate a breach of contract, securing a criminal conviction would require the government to demonstrate to the court’s satisfaction that the information at issue was at the time and still remains properly classified. Making such a presentation would necessitate senior government security officials attesting to the classification status of the information in sworn affidavits.

To be sure, the government has been willing to make those sworn attestations to the courts in the past. It has done so in standard “classified leak” cases, such as the one brought against Chelsea Manning for disseminating classified government documents to unauthorized third parties. The closest the government has ever come to bringing criminal charges in the prepublication review context was the prosecution of former CIA official John Kiriakou, whose indictment included a charge under 18 U.S.C. § 1001 for making false statements of material fact to the CIA’s Publications Review Board regarding the fictional status of a classified investigative technique. Kiriakou later pleaded guilty to a separate charge as part of a plea agreement, and this § 1001 charge was dropped.

If the government were to pursue a criminal indictment of Bolton, they would have to confront a problem that first arose in the civil suit: the issue of the first-level classification review by Knight, and the later second level review by NSC Deputy Legal Adviser Michael Ellis that overruled Knight’s original review determination. Although the federal judge overseeing the civil lawsuit was persuaded by classified government declarations—submitted in camera and ex parte only to the judge—that Bolton’s book likely still contained classified information, that assessment was not formalized as a legal conclusion and ultimately could not salvage the government’s futile effort to stop publication of the book in June.

In a criminal case, the issue of politicized intervention by senior NSC and White House officials would rear its ugly head once again. Bolton would have a nontrivial chance of arguing successfully that there is sufficient evidence of bad faith and selective prosecution by the government to warrant dismissing the charges. Specifically, Bolton could point to the detailed statement Knight’s legal team filed recently in his civil lawsuit outlining how her original determination that Bolton’s book had been purged of classified information was overruled by Ellis (who she claims lacked the requisite security expertise) and senior political officials in the White House and NSC. The statement from Knight’s legal team particularly highlighted repeated efforts by Justice Department officials and even Patrick Philbin, the deputy counsel to the president, to pressure her to admit the original review determination was erroneous (something she declined to do).

The government was not required to accept Knight’s original determination before issuing a final letter approving publication of Bolton’s book, and there may be credible arguments the government could outline for how Knight’s conclusions were in fact erroneous. A judge might ultimately conclude that the behind-the-scenes drama outlined by Knight smells foul but is insufficient to dismiss the criminal charges. That said, given the political sensitivity of Bolton’s book—and particularly the details it provided regarding President Trump’s actions toward Ukraine, which eventually precipitated Trump’s impeachment—any federal judge overseeing the criminal proceeding would likely have serious questions about potential bad faith in the government’s actions. This is an area of evidentiary exploration the government would no doubt wish to avoid being aired out in public in any criminal proceeding, even if not ultimately fatal to a potential prosecution of Bolton.

Nor would that be Bolton’s only possible defense. Bolton could also argue that the information in his book identified by the government as classified was material that Bolton himself had deemed unclassified prior to his departure from government service, when he was still a classification authority—that is, an official with the authority to deem material classified or unclassified. Bolton could also point to Trump’s public remarks suggesting that Bolton’s book provided false details about what occurred inside the White House—which raises the question of whether the government can properly classify fictional information.

None of this means a prosecution of Bolton would be guaranteed to fail. It also doesn’t mean that a prosecution should not be pursued if the evidence is there: Bolton has exhibited an immense level of chutzpah in his disregard for the very classification and prepublication review process with which he had demanded compliance by others for years, and it makes sense that he should be held accountable for it. The question is whether the Justice Department is willing to roll the dice and bring its first-ever prosecution in a prepublication review case, even though the case has such clear and unmistakable flaws.

In a normal world, the odds would be in favor of Bolton’s skirting criminal indictment and simply facing civil liability. In the era of Donald Trump, however, nothing is truly out of the realm of possibility