William Barr’s Remarkable Non-Commitments About the Mueller Report

“I don’t think there’ll be a report,” President Trump’s former attorney, John Dowd, recently told ABC News. “I will be shocked if anything regarding the president is made public, other than ‘We’re done.’” Referring to a possible report by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, Dowd suggested Mueller won’t release a detailed public accounting of the results of the investigation because he has nothing on Trump.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

“I don’t think there’ll be a report,” President Trump’s former attorney, John Dowd, recently told ABC News. “I will be shocked if anything regarding the president is made public, other than ‘We’re done.’” Referring to a possible report by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, Dowd suggested Mueller won’t release a detailed public accounting of the results of the investigation because he has nothing on Trump.

Another reason there might not be a public report—or, at least, not much of one—is because William Barr, who will likely be attorney general by the end of the week, might not release one. It is Attorney General Barr’s decision, not Mueller’s, whether to give any information in Mueller’s report to Congress and the public. As we show in this post, Barr in his confirmation hearings committed himself to being transparent, consistent with a strict adherence to applicable laws and regulations. And the applicable laws and regulations require Barr to report very little to Congress or the public.

The Special Counsel Regulations

According to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein’s appointment order, the special counsel regulations “appl[y]” to Mueller’s investigation. It is important to recall that these regulations were designed and implemented against the background of a failed experiment with the independent counsel under the 1978 Ethics in Government Act and the Independent Counsel Reauthorization Act of 1994, and, in particular, the reaction to Ken Starr’s controversial report to Congress concerning his investigation of President Clinton. According to the section-by-section discussion of these regulations by its 1999 drafters in a final rule published to the Federal Register, one of the main aims of reform in the regulations was to rein in reporting about the special counsel investigation:

The principal source of the problems with the Final Report requirement as set forth in the Independent Counsel Act is the fact that the Report typically has been made public, unlike the closing documentation of any other criminal investigation. This single fact both provides an incentive to over-investigate, in order to avoid potential public criticism for not having turned over every stone, and creates potential harm to individual privacy interests.

The special counsel regulations under which Mueller operates reflect these concerns. They give Mueller no authority to issue a report directly to Congress. Rather, under 28 CFR § 600.8, at “the conclusion of [Mueller’s] work,” he “shall provide the Attorney General with a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the Special Counsel.” According to the explainer in the Federal Register, this provision contemplates “a limited reporting requirement . . . , in the form of a summary final report to the Attorney General,” which should be handled as “a confidential document, as are internal documents relating to any federal criminal investigation” (emphasis added). As we explained in our fuller treatment of the regulations, Section 600.8 contemplates a report from the special counsel to the attorney general “akin to the usual internal documentation related to a criminal investigation that does not result in indictment.”

We can imagine Mueller’s report to Barr going beyond a typical declination memorandum. For example, Mueller might have reasons to think Trump violated federal criminal law, but he might be barred from prosecuting Trump in light of the Justice Department’s controlling ruling that the president cannot be indicted. If that is so, Mueller might want to explain to Barr in some detail the reasons for his suspicions about Trump’s possibly illegal actions, especially if those suspicions relate to the subject matter of the counterintelligence investigation—the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia in connection with the 2016 election. Even if Mueller concludes that Trump violated no law, he might want to tell the attorney general quite a lot about the counterintelligence implications of what he learned.

So let us assume that Mueller sends Barr a very lengthy report. At that point, the regulations require Barr to tell Congress or the public very little about the report.

Section 600.9(a)(3) requires Barr to notify Congress about the completion of Mueller’s work and to explain any instances in which Barr concluded that a “proposed action” by Mueller “should not be pursued.” If Barr does not second-guess an action Mueller wants to take, then Barr’s only reporting duty is to tell Congress that Mueller’s work is done. And even if Barr does check an action proposed by Mueller, Barr is supposed to give Congress only a very brief explanation why. As the Justice Department stated in the Federal Register document that accompanied for the regulations: The reports to Congress contemplated by subsection (a) “will be brief notifications, with an outline of the actions and the reasons for them” (emphasis added).

Under subsection (c) of the regulations, Barr is additionally allowed (but not required) to release to the public whatever Mueller reported to Congress, if he determines that public release of the reports to Congress “would be in the public interest,” and even then only “to the extent that release would comply with applicable legal restrictions.”

In sum, even assuming that Mueller sends Barr a detailed report, Barr need only tell Congress that the investigation has ended and briefly explain any restriction he put on Mueller’s proposed course of action. That is all the regulations require Barr to do. There might be ways for Barr to read the law creatively to allow him to do more, as Lawfare writers have noted. We will not repeat those arguments here. The relevant point is that Barr need not do more under the law. (There is a plausible way to read the regulations to not permit Barr to do more, but we will set that aside for present purposes.)

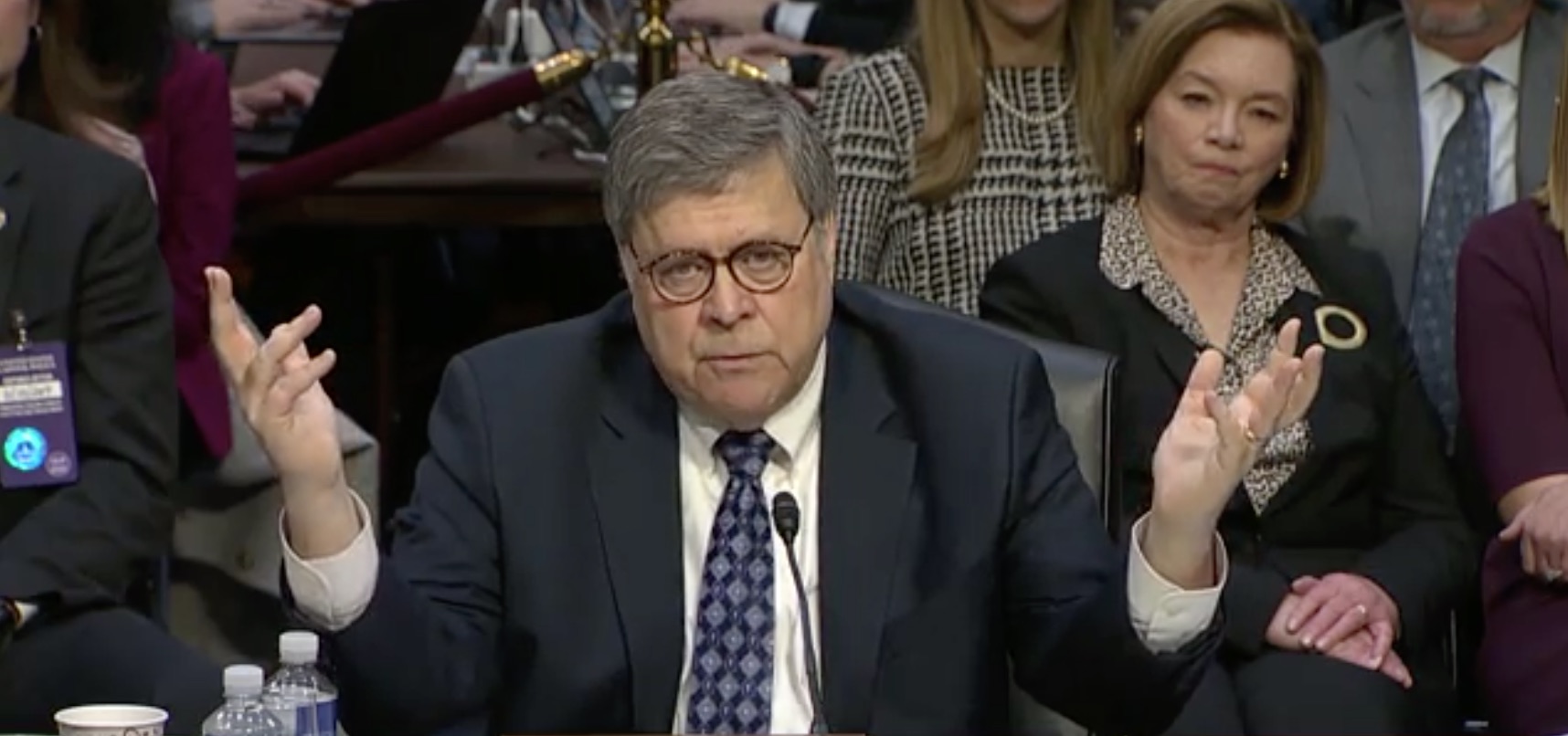

Barr’s Confirmation Hearings

It is against this background that one should read Barr’s very carefully worded responses to senators’ questions at his confirmation hearings.

Barr said this in his opening statement: “I … believe it is very important that the public and Congress be informed of the results of the special counsel’s work. My goal will be to provide as much transparency as I can consistent with the law” (emphasis added).

Barr was then asked repeatedly whether he would share Mueller’s report with Congress. He said over and over again that he would do as much as he could, consistent with pertinent law. Here are the main examples, which we quote at length in order to emphasize just how careful Barr was not to commit to anything beyond what the law requires:

Sen. Lindsey Graham: When his report comes to you, will you share it with us as much as possible?

Barr: Consistent with the regulations and the law, yes.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Will you commit to making any report Mueller produces at the conclusion of his investigation available to Congress and to the public?

Barr: I am going to make as much information available as I can consistent with the rules and regulations that are part of the special counsel regulations. …

Feinstein: Will you provide Mueller’s report to Congress, not your rewrite or a summary?

Barr: Well, the regs do say that Mueller is supposed to do a summary report of his prosecutive and his declination decisions and that they will be handled as a confidential document as are internal documents relating to any federal criminal investigation. Now, I’m not sure—and then the [attorney general] has some flexibility and discretion in terms of the [attorney general]’s report. … [M]y objective and goal is to get as much as I can of the information to congress and the public. These are departmental regulations, and I’m going to be talking to Rod Rosenstein and Bob Mueller. … There’s probably existing thinking in the department as to how to handle this. But all I can say at this stage, because I have no clue as to what’s being planned, is that I am going to try to get the information out there consistent with these regulations and to the extent I have discretion, I will exercise that discretion to do that. (Emphasis added)

Sen. Patrick Leahy: So you’d be in favor of releasing the investigative report when it’s completed?

Barr: As I have said, I’m in favor of as much transparency as there can be with the rules and the law.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: Will you commit to make public all of the report’s conclusions, the Mueller report even if some of the evidence supporting the conclusions can’t be made public?

Barr: That certainly is my goal and intent. It’s hard for me to conceive of a conclusion that would run afoul of the regs as currently written, but that’s certainly my intent.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal: [Will you] commit to explaining to us what the reasons are for your deleting any information that the special counsel includes that you are preventing us or the public from seeing?

Barr: Yeah. That would be my intent. … I don't know what kind of report is being prepared. I have no idea, and I have no idea what Acting Attorney General Rosenstein has discussed with Special Counsel Mueller. If I’m confirmed, I’m going to go in and see what’s being contemplated and what they’ve agreed to, and what their interpretation—you know, what game plan they have in mind … but my purpose is to get as much accurate information out as I can consistent with the regulations.

Sen. Mazie Hirono: So what I'm hearing you say, that in spite of the fact that you want to be transparent, neither Congress nor [the] public will get the Mueller report because that’s confidential. So what we will be getting is your report of the Mueller report. Subject to applicable laws limiting disclosure. So is that what you’re telling us?

Barr: I don't know what—at the end of the day, what will be releasable. I don’t know what Bob Mueller is writing.

Hirono: You said that the Mueller report is confidential pursuant to whatever the regulations are that apply to him. So I’m just trying to get, as to what you’re going to be transparent about?

Barr: As the rules stand now, people should be aware that the rules, I think, say that the independent—the special counsel will prepare a summary report on any prosecutive or declination decisions and that that shall be confidential and shall be treated as any other declination or prosecutive material within the department. In addition, the attorney general is responsible for notifying and reporting certain information upon the conclusion of the investigation. Now how these are going to fit together and what can be gotten out there, I have to wait and—I would have to wait. I’d want to talk to Rod Rosenstein and see what he has discussed with Mueller and what—

Hirono: But you have testified you’d like to make as much of the original report—

Barr: All I can say now is—all I can say right now is my goal and intent is to get as much information out as I can consistent with the regulations.

Sen. John Kennedy: Let’s assume that Mr. Mueller at some point, hopefully soon, writes a report and that report will be given to you. What happens next under the protocol rules and regulations at Justice?

Barr: Well under the current rules, that report is supposed to be confidential and treated as, you know, the prosecution and declination documents in an ordinary—any other criminal case. And then, the attorney general as I understand the rules, would report to Congress about the conclusion of the investigation. I believe there may be discretion there about what the attorney general can put in that report.

Sen. Chris Coons: I didn't hear a concrete commitment about release and I think this is a very significant investigation, and you’ve been very forthcoming about wanting to protect it. The [Justice Department] has released information about declination memos, about descriptions of decisions not to prosecute in the past, I’ll cite the Michael Brown case, for example. Would you allow Special Counsel Mueller to release information about declination memos in the Russia investigation as he sees fit?

Barr: I actually don’t think Mueller would do that because it would be contrary to the regulations, but that’s one of the reasons I want to talk to Mueller and Rosenstein and figure out, you know, what the lay of the land is.

Coons: But if appropriate under current regulations, you wouldn’t have any hesitation about saying prosecutorial decisions should be part of that final report?

Barr: As I said, I want to get out as much as I can under the regulations.

Sen. Thom Tillis: Did you also say … that Special Counsel Mueller [s]hould be allowed to draw this to a conclusion, then he will submit his report and you’re going to do everything that you can to present as much of that information as you can to the extent that confidential information is not being compromised?

Barr: Yeah, to the extent the regulations permit it.

Barr was remarkably—and, in our view, understandably—noncommittal in these statements. He reminded the senators of what the regulations say and noted that he would follow them. He also made clear that he does not know how the Justice Department has interpreted the regulations, or what they might have in mind for getting the Mueller information to Congress or the public. Barr came closest to making a novel commitment when he told Klobuchar that his “goal and intent” would be to “make public all of the report’s conclusions” (emphasis added). However, those conclusions could, consistent with his testimony and the regulations, be as minimal as noting who Mueller decided to prosecute.

We don’t think there is anything untoward in Barr’s responses to the senators. He acted prudently in sticking to the law, especially since, as he noted, he has no idea what Mueller is planning or how the Justice Department interprets the regulations. We simply wish to emphasize that Barr did not commit to making much if any of Mueller’s work available to Congress or the public, and that the regulations Barr wrapped himself in require him to report very little.

In this regard, some other elements of Barr’s testimony are worth considering. Several senators tried to pin down or limit Barr’s discretion vis-a-vis Mueller. For example, Coons tried to get Barr to commit to deferring to Mueller just as Sen. Edward Kennedy got attorney general nominee Elliot Richardson to pledge to defer to the decisions of the special prosecutor during Watergate. Barr would not bite:

Coons: Senator Kennedy followed up by asking Richardson if the special prosecutor would have the complete authority and responsibility for determining whom he prosecuted and at what location. Richardson said simply, yes. Would you give a similar answer?

Barr: No, I would give the answer that’s in the current regulations, which is that the special counsel has, you know, broad discretion but the Acting Attorney General in this case, Rod Rosenstein, can ask him about major decisions. And if they disagree on a major decision, and if after giving great weight to the special counsel’s position, the acting attorney general felt that it was so unwarranted under established policies that it would not be followed, then that would be reported to this committee.

Coons: Senators asked Elliott Richardson what he would do if he disagreed with the special prosecutor. Richardson testified to the committee the special prosecutor’s judgment would prevail. That’s not what you’re saying. You’re saying if you have a difference of opinion with Special Counsel Mueller you won’t necessarily back his decision. You might overrule it?

Barr: Under the regulations there is the possibility of that. … A lot of water has gone under the dam since Elliott Richardson, and a lot of different administrations on both parties have experimented with special counsel arrangements, and the existing rules I think reflect the experience of both Republican and Democratic administrations and strike the right balance. They [were] put together in the Clinton administration after Ken Starr’s investigation.

Also, in exchanges with Coons, Leahy and Blumenthal, Barr emphatically reserved the possibility that valid claims of executive privilege—about which he has strong views—might inform what elements of the Mueller report he makes available to Congress:

Coons: Suppose the prosecutor determines it’s necessary to get the president’s affidavit or to have his testimony personally. Would that be the kind of determination he the special prosecutor could make? Richardson said yes. Will you give a similar answer today that you won’t interfere with Special Counsel Mueller seeking testimony from the president?

Barr: You know, I think, as I say, the regulations currently provide some avenue if there’s some disagreement. I think that in order to overrule Mueller someone would have to—the attorney general or the acting attorney general—would have to determine after giving Mueller’s position great weight, that it was so unwarranted under established policies that it should not be done. So that’s the standard I would apply, but I’m not going to surrender the—the regulations give some responsibility to the attorney general to have this sort of general—not day-to-day supervision, but sort of be there in case something really transcends the established policies. I’m not surrendering that responsibility. I’m not pledging it away.

Leahy: Do you see a case where the president could claim executive privilege and say that parts of the report could not be released?

Barr: I don’t have a clue as to what would be in the report. The report could end up being not very big, I don’t know what’s going to be in the report. In theory if there was executive privilege material to which an executive privilege claim could be made, someone might raise a claim of executive privilege.

Blumenthal: Will you commit that you will allow the special counsel to exercise his judgment on subpoenas that are issued and indictments that he may decide should be brought?

Barr: As I said, I will carry out my responsibilities under the regulations. Under the regulations, the—whoever is attorney general can only overrule the special counsel if the special counsel does something that is so unwarranted under established practice. I am not going to surrender the responsibilities I have. I would—you would not like it if I made some pledge to the president that I was going to exercise my responsibilities in a particular way, and I’m not going to make a pledge to anyone on this committee that I’m going to exercise it in a particular way or surrender it.

Barr’s claims are well within the bounds of the special counsel regulations, as Section 600.7 says that the “Attorney General may request that the Special Counsel provide an explanation for any investigative or prosecutorial step, and may after review conclude that the action is so inappropriate or unwarranted under established Departmental practices that it should not be pursued.” According to the comments in the Federal Register, while the special counsel can exercise independent prosecutorial discretion, “it is intended that ultimate responsibility for the matter and how it is handled will continue to rest with the Attorney General.” In his testimony, Barr refused to make to a firm commitment on executive privilege and correctly noted his role as the final decision-maker in the investigation.

There is a separate question here about whether and how Barr might send information uncovered by Mueller to Congress for purposes of impeachment. The special counsel regulations say “nothing about impeachment referrals one way or the other,” as Quinta Jurecic and Ben Wittes once noted. Whether Barr can refer impeachment material uncovered by Mueller to Congress outside of the scope of the current special counsel regulations is a hard question that we cannot answer today. Remarkably, no one asked Barr about this at his hearing. The Senate did not even try to extract a pledge from Barr about Congress’s entitlement to potential impeachment material. Thus Barr gave no assurances, one way or the other, on that matter.

***

A few weeks ago, Mikhaila Fogel, Jurecic and Wittes summarized what questions the Senate asked of attorney general nominees Elliot Richardson and William Saxbe in the 1970s with respect to the special prosecutors’ investigation of the Watergate matter. They also summarized the extraordinary assurances that those two men gave the Senate about not interfering with the special prosecutors’ work.

The Barr hearings were quite different. The senators tried to pin Barr down, but he refused to let them. He was able to avoid “pledging away” his discretion by invoking the law, including the special counsel regulations, which require him to release very little information to Congress or the public. Barr may well find ways to release a lot of information about the Mueller investigation. But nothing in the special counsel regulations or in his testimony requires him to do that.