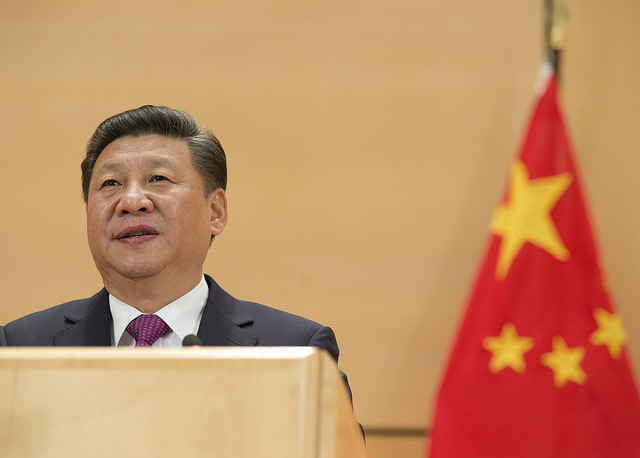

Xi Jinping Amends China's Constitution

The instantaneous reaction to the momentous news that Xi Jinping will be eligible to serve a third term and beyond as chairman of China’s government is the most recent demonstration that we live in a connected world. Domestically, Xi’s bold move to amend his country’s Constitution, although undoubtedly popular with the masses, has clearly generated significant elite opposition.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The instantaneous reaction to the momentous news that Xi Jinping will be eligible to serve a third term and beyond as chairman of China’s government is the most recent demonstration that we live in a connected world. Domestically, Xi’s bold move to amend his country’s Constitution, although undoubtedly popular with the masses, has clearly generated significant elite opposition. This has been visible even in non-transparent China, despite Xi’s stifling of information and free expression. Indeed, adoption of what could be life tenure for Xi apparently inspired considerable opposition even within the secret confines of the Communist Party Central Committee, which reportedly had to be dragooned into supporting his political coup.

The elimination of term limits for what are usually translated into English as China’s presidency and vice-presidency is only one of three crucial constitutional amendments about to be adopted. The other two are the enshrinement of “Xi Jinping Thought” and the formalization of government “supervisory commissions” that will strengthen what should be called the Inquisition with Chinese characteristics. Together they will expand Xi’s already fearsome powers over his countrymen and potentially extend his dictatorship into the indefinite future.

The outside world, until now, has shown insufficient interest in the Xi regime’s shocking violations of the human rights supposedly guaranteed by both Beijing’s Constitution and the more than twenty international legal documents to which the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has surprisingly adhered. Sunday’s announcement, however, has awakened deeper concern about Xi’s steadily increasing repression. Foreign observers, for example, have finally begun to focus on the fact that hundreds of thousands of Muslim Chinese citizens are today detained in “political education” camps designed to destroy their religion and customs—camps suspiciously similar to the “re-education through labor” sites that were ostensibly abolished several years ago.

To be sure, Xi Jinping’s constitutional coup has given the world other more prominent concerns—foremost among them its implications for international security. This electrifying elimination of the formal barrier to Xi’s life tenure as chief of China’s government crystallizes developments over the past five years that have resurrected foreign worries about a “China threat.” It coincides with, and further fuels, the intense criticisms by many American policy makers and foreign affairs experts who now question the premises of Washington’s China policy of the past half century.

Only months ago this attack seemed the monopoly of right-wing critics, egged on by the likes of Steve Bannon, who were preparing to mobilize the nation against the perceived growing power of the Beijing regime. Now the attack—and the resistance it has begun to inspire—have moved to center stage.

I am one of those who, in the late 1960s, urged the Johnson and Nixon administrations to abandon U.S. hostility toward the PRC, even though it was in the throes of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Looking back, I do not think our policy was wrong. Surely continuation of the policy of containment and isolation would have been worse. Of course, different supporters of the then-new policy of luring the PRC into the world community had different primary motivations. Many of us who specialized in Chinese studies were not only interested in the realpolitik of using Beijing to balance Moscow and to extract the U.S. from its mistaken foray into Vietnam. We also believed that ending China’s isolation and promoting its active participation in the world community would be a boon to peace and to the well-being of the long-suffering Chinese people.

That belief has been vindicated by the impressive progress that has been made both in international relations and China’s domestic life since the PRC’s entry into the United Nations in 1971 and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Washington and Beijing in 1979. Now, however, we are confronted by the consequences of success and at a bad time because the helm of the Chinese Communist Party has been seized—perhaps only temporarily—from more moderate leaders. Xi Jinping is a dynamic, able, ruthless and nationalist leader embarked on a mission to restore the greatness of the “central realm” after two centuries of felt inferiority and grievous struggle.

Xi is a risk-taker with a vision backed by a coherent, long-run strategy and tactics to match. His endless speech to the 19th Party Congress last October is a document worthy of serious attention. It showed no interest in either human rights or international law but is destined to have a huge impact both at home and abroad. At the time, Steve Bannon—by then no longer an adviser to the president but still a prominent voice on the right—called it "the single most important speech of the twenty-first century."

The sudden prospect of Xi’s indefinite rule may have a stunning effect on the American public comparable to the Soviet Union’s successful launching of Sputnik. In China its impact on the educated classes may approach that of the Party’s June 4, 1989 military slaughter of students, workers and intellectuals near Tiananmen Square. There has already been a spike in Chinese interest in emigration, and many of the hundreds of thousands of Chinese students in North America, Europe, Australia and other countries appear to have been jolted into reconsidering their plans to soon return home. To the extent we are allowed to know, Xi, a master of propaganda, remains broadly popular with the less-educated population despite growing dissatisfaction with the income inequality, rural-urban divide, labor conditions, real estate bubble, horrendous pollution, male-female imbalance and other problems that trigger the sense of injustice and an extraordinary number of “mass incidents.”

Of course, many Western observers hope that America’s response to this week’s news will stimulate not only abandonment of President Trump’s pathetic and costly attempts at foreign policy but also a resurgence of bipartisan support for strengthening the cooperation of democratic nations and the further development of international institutions and practices capable of meeting Beijing’s political, military, economic, diplomatic and human rights challenges in firm but fair and reasonable ways.

Those challenges may not turn out to be as fearsome as widely anticipated. China’s liabilities are increasing more rapidly, although less obviously, than its assets. This is surely one of the major factors that has led Xi Jinping to play the role of the merciless dictator vigorously suppressing and unfairly punishing mere domestic criticism as well as overt dissent.

Yet it has proved impossible for him to completely hide the difficulties that his bid to end term limits has encountered, even within the Party’s loyal Central Committee. China watchers will now focus on the size of the vote by which the upcoming National People’s Congress (NPC) approves the Party’s proposal to amend the Constitution. Will there be only a handful of token dissenters, just enough to give the appearance of a credible free vote and overwhelming support for Xi’s bid for unrestricted power? Or will there be one hundred or more negative votes or abstentions, as there sometimes have been for the annual reports to the NPC of the Supreme People’s Procuracy and the Supreme People’s Court in protest against blatant failures to honor the rule of law? If a significant minority of the NPC’s roughly 3,000 delegates should muster the courage to register their open disagreement, will their vote be revealed in accordance with customary practice? Or will the published result be doctored to save Xi Jinping’s face?

Experience suggests that the Chinese equivalent of intense lobbying must be under way as the NPC session unfolds, in order to assure the Party leadership’s desired outcome. Skilled Party minions have many tools for enforcing the leadership line through combinations of intimidation and persuasion. Yet, as the process of enacting a number of controversial statutes has demonstrated in recent decades, it is no longer entirely accurate to dismiss the NPC as “China’s rubber-stamp legislature.”

Whatever the vote, it is already clear that Xi Jinping is paying a high price at home as well as abroad for his understandable wish to avoid becoming a final-term lame duck. Although the anticipated constitutional amendment will add to his power in the short run, it is likely, as many predict, to produce greater political instability before long. If the supreme leader fails to cope with the problems that he will inevitably confront in the next few years, his constituents will know whom to blame, and rivals will be all too eager to seize the advantage.

There is especially high risk of an important mistake in international affairs. Xi, for example, may overplay his current efforts to increase pressures on Taiwan to rejoin the Motherland before the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party’s 1921 founding. A shootout with the U.S. in the South China Sea could also have embarrassing reverberations, as could chaos or war on the Korean Peninsula. We should not assume that the new possibility that Xi can continue to lead the government after 2023 means that he is necessarily destined to do so. As Matthew Arnold wrote long ago, “Only the event will teach us in its hour.”