Ideology à la Carte: Why Lone Actor Terrorists Choose and Fuse Ideologies

Editor's Note: The succession of so-called "Lone Wolf" attacks that have hit America in the last year have generated a wave of panic about the Islamic State's global reach. Yet many of the individuals seem more confused losers than religious fanatics. In assessing this phenomenon, Paige Pascarelli of Boston University argues that we are looking in the wrong place. She contends that many of terrorists fuse the personal and the political, and looking at the teachings of a specific group offers us little understanding.

***

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor's Note: The succession of so-called "Lone Wolf" attacks that have hit America in the last year have generated a wave of panic about the Islamic State's global reach. Yet many of the individuals seem more confused losers than religious fanatics. In assessing this phenomenon, Paige Pascarelli of Boston University argues that we are looking in the wrong place. She contends that many of terrorists fuse the personal and the political, and looking at the teachings of a specific group offers us little understanding.

***

As details emerge about the recent arrest of Ahmad Rahami, the man who is charged with planting numerous bombs in New York and New Jersey, one facet of the case seems obvious: the man’s ideological inspiration does not place him neatly within one terrorist group.

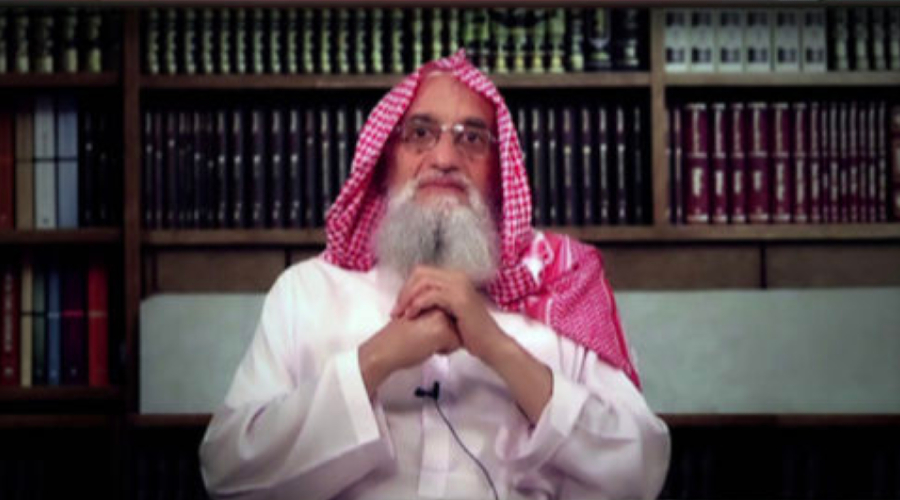

Evidence from Rahami’s journal paints a complex portrait of the man’s relationship with the broader jihadist movement, citing a constellation of groups: his praise for Anwar al-Awlaki and Osama bin Laden suggests he could be sympathetic to al-Qaeda’s aims, but he also uses language consistent with calls to action by deceased ISIS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani. Rahami’s journal also expresses frustration towards the persecution of jihadists in Palestine and anger at U.S. “slaughter” of mujahideen in Afghanistan.

Rahami isn’t alone in his murky ties to multiple jihadist organizations. The case of Orlando shooter Omar Mateen offers striking parallels. Mateen pledged his allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and expressed support for its rival, Jabhat al-Nusra (which recently renamed itself Jabhat Fatah al-Sham). Mateen had even previously boasted that he was a Hezbollah member. Mateen’s endorsements were perplexing because ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra, and Hezbollah are politically (and especially in the case of Hezbollah, ideologically) at odds with one another.

While Mateen was more explicit in his contradictory claims, Rahami and Mateen are not alone in this trend. Despite plotting with conspirators, Asia Siddiqui was arrested in April 2015 for a conspiracy to commit a terrorist attack on her own. Like Mateen, her ideology remained within broader jihadi-Islamist movements but fused ISIS and al-Qaeda philosophies. Blending ideologies for tactical benefit is an evidenced phenomenon as well and is particularly relevant in analysis of the Charlie Hebdo and Kosher market attacks that consisted of both ISIS and AQI attackers likely working together. The differences between both groups appeared to matter little to European jihadists, who found the feud “distant, annoying, and counterproductive.”

More recently, 18-year-old Mahin Khan, a self-proclaimed “American jihadist,” was arrested on terrorism-related charges linking him to a conspiracy targeting Arizona government buildings. Although information about his case is still emerging, evidence suggests that Khan claimed to support both ISIS and the Pakistani Taliban. The broad proclamation of claiming to be a “jihadi” eclipsed his alleged support for truly ideologically conflicting groups.

This sampling of examples highlights a trend of violent lone actors whose ideologies are broadly jihadist, but not tied to any one group.

This sampling of examples highlights a trend of violent lone actors whose ideologies are broadly jihadist, but not tied to any one group. Even so, in the case of Mateen, security officials and policymakers rushed to identify Mateen’s alignment with a specific group. The temptation to classify Mateen within one organization’s particular ideological prism outweighed an objective assessment of the problem: Mateen fused multiple group affiliation and ideologies to motivate his actions. As far as categorization goes, Mateen’s case suggests that group affiliation matters less than his broader commitment his idea of jihad. In this capacity, Mateen’s statements and sentiments are not outliers or rarities in lone actor extremist violence, nor are they as confusing as they seem; individuals tend to blend group affiliation and ideological motivations, which is a significant, recurring, and surprisingly understudied phenomenon. Indeed, if anything, Rahami’s case confirms that this phenomenon is not rare.

Nevertheless, the tendency to try and place all violent lone actors neatly within one extremist group is understandable, because law enforcement must assess the threat and determine if attackers have links to a broader network. Further, group affiliation often informs the rationale behind the attack, including possible motives. Without a clear ideology, motives become more ambiguous and less predictable, more about psychology than national security.

Choosing and fusing is particularly prevalent among the lone actors and wannabes. In fact, recent evidence suggests that lone actors, including small cohorts, are more likely to pick and choose their affiliations and ideologies even if they remain largely “jihadi.” It is, therefore, neither surprising nor abnormal that lone actors do not clearly adhere to any one group’s ideology – but it poses a danger nonetheless.

Academics that study the connection between lone actors and ideological fusion show that lone actors tend to conflate personal grievances with terrorist ideologies, “combining aversion with religion, society, or politics with a personal frustration.” Thus ascribing to one group’s affiliation and ideology is only of peripheral importance. In the absence of a network, where authorities can provide strict and clear guidelines and a social group to reinforce and perpetuate them, lone actors have the freedom to create their own worldview. Any violent trajectory their thoughts or actions might take remains largely unaffected or undeterred by social influences around them.

Ideological fusion entails blending seemingly different elements and beliefs from often competing organizations within the same broader ideological framework; Omar Mateen had fused various ideologies within the context of Islamist radicalism. Despite such inconsistencies, Mateen’s tailor-made ideology remained tethered to global radical Islamist movements and gave him a personalized justification for violence. As a jihadi wannabe, it mattered little to him that such groups, in fact, compete with one another on the ground or, more so in the case of Hezbollah, have fundamentally disparate ideologies. But Mateen wasn’t in Syria or Iraq, and he likely had little or no connection with other like-minded individuals in Florida. Broadly ascribing to jihadi ideology was a means to a very violent end.

The cases highlighted above show how one’s personal ideology may be less of a conscious decision and more aligned with the ebb and flow of popular movements – the flavor(s) of the day. Ultimately, the general connection to jihad is the overarching motivation.

Without a clear ideology, motives become more ambiguous and less predictable, more about psychology than national security.

But, in some cases, the process of fashioning a personal ideology helps to create a measure of certainty and stability amid chaos, whether external or internal, real or imagined. The case of Norwegian Anders Breivik, the lone terrorist who attacked a leftist camp for children in 2011, proves that fusion isn’t limited to jihadists. Behind the mass murder was a meticulously crafted 1,500-page manifesto detailing his self-made ideologies, which included pieces of white supremacism, ultra-nationalism, anti-Islam rhetoric, and Christian fundamentalism. The entirely new ideology he created still resides in the far-right in what’s known as a “new doctrine of civilizational war.” In Breivik’s chaotic mind, he was aware that he did not cleanly fit into any ideological box. It made sense to Breivik; for him, it validated the killing of 77 people.

These cases highlight the many ways individuals can patch together pieces of various and sometimes incompatible ideologies, sometimes deriving from competing groups. But more importantly, they demonstrate how this phenomenon makes lone actors or small groups dangerously unpredictable precisely because they don’t fit in pre-existing boxes.

Whether it’s selected or fused together, “ideology à la carte” is a growing problem. It further obscures an already amorphous, intangible threat that enables individuals to fashion their own justifications for violence. Its connection to lone actor terrorists and small cohorts means that it deserves the attention of law enforcement and counter-extremism actors for the simple fact that incidents of lone actor violence are on the rise. But violent ideology does not simply cause terrorism; as an enabling factor, ideology tends to sit atop a host of underlying root causes. Thus, fighting ideology itself would be a futile exercise. Moreover, the fact that these ideologies are so broad, suggests that trying to understand and counter them through a specific ideological lens would be misleading and counterproductive.

Ideology itself is a far too elusive enemy. It is and will continue to be extremely difficult to mitigate something so intangibly threatening, and such voices and messages will always be waiting in the wings. If wannabes or lone actors who operate outside a network or group don’t care that they are pulling from different groups, then perhaps we shouldn’t either. This undoubtedly will make the job of law enforcement and counter-terrorism officials significantly more difficult. But a focus on individual motivations and grievances, rather than on group allegiances, could offer a more preventive model that will outmaneuver transitory ideological influences.