Securing Phones - and Securing US

Apple has encrypted its iPhone6 for real, that is, removing the backdoor for government warrants. The FBI is erupting, claiming that that this will create problems for law enforcement, raising the specter of not being able to investigate terrorist activities, solve murder cases, and arrest child pornographers.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Apple has encrypted its iPhone6 for real, that is, removing the backdoor for government warrants. The FBI is erupting, claiming that that this will create problems for law enforcement, raising the specter of not being able to investigate terrorist activities, solve murder cases, and arrest child pornographers. In fact, Apple's decision to remove the backdoor on the iPhone's encryption, and Google's decision to have Android encryption on by default, is long overdue. It is the only sensible decision for security.

During the 1990s, we fought the Crypto Wars. The NSA and FBI opposed public use of strong cryptography. Using export controls, the government essentially prevented domestic use. But in a nation — and world — increasingly dependent on electronic communications, preventing the use of encryption made no sense. That's why eighteen years ago, a National Academies report on cryptography policy observed that, "On balance, the advantages of more widespread use of cryptography outweigh the disadvantages," and concluded, "No law should bar the manufacture, sale, or use of any form of encryption within the United States."

Fourteen years ago the US government, with NSA's concurrence, ended export controls on products including strong forms of cryptography. The result was the flourishing of Internet commerce. And — at least a decade later than they should have — US companies began putting security protections into software and hardware products.

The FBI opposed the ending of cryptography controls in 2000, and it now opposes the widespread use of cryptography. But the crime-fighting agency has never really understood that the widespread use of cryptography is essential in a world for which, increasingly, the most important assets are electronic.

Threats to the US come in many forms: nation states stealing US industrial and military secrets, terrorists attacking outside the US and seeking to do so within, criminals using new-fashioned methods to break into government, corporate, and people's accounts. For the better part of a decade, we've been hearing about cyberthreats. In 2010 Deputy Director of Defense William Lynn wrote that the threat to intellectual property — products and processes, business plans, etc. — "may be the most significant cyberthreat that the United States will face over the long term."

How do you protect US assets? Cryptography is necessary. What do you protect? Every communications and storage device people use: computers, laptops, tablets, iPads, telephones, cell phones, smart phones. And you design the security system so that no unauthorized user can break in. That means no hacker, not a different nation state — and not your own.

Is the FBI upset? Of course. For a dozen years, law enforcement has been in a golden age of easily tapped phones that revealed increasingly personal information about users. Despite encryption, some of that information, such as users' location and connection data, will remain accessible to law enforcement (the phone companies will have it). Such transactional information is remarkably revealing to investigators: it shows who is talking with whom, where the bad guys are, who they are with. Access to such information has enabled the US Marshals Service, which tracks fugitives, to cut the average time to locate the criminals from forty-two days to two. And any information that's backed up to the cloud — emails, your searches, etc. — will be present at the cloud provider, still obtainable by law enforcement.

Yes, the decision to secure the content of iPhones (cryptography without backdoors) and Androids (cryptography on by default) will make investigations of low-level drug dealers and other criminals more complicated for law enforcement, especially for those forces with fewer technical capabilities. There are solutions, including using vulnerabilities (under warrant procedures), to tap phones. State and local law enforcement won't have the technical expertise to do this, and the FBI will need to share its skills.

Terrorists are a different situation, of course. But the smart ones, like the most advanced criminal groups (think Zetas), have been using strong security measures, including cryptography, for years. The NSA has used various skillful means to listen in, and it will continue to do so.

The bottom line is the same as in 1996, when the National Academies issued its report. We're more secure with the wide use of strong cryptography — and that means cryptography without back doors. The moves by Apple and Google are very positive steps for security; arguing otherwise is taking a short-term view for our safety and security — to the peril of all.

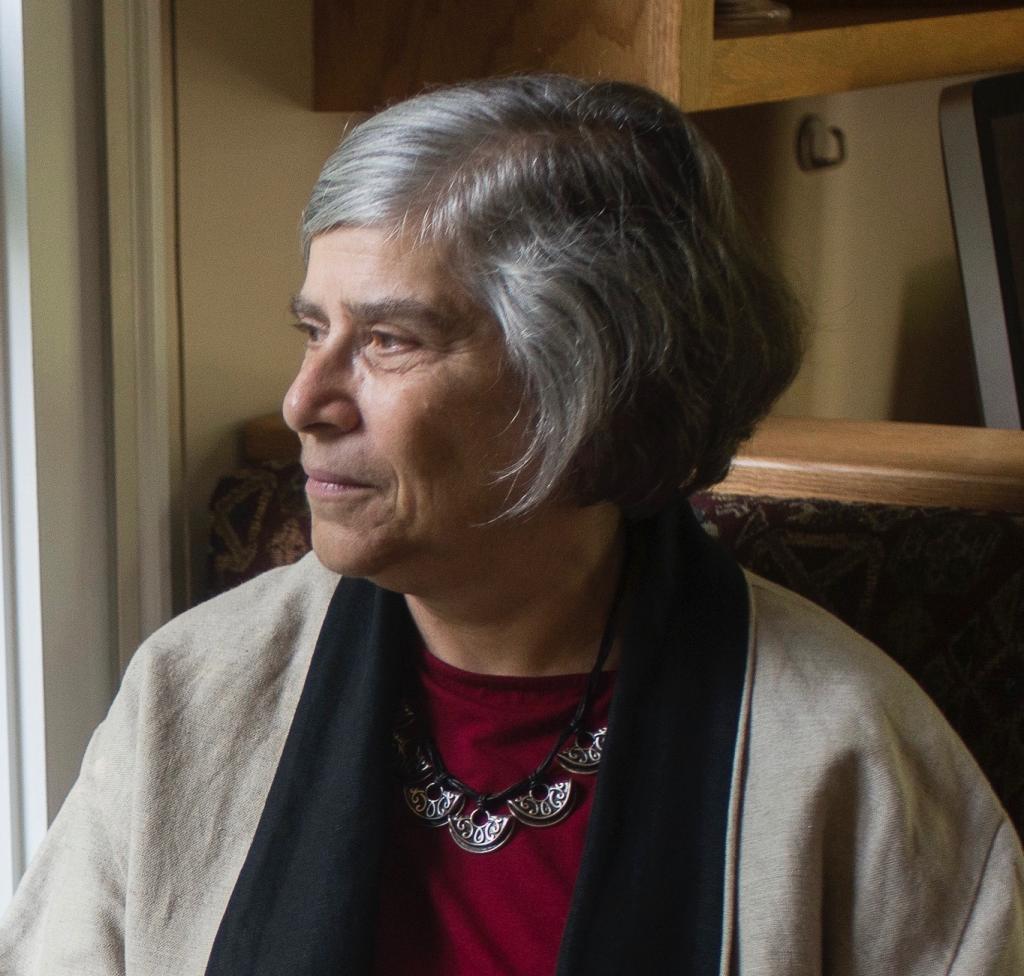

Susan Landau is a Professor of Cybersecurity Policy at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Previously she was a Senior Staff Privacy Analyst at Google and a Distinguished Engineer at Sun Microsystems, and has taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and at Wesleyan University. She is the author of Surveillance or Security? The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies (MIT Press, 2011) and co-author, with Whitfield Diffie, of Privacy on the Line: The Politics of Wiretapping and Encryption (MIT Press, rev. ed. 2007).

Susan Landau is Professor of Cyber Security and Policy in Computer Science, Tufts University. Previously, as Bridge Professor of Cyber Security and Policy at The Fletcher School and School of Engineering, Department of Computer Science, Landau established an innovative MS degree in Cybersecurity and Public Policy joint between the schools. She has been a senior staff privacy analyst at Google, distinguished engineer at Sun Microsystems, and faculty at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Wesleyan University. She has served at various boards at the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine and for several government agencies. She is the author or co-author of four books and numerous research papers. She has received the USENIX Lifetime Achievement Award, shared with Steven Bellovin and Matt Blaze, and the American Mathematical Society's Bertrand Russell Prize.

.png?sfvrsn=2f011ea5_5)