What Is and Isn’t New in the Unredacted Footnotes From the Inspector General’s Russia Report

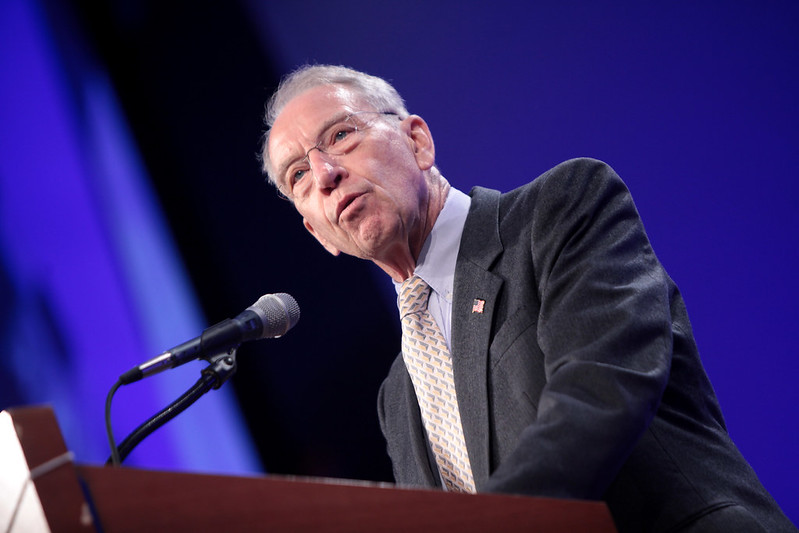

Recently declassified material sheds new light on what the FBI knew about some information in the Steele dossier. But despite the suggestions of Sens. Chuck Grassley and Ron Johnson, it doesn’t discredit the Mueller investigation.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

At the request of Republican Sens. Chuck Grassley and Ron Johnson, the Trump administration recently declassified portions of footnotes in the Justice Department inspector general’s report on the early stages of the FBI’s Trump-Russia investigation. The report, issued in December 2019, found no evidence of political bias against Trump, as the president and his supporters had alleged—but it uncovered a pattern of omissions, errors and inconsistencies in the government’s Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) applications to surveil former Trump campaign aide Carter Page.

Grassley and Johnson’s efforts have focused on information contained in four footnotes. On April 10, the senators announced that the administration had made public parts of three of those footnotes—numbers 302, 334 and 350. Then, on April 15, they drew attention to the release of parts of the fourth footnote—number 342—along with the lifting of redactions in more than 30 other footnotes.

The senators initially declared that the new material was a bombshell. According to their April 10 press release, the footnotes “confirmed” that the Steele dossier, parts of which the FBI relied on to target Page, was the product of a Russian disinformation campaign. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Johnson wrote: “Now it’s been revealed the FBI had evidence that [the Steele dossier] was based in substantial part on a Russian disinformation campaign.” The senators also suggested that the new material tainted Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation. In a tweet, Grassley charged:

These notes beg question of when FBI learned of Russian disinfo in dossier+what did they do about it?? Why did they keep renewing spying authority with this info? What did Mueller know and when? Did we even need Mueller?

— ChuckGrassley (@ChuckGrassley) April 10, 2020

More unmasking to come

Johnson voiced a similar doubt about the Mueller investigation in his op-ed. While Grassley and Johnson have not fully spelled out their argument, they seemed to suggest that because—in their view—the FBI’s investigation was infected with Russian disinformation, the Mueller investigation, which took over the FBI’s Russia probe, was fatally flawed.

The senators’ April 15 press release, however, made far narrower claims. They did not repeat their allegation that the new footnotes confirm that the Steele dossier included information planted by the Russians. Instead, they excoriated the FBI for relying on the Steele dossier after receiving “multiple reports in 2017 warning that [its] claims ... were ‘false’ and ‘part of a Russian disinformation campaign.’” And their only mention of Mueller was to fault him for failing to “examine and investigate corruption at the FBI, the sources of the Steele dossier, how it was disseminated, and reporting that it contained Russian disinformation.”

The senators’ second press release is a more accurate characterization of the four key footnotes than was their first press release. The footnotes do not confirm that the Steele dossier was the product of Russian disinformation. But two footnotes do indicate that the FBI received reports alleging that portions of Steele’s evidence were the product of a Russian disinformation plot—though the footnotes do not establish that these reports were credible. The other two footnotes offer further reason to question the veracity of Steele’s reporting, but they do not necessarily implicate the existence of a Russian disinformation operation.

Additionally, the footnotes on their own do not fundamentally undermine the integrity of the Mueller report. As discussed below, the Steele dossier played no role in the origins of the FBI probe that was transferred to Mueller when he was appointed special counsel in May 2017. Moreover, whether or not Russian operatives targeted Steele has no bearing on Mueller’s conclusion that the Russian government interfered in the 2016 election. (In fact, if Russia did use Steele in an influence operation, that would only be further evidence of Russian interference in the U.S. election.)

Though the Mueller report contains passing references to the Steele dossier at several points, the report does not include any examination of the dossier’s origins—which is perhaps unsurprising, given Mueller’s seemingly narrow understanding of his mandate. As the report states, “The Special Counsel's Office exercised its judgment regarding what to investigate and did not, for instance, investigate every public report of a contact between the Trump Campaign and Russian-affiliated individuals and entities.” When Mueller testified before Congress in July 2019, he said that he was “unable” to address questions related to the Steele dossier as they were “the subject of ongoing review” by the Justice Department. Presumably, Mueller was referring to the inspector general’s probe, which was announced in March 2018.

Background

To understand the relevance of the footnotes, some brief background is necessary. In June 2016, the Washington-based investigative firm Fusion GPS hired former British intelligence officer Christopher Steele—on behalf of the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee—to uncover whatever potentially damaging information Steele could find about then-candidate Trump. Starting in July 2016, the FBI directly obtained numerous reports from Steele—collectively known as the much-discussed “Steele dossier”—which the bureau attempted to verify. (Ultimately, according to the inspector general, “the FBI concluded ... that ... much of the material in the Steele election reports ... could not be corroborated; that certain allegations were inaccurate or inconsistent with information gathered by the [FBI]; and that the limited information that was corroborated related to time, location, and title information, much of which was publicly available.”) On July 31, 2016, the FBI opened its Russia investigation—named Crossfire Hurricane—based on intelligence received from a friendly foreign government. While Steele first provided information to an FBI agent in Europe in early July, the inspector general concluded that Steele’s information did not reach the Crossfire Hurricane team until September and that it was not a part of the FBI’s decision to open the investigation.

The Steele dossier has been the source of significant controversy. Among other things, the government relied on parts of the dossier in its FISA applications targeting Carter Page, who at one point served as a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign. The initial Page application was approved on Oct. 21, 2016—a month after Page left the campaign—and was subsequently renewed three additional times. (The inspector general’s report states that the “salacious and unverified” portion of the dossier, concerning alleged sexual conduct involving the future president, was not included in any of the FISA applications.)

According to the inspector general’s report, Steele “was not the originating source of any of the factual information in his reporting.” Instead, “Steele relied on a primary sub-source (Primary Sub-source) for information, and this Primary Sub-source used a network of [further] sub-sources to gather the information that was relayed to Steele.” It appears that the nature of this relationship was disclosed in the FISA applications. The inspector general’s report noted that:

Ultimately, the initial drafts provided to [Justice Department] management, the read copy, and the final application submitted to the FISC [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court] contained a description of the source network that included the fact that Steele relied upon a Primary Sub-source who used a network of sub-sources, and that neither Steele nor the Primary Sub-source had direct access to the information being reported. The drafts, read copy, and final application also contained a separate footnote on each sub-source with a brief description of his/her position or access to the information he/she was reporting.

Top FBI official Bill Priestap told the inspector general that the bureau never took Steele’s information at “face value.” Priestap and another FBI official, Peter Strzok, said that “the assessment [of Steele’s reports] involved determining the credibility of Steele, including understanding his record of furnishing reliable information, motivation, and possible biases; and verifying the information he provided through independent sources.” Nonetheless, while Steele told inspector general investigators that “his election reports should not have been treated as facts or allegations but as the starting point for further investigation,” the inspector general concluded that there was “no evidence that Steele communicated this view of his reporting to [Steele’s FBI handling agent in Europe] or members of the Crossfire Hurricane team.”

Footnote 302

The newly unredacted footnote 302 makes clear that an individual whom the inspector general report described as “a key Steele sub-source” may have had ties to the Russian government. According to “a document circulated among Crossfire Hurricane team members and supervisors in early October 2016,” the individual, referred to a Person 1, had “historical contact with persons and entities suspected of being linked to [Russian Intelligence Services (RIS)].” The footnote continues: “The document described reporting that Person 1 ‘was rumored to be a former KGB/SVR officer.’” In addition, the footnote establishes that Glenn Simpson, the head of Fusion GPS, told senior Justice Department official Bruce Ohr that he “had assessed that Person 1 was a RIS officer who was central in connecting Trump to Russia”—and that Ohr had passed that information to a FBI special agent working on the investigation.

Because the FISA applications relied extensively on information attributed to Person 1, that individual’s credibility was critical to the government’s ability to establish probable cause and thereby obtain the FISA warrants. More specifically, the inspector general’s report concluded that Person 1 was likely the source of the “most descriptive information in the FISA application of alleged coordination between Page and Russia.” Among other things, the FISA application relied on Person 1 for the allegations that there was “a well-developed conspiracy of co-operation” between the Trump campaign and Russian leadership and that Russia was behind the leak of the Democratic National Committee emails to WikiLeaks with the “full knowledge and support of” of Trump and his campaign team.

Grassley and Johnson make clear that they believe that the government should have disclosed Person 1’s ties to Russia to the FISC. Their claim is generally consistent with the inspector general’s report. While the inspector general did not explicitly fault the government for failing to disclose Person 1’s potential Russia links, the report does express strong concern about the FBI’s failure to disclose, in the renewal applications, information the bureau learned that seriously undermined the credibility of allegations attributed to Person 1.

In addition, in the first statement, Grassley and Johnson also seemed to suggest that Person 1’s Russia ties confirmed that any information attributed to Person 1 was part of a Russia disinformation campaign. But that conclusion does not necessarily follow from the new footnote. In fact, it seems unremarkable—and even expected—that a Steele sub-source would have connections to the Russian government. And even if the allegations about Person 1’s Russia links are accurate, that alone does not prove that the information the sub-source provided was false.

Footnote 334

The new material revealed in footnote 334 establishes that a person identified as Steele’s “Primary Sub-source,” in an interview with the FBI in 2017, “stated that he/she did not view his/her contacts as a network of sources but rather friends with whom he/she has conversations about current events and government relations.” The next sentence in the footnote remains redacted.

The senators focus on this footnote because it likely reveals an inconsistency between the government’s representation of Steele’s Primary Sub-source to the FISC and how the Primary Sub-source perceived his or her contacts. Their allegation that the FBI should have disclosed information learned from its interview with the Primary Sub-source is in line with the inspector general’s conclusion that the FBI’s failure to disclose details related to its interview with the Primary Sub-source was “among the most serious omissions of information.”

It is far less clear that the potential lack of credibility of the Steele dossier suggests that Steele was unwittingly used by the Russian government. There are many reasons other than a Russian disinformation campaign that could explain why Steele and the Primary Sub-source would offer divergent characterizations of the sources of information. As one analyst told the inspector general, the inconsistency could be attributed to factors including:

miscommunications between Steele and the Primary Sub-source, exaggerations or misrepresentations by Steele about the information he obtained, or misrepresentations by the Primary Sub-source and/or sub-sources when questioned by the FBI about the information they conveyed to Steele or the Primary Sub-Source.

Footnotes 342 and 350

Footnotes 342 and 350 most directly implicate whether the Steele dossier could have been part of a Russian disinformation operation.

Footnote 342 reveals that the FBI received information that suggested that the Russians might have tried to corrupt Steele’s reporting. While much of the footnote remains redacted, it reads: “In late January 2017, a member of the Crossfire Hurricane team received information [REDACTED] that RIS may have targeted Orbis,” the name of Steele’s consulting firm. After more redactions, the footnote’s final sentence reveals that “an early June 2017 [U.S. intelligence community] report indicated that two persons affiliated with RIS were aware of Steele’s election investigation in early July 2016. The [FBI] Supervisory Intel Analyst told us he was aware of these reports, but that he had no information as of June 2017 that Steele's election reporting source network had been penetrated or compromised.”

Footnote 350 discloses that the Crossfire Hurricane team received multiple reports, from a redacted source or sources, “indicating the potential for Russian disinformation influencing Steele’s election reporting.” It reveals that the FBI received a January 2017 report from a redacted source that noted an “inaccuracy in a limited subset of Steele’s reporting about the activities of Michael Cohen.” It appears that the same report suggested that the inaccuracies were “part of a Russian disinformation campaign to denigrate U.S. foreign relations.” In a “second report” from a redacted source, an individual “named in the limited subset of Steele’s reporting had denied [certain] representations” in the Steele dossier and a redacted source subsequently assessed that the individual’s denials were “truthful.” And the FBI received a third report, dated February 27, 2017, from the U.S. intelligence community. That report “contained information about an individual with reported connections to Trump and Russia who claimed that the public reporting about the details of Trump’s sexual activities in Moscow during a trip in 2013 were false, and that they were the product of RIS ‘infiltrate[ing] a source into [Steele’s] network.’” However, a redacted source “noted that it had no information indicating that the individual had special access to RIS activities or information.”

The new information in the two footnotes does not support the senators’ initial claim that the footnotes confirm the existence of a Russian operation to disrupt the FBI’s investigation. The footnotes only establish that the FBI received certain reports. The veracity of the information also remains unconfirmed. Many sources are redacted, making the reports difficult to evaluate. And, while it may be significant that the FBI received reports from the intelligence community, the footnotes do not suggest that the intelligence community endorsed the theory that the Steele dossier was part of a Russian campaign.

According to Priestap, the FBI considered the possibility of a Russian disinformation campaign when it evaluated the Steele dossier. He told the inspector general:

[W]e had a lot of concurrent efforts to try to understand, is [the reporting] true or not, and if it’s not, you know, why is it not? Is it the motivation of [Steele] or one of his sources, meaning [Steele’s] sources? ... [Or were they] flipped, they’re actually working for the Russians, and providing disinformation? We considered all of that.

Priestap also added that he found implausible the theory that Russia—through an individual referred to in the report as “Russian Oligarch 1,” with whom Steele may have had a connection—used Steele as part of a disinformation campaign. He told the inspector general that he has

tried to explain to anybody who will listen is if that’s the theory [that Russian Oligarch 1 ran a disinformation campaign through [Steele] to the FBI], then I’m struggling with what the goal was. So, because, obviously, what [Steele] reported was not helpful, you could argue, to then [candidate] Trump. And if you guys recall, nobody thought then candidate Trump was going to win the election. Why the Russians, and [Russian Oligarch 1] is supposed to be close, very close to the Kremlin, why the Russians would try to denigrate an opponent that the intel community later said they were in favor of who didn't really have a chance at winning, I’m struggling, with, when you know the Russians, and this I know from my Intelligence Community work: they favored Trump, they’re trying to denigrate Clinton, and they wanted to sow chaos. I don’t know why you’d run a disinformation campaign to denigrate Trump on the side.

Nonetheless, the inspector general’s report did find that the FBI did not do an adequate job of assessing Steele’s connections with Russian oligarchs, who could have been part of a Russian disinformation plot. Both Priestap and Stuart Evans, a deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s National Security Division, told the inspector general that the government should have more closely scrutinized Steele’s relationship with Russian Oligarch 1. The inspector general concurred with that assessment. In a final analysis, the inspector general wrote:

[W]e believe that more should have been done to examine Steele’s contacts with intermediaries of Russian oligarchs in order to assess those contacts as potential sources of disinformation that could have influenced Steele’s reporting or, at a minimum, influenced Steele’s understanding of events in Russia that furnished context for the analytical judgments he used to evaluate the reporting.

***

Grassley and Johnson are still on the hunt for more information. They recently wrote FBI Director Christopher Wray to request all of the intelligence records reviewed by the Crossfire Hurricane team.

Meanwhile, Attorney General William Barr has given yet another interview in which he has stated that he is “very troubled” by what has been found thus far by U.S. Attorney John Durham’s ongoing probe into the government’s Russia investigation. But Barr has not offered a basis for this assertion, and very little information is available about Durham’s inquiry. Casting further doubt on Barr’s comments, the Republican-led Senate Intelligence Committee found on April 21 that the intelligence community’s assessment that Russia interfered with the 2016 election presented “a coherent and well-constructed intelligence basis for the case of unprecedented Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.” According to the New York Times: “In their report, senators essentially said they had asked the same questions that Mr. Durham is now examining and found that the intelligence agencies’ work stood up.”