Commitment to Balance Is Vitally Important for Successful Implementation of CHMR-AP

Maintaining deliberate balance between divergent approaches is necessary for operationalizing the Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response-Action Plan to optimize joint targeting processes without compromising military effectiveness and national security.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Publication of the Department of Defense Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response-Action Plan (CHMR-AP) at the end of August has prompted an appreciable degree of debate regarding how the plan will be implemented in practice and how best to operationalize civilian protection practices in general. On Lawfare, insightful analysis has been presented by Todd Huntley (article posted days before CHMR-AP publication, but generally addressing content reflected in the policy), Marc Garlasco (article here), and Geoffrey Corn and Peter Margulies (article here)— with additional commentary from Huntley and Garlasco on the Lawfare Podcast. This expert analysis accompanies an equally insightful collection of articles emerging on Articles of War (so far here, here, and here).

Reactions to the content of the action plan generally range from cautious optimism (mostly among civil society advocates) to concern about the potential for degraded operational effectiveness (mostly among current military practitioners). Indeed, the outlooks published to date are fairly consistent with perspectives I have encountered in discussions with friends and colleagues in civil society and military practice about the policy and about civilian harm mitigation practices more broadly.

The common thread emerging from across the range of reactions is that the plan shows promise, but judgments about its merits should be reserved pending an assessment of how it is ultimately executed in practice. If the CHMR-AP isn’t implemented effectively, it risks becoming just another added layer of Defense Department bureaucracy with no discernable practical benefit. If it is allowed to focus too heavily on civilian protection in the effort to “improve” targeting practices, it risks compromising operational effectiveness and, therefore, national security.

At its core, the CHMR-AP is perspective neutral. It essentially establishes a strategic-level structure designed to identify and disseminate best practices to improve targeting outcomes across the Defense Department as an enterprise. The policy is ambitious in scope and detail, which is to be expected since Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin directed the creation of an action plan rather than a conceptual analysis.

It is entirely reasonable to withhold judgment on the effectiveness of the CHMR-AP. If implementation of the plan is analogized to building a barn, then Secretary Austin established a solid foundation in his directive, while the “Tiger Team” that drafted the policy assembled and stood up the frame. How well the rest of the barn is constructed and what functions it serves will take shape in the future—but the foundation and frame are essential first steps.

Based on my experience as a combat arms soldier and officer turned military lawyer turned academic, I am encouraged by the plan and its potential for stimulating and fostering positive change in U.S. military targeting processes. I see many of the latent deficiencies I encountered and sought to correct within my own echelons of practice reflected in current Defense Department practice today.

In the absence of strategic-level guidance and prioritization, identified best practices regarding targeting processes are difficult to sustain, disseminate, and incorporate across the force—especially in an enduring manner. CHMR-AP implementation can fix that, if it’s done right.

Balancing Civilian Protection and Military Practitioner Perspectives in CHMR-AP Implementation

Even with an impressive foundation and frame, it is not a foregone conclusion that the Defense Department will get implementation right by striking the proper balance between enhancing civilian protection practices and maintaining operational effectiveness. Given the potential for positive change and avoidable pitfalls ahead, I share both in the prevailing cautious optimism and perceptible skepticism.

As the organizational structures contemplated in the CHMR-AP are constructed, it is important for outside observers to maintain patience along with the vigilance that is already clearly being demonstrated. The Tiger Team, which consisted of a group of experts from across the Defense Department, developed a genuinely impressive degree of detail to explain how the department can get from a plan that exists only on paper to a fully operational collection of entities that works at all echelons of command, starting at the secretary/chief level all the way to the tactical level.

Bringing the plan from paper to practice, though, starts with identifying and submitting unfunded requests so that the bills can be paid and personnel can be hired and assigned. The work at the outset is decidedly unglamorous, but time, patience, prioritization—and a lot of money—are needed before the organizational structures achieve full operational capability a few years from now.

In the meantime, it is essential that these early steps in the ongoing organizational construction between CHMR-AP publication and reaching full operational capacity years from now are carried out with care and foresight. Balance must be the watchword: balance between civilian protection practices and operational effectiveness. Guidance reflected in the CHMR-AP doesn’t necessarily tip the scales in either direction, but those responsible for swinging the hammer as the structure gets built from here may well do so.

A powerful dynamic that has been simmering just below the surface for years is discord, and indeed at times outright acrimony, between civil society advocates and military practitioners. Despite the mandate frequently expressed by then-Army Judge Advocate General Charles “Chuck” Pede (now a retired lieutenant general) to “flood the zone” of public discourse with strategic legal messaging, that guidance has never been realized. In reality, civil society advocates dominate the forum of public discourse (for but a small sampling, see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). In comparison, perspectives from military practitioners are more akin to a light drizzle than a flood.

A full accounting of the discord between the two general approaches and its practical effect is beyond the scope of this article, but it is useful to acknowledge the simmering conflict underpinning the development and, now, implementation of the CHMR-AP. The prevailing discord accounts for the divergence between the cautious optimism expressed on these pages by Marc Garlasco of PAX and, for example, the concern regarding the potential for degraded operational effectiveness in implementing the CHMR-AP recently articulated on Articles of War by military lawyers Maj. Justin MacDonald and Maj. Ryan McCormick.

Civil society actors for years have been tirelessly advocating for the Defense Department to implement a variety of recommendations developed from a civilian protection perspective. These efforts have been met with some limited success, but by and large, the recommendations are not adopted or implemented in military practice. This reluctance by the military is reasonable and predictable, as the strategic objectives of civil society groups and the Defense Department are generally not aligned.

Recent high-profile media coverage of Defense Department combat operations has caused a rapid and sudden change in strategic direction. Controversy sparked by media coverage created a primary driving force behind the directive to develop the CHMR-AP and the policy itself, although media coverage doesn’t necessarily present a balanced and realistic depiction of accountability standards and practices that apply in actual military practice (a working paper presenting my research and critical analysis of the media coverage is available).

Whatever the virtues of recent high-profile media coverage of military combat operations, there is no question that it has created controversy in public opinion that civil society advocates have exploited effectively. This movement has encouraged increasingly assertive interventions by Congress related to Defense Department targeting and accountability practices as well as Defense Department strategic-level prioritization, including development of the CHMR-AP.

Both legislative intervention and policy-level prioritization present opportunities for civil society advocates to pursue their own reform agendas from inside the government, even though the strategic objectives of advocacy groups do not necessarily align with those of the Defense Department.

For CHMR-AP implementation to be effective going forward, those responsible for charting its initial course from the outset will need to remain sharply aware of, and account for, the discord between the two general approaches. Balance is the watchword, and it must be applied deliberately and vigilantly.

SERVICE Approach to Guide CHMR-AP Implementation at the Outset

While the guidance presented in the CHMR-AP is impressive in detail and scope, as the frame of the proverbial barn the action plan is not designed to provide comprehensive schematics describing how the organizational structures reflected in the policy are supposed to be built. This observation is not intended as a critique of the plan since the goal of the CHMR-AP is to chart the path, at the policy level, toward organizational improvement rather than to provide detailed guidance for how the institutional structures are intended to function once they’re fully operational.

Even so, those details will start to materialize in the months and years ahead while the plan is shepherded from paper to practice. As the plan comes together, however, some degree of concrete guidance will be useful for those who are involved in the process and for observers monitoring progress from the outside.

At the most basic level, the CHMR-AP aims to improve the procedures by which Defense Department personnel conduct joint fires targeting and planning as an enterprise in three areas at which performance within the military has historically been decidedly poor. The first general limitation in existing practice is the process by which the targeting community systematically identifies best practices from lessons learned in targeting operations. The second is standardizing civilian harm mitigation and response processes across theaters and combatant commands when possible in order to optimize unity of effort across the Defense Department. The third general area of institutional improvement the CHMR-AP addresses is implementing best practices at echelon and across the enterprise.

Optimizing targeting procedures in these general areas will be a primary focus, for example, of the Civilian Protection Center of Excellence, which is the flagship organization designated in the CHMR-AP (Objective #2), and the Civilian Harm Assessment Cells, which will be a foundational pillar for civilian harm mitigation practices across the Defense Department (part of Objective #7).

As a coordinating strategy for those involved in establishing the institutional structures created by the CHMR-AP, and those responsible for monitoring the progress, I suggest developing an inventory of specified organizational functions to ensure that the effort of implementing the plan is effectively and efficiently contributing to the desired end state of institutional improvement. This suggested inventory can be abbreviated by the acronym SERVICE, which captures the following organizational functions: synthesize, evaluate, resource, validate, interface, coordinate, and educate.

Here is a summary of how each of these organizational functions can foster and sustain institutional improvement of targeting practices:

- Synthesize information related to targeting operations from all echelons across the Defense Department in expeditionary and domestic settings.

- Evaluate existing doctrine involving civilian protection and targeting procedures to identify areas to be sustained and improved.

- Resource civilian protection and targeting process optimization endeavors at the strategic level and ensure they are adequately resourced at the operational and tactical levels.

- Validate best practices and lessons learned to maximize the effectiveness of civilian protection methods while not unduly compromising mission accomplishment.

- Interface with interagency officials, lawmakers, foreign military and governmental organizations, civil society, and the general public on matters related to civilian protection and targeting process assessment/optimization.

- Coordinate within the Defense Department to assess the effectiveness of current targeting practices to synchronize implementation of best practices and lessons learned across the enterprise.

- Educate individual service members, collective elements at all echelons of command, and foreign security personnel using a systematized and comprehensive plan that incorporates professional military education, existing institutional instructional activities, mobile training teams, home station unit training, and on-site simulations and command post exercises.

The above inventory of functions suggested for the organizational structures that will be created with CHMR-AP implementation nests with guidance presented in the plan and is developed from my own analysis of the policy. While the CHMR-AP is impressive in detail and scope, drawing from a practical inventory of specific organizational functions can help guide implementation as the plan is operationalized.

Recommendations for Operationalizing CHMR-AP Developments Such as the Civilian Protection Center of Excellence and Civilian Harm Assessment Cells

While the suggested SERVICE approach can provide useful guidance for organizational functions, one significant obstacle to successful implementation is developing concrete details to bring the CHMR-AP from a strategic vision to a practical reality. This process will involve a veritable ocean of details, from the grand to the mundane.

While an exhaustive list of these practical considerations is beyond the scope of this article, below is an overview of some of the most important details that will need to be addressed in the near term, along with brief suggestions for how to settle these currently unresolved implementation issues.

Leadership: The flagship Civilian Protection Center of Excellence (CP CoE) should be led by a civilian director and a two-star general officer/flag officer commander. Hiring a civilian director who is not a political appointee will allow for institutional continuity and direct engagement with the civilian secretaries and Congress, and the two-star commander will bring suitably broad maneuver experience while being a rank peer with division commanders and interservice equivalents. The civilian director should be a Senior Executive Service Level 2 appointee with substantial experience with military targeting operations, civilian protection methods, and institutional assessment and development. The initial two-star commanding general should ideally be a post-command Army division commander or service equivalent, since this echelon of command is responsible for integrating joint fires and multiple combined arms maneuver elements in a single battlespace.

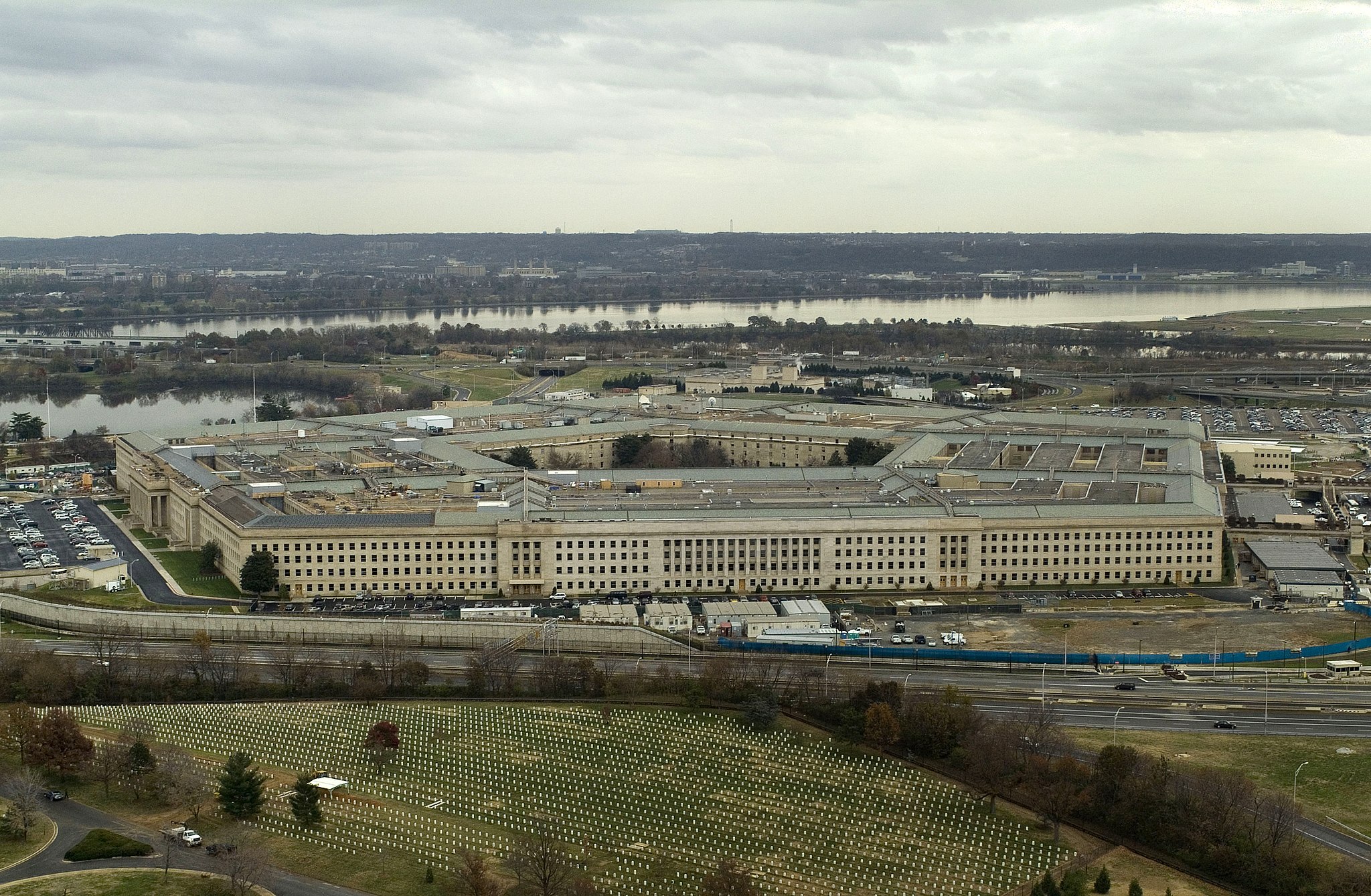

Location: Proximity to the Pentagon, the Hill, and National Defense University (NDU) and other military educational institutions makes Fort McNair in Washington, D.C., an ideal location for the CP CoE. Frequent coordination at the Pentagon with service secretaries, the joint chiefs, and senior personnel in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as well as select lawmakers on Capitol Hill, will be central to the CP CoE mission, and NDU is the institutional hub for several important spokes of professional military education within the department. With these essential aspects of the CP CoE mission in mind, there is perhaps no location better suited as the home of the center than Fort McNair. McNair is a small post and space is limited, but the parking lot across from NDU could be moved underground and the CP CoE could be built above, or there are a few current tenant institutions that are good candidates to be relocated to Fort Belvoir about 20 miles away. As an alternative to McNair, Belvoir might be a feasible location for the CP CoE.

Facilities: The flagship CP CoE should be designed with sufficient facilities to host an Army corps-level command post exercise in support of a robust training function as well as adequate classroom and teaching facilities to support the institutional learning function. It is vital that the CP CoE be designed with a sensitive compartmented information facility (SCIF) capable of managing up to Top Secret /Sensitive Compartmented Information (TS/SCI) material. One common cause of target misidentification incidents is misinterpretation of factual conditions that is introduced when raw intelligence at the TS/SCI level is summarized by intelligence analysts and reduced to the Secret level for use in targeting operations. This will need to be a focal point of CP CoE training and teaching activities as well as reach-back support for forward deployed units. A SCIF rated to TS/SCI will be necessary to facilitate this operational function.

Synchronization: To maximize organizational impact, a deliberate plan will need to be developed for the CP CoE to have a liaison team located with, and under tactical control of, supported military commands and organizations. Examples of supported elements include combat training centers and similar institutions such as the U.S. Army Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center/MAGTF Training Command at Twentynine Palms, California, as well as professional military education institutions. Close collaboration with these institutions will facilitate the flow of information both up to the CP CoE and down to the rest of the force.

Civilian Harm Assessment Cells (CHACs): While implementation of CHACs will create a much-needed feedback loop to complete the targeting cycle by, according to the CHMR-AP, enabling “learning from incidents that result in civilian harm,” units must be adequately resourced to staff CHACs as separate positions rather than assigning CHAC participation as an additional duty for existing targeting personnel. The targeting process is primarily forward-looking, since the main “purpose of joint targeting is to integrate and synchronize fires into joint operations” in order to “create effects in support of [joint force commander] objectives and end state.” The CHAC function of learning from incidents that result in civilian harm, however, is inherently backward-looking—that is, to determine what could be improved to reduce the chances of a similar mishap rather than forward-looking in support of the next iteration (and the next, and so on) of the targeting cycle. According to guidance established in the CHMR-AP, “CHACs will consist of personnel with expertise in intelligence, fires, civil-military relations, post-strike assessments, analyses, and/or language relevant to the area of operations.” These are the right qualification criteria, but positive effects of practical implementation will be negligible if commands are required to assign current personnel to the CHAC because new positions aren’t created on the unit’s Military Table of Organization and Equipment. For the CHAC to successfully perform a robust after-action review and assessment function while not degrading the ability of existing targeting personnel to integrate and synchronize joint fires, creating new positions rather than requiring units to develop CHACs out of hide will be necessary. This will require adequate resourcing and coordination, but the effort and cost will pay dividends in addressing one of the most pernicious and persistent systemic deficiencies in existing joint targeting practices.

The above is not intended to be a comprehensive catalog of the details that will need to be hammered out in the coming months and years as the idea of CHMR-AP becomes a practical reality. This small sampling, though, highlights the copious amounts of time, patience, prioritization, and money that will be required to fully implement the ambitious plan the CHMR-AP establishes.

The CHMR-AP strikes just the right balance by presenting enough details to provide adequate strategic guidance while maintaining flexibility by not being too prescriptive and, perhaps most important of all, remaining sufficiently neutral regarding the prevailing divergence in perspectives and approaches. A solid foundation and a sturdy frame are in place. Now the meticulous and detail-oriented task of building the proverbial barn can get underway. The above represents a tiny fraction of the details that lie ahead, but the institutional dividends that can result from effective CHMR-AP implementation are well worth the effort and cost.

Conclusion

The strategic guidance established in the CHMR-AP sets the conditions for systemic institutional developments that support mission accomplishment by optimizing existing targeting processes while saving lives by mitigating risk to civilians. Cautious optimism (mostly) from civil society advocates is reasonable, as is concern regarding the potential for the erosion of operational effectiveness expressed (mostly) by military practitioners.

If the organizational structures developed from the CHMR-AP guidance prove ineffectual or even detrimental to mission accomplishment, the suboptimal outcome won’t ultimately be attributable directly to the action plan. The CHMR-AP establishes ample raw materials. Whether the plan results in a dud or a masterpiece will be left to those charged with implementing the plan and overseeing implementation.

From plan publication to full operational capability, deliberately maintaining a satisfactory balance between civilian protection and military practitioner perspectives will be vitally important. Understanding and accounting for discord between the two general approaches is a requirement for maintaining balance as a watchword during implementation.

As the CHMR-AP is implemented, the SERVICE approach to organizational functions and the sampling of practical suggestions presented above can help fill in the gaps deliberately left by the plan.

The structure is in place. How the plan is put into action now will determine its ultimate utility. Providing adequate prioritization and resourcing while deliberately fostering balance between divergent perspectives will be of foundational importance in the endeavor to maximize the benefit of CHMR-AP implementation while not compromising operational effectiveness and national security.