Countering the Ransomware Threat: A Whole-of-Government Effort

The United States government has adopted a comprehensive approach to combating ransomware.

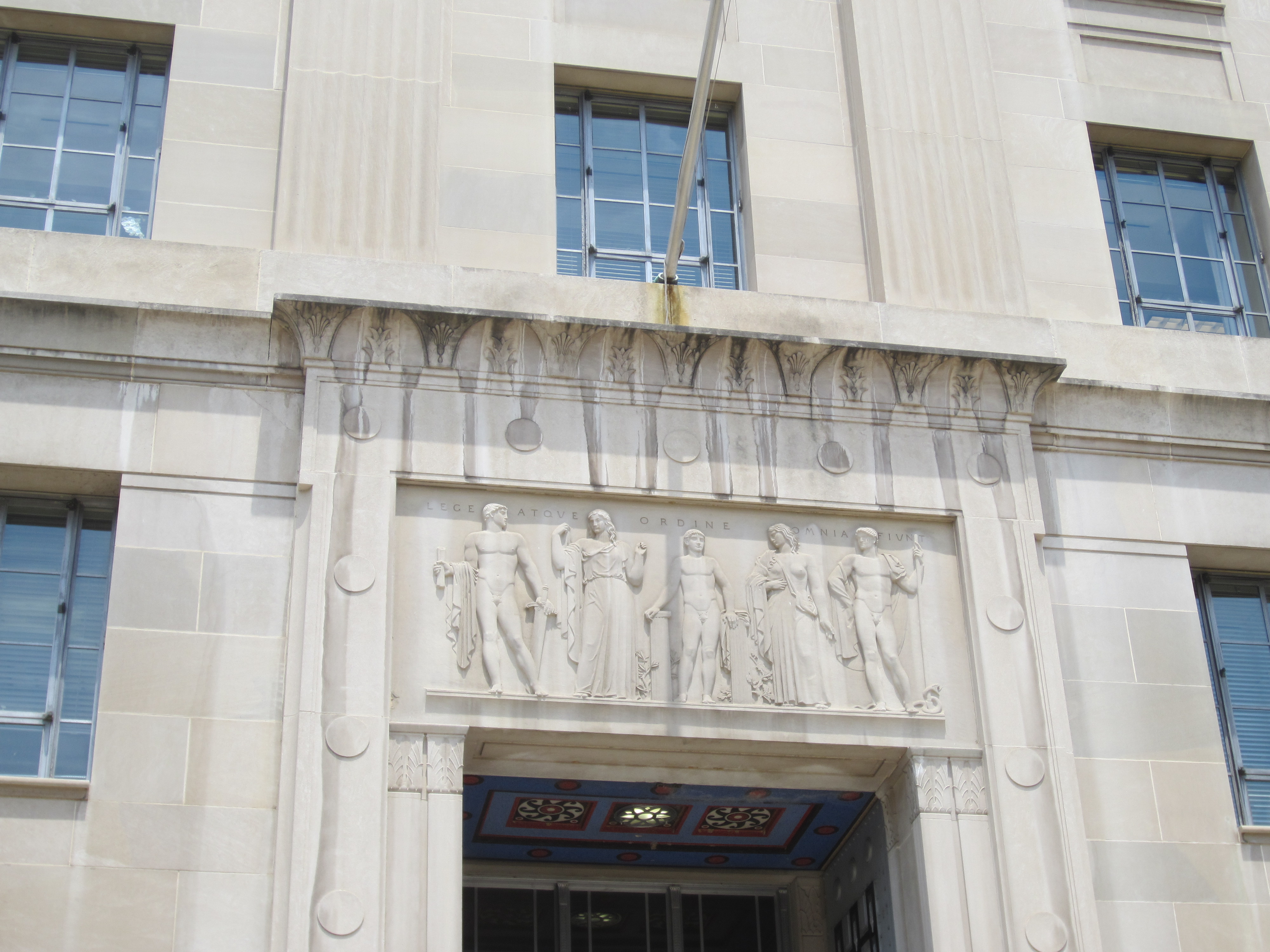

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On Nov. 8, the Justice Department held a press conference, along with the FBI and the Treasury Department, to announce a variety of actions taken against REvil, the ransomware group responsible for the Kaseya and JBS attacks. Those actions included indictments, arrests, the seizure of funds, the designation of a virtual currency exchange and a reward offered to those who provide relevant information about individuals holding leadership positions in REvil.

While ransomware attacks are often perpetrated by criminal gangs seeking to make a profit, digital extortion efforts directed at U.S. critical infrastructure have raised the stakes for both ransomware groups and the U.S., turning what once might have been classified simply as cybercrime into a national security issue. Accordingly, the U.S. government has begun to leverage a range of criminal, diplomatic, economic and military capabilities in order to combat the ongoing ransomware threat.

Based on developments over the past several months, this post will provide an account of how the Biden administration is going about the business of countering the ransomware threat through a whole-of-government approach. This approach includes initiatives and actions by the Justice Department, the Treasury Department, the Department of Homeland Security and other agency-specific efforts. In an effort to begin to assess the efficacy of these activities, this post will also describe the impact such efforts appear to be having on at least some ransomware threat actors, most notably the decision by REvil to take itself “offline” and the ripple effects in the ransomware ecosystem stemming from that action.

A Whole-of-Government/Whole-of-Nation Effort

Over the past six months, the White House has taken diplomatic action, strengthened international partnerships, and engaged in outreach to the private sector, all in an effort to address the expanding cybersecurity threat environment. In June, President Biden met with Russian President Vladimir Putin to discuss the issue of cybercrime. In these talks, Biden made clear that certain critical infrastructure should be off limits to cyberattacks and further reiterated that the United States “would take action to hold cybercriminals accountable.” In August, Biden met with private-sector leaders to discuss and develop a “whole-of-nation-effort” to address, among other issues, how better to secure the technology supply chain. Several meeting participants announced new initiatives as part of this effort—Google will invest $10 billion to expand zero-trust programs, IBM will train 150,000 people in cybersecurity skills and Amazon will make its security awareness training freely available to the public.

In October, the White House held an international summit focused on strengthening efforts to combat ransomware and other cybercrime. The U.S. invited representatives from across the globe, including Brazil, India, Kenya and Singapore. Notably, Russia was not on the guest list. The Counter Ransomware Initiative Meeting concluded with a joint statement that highlighted four areas of focus: improving network resilience; countering illicit finance; disrupting the ransomware ecosystem through increased collaboration among law enforcement, intelligence and agencies, and foreign partners; and leveraging coordinated diplomatic action when states are not taking reasonable steps to stop ransomware attacks emanating from within their borders. More international collaborations are certain to follow, as U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan acknowledged that “no one country, no one group can solve this problem.”

As part of this whole-of-government effort, various government agencies have also taken concrete steps to address the ransomware threat. These agency-specific initiatives and actions are summarized below, with a final section examining how a range of government capabilities were brought to bear against REvil, including public reporting that suggests U.S. Cyber Command was part of an international effort that led REvil to take itself offline.

Department of Justice

The Justice Department is engaging in a series of initiatives and efforts to ensure that all appropriate resources are directed at the ongoing ransomware threat. The department launched the Ransomware and Digital Extortion Task Force, through which it is developing a strategy to target all elements of the ransomware ecosystem. Beyond that, it is also increasing collaboration with the private sector, international partners and other government agencies that bring important capabilities to the disruption mission. In early October, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco also announced the creation of the Civil Cyber-Fraud Initiative and the National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team (NCET).

Through the Civil Cyber-Fraud Initiative, the department plans to leverage the False Claims Act to address cybersecurity-related fraud by government contractors and grant recipients. More specifically, the department will hold individuals or entities liable for “knowingly providing deficient cybersecurity products or services, knowingly misrepresenting their cybersecurity practices or protocols, or knowingly violating obligations to monitor and report cybersecurity incidents and breaches.” The False Claims Act also provides a whistleblower provision that allows private parties to assist the government in identifying and prosecuting fraudulent conduct, which then may entitle them to a portion of the funds recovered by the government.

The purpose of NCET is to deter, disrupt, and prosecute “criminal misuses of cryptocurrency,” with particular attention to cryptocurrency exchanges and other actors involved in facilitating ransomware payments. This team, through leveraging existing expertise from within the Justice Department, is also “assist[ing] in tracing and recovery of assets lost to fraud and extortion, including cryptocurrency payments to ransomware groups.” In May, the Justice Department successfully seized 63.7 bitcoin, currently valued at approximately $2.3 million. These funds allegedly represent the proceeds of a May 8 ransom payment to individuals in a group known as DarkSide, which targeted Colonial Pipeline, resulting in the company shutting down its operations and thus taking U.S. critical infrastructure offline. While the seizure took place before the formation of NCET was officially announced, it is illustrative of the kind of work NCET might undertake.

Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury is also leveraging its existing powers and expertise to combat the widespread ransomware problem. Both the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) have become key players in the whole-of-government effort to counter ransomware.

In June, FinCEN issued the “first government-wide priorities for anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism policy.” These “priorities” and accompanying statements, issued pursuant to the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, reflect the government’s views of the “threat landscape” and include the “acute threats'' of ransomware and other cybercrimes. The priorities will be updated at least once every four years and are intended “to assist covered institutions in their AML/CFT [anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism] efforts and enable those institutions to prioritize the use of their compliance resources.” Although these priorities do not require financial institutions to make immediate changes to their risk-based AML programs, they allow covered entities to begin considering how to reshape their compliance programs before final implementing regulations are promulgated.

In September, OFAC issued its first action against a virtual currency exchange for its role in “facilitating financial transactions for ransomware actors.” OFAC designated the Russian-based cryptocurrency exchange Suex “for providing material support to the threat posed by criminal ransomware actors.” Suex was facilitating transactions involving proceeds from at least eight ransomware variants, and “over 40% of the company’s known transaction history [was] associated with illicit actors.” In making this first-of-its-kind designation, the Treasury Department noted that “[v]irtual currency exchanges such as S[uex]are critical to the profitability of ransomware attacks, which help fund additional cybercriminal activity.” The OFAC designation means that transactions in “all property and interests in property [of Suex] ... subject to U.S. jurisdiction are blocked” and that U.S. persons who engage in such generally prohibited transactions with Suex risk exposure to sanctions or enforcement actions.

In October, OFAC released its updated guidance on sanctions compliance for the virtual currency industry. Transactions involving virtual currencies, like those involving traditional fiat currencies, are subject to OFAC compliance obligations. The guidance overview acknowledges the growing role that virtual currencies will play in the global economy and the corresponding exposure to sanctions risks that virtual currencies present, “like the risk that a sanctioned person or a person in a jurisdiction subject to sanctions might be involved in a virtual currency transaction.” Accordingly, the guidance provides a summary of the relevant sanctions requirements, best compliance practices and other resources aimed at helping exchanges mitigate these risks. The guidance, for example, includes advice on how to bolster internal controls like geolocation and blocking tools to ensure individuals from sanctioned jurisdictions cannot access a virtual currency exchange or its related services.

In October, FinCEN also released a financial trend analysis report entitled Ransomware Trends in the Bank Secrecy Act Data Between January 2021 and June 2021. The analysis illustrates what appears to be a tremendous increase in the amount of money flagged by U.S. financial institutions through suspicious activity reports (SARs) as suspected ransomware-related payments to cybercriminals: $590 million in the first six months of 2021, as compared to $416 million for all of 2020. Under the Bank Secrecy Act, financial institutions must report suspicious activity that might signal criminal activity by filing a SAR no later than 30 calendar days after initial detection of the relevant activity. This increase suggests that financial institutions are detecting rising amounts of money being paid as ransom, which underscores the need for legislation to require timely reporting of ransomware attacks to the government by victims so that harms to victims can be mitigated and information can be shared expeditiously to prevent further ransomware infections. As a recent memorandum on ransomware from the majority committee staff of the House Committee on Oversight and Reform observes, however, timely reporting can happen only when there are “clearly established federal points of contact in response to ransomware attacks.”

Department of Homeland Security

Following the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack, the Department of Homeland Security has worked to strengthen cybersecurity for critical infrastructure through Transportation Security Administration (TSA) security directives. In May, TSA announced a security directive for critical pipeline owners and operators to designate a cybersecurity coordinator who must be available 24/7, conduct a comprehensive review of their current cybersecurity, and report any incidents to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). In July, TSA issued another security directive that:

requires owners and operators of TSA-designated critical pipelines to implement specific mitigation measures to protect against ransomware attacks and other known threats to information technology and operational technology systems, develop and implement a cybersecurity contingency and recovery plan, and conduct a cybersecurity architecture design review.

Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas also announced that TSA will issue additional regulations to strengthen the cybersecurity of U.S. railroads, rail transit and the aviation sector. These regulations will include similar requirements from past directives, such as the appointment of a cybersecurity coordinator and the establishment of a contingency plan in event of an attack. Moreover, Mayorkas indicated that TSA will look into other relevant industries and issue guidance for “lower risk entities” to aid them in improving their cybersecurity.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency is also playing an important role in helping U.S. entities protect themselves from ransomware attacks. In September, CISA issued a Ransomware Guide covering best practices for preventing ransomware attacks and a ransomware attack checklist to assist victim organizations that must respond to ransomware attacks. The guidance was developed from “operational insight” and is directed toward “information technology (IT) professionals ... [and] others within an organization involved in developing cyber incident response policies and procedures or coordinating cyber incident response.” CISA, through the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT), also offers entities the opportunity to submit malware for analysis and warnings about threats to systems, along with guidance about available mitigation strategies.

The Whole-of-Government Crackdown on REvil

The Nov. 8 press conference brought into sharp focus the administration’s ongoing efforts to counter the ransomware threat. The Justice Department announced indictments against two foreign nationals—both associated with the ransomware group REvil—for their role in “conducting ransomware attacks against multiple victims.” The conduct covered by the indictments includes the July 2021 attack against Kaseya and attacks “on business and government entities in Texas on or about Aug. 16, 2019.” The department was also able to seize $6.1 million in funds allegedly traced to ransomware payments received by one of the defendants.

In conjunction with these events, the Treasury Department announced OFAC’s designation of Chatex, a virtual currency exchange that has “facilitated transactions for multiple ransomware variants.” According to the Treasury Department, Chatex has “direct ties” to the previously sanctioned Suex virtual currency exchange and was designated specifically for “providing material support to Suex and the threat posed by criminal ransomware actors.” OFAC also designated the two defendants named in the indictments for their role in “perpetuating Sodinokibi/REvil ransomware incidents against the United States.” As a culminating illustration of U.S. whole-of-government efforts to combat ransomware, the Department of State announced a reward of up to $10 million for “information leading to the identification or location of any individual(s) who hold a key leadership position in the Sodinokibi/REvil ransomware variant transnational organized crime group.”

Prior to all of these events, however, REvil was already experiencing difficulties with its own operations, ultimately causing it to “go offline.” The U.S. government has not officially commented on any offensive cyber operations directed against REvil’s servers, but public reporting suggests that REvil’s troubles began over the summer when a U.S. foreign partner hacked into the group’s servers. This compromise, in turn, allowed the FBI to gain access to REvil’s servers and private keys, which, according to the Washington Post, the bureau shared with U.S. Cyber Command. REvil did take itself offline following the July Kaseya attack, but that decision was seemingly unrelated to the hack by the U.S. foreign partner, which apparently continued to escape REvil’s notice for some time. When REvil came back online in September, Cyber Command—with the private keys in hand—apparently launched a “disruption effort” against a Tor site REvil used in its extortion efforts, which led REvil to discover the original breach that occurred over the summer. With that discovery, the group, once again, took itself offline. Following detection of the original compromise, a REvil operator wrote a parting message: “Good luck everyone, I’m off.”

REVil’s departure, following its disclosure that it had been compromised, also produced certain ripple effects within the ransomware ecosystem. Hours after REvil went offline, DarkSide ransomware operators began moving its bitcoin funds in an attempt to launder nearly $7 million worth of bitcoin. DarkSide is the ransomware group responsible for the Colonial Pipeline attack and other malicious intrusions, from which it has collected nearly $90 million in ransom from its victims.

Two other ransomware groups also reacted to REvil’s departure with angry public statements directed at the U.S. The Groove ransomware gang published a blog on a Russian site calling on all other ransomware groups to target the United States and its interests in retaliation for its actions against REvil. Notably, the blog post made clear that Chinese companies should not be targeted, as China may become a “safe haven” in the event Russia takes a stronger stance against cybercrime operations emanating from within its borders. The Conti ransomware group also released a statement in which it called the United States the “biggest ransomware group of all time” and questioned the legal authority of the REvil operation.

What should policymakers and the public make of all this activity? It’s probably too early to draw conclusions, although there may be some early lessons to learn. However, it is clear that the U.S. government is leveraging its resources and directing significant capabilities toward combating the ransomware threat. While the current whole-of-government approach has produced some “wins” in recent months, more time is needed to assess whether these efforts will have a sustained effect in preventing ransomware attacks generally and in forcing REvil to stay offline.

.png?sfvrsn=aed44e61_5)