Daniel Webster, War Powers and Bird$h*t

In the course of researching a book, I’ve come across many episodes that Benjamin Wittes and I like to call “Weird War Powers $h*t.” One of my favorites is a story about American constitutional war powers and actual $h*t. It’s a story about very expensive bird-$h*t, or guano, and how one of the 19th century’s most important thinkers on war powers nearly stumbled the nation, figuratively speaking, into a giant pile of it.

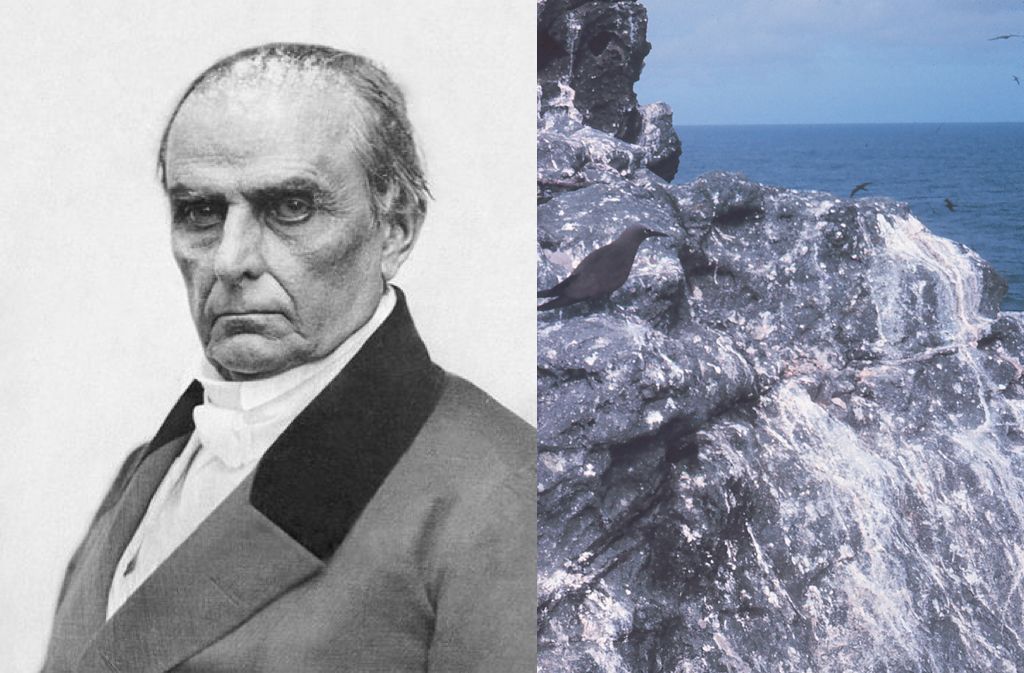

Daniel Webster and War Powers

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In the course of researching a book, I’ve come across many episodes that Benjamin Wittes and I like to call “Weird War Powers $h*t.” One of my favorites is a story about American constitutional war powers and actual $h*t. It’s a story about very expensive bird-$h*t, or guano, and how one of the 19th century’s most important thinkers on war powers nearly stumbled the nation, figuratively speaking, into a giant pile of it.

Daniel Webster and War Powers

Daniel Webster was one of the 19th century’s greatest lawyers, legislators, orators and diplomats, including serving in the House and the Senate and twice as secretary of state. Throughout his service in both political branches, he staked out strong positions that only Congress constitutionally may take the country to war. As a senator in the mid-1830s, he even opposed as unconstitutional a bill to grant President Andrew Jackson the option to engage in military reprisals against French property and to grant Jackson funds to spend, at his discretion, on military defenses, arguing that these were impermissibly open-ended delegations of Congress’s war-making powers. In the Mexican-American War, Webster railed against President James Polk for waging unconstitutional war, alleging that Polk manufactured a military crisis and obtained Congress’s war declaration deceitfully. Besides the usual argument for procedurally constipating war initiation, Webster argued that, in conflict, Congress ought to exercise control over war aims.

Later as secretary of state (1841-1843 and 1850-1852), Webster maintained his position of congressional primacy on going to war. However, as the nation’s top diplomat, he also believed that the president had expansive powers over American foreign policy and responsibilities to protect American interests and citizens abroad, and he viewed gunboat diplomacy as an important tool. The strategic demands of territorial and commercial expansion during his service in the John Tyler and Millard Fillmore administrations therefore created line-drawing problems. A recurring challenge was how to project military power, including threats of force that might escalate or set the United States on a path toward conflict, without stepping over the boundary of Congress’s exclusive war powers.

For example, in 1840, Secretary Webster supported military reprisals against Uruguay in response to its government’s alleged detention and torture of an American national. President Tyler asked Webster if such a move “would be equivalent to a declaration of war [against] a civilized Nation which is exclusively [e]ntrusted to Congress,” whereupon Webster then dialed back the Navy instructions instead to an information-gathering mission. In 1851, the Fillmore administration participated with Britain and France in joint military pressure against Haiti, but Webster was careful to instruct American and foreign diplomats that U.S. naval forces could not engage in direct military action or blockades “without authority from Congress.” That same year, Webster wrestled with how to deter European powers, chiefly France, from interfering with Hawaii’s independence while recognizing that U.S. forces could not take military action to defend Hawaii without congressional authorization. You are unlikely to read about any of these incidents in historical accounts of war powers, because none of them actually resulted in wars—though any of them could have. (Meanwhile, neither Webster nor the presidents he served seemed troubled, as a constitutional matter, by demonstrative military strikes against “uncivilized” entities—nonstate actors or governments not recognized as full, sovereign states—without congressional authorization).

Besides grappling with the scope of presidential power to threaten military force, Webster further believed that strong executive diplomatic powers were needed to keep the United States out of wars. Most famously, he played a critical role in resolving the U.S.-British dispute in the early 1840s over Canadian border clashes and the British militia’s December 1839 destruction of the American steamboat Caroline. In that crisis, which could have provoked war, Webster was especially concerned that private American citizens or state government institutions sympathetic to Canadian rebels might drag the United States into war.

Private individuals dragging the United States into war is what almost happened in the 1852 Lobos Islands guano affair, and Webster’s uncharacteristic sloppiness contributed to the near-debacle.

Guano and the Lobos Islands

Near the end of Webster’s tenure as Fillmore’s secretary of state, in June 1852, a group of American entrepreneurs approached him seeking U.S. government support to take hundreds of thousands of tons of accumulated poop from the barren Lobos Islands off the coast of Peru. That nitrogen-rich turd made ideal fertilizer, which was in short supply for U.S. agriculture at the time. Testifying to its importance in the U.S. economy and to American-Peruvian relations in that era, Fillmore declared in his first annual message to Congress:

Peruvian guano has become so desirable an article to the agricultural interest of the United States that it is the duty of the Government to employ all the means properly in its power for the purpose of causing that article to be imported into the country at a reasonable price. Nothing will be omitted on my part toward accomplishing this desirable end.

Peru guarded jealously its virtual monopoly on the world’s best guano, though, and rebuffed American efforts to secure cheaper imports of it.

When the American entrepreneurs inquired of Secretary Webster whether they could extract guano from the Lobos Islands, their letter described those islands as “uninhabited and unoccupied” and made no mention of Peru’s claims to them. Apparently ignorant of Peru’s historical activities on the Lobos, Webster responded with a letter stating that, unlike other dung-rich islands lying within Peru’s territorial waters, the Lobos Islands were probably discovered by an American mariner and open to exploitation. “Under these circumstances,” Webster continued, “it may be considered the duty of this government to protect citizens of the United States who may visit the Lobos Islands for the purpose of obtaining guano…. I shall consequently communicate a copy of this letter to the Secretary of the Navy and suggest that a vessel of war be ordered to repair to the Lobos Islands....” The Navy secretary in turn so ordered.

As the late Webster-historian Kenneth Shewmaker put it: “Acting on the assumption that the U.S. government had a duty to deploy naval forces to protect American nations and their property when they were in engaged in lawful commerce, Webster had unwittingly taken the first step down a road that nearly led to war.” (See here for Shewmaker’s detailed account of the whole episode.) Based on assurances from Webster and the Navy secretary, the American importers commissioned—and armed—dozens of ships for the mission.

As the flotilla readied to embark, word of it splattered across newspapers and Webster’s promise of American naval protection quickly reached the Peruvian government, which did, in fact, claim long-standing title to the Lobos Islands, with a history dating back to the Incas. Peru protested the American position as contrary to international law and warned that it would resist militarily the plans that it viewed as aggression. The two governments traded diplomatic protests, while accumulating evidence favoring Peru’s position dropped on Webster’s desk. Meanwhile, though, the American businessmen showed no inclination to back off, signaling instead their intention to proceed despite Peruvian threats of armed clashed, and the stench of war clouds wafted up to Washington.

It was on this day—August 21—in 1852, as the fleet of American speculators was en route to the Lobos Islands that Webster wrote three remarkable letters. To the chief American businessman contracting the expedition and who had approached him in the first place, Webster now stated that any use of force against the Peruvian government “would be an act of private war, which can never receive any countenance from this Government.” Additionally, “[t]he naval Commander of the United States in the Pacific will also, under existing circumstances, be directed to abstain from protecting any vessels of the United States which may visit these Islands for the purposes [of extracting guano].” Webster then scolded the businessman for misleading him.

To a friend, Webster privately bemoaned that “[a]ll my concerns in this Department have never given me so much disturbance, as this Lobos business.” He also told him he was submitting correspondence on the matter to Congress (and as I recently explained here, a common form of congressional oversight of incidents like this at that time involved requests for copies of instructions to naval commanders).

Finally, to Peru’s chargé in Washington, Webster wrote that day a lengthy memorandum making a case for Americans’ right of access to the Lobos and its guano. Refusing to concede, Webster continued to lawyer the merits in elaborate detail, but he informed the Peruvian government that military orders to protect the American convoy had been rescinded.

Messages traveled slowly at the time—it could have taken weeks for diplomatic and military instructions to round Cape Horn and reach recipients on the west coast of South America—so at this point the Fillmore administration in Washington had to wait and pray that unintended war was avoided.

A Near Miss and War Powers

A month later, his health severely deteriorating, Webster wrote a private letter to Fillmore on the still-brewing Lobos Islands affair, noting resignedly that at this point “we … must trust to fortune.” Webster accepted responsibility for his hasty blunder in promising military protection without adequate understanding of the facts, and in an especially classy move he offered: “[I]f, in your fortunes hereafter, it shall become necessary to say, that the Lobos proceeding was mine, say so, & use this letter as my acknowledgment of the truth.”

Fillmore responded graciously a few days later. “[L]et us hope for the best[,]” he wrote, knowing that “there is im[m]inent danger of a collision, and it will be almost a miracle if the orders to our fleet countermanding those issued in June should reach Commodore McCauley in time to prevent it….”

In October, Webster passed away. Thanks partly to sheer luck and partly to deft diplomacy by the American minister in Peru to calm the Peruvian government’s nerves and negotiate some limited commercial access to the Lobos guano, military conflict was averted. The Fillmore administration at that point formally acknowledged Peru’s Lobos claims.

Although Webster had eventually reversed his instructions to protect the American guano-extractors, the case illustrates the practical line-drawing issues for his views of war powers at a time when the United States sought to protect its expanding overseas interests. If the Fillmore administration had been more confident of its international legal claims, it probably would have backed up Webster’s assurances of protection. Peru was much weaker militarily, but it was also resolved to protect its valuable and cherished rights. The military situation was, therefore, quite combustible.

Successive administrations of this era viewed convincing displays of naval power as important to deterring attacks on Americans and their property, but doing so also risked escalation. As I discussed recently in the context of another episode from this time, the bombardment of Greytown, there were practical, political and legal obstacles to seeking advance military force authorization from a slow-moving Congress in managing fast-moving foreign crises. Given that, as well as the blurry constitutional zone between executive powers to brandish force and congressional powers to make war, it is no surprise that over time lines would erode in favor of executive unilateralism.