Facebook Takes a Step Forward on Deepfakes—And Stumbles

The good news is that Facebook is finally taking action against deepfakes. The bad news is that the platform’s new policy does not go far enough.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

The good news is that Facebook is finally taking action against deepfakes. The bad news is that the platform’s new policy does not go far enough.

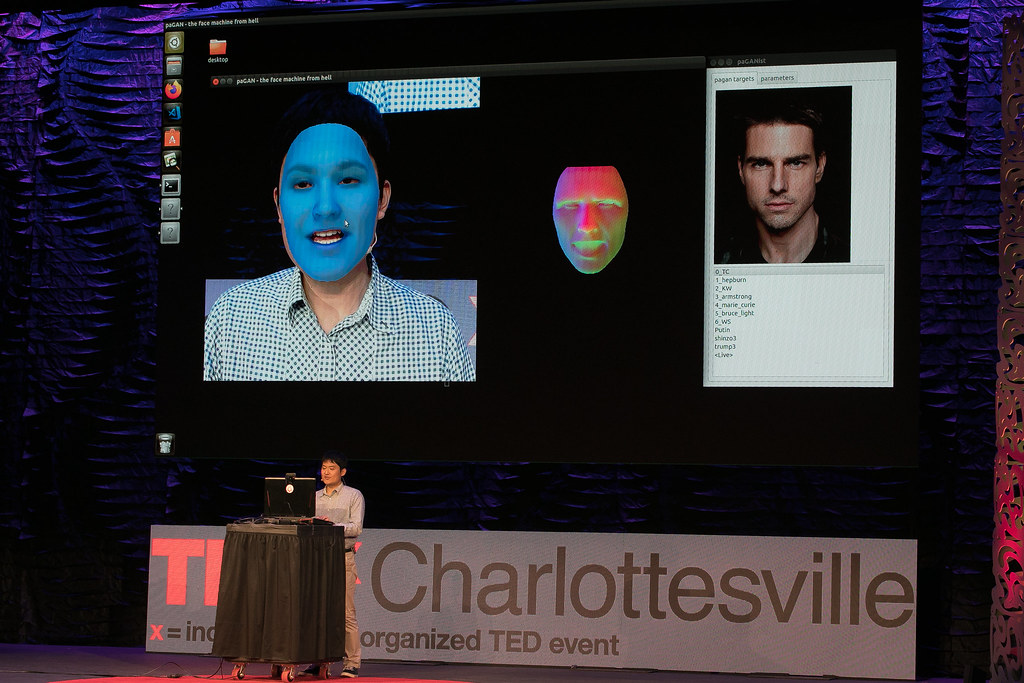

Journalists, technologists and academics have warned in recent years about the potential threat posed by these realistic-looking video or audio falsehoods, which show real people doing or saying things they never did or said. Generated through neural-network methods that are capable of achieving remarkably lifelike results, deepfakes present a challenge for both privacy (the vast majority of deepfake videos are nonconsensual pornography, showing people performing sex acts they never engaged in) and security (consider, for example, the effects of a deepfake showing the president announcing a nuclear strike on North Korea). And as two of us (Citron and Chesney) have written, if deepfakes grow more common, they also “threaten to erode the trust necessary for democracy to function effectively[.]”

So it should have been a relief when, on Jan. 7, Facebook announced a new policy banning deepfakes from its platform. In a blog post on the company’s website, Vice President of Global Policy Management Monika Bickert wrote that Facebook will, going forward, remove the following material from its platform:

It has been edited or synthesized—beyond adjustments for clarity or quality— in ways that aren’t apparent to an average person and would likely mislead someone into thinking that a subject of the video said words that they did not actually say. And:

It is the product of artificial intelligence or machine learning that merges, replaces or superimposes content onto a video, making it appear to be authentic.

This policy does not extend to content that is parody or satire, or video that has been edited solely to omit or change the order of words.

Yet, instead of cheers, the company faced widespread dismay—even anger. The campaign of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, who was recently targeted by a misleadingly edited video in which he appeared to make a racist comment during a campaign speech, declared that Facebook’s announcement represented only the “illusion of progress.” Also angry was the team of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, who was similarly targeted in May 2019 with a deceptively edited video altered to make her appear drunk or in poor health—which Facebook refused to take down at the time. “Pelosi’s people,” wrote Washington Post technology reporter Tony Romm, “are pissed[.]”

So what went wrong?

Before tackling the problems, it’s worth taking a moment to consider what Facebook has done right. It’s a welcome development for the company to endeavor to adopt clear and transparent policies around harmful digital impersonations. Even better is that Facebook is adopting a clear prohibition on certain harmful digital impersonations while carving out important exceptions for satire and parody—without which the policy could risk straying into the silencing of valuable expression.

We applaud Facebook for taking this issue seriously rather than paying it lip service. This is not nothing, nor is it an easy step to take for a company whose business model derives from user engagement with content. Banning certain deepfakes isn’t necessarily good for the bottom line, after all. Deepfakes can attract eyeballs because they involve video and audio, which grabs users’ attention, all the more so when the content is novel and especially if it is negative or salacious. Facebook’s policy shift thus is probably not best understood as naked self-interest but, rather, as a genuine desire to stem harm. Of course, the company also would not mind forestalling heavy-handed statutory or regulatory intervention. But Facebook could have dragged its feet for far longer, at least long enough to enjoy the advertising revenue of viral deepfakes connected to the pending political campaigns as the 2020 election draws closer.

But the newly announced policy falls unfortunately short of what it could have been.

First, Facebook is banning manipulated audio and video showing people saying something they did not say that would deceive the average viewer that the person did say such things (again, exempting satire and parody). It does not, however, cover digital manipulations or fabrications showing people doing things they never did. To be sure, content that does not fall within the ban would still be subject to review by third-party fact-checkers, who would make a determination about deception. If deemed misleading, the content would then be marked as false and downgraded in the newsfeed algorithm. But barring some other violation of Facebook’s rules, it would still circulate no matter how deceptive, significant or harmful.

This is the same procedure Facebook used for dealing with the deceptive video of Pelosi in 2019. But as we wrote then: “Some people will watch flagged content precisely because of the controversy.... Some will distrust the fact-checkers or Facebook itself. Others will not click through to see what, in particular, the fact-checkers thought about it.”

Facebook’s narrow definition of deepfakes is particularly puzzling because it isn’t just faked expressions that can wreak havoc. Thankfully, this doesn’t apply to deepfake pornography, which would already be banned under Facebook’s antinudity policy. But imagine a digital impersonation showing someone stealing something they never set foot near or destroying a valuable item they never touched—or perhaps of a political figure making a rude or offensive gesture. In 2018, a doctored video of gun control activist Emma Gonzalez went viral, showing her appearing to rip up the Constitution. (In the original, authentic clip, Gonzalez tore a paper target in two.) The video was short—just a few seconds—and glitchy. Yet it set off days of outrage among right-wing internet circles. Now consider what a higher-quality deepfake video showing such action could do.

Second, and more troubling from the perspective of our political moment, the new policy apparently would not extend to “cheapfakes” (that is, lower-tech methods used to edit video or audio in misleading ways). The Biden and Pelosi videos, which were produced using regular video editing technology, fall into this category. Cheapfakes, at the moment, are arguably more dangerous than deepfakes in spreading disinformation: They’re simply easier to produce, and, as a result, there are more of them. (Bickert’s announcement notes that deepfakes remain “rare.”) What’s more, the deceptive edits of Biden and Pelosi show that video editing doesn’t need to be a sophisticated deepfake to have an impact. If deepfakes in some cases warrant outright removal, surely so too do cheapfakes.

It’s also not clear how Facebook is going to distinguish between deepfakes and cheapfakes. The new policy defines a deepfake as involving “artificial intelligence or machine learning that merges, replaces or superimposes content onto a video, making it appear to be authentic.” But Facebook hasn’t indicated how it’s going to distinguish between videos edited using artificial intelligence and videos using less sophisticated technology, or where it draws that line. Whatever method the company uses to divide deepfakes from cheapfakes, it will have to grapple with difficult judgment calls on that question alone.

Perhaps there is some kind of a benefit to identifying deepfakes as presumptively more-suspect than cheapfakes in limiting the spread of falsehoods. But there is a danger in treating only deepfakes as the problem and thus failing to adequately address more quotidian types of disinformation.

That leaves the question: What is Facebook actually trying to achieve here? If the goal is to limit the harm of misleading artificial video and audio in an election year, the policy is too narrow. In fact, it’s too narrow even if the idea is to limit the spread of deepfakes alone. Imagine, for example, a deepfaked video of Biden grabbing a woman in an obscene way or giving the middle finger to the American flag. Perhaps a ban on certain deepfakes might be effective in halting the distribution of nonconsensual pornography produced with machine learning or artificial intelligence—but, as noted, this material is already banned from the platform anyway.

Of course, it’s easy to be critical of platforms tackling genuinely difficult content moderation questions. And Facebook’s rollout itself has been plagued with problems unrelated to the policy’s substance, including an apparent misstatement by a company spokesman over whether the platform will permit deepfakes in political advertisements and an unfortunately timed New York Times report on recent incendiary comments by Facebook executive Andrew Bosworth. It is, as we say, encouraging to see Facebook taking the potential danger of manipulated video and audio seriously. It’s just not clear why the company stopped where it did.

.jpg?sfvrsn=b3d4eb92_7)