Flynn Redux: What Those FBI Documents Really Show

A lot of people seem to be expecting Michael Flynn's sudden vindication. They should take a deep breath.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

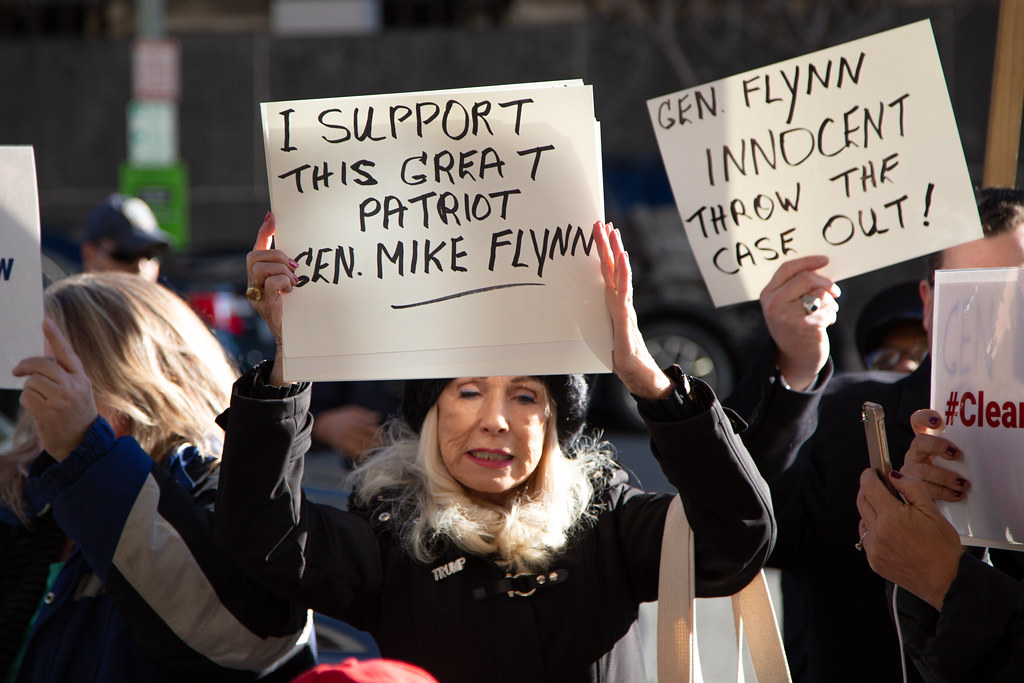

Over the past few days, the president’s supporters have taken a brief break from COVID-19, the economic collapse and the 2020 presidential campaign to fixate anew on the case of General Michael Flynn.

You remember Mike Flynn—the former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency who set a land-speed record for time between appointment as national security adviser and scandal-induced resignation.

Why the sudden interest in the Golden Oldies of the Trump scandals? The reason is the release of some documents from inside the FBI dealing with Flynn’s original interview by agents from the bureau, back from the period when the Trump administration was just coming into power. Flynn’s sentencing on his guilty plea for lying in that interview has been serially delayed. According to some commentators, the documents supposedly show that he was somehow set up, framed or entrapped. A lot of people seem to be expecting his sudden vindication. And a lot more people, some of whom should know better, seem remarkably credulous of Flynn’s new claims.

They should take a deep breath.

The president may well pardon Flynn, as he has long hinted. It’s possible—though for reasons we’ll explain, we think unlikely—that Judge Emmet G. Sullivan will allow Flynn to withdraw his plea. And it’s possible as well that Attorney General William Barr, who has already intervened in the case once before and has asked a U.S. attorney to review its handling, will intervene once again on Flynn’s behalf.

So far, however, nothing has emerged that remotely clears Flynn; nothing has emerged that would require Sullivan to allow him to withdraw his plea; and nothing has emerged that would justify the Justice Department’s backing off of the case—or prosecuting it aggressively if Flynn were somehow allowed out of the very generous deal Special Counsel Robert Mueller cut him.

We have put together this post in an effort to cut through a lot of the disinformation floating around about the Flynn case. We proceed in several distinct steps. First, we offer a procedural history of the case’s recent machinations—how we got to where we are, what the parties are fighting about and how these documents came to be public. Next, we examine the applicable law that governs the matters at issue. We then turn to what’s in the documents and how they interact with the legal standards. Finally, we offer some thoughts and analysis of where things are likely to go from here.

Sentencing Flynterrupted

Flynn pleaded guilty to lying to federal investigators in December 2017. By December of the next year, the government was ready to go forward with sentencing, as Flynn had completed his cooperation with the special counsel’s office. But Flynn still hasn’t been sentenced.

The story is a long one—but the main reason is that in June 2019, Flynn fired his longtime lawyers from Covington & Burling, who had seen him through his guilty plea in November 2017. Instead, he hired Sidney Powell—a lawyer who had been sharply critical of the Mueller investigation—and proceeded to back away from his plea and subsequent affirmation of wrongdoing before the judge, with Powell arguing that Flynn had been “ambush[ed]” by FBI agents aiming to “trap ... him into making statements they could allege as false.” In January 2020, Powell filed two motions directly attacking the case against Flynn: a motion to dismiss her client’s prosecution “for egregious government misconduct,” and a motion to withdraw his guilty plea.

The government responded to Powell’s first motion by arguing that the actions alleged by Powell—including errors made by the Justice Department and FBI concerning the Carter Page Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act applications, as documented by the Justice Department inspector general—do not amount to the “egregious government misconduct” necessary to dismiss the case. In order to respond to the second motion, the government requested access to documents from Covington concerning Flynn’s case: Powell asserts that Flynn should be able to withdraw his plea because he was not adequately represented by his legal team during the negotiation process, and the government wants the relevant material from Covington in order to evaluate Flynn’s claim. Flynn waived his attorney-client privilege with his Covington team with respect to his ineffective assistance of counsel claims, which are predicated on alleged conflicts on the part of the firm.

On the order of Judge Sullivan, Covington began producing documents to the government—essentially, sharing with the government material that it had already provided to Powell when it handed off Flynn’s representation. As part of the firm’s review, it discovered “emails and two pages of handwritten notes” concerning Flynn’s case that mistakenly had not been shared with Powell when Covington had transferred its case file to her after the change in Flynn’s representation. Covington informed the court of its discovery of the materials on April 9 and passed them to Powell.

(Two weeks later, on April 28, the firm notified the court that it had discovered roughly 6,800 additional documents and emails that had not been transferred to Powell. For comparison, by its own estimation, Covington provided about 663,000 documents to Powell when the materials were first handed off. Sullivan has since ordered the firm to review its entire case file to make sure there are no lingering materials that have yet to be provided to Flynn’s new defense team. This second batch of additional material is not important for the rest of the story we’re about to tell, but it’s useful context. Notably, presumably because of the need to review the documents provided by Covington, the government has not yet filed a reply to Powell’s motion to withdraw her client’s guilty plea.)

Meanwhile, Powell was about to receive another tranche of documents from a different source: Jeffrey B. Jensen, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri. In January 2020, Attorney General Barr appointed Jensen to review Flynn’s prosecution—an unusual move in line with Barr’s appointment of Connecticut U.S. Attorney John Durham to conduct a similar review of the Russia investigation as a whole. Many commentators, ourselves among them, have criticized Durham’s probe as an apparent effort by Barr to cast the legitimacy of the Mueller investigation into doubt, and Jensen’s review is open to similar criticism as part of the same effort.

On April 24, the government filed a letter with the court announcing Jensen’s review and indicating that he was sharing unspecified, sealed documents with Powell “as a result of this ongoing review.” That same day, Powell filed a supplement to her motion to dismiss for government misconduct, pointing to two sets of documents: one set of emails from the Covington production, and one document, under seal, from Jensen. Powell wrote that the Covington emails show “misconduct” by Brandon Van Grack, the lead prosecutor handling Flynn’s case, and that the material from Jensen “prove[d] Mr. Flynn’s allegations of having been deliberately set up and framed by corrupt agents at the top of the FBI.”

Five days later, on Sullivan’s orders and without the government’s objection, the Jensen document—containing a handful of emails and a page of notes from FBI officials about the investigation into Flynn—was filed on the public docket. This is what caused the first burst of renewed interest in the Flynn case among the president’s supporters in recent days.

Also on April 29, the government filed another letter indicating that Jensen had passed more material to Flynn’s team. Powell followed the same playbook as last time, filing a supplement to her motion to dismiss for government misconduct and attaching redacted copies of the documents shared with her by Jensen. This material contains further correspondence within the FBI about Flynn’s case.

Flynnterpreting the Actual Law

At least in court—the domain in which he is apparently fighting—Flynn’s argument turns on two bodies of law. His claim that the entire case should be dismissed because of “outrageous government conduct” stems from a 1973 Supreme Court case, U.S. v. Russell, which held out the possibility that a court “may some day be presented with a situation in which the conduct of law enforcement agents is so outrageous that due process principles would absolutely bar the government from invoking judicial processes to obtain a conviction.”

The Justice Department summarizes the defense as follows in the Criminal Resource Manual:

The Supreme Court has never held that the government's mere use of undercover agents or informants, or the use of deception by them, gives rise to a due process violation, although in Russell it left open that possibility. The requisite level of outrageousness could be reached only where government conduct is so fundamentally unfair as to be "shocking to the universal sense of justice." Id. at 432. No court of appeals has held that a predisposed defendant may establish a due process violation simply because he purportedly was induced to commit the crime by an undercover agent or informant. See, e.g., United States v. Pedraza, 27 F.3d 1515, 1521 (10th Cir.) (not outrageous for government "to infiltrate an ongoing criminal enterprise, or to induce a defendant to repeat, continue, or even expand criminal activity."), cert. denied, 115 S. Ct. 347 (1994).

Notably, the Supreme Court, in positing the defense in Russell, denied that it precluded prosecution in a situation in which agents had literally given the defendant hard-to-obtain ingredients for illegal drugs. And as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit put it in 1992, “The stringent nature of the test is demonstrated by the fact that although the defense has been raised many times, in only a small handful of those cases has the government's conduct actually been held to be outrageous.” The successful invocation of the defense has generally involved, the Tenth Circuit explained, either substantial government participation in the criminal activity or significant government coercion in inducing the criminal behavior in the first place. For reasons we explain below, the current record gives Flynn no plausible grounds to prevail on a claim of outrageous government conduct.

The second body of law—the one concerning Flynn’s request to withdraw his plea—is more forgiving and actually leaves some ground for Flynn to make headway. The burden on a defendant to withdraw a guilty plea prior to sentencing is not all that high. As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit summarized its case law in 2007:

A defendant may withdraw a guilty plea prior to sentencing if he "can show a fair and just reason for requesting the withdrawal." FED.R.CRIM.P. 11(d)(2)(B). Although "[w]ithdrawal of a guilty plea prior to sentencing is to be liberally granted," United States v. Taylor, 139 F.3d 924, 929 (D.C.Cir.1998), we review a district court's refusal to permit withdrawal only for abuse of discretion, United States v. Hanson, 339 F.3d 983, 988 (D.C.Cir.2003). In reviewing such a refusal, we consider three factors: "(1) whether the defendant has asserted a viable claim of innocence; (2) whether the delay between the guilty plea and the motion to withdraw has substantially prejudiced the government's ability to prosecute the case; and (3) whether the guilty plea was somehow tainted." Id. (quoting United States v. McCoy, 215 F.3d 102, 106 (D.C.Cir.2000) (quoting Taylor, 139 F.3d at 929)).

The cited case Taylor may give Flynn some running room. He is claiming his former lawyers at Covington had conflicts of interest, a matter on which the factual record is wholly undeveloped and currently just a set of allegations. Taylor might be read to require that he get an evidentiary hearing to develop the point.

At the end of the day, however, Flynn will still have to convince Judge Sullivan that he has asserted a viable claim of innocence and that his plea is tainted. Neither of these points is obvious at all. One thing Flynn does not appear to be claiming, after all, is that his answers to questions at that FBI interview were accurate.

Flynnvestigating the Documents

So what’s actually in all of this released material? The material Powell has released from Covington consists of two emails, both largely redacted.

The first, from Flynn’s Covington attorney Robert Kelner to his co-counsel Stephen Anthony, dates to March 18, 2018, and shows Kelner writing to Anthony, “We have a lawyers’ unofficial agreement that they are unlikely to charge Junior in light of the Cooperation Agreement.” The second, dated March 18, 2018, is from Anthony to Kelner and two Covington colleagues. The only unredacted text in the email reads, “The only exception is the reference to Michael Jr. The government took pains not to give a promise to MTF [presumably referencing Flynn] regarding Michael Jr., so as to limit how much of a ‘benefit’ it would have to disclose as part of its Giglio disclosures to any defendant against whom MTF may one day testify.” (Under Giglio v. United States, the government must inform defendants of information concerning immunity deals that might impeach a witness’s credibility.)

Flynn’s current lawyers try to cast this as evidence of prosecutorial misconduct—a gross effort to threaten Flynn with the prosecution of his son combined with an effort to cover it up. In fact, if prosecutors did use Flynn’s son as leverage, this is within the range of normal prosecutorial hardball. Flynn’s consulting group, with which his son was employed, engaged in practices that raised legal questions under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, exposing both father and son to potential criminal liability. (And that’s before we get to the reported involvement by both Flynns in a possible plot to kidnap cleric Fethullah Gulen on behalf of the Turkish government.) Prosecutors were apparently willing to forego other charges against Flynn in exchange for his cooperation and plea to the single felony. According to the Covington emails, the prosecutors apparently would not promise to forego further charges against Flynn’s son, although they signaled that they were “unlikely” to move forward against him if they received satisfactory cooperation from his father.

Leaning on a potential defendant for cooperation using the criminal liability of family members as leverage is not unheard of. This does not mean the practice is beyond criticism—but the handling of Flynn’s case is not some kind of aberration, let alone the sort of conscience-shocking thing that might justify a dismissal.

And to the extent any nod-and-a-wink arrangement on Flynn Jr. would raise any kind of Giglio issue, it certainly does not with respect to Flynn, who was obviously aware of the predicament his son faced and any role of his plea in alleviating it. That issue would only arise, as the Covington email reflects, if Flynn’s testimony were used against someone else and any arrangement with respect to his son were not disclosed.

The first batch of documents provided by Jensen and released on April 29 contains two email chains within the FBI from Jan. 23 and 24, 2017—the day before the FBI spoke with Flynn in the interview for which he was later charged with lying, and the day of the interview, respectively—along with a page of handwritten notes, partially redacted and dated Jan. 24. The documents appear to show conversations within the bureau regarding how to handle the interview and Flynn’s case.

One email chain shows an exchange between FBI lawyer Lisa Page (who was then working in the office of FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe) and FBI official Peter Strzok (who was working on the Russia investigation), as well as an unidentified individual in the FBI’s Office of General Counsel. This chain shows Page and the Office of General Counsel official discussing if and when it was appropriate or necessary to notify an interviewee that lying to a federal official is a criminal offense under 18 U.S.C. § 1001, the statute under which Flynn pleaded. Page writes asking whether “the admonition re 1001 could be given at the beginning of the interview” or whether it has “to come following a statement which agents believe to be false”; the other correspondent writes that, “if I recall correctly, you can say it at any time,” and indicates that he or she will double-check.

The next email, sent early in the morning of Jan. 24, is from Strzok to a redacted email address; then-FBI General Counsel James Baker is copied on the email, along with another redacted address. Strzok’s note contains a list of questions for McCabe to consider how he might want to answer in advance of a phone call with Flynn—that is, questions Flynn might ask him about the ongoing FBI investigation. From the Mueller report and other internal FBI documents released by Powell during the Flynn litigation, we know that McCabe spoke with Flynn by phone around noon on Jan. 24 and informed him that the FBI wanted to interview him about his contacts with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak; Flynn agreed, and Strzok and another agent interviewed him at around 2:15 p.m. that same day. With that in mind, the Jan. 24 email appears to show the bureau preparing McCabe for how to discuss his request for an interview with Flynn.

The last document in this tranche is a page of handwritten notes, with some redactions, dated Jan. 24; it is not clear whether the notes were written before the Flynn interview was conducted or after it. The writer seems to be sketching out thoughts—it is not clear whose—on how the bureau should navigate the politically tricky investigation, particularly regarding whether or not the FBI should allow Flynn to lie or confront him with evidence of his falsehood. The notes appear to show the writer moving toward the argument that the bureau should take the latter path. “What’s urgent?” the writer asks. “Truth/Admission or to get him to lie, so we can prosecute him or get him fired?” The notes go on:

- We regularly show subjects evidence with the goal of getting them to admit their wrongdoing

- I don’t see how getting someone to admit their wrongdoing is going easy on him

- If we get him to admit to breaking the Logan Act, give this to DOJ and have them decide

- Or, if he initially lies, then we present him [redacted] and he admits it, document for DOJ, and let them decide how to address it

- If we’re seen as playing games, WH [White House] will be furious

- Protect our institution by not playing games

Flynn’s new lawyers cite these notes, which were presumably written by then-FBI counterintelligence chief Bill Priestap, as supposed smoking-gun evidence that the FBI was seeking to entrap Flynn in a lie. The trouble with that argument is that absolutely nothing forced Flynn not to tell the truth in that interview. And while FBI officials appear to have discussed the strategic purpose of the interview, there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with that. To be sure, a possible criminal prosecution based on the Logan Act case was weak leverage, given that the statute has virtually no history of enforcement, but agents hold relatively weak leverage over witnesses all the time. And yes, it’s wrong for the bureau to set up an interview in the absence of a viable case in order to induce a witness to lie for purposes of prosecution, but there’s no evidence that is what happened—merely evidence that the possibility was on a list of possible strategic goals for the interview. And yes, the bureau will sometimes confront a witness with a lie and specifically warn the person about lying being a felony, but that is not a legal requirement.

In fact, the Flynn interview gave Flynn every opportunity to tell the truth. As the FBI’s partially redacted memo documenting Flynn’s interview reflects, the questions were careful. They were specific. The agents, as Strzok later recalled in a formal FBI interview of his own, planned to try to jog Flynn’s memory if he said he could not remember a detail by using the exact words they knew he had used in his conversation with Kislyak. And Flynn, as he admitted in open court—twice—did not tell the truth. That is not entrapment or a set-up, and it is very far indeed from outrageous government conduct. It’s conducting an interview—and a witness at the highest levels of government lying in it.

The second batch of documents produced by Jensen and released on April 30 contains a draft FBI memo closing Flynn’s case (which was never finalized), along with an internal FBI email chain and what appear to be internal FBI text messages or instant messages. It appears that the FBI drafted a memo to close the case on Flynn, a memo that is dated Jan. 4, 2017, but was likely written earlier. But FBI leadership then decided to keep the case open.

The memo describes how the FBI opened a case on “CROSSFIRE RAZOR” (clearly, from the description, Flynn) “based on an articulable factual basis that CROSSFIRE RAZOR (CR) may wittingly or unwittingly be involved in activity on behalf of the Russian Federation which may constitute a federal crime or threat to the national security.” After describing investigative steps taken by the bureau, the memo states that the “CH team” (a reference to the bureau’s name for the Russia investigation, “Crossfire Hurricane”) “determined that CROSSFIRE RAZOR was no longer a viable candidate as part of the larger CROSSFIRE HURRICANE umbrella case,” and that the bureau is therefore closing the case. Notably, the memo flags that “FBI management” requested that Flynn not be interviewed.

A chain of messages included in the documents shows communications between Strzok and a redacted individual regarding the memo. On Jan. 4, Strzok messaged the other person to tell him or her not to close the case, apparently at the direction of FBI leadership. It’s not clear from the documents what caused the change in course, but another message between two redacted individuals notes a comment by Strzok suggesting that FBI leadership decided to interview Flynn after all.

The documents themselves don’t reveal the reason for the shift. But reporting by the New York Times provides a hint. According to the Times, the Jan. 4 decision not to close the case may have resulted from the FBI’s discovery that Flynn had spoken with Kislyak in the previous days and advised Russia against retaliating against U.S. sanctions levied by the Obama administration in response to Russian election interference—the matter about which FBI agents eventually interviewed Flynn, and about which he lied repeatedly to them. The issue was of concern to the bureau in part because it appeared that Flynn had lied to Vice President Mike Pence about those contacts as well, and the FBI became worried that Flynn’s falsehoods “posed a blackmail risk,” the Times writes. In other words, there’s a very good explanation for why the FBI made a U-turn on closing Flynn’s case: When the memo was drafted, the writer wasn’t yet aware of the most concerning conduct by Flynn.

In his recent book, “The Threat,” McCabe describes the chain of events that seems to have led to the discovery of Flynn’s conversation with Kislyak—and why the bureau wasn’t aware of that information before:

Near the end of December, the administration and National Security Council prepared sanctions on Russia as punishment for their involvement in the election … The sanctions were announced on December 29.

The next day, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, issued an unusual and uncharacteristic statement, saying that he would take no action against the United States in retaliation for those sanctions. The PDB [Presidential Daily Brief] staff decided to write an intelligence assessment as to why Putin made the choice he did. They issued a request to the intelligence community: Anyone who had information on the topic was invited to offer it for consideration. In response to that request, the FBI queried our own holdings. We came across information indicating that General Mike Flynn, the president-elect’s nominee for the post of national security advisor, had held several conversations with the Russian ambassador to the U.S., Sergey Kislyak, in which the sanctions were discussed. The information was something we had from December 29. I had not been aware of it. My impression was that higher-level officials within the FBI’s counterintelligence division had not been aware of it. The PDB request brought it to our attention.

...We felt we needed time to do more work to understand the context of what had been found—we don’t just run out and charge someone based on a single piece of intelligence. We use intelligence as the basis for investigation.

Quite apart from this history, there is nothing wrong with the bureau contemplating the closure of a case without interviewing the subject, then deciding not to close it and that an interview is appropriate, proceeding with the interview, and prosecuting the individual for lying in that interview. The emails do not make out even a colorable case of misconduct by anyone.

The remainder of the tranche contains an email chain between Strzok, Page, and other FBI officials including Priestap. The emails are dated Jan. 22, two days before the Flynn interview, and show that officials were still debating how to handle the Flynn case at this point and had not yet settled on an FBI interview of Flynn. Strzok suggests providing Flynn with a defensive briefing—that is, alerting him of the bureau’s concerns that the Russian government may be using Flynn for its own ends—and “see[ing] what he does with that.” Another, redacted correspondent writes that, “[a]t the very least, we need to debrief or interview [Flynn] (unless told not to).” This last writer also notes, “If we usually tell [the White House], then I think we should do what we normally do”—perhaps voicing a desire to inform the White House of the FBI’s counterintelligence concerns regarding Flynn, though it is not clear. (The email chain also contains a reference to what is presumably another Crossfire Hurricane subject, “CROSSFIRE TYPHOON,” but all other information about this is redacted.)

Messages between Strzok and Page dated Jan. 23 and Jan. 24 describe disagreement among FBI leadership—seemingly Priestap, McCabe and FBI Director James Comey—though it is not clear specifically what is at issue. Another message from Jan. 24 shows Strzok alerting a redacted correspondent about an email containing suggestions for how McCabe should prepare for a call with Flynn—the same email contained in the first batch of documents from Jensen and described above.

Finally, messages between Strzok and Page dated Feb. 10 appear to show the two discussing unspecified edits to an unidentified document. The Times writes that the messages concern,

editing notes on the questioning of Mr. Flynn. His lawyers said they were further evidence that the F.B.I. doctored the interview notes known as a 302, a claim that the judge overseeing Mr. Flynn’s case, Emmet G. Sullivan of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, has previously rejected.

None of this material gives rise to a colorable claim of misconduct, and as the Times notes, Sullivan has already rejected the notion that the 302 was doctored. As the judge wrote back in December: “[T]he Court agrees with the government that there were no material changes in the interview reports, and that those reports track the interviewing FBI agents’ notes.” Sullivan went on: “Having carefully reviewed the interviewing FBI agents’ notes, the draft interview reports, the final version of the FD302, and the statements contained therein, the Court agrees with the government that those documents are ‘consistent and clear that [Mr. Flynn] made multiple false statements to the [FBI] agents about his communications with the Russian Ambassador on January 24, 2017.’”

Flynnterpreting the Facts and the Law

In light of all of this, let’s consider the likelihood of positive outcomes for Flynn in ascending order of probability.

The least plausible outcome is that Flynn will be “exonerated” or “cleared” as a result of anything that has happened. Flynn isn’t within a country mile of being able to establish outrageous government conduct, and Judge Sullivan is most unlikely to dismiss the case as a result of these releases.

A somewhat more likely possibility is that the judge will allow him to withdraw his guilty plea. This would, of course, expose Flynn to the full range of possible charges he potentially faced. It might also expose his son to possible indictment. But that assumes that the Justice Department under Attorney General Barr would actually seek to protect the prosecutorial equities of the United States, something Barr has already declined to do once in the Flynn case alone. So withdrawal of the plea could be a windfall for Flynn or a disaster depending on what happens next. To get the plea withdrawn, Flynn would have to convince Sullivan that the alleged Covington conflicts are real and genuinely impaired his defense, and that he has a viable claim of innocence. This is a tall order, but he may be entitled to an evidentiary hearing on the matter and who knows what could arise out of that? The likelihood of Flynn getting the plea scotched is not high, but not trivial either.

The third possibility is that Barr will step in again. As we noted, he has already done this once in the Flynn case—the government suddenly agreed that Flynn’s conduct merited a sentence of probation after previously advocating up to six months’ incarceration—and he has appointed Jensen to review it too. He’s got his eye on the matter, and what he has planned is unclear. Suffice it for now to say that there’s reason to worry the Justice Department will not pursue the matter aggressively under Barr’s leadership, particularly if a plea withdrawal happens and the question of actually prosecuting the original case comes back on the table.

Finally, there’s the president. Trump has not ruled out pardoning Flynn—and has recently railed against the prosecution. Flynn’s most likely path out of the criminal justice system is through presidential clemency, which could arrive any day and with no warning. A great deal of the legal machinations in court and the verbal machinations in the media may well be aimed not at the legal process but at inducing the president to finally grant Flynn a pardon.

.jpg?sfvrsn=676ddf0d_7)