The Revolt of the Judges: What Happens When the Judiciary Doesn’t Trust the President’s Oath

It’s been a busy 24 hours in the increasingly fascinating relationship between President Trump and the federal judiciary.

First, a federal district judge in Hawaii entered a nationwide temporary restraining order enjoining enforcement of the two key provisions of Trump’s revised travel ban executive order.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

It’s been a busy 24 hours in the increasingly fascinating relationship between President Trump and the federal judiciary.

First, a federal district judge in Hawaii entered a nationwide temporary restraining order enjoining enforcement of the two key provisions of Trump’s revised travel ban executive order.

A few hours later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals declined to review en banc the court’s earlier panel decision respecting the first version of the executive order. That decision was accompanied by a stinging dissent by Judge Jay Bybee and four of his colleagues, who argued that the much-ballyhooed panel decision represented “a clear misstatement of law,” “neglect[ing] or overlook[ing] critical cases by the Supreme Court and by our court making clear that when we are reviewing decisions about who may be admitted into the United States, we must defer to the judgment of the political branches.”

Early this morning, a district court in Maryland stepped in and also enjoined the new order on a nationwide basis, though only part of it.

Meanwhile, yet another district judge, this one in Washington (actually the same judge who initially enjoined the original order), declined to hold that the preliminary injunction of the first order applied to the second order as well. And he also held back from issuing a similar order from the bench in a new case, instead taking the matter under advisement.

And the President, of course, responded to it all with his characteristic lack of regard for his own litigation interests, declaring at a campaign-style rally last night that, “The order [the Hawaii federal district judge] blocked was a watered-down version of the first order that was also blocked by another judge and should have never been blocked to start with.” He went on to declare, “I think we ought to go back to the first one and go all the way, which is what I wanted to do in the first place.”

This afternoon, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer announced that the administration intends to appeal the preliminary injunction granted in Maryland “soon” and will also seek “clarification” regarding the temporary restraining order granted in Hawaii.

There’s quite a lot going here. There’s a legal debate, already ongoing, about both the propriety of the President’s order and the propriety of the judicial responses to it. But there’s also another meta-legal discussion to be had here. And it’s a discussion that connects directly back to a piece we wrote recently on what happens when people—including judges—don’t take the President’s oath of office seriously.

To put the matter bluntly: why are so many judges being so aggressive here?

The legal disputes are both interesting and important. But this meta-legal question strikes us, at least, as far more important and far-reaching. And we think the answer lies in judicial suspicion of Trump’s oath. The question goes to the manner in which we can expect the judiciary to interact with President Trump on this and other issues throughout his presidency. It goes, not to put too fine a point on it, to the question of whether the judiciary means to actually treat Trump as a real president or, conversely, as some kind of accident—a person who somehow ended up in the office but is not quite the President of the United States in the sense that we would previously have recognized.

But let’s start with the law.

When the next executive order came out ten days ago, one of us (Ben) analyzed it along the following lines: Because the revised order was set to apply after a waiting period and did not affect current visa-holders or legal permanent residents, the order “[would] not cause people to be pulled off planes, or have their visas revoked, or suddenly be subject to detention at a port of entry.” As such, it seemed at the time that it would be “significantly harder to find plaintiffs with a cognizable injury” to challenge it. The Justice Department was clearly aware of this, writing in filings in both the Western District of Washington and the District of Columbia that “the New Executive Order does not present a need for emergency litigation.”

Ben also predicted that, even if the ACLU or similar organizations were able to find plaintiffs with standing, they would find the new order much more difficult to attack in court. The revised order began with “a significant set of factual findings which constitute some kind of administrative record to which a court will owe deference”—unlike the original order, which contained no such material. It also provided a set of categorical exemptions to certain groups of travelers: those holding valid visas or green cards, those who had previously been granted asylum or refugee status, and those protected under the Convention Against Torture. And it built in a major loophole in the form of giving “consular officers or Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials discretion to waive the ban ‘on a case-by-case basis.’”

All this, it seemed, would be a great help to the government in future litigation. Ben argued, in conclusion:

To be sure, there’s a gestalt litigation question here: whether the improper motivations behind this entire project of banning entry from certain countries, motivations announced repeatedly by Trump himself and his campaign and administration surrogates, have injured his litigation posture so indelibly that courts will continue to throw roadblocks in the way. But I suspect that at some point—assuming, no doubt generously, that Trump can manage to shut up—the courts will have to act on the basis of the administrative record without consulting the atmosphere overmuch.

It is early yet in the litigation, but it’s fair to say that at least in two of the first three district courts to rule on the matter over the past day, none of these predictions looks especially prescient. Neither Judge Derrick Watson in Hawaii nor Judge Theodore Chuang in Maryland had much trouble finding that plaintiffs before them had standing to sue. Nor did either find that the more careful lawyering which supposedly would benefit the revised order made much difference in the substantive legal analysis. (For that matter, neither did Judge William Conley in the Western District of Wisconsin, who granted a temporary restraining order last week in the case of a Syrian refugee trying to bring his wife and daughter to the United States from Aleppo.) The taint, at least so far, has indeed been indelible.

Granting plaintiffs’ motion for a temporary restraining order in Hawaii v. Trump, Judge Watson largely skipped over the statutory basis for the suit under the Immigration and Nationality Act, focusing instead on the State of Hawaii and plaintiff Ismail Elshikh’s Establishment Clause claims. The judge determined that Hawaii successfully demonstrated standing based on its proprietary interests in the financial well-being of its universities and tourism industry—the same argument used by the State of Washington before the 9th Circuit regarding the first order—and that Elshikh, an Egyptian-American Muslim, had standing as a consequence both of his “perception that the Government has established a disfavored religion” and his fear that his Syrian mother-in-law would not be granted a visa to enter the country. Then, relying heavily on statements by Trump and his team, and with particularly rip-roaring language, Judge Watson held that the EO’s primary purpose was not “secular” but based instead on animus toward Muslims. To the government’s contention that the order did not target Islam because many Muslims around the world were unaffected, the judge wrote: “The illogic of the Government’s contentions is palpable. The notion that one can demonstrate animus toward any group of people only by targeting all of them at once is fundamentally flawed.”

Judge Chuang’s ruling early this morning in International Refugee Assistance Project v. Trump was more measured and analytical in tone but none the less emphatic and ultimately similar in legal logic. On the question of standing, the judge found that the “significant fear, anxiety, and insecurity” created in the individual Muslim plaintiffs by the order represented sufficient injury to pursue their Establishment Clause claim, and that the plaintiffs’ concern that their relatives will be turned back from the United States was ripe despite the waiver provision in the new order. In contrast to Judge Watson’s opinion, Judge Chuang spent some time in the weeds of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) before moving on to the Establishment Clause.

He held that for the purposes of the case before the court, the INA’s broad grant of power to the president to suspend entry into the country from “immigrants or nonimmigrants” does not supersede the Act’s provision barring discrimination on the basis of nationality in the visa issuance process. Like Judge Watson, however, Judge Chuang went on to find that the primary purpose of the order was other than secular under the first prong of the Lemon test, likewise using statements by Trump and his aides to prove the point. While Judge Chuang’s preliminary injunction was nationwide, like Judge Watson’s TRO, he constrained the injunction to Section 2 of the order—restricting travel from the six named countries—and allowed Section 6, on the granting of refugee status, to stand.

We don’t mean here to do an exhaustive legal analysis of either court’s work. But suffice it to say that you don’t have to be a Trumpist to have questions. The Maryland opinion seems significantly stronger than the Hawaii opinion, but both have substantial holes.

For one thing, at least some of the standing analysis seems off. Judge Watson, for example, found standing for a man on grounds that his mother-in-law might not be able to visit him and his wife because of the ban, though she had not yet even sought a waiver of the ban’s applicability to her; in other words, it’s totally unclear that she will even be meaningfully impacted by the new version of the policy. In fact, the EO specifically lists visitation of a close family member who is also a U.S. citizen or resident as possible grounds for a waiver. Similarly, a standing analysis that made sense the first time around by a state—that its university would be adversely affected—seems at least a little premature without knowing anything about how many people associated with that university will actually be kept out of the country. This time around, after all, student study is listed explicitly as possible basis for a waiver. There may well be standing here, but the opinions are hasty on the points.

More importantly, both the Bybee dissent in the 9th Circuit en banc and commentary by Josh Blackman and Peter Margulies on this site should give commentators at least a little bit of pause on a number of different substantive grounds:

First, the Establishment Clause analysis in both opinions is simply too glib. Blackman makes a powerful case that courts just don’t normally do Establishment Clause analyses in visa issuance cases involving people abroad. And there certainly doesn’t seem to be any kind of working rule that the government must have a secular purpose of the type that Lemon v. Kurtzman normally requires in situations like these.

Moreover, Bybee makes a persuasive case that the the 1972 decision of Kleindienst v. Mandel—in which the Supreme Court held that courts should not look behind a facially valid purpose on the part of the political branches with respect to visa issuance policies—deserves, at a minimum, more attention than these district courts (and the 9th Circuit panel) are now giving it. Whether it truly controls, as he argues, may be a closer question given some other Supreme Court cases, but the ease with which the courts are waving it away suggests at a minimum that a large number of judges are getting well out ahead of settled law.

Our point here is not that the district judges are clearly wrong. It’s merely that they are not clearly right—on a whole lot of points. And in the face of real legal uncertainty as to the propriety of their actions, they are being astonishingly aggressive. It is not, after all, a normal thing for a single district judge to enjoin the President of the United States nationally from enforcing an action that the President contends is a national security necessity, much less an action taken pursuant to a broad grant of power by the legislature in an area where strong deference to the political branches is a powerful norm. And it really isn’t a normal thing for multiple district judges to do so in quick succession—and, moreover, to do so in the face of substantial uncertainty as to the actual parameters of the constitutional and statutory law they are invoking and powerful arguments that they are exceeding their own authority.

So what’s going on here?

One possibility is that we’re dealing with a bit of a fluke. The President behaved very badly, not merely in issuing a grotesque policy in a grotesque fashion but then in attacking the judges tasked with hearing the litigation his conduct spawned. In this understanding of what is happening, some—but not all—judges are responding overly emotionally and are going out on any number of legal limbs in response in their attempts to bat Trump back. Notably, even Bybee’s otherwise scathing dissent pushes back quite hard against “the personal attacks on the distinguished district judge and our colleagues,” which, he writes, “were out of all bounds of civic and persuasive discourse” and “treat the court as though it were merely a political forum in which bargaining, compromise, and even intimidation are acceptable principles.”

If this reading is correct, we can expect something of a reversion to more normal judicial behavior as larger number of higher-level appellate judges get involved and more time elapses, particularly if Trump is able to show some modicum of self control over the coming weeks and months. (This is admittedly a very big if—especially given Trump’s intemperate comments yesterday evening.) If this is what we’re dealing with, expect Trump to begin prevailing as more appellate courts begin dragging the lower courts back towards more conventional legal analyses.

A second possibility is that these judges, while indeed somewhat ahead of the state of the law, are correctly anticipating its directional momentum. In other words, perhaps we are experiencing one of those shocks to the system that punctuates the equilibrium of a certain body of case law; that is, maybe Trump’s behavior is forcing a reevaluation of both the application of the Establishment Clause to visa issuance and the scope of deference the courts owe the president on certain national security-inflected immigration matters. Robert Loeb made a similar point on Lawfare earlier today, arguing that the two executive orders “threaten[] to undermine the broad judicial deference that has applied to the Executive in the immigration context for more than 100 years.”

But also there is a third possibility, and we should be candid about it: Perhaps everything Blackman and Margulies and Bybee are saying is right as a matter of law in the regular order, but there’s an unexpressed legal principle functionally at work here: That President Trump is a crazy person whose oath of office large numbers of judges simply don’t trust and to whom, therefore, a whole lot of normal rules of judicial conduct do not apply.

In this scenario, the underlying law is not actually moving much, or moving or at all, but the normal rules of deference and presumption of regularity in presidential conduct—the rules that underlie norms like not looking behind a facially valid purpose for a visa issuance decision—simply don’t apply to Trump. As we’ve argued, these norms are a function of the president’s oath of office and the working assumption that the President is bound by the Take Care Clause. If the judiciary doesn’t trust the sincerity of the president’s oath and doesn’t have any presumption that the president will take care that the laws are faithfully executed, why on earth would it assume that a facially valid purpose of the executive is its actual purpose?

In this scenario, there are really two presidencies for purposes of judicial review: One is the presidency when judges believe the president’s oath—that is, a presidency in which all sorts of norms of deference apply—and the other is a presidency in which judges don’t believe the oath. What we may be watching here is the development of a new body of law for this second type of presidency.

This, we suspect, is the true significance of all of the references in both district court opinions to the many statements made by Trump and his aides about the Muslim ban and the true purpose of the policy effectuated in both orders. These references present, of course, as discussions of whether there is truly a secular purpose to the policy in an Establishment Clause analysis using the Lemon test. But there’s at least a little more going on here than that. The lengthy recitations of large numbers of perfectly objectionable presidential statements about Muslims coexist with a bunch of other textual indicia showing not merely that the judges doubt Trump’s secular purpose but that they doubt the good faith of his purpose at all—indeed, that they suspect that he is simply lying about his own motivations.

For example, Judge Chuang pointed to the fact that “the core concept of the travel ban was adopted in the First Executive Order, without the interagency consultation process typically followed on such matters” as evidence that “the national security purpose is not the primary purpose of the ban.” Given that the first order was issued “without receiving the input and judgment of the relevant national security agencies,” the national security rationale behind the order is post hoc at the very least. Judge Chuang further argues that under Lemon, it doesn’t actually matter if the national security rationale is legitimate—all that matters is that it’s secondary to the motive of religious animus. He also terms the case “highly unique,” again suggesting that he’s not describing a regular mode of judging. He’s describing a mode of engaging with a President who is acting in bad faith.

In his essay on the second executive order and the Establishment Clause, Blackman alleges of Judge Leonie Brinkema’s analysis of the first executive order that, “At its heart, the court’s Establishment Clause analysis isn’t about the executive order. Rather, it is about the person who signed it.” Writes Blackman:

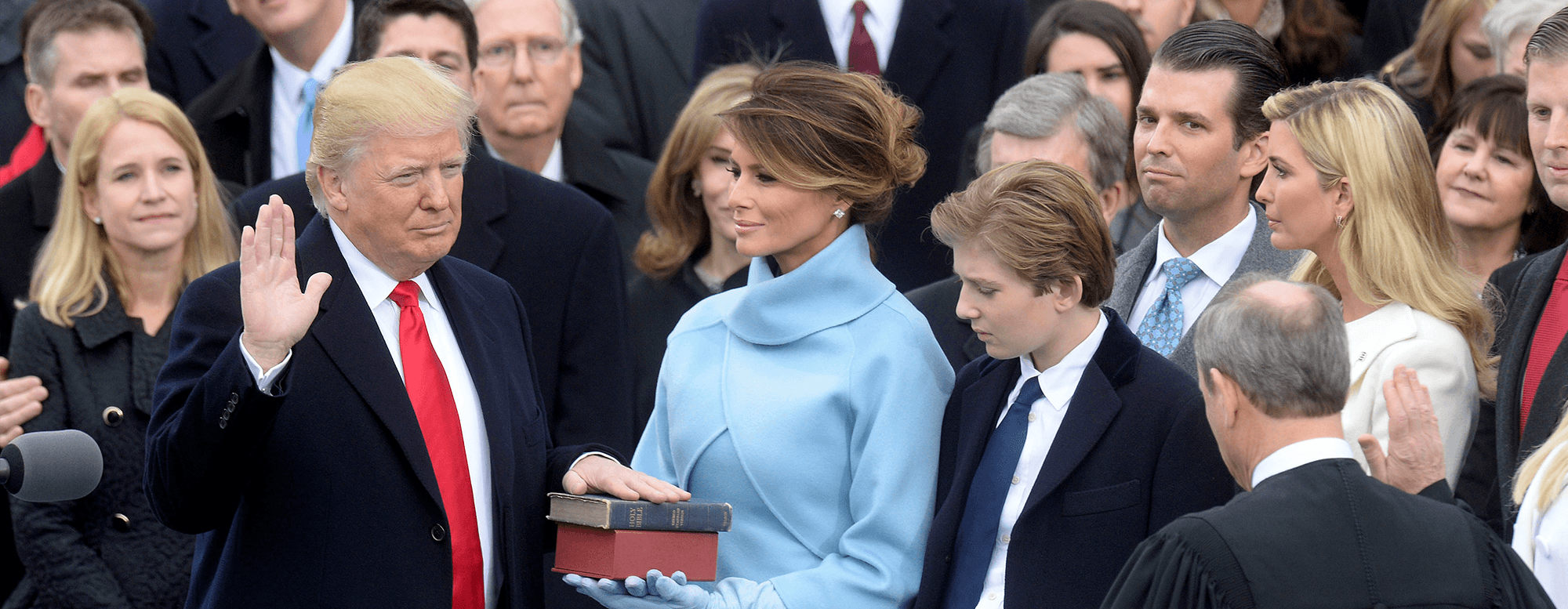

Judge Brinkema has applied a “forever taint” not to the executive order, but to Donald Trump himself. For example, the government defended the selection of the seven nations in the initial executive order because President Obama approved a law that singled out the same seven nations for “special scrutiny” under the visa waiver program. Judge Brinkema rejected this reasoning: “Absent the direct evidence of animus presented by the Commonwealth, singling out these countries for additional scrutiny might not raise Establishment Clause concerns; however, with that direct evidence, a different picture emerges.” That is, if Barack Obama selected these seven countries for extreme vetting, it would be lawful, because he lacks the animus. But because Donald Trump had that animus, it would be unlawful. No matter that Trump excluded forty-three other Muslim-majority nations that account for 90 percent of the global Muslim population. Even though three of the included nations are state-sponsors of terrorism! It will always a “Muslim ban” because of comments he made on the O’Reilly Factor in 2011, a policy he adopted in 2015, and abandoned after his lawyers told him it was illegal. She admits as much. “A person,” she writes, “is not made brand new simply by taking the oath of office.” Not the policy. The person. Trump.

We suspect there is a lot of truth to this. The question is whether that decoupling of the presidency from the person of the president, which we anticipated in our original essay on the oath, is quite as indefensible as Blackman assumes—or whether it’s an inevitable consequence of vesting someone as volatile and fundamentally disingenuous as Trump with “the Executive Power” of the United States of America.

The other question is whether the higher courts—including, ultimately, a majority of the Supreme Court—will share Brinkema’s sensibility or Blackman’s on the matter. There is no doubt that Blackman’s and Bybee’s approach represents the traditional judicial posture. It is a posture in which the judiciary has certain institutional obligations to the executive branch; in which those obligations exist independent of the person who embodies the executive branch at any given moment in time; in which the deference and respect owed the president exist largely in abstraction from the President’s fidelity to his oath or to the Take Care clause; in which that fidelity is non-judiciable in any event; and in which presidential misconduct does not warrant judicial action outside of the agreed-upon judicial function.

These norms are what Bybee is referring to in this discussion of elections having consequences:

As tempting as it is to use the judicial power to balance those competing interests as we see fit, we cannot let our personal inclinations get ahead of important, overarching principles about who gets to make decisions in our democracy. For better or worse, every four years we hold a contested presidential election. We have all found ourselves disappointed with the election results in one election cycle or another. But it is the best of American traditions that we also understand and respect the consequences of our elections. Even when we disagree with the judgment of the political branches—and perhaps especially when we disagree—we have to trust that the wisdom of the nation as a whole will prevail in the end.

But there is another possible approach to Trump on the part of judges, and it so far seems to be the majority response and the prevailing one. (Remember, after all, that Bybee is in dissent here). And that is the one we hypothesized in our piece on the presidential oath of office:

Imagine a world in which other actors have no expectation of civic virtue from the President and thus no concept of deference to him. Imagine a world in which the words of the President are not presumed to carry any weight. Imagine a world in which far more judicial review of presidential conduct is de novo, and in which the executive has to find highly coercive means of enforcing message discipline on its staff because it can’t depend on loyalty. That’s a very different presidency than the one we have come to expect.

It’s actually a presidency without the principle that we separate the man from the office. It’s a presidency in which we owe nothing to the office institutionally and make individual decisions about how to interact with it based on how much we trust, like, or hate its occupant.

The question is whether the revolt of the judges we are currently witnessing is the beginning of this world.