U.S. and China Sign "Phase One" Trade Deal but Leave Key Issues Unresolved

Lawfare's biweekly roundup of U.S.-China technology policy news.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

U.S. and China Sign “Phase One” Trade Deal but Leave Key Issues Unresolved

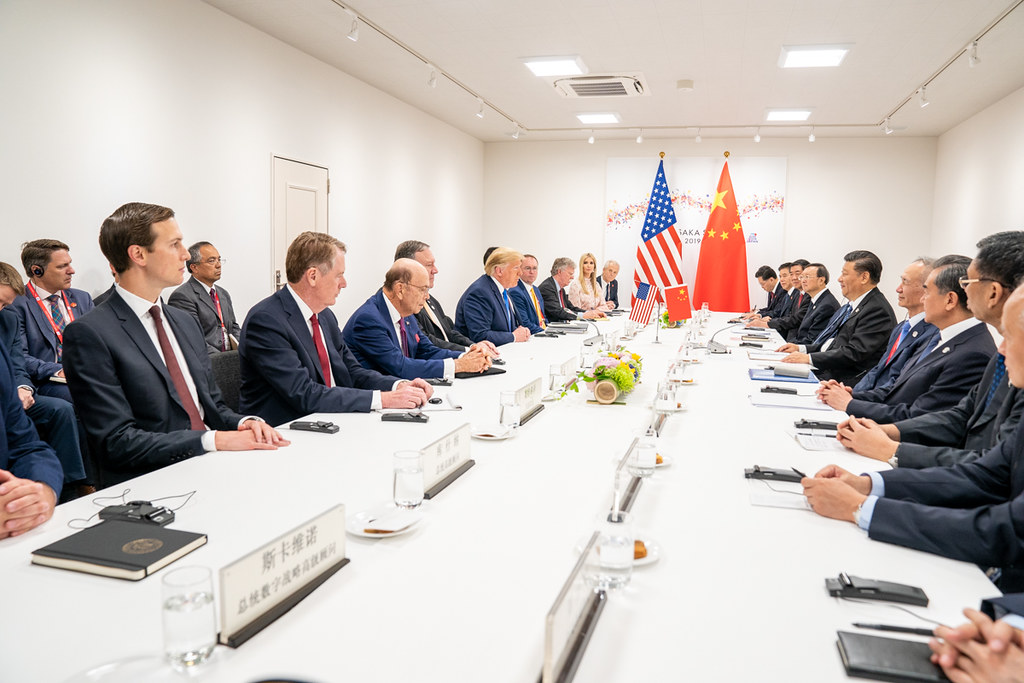

On Jan. 15, the United States and China signed a “phase one” trade deal that the Trump administration says will provide safeguards for intellectual property, boost sales of U.S. goods and services in China, and provide greater access to the Chinese market for U.S. companies. While the president praised the deal as a “momentous” step, critics have noted that the deal leaves largely untouched key issues concerning the structure of the Chinese economy. In a 2018 report, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) argued that the Chinese economic structure unfairly advantages domestic companies through a system of subsidies, selective enforcement of certain regulations, and practices designed to pressure firms to transfer technology. Others have argued that some of China’s commitments in the new deal—including market access reforms and its pledge to buy soy and pork from the United States—were actions China would have taken or had already taken, even without the agreement. As part of the agreement, the Trump administration canceled tariff increases initially set to take place in December and reduced levies from 15 percent to 7.5 percent on $120 billion in Chinese products. But the phase one agreement leaves in place tariffs on some $370 billion worth of Chinese goods—about 65 percent of total U.S. imports from the People’s Republic. President Trump said the United States would lift the remaining tariffs if the two sides could reach a second, more substantial agreement. Trump added that the United States would aim to start negotiations toward a more comprehensive agreement before November 2020.

After this week’s signing, Vice Premier Liu He, the chief negotiator for the Chinese side, delivered a message from President Xi Jinping, saying that the agreement is “good for China, for the U.S. and for the whole world.” But he added that “China has established a political system and an economic-development model that suits its own characteristics.”

As part of the deal, China has agreed to purchase an additional $200 billion worth of U.S. goods and services by 2021. The commitment includes roughly $50 billion in energy exports, $32 billion in agricultural goods, $77 billion in manufactured goods and an additional $37 billion in services. The deal sets no fixed terms for further Chinese purchases of American goods after 2021. The language of the agreement includes only the vague commitment from China that it continue to make purchases through 2025 based on the “trajectory” of its purchases through 2021.

The agreement includes language aimed at improving intellectual property protections in China; a 2018 USTR report estimated that “Chinese theft of American IP currently costs between $225 billion and $600 billion annually.” But analysts say the deal’s provisions may lack the specificity required to achieve meaningful change. Beijing promised that companies will be able to operate in China “without any force or pressure” to transfer their technology against their will but did not articulate any specific strategies for tackling this problem. Nor has China ever acknowledged that forced technology transfer occurs in the country. The deal also contains fresh assurances—with little in the way of concrete plans—that China will seek to limit requests for information during licensing procedures. The USTR reports that approval processes and licensing procedures offer an avenue through which government officials, while supposedly checking to ensure that companies meet relevant regulatory standards, access sensitive data or technical secrets. China also committed to preventing “electronic intrusions,” through which hackers can steal technical secrets or valuable data.

The deal also promises changes to China’s judicial system. China will shift the burden of production in certain civil cases to the accused, which may help companies litigate more successfully against parties who violate their intellectual property rights. China will also subject those who willfully engage in certain forms of trade secrets theft to criminal proceedings, rather than civilian proceedings. Whether and to what extent these judicial changes help U.S. firms address intellectual property more effectively in the courts remains to be seen.

Speaking about the agreement as a whole, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said the agreement had “real teeth” but noted that the United States would know by the spring whether Beijing had made good on its new promises. The deal implements a procedure by which the United States can ratchet up tariffs if China does not meet its obligations under the agreement. Per the terms of the agreement, a complaint by one party would trigger meetings between officials of both sides. If the two sides cannot ultimately resolve the matter within roughly 90 days, the accusing side can impose tariffs, and the other’s only recourse will be to leave the agreement entirely.

The agreement acts as a cease-fire in a trade war that has lasted for more than 18 months. While markets rose on news of the agreement, many in the American business community have pointed out that economic tensions between the two sides are far from over. Many of the thorniest issues separating the two sides—Chinese economic espionage, subsidies from the Chinese government, and the outsize role of state-owned enterprises in the economy—remain unresolved.

Treasury Department Expands Power to Review Foreign Investment on National Security Grounds

The Treasury Department’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has finalized regulations that apply heightened scrutiny to investors whose acquisitions of U.S. assets may pose national security risks. The regulations, widely seen as targeting investment from China, are scheduled to take effect on Feb. 13. Pursuant to the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), the new regulations will substantially expand CFIUS’s scope. Under the finalized regulations—whose provisions closely resemble those proposed late last year—the Treasury Department will have the power to regulate even transactions in which a foreign entity gains a noncontrolling stake in a U.S. company, where that noncontrolling stake allows the foreign company to gain access to technical information or sensitive data, acquire membership or observer rights on a U.S. company’s board, become involved in the management of critical technology or infrastructure, or otherwise take actions that pose national security risks. Before FIRRMA and its subsequent implementing regulations, CFIUS review had been limited to transactions in which a foreign entity acquired a controlling stake in a firm with U.S. assets.

Under the finalized regulations, CFIUS will require that parties submit a formal notice before acquiring assets considered to be “critical technology,” a term that encompasses certain emerging technologies, nuclear equipment, certain weapons technologies and other technologies subject to export controls. In other cases, CFIUS review will remain voluntary, but foreign firms that do not file with the department risk having their transaction retroactively reviewed and undone. CFIUS’s investigation into TikTok, a video-streaming app owned by Chinese social media company ByteDance, illustrates CFIUS’s willingness to use retroactive reviews. Concerned that ByteDance could be collecting sensitive data on American users and censoring content in accordance with Chinese Communist Party directives, CFIUS has reportedly been in talks with the Chinese social media company over its 2014 acquisition of Music.ly, a Shanghai-based social media service with a foothold in the United States. Although the transaction did not arouse suspicion from U.S. regulators at the time, and although more than five years have passed since it took place, CFIUS can use its broad mandate to require ByteDance to divest or take other remedial measures.

The finalized measures have also expanded CFIUS’s capacity to regulate real estate, an industry that has largely been outside the body’s purview. According to the finalized regulations, the body may scrutinize acquisitions of land near military bases, airports, maritime ports or other sensitive sites.

The finalized regulations will not apply to “excepted investors,” that is, entities from Australia, Canada and the U.K. (though officials indicated that the list of “excepted investors” could grow to include entities from other U.S. allies). The Treasury Department noted that the exception will be granted to these countries because they have “robust intelligence-sharing and defense industrial base integration mechanisms with the United States.” Though exempt from the stricter regime the finalized regulations usher in, investors who qualify for the exception may still be subject to certain baseline CFIUS reviews upon acquiring a controlling stake in U.S. entities that handle sensitive data or critical technologies.

Even before the finalized regulations went into effect, CFIUS had stepped up its scrutiny of Chinese investment. In addition to the TikTok case mentioned above, CFIUS forced Beijing Kunlun Tech, a Chinese gaming company, to sell gay-dating app Grindr, over concerns that the Chinese government might gain access to user data and blackmail users. In March 2018, President Trump quashed Broadcom’s attempted takeover of U.S. chipmaker Qualcomm, reportedly for fear that the deal would help China jump ahead in the race to develop 5G technology. In January 2018, motivated by data security concerns, CFIUS scuttled Alibaba’s attempts to take over U.S. payments company MoneyGram International. CFIUS’s increased focus on Chinese investment and expanding power suggests that even as the United States and China sign a phase one trade agreement, concerns over Chinese efforts to acquire U.S. technology persist.

In Other News

On Jan. 11, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen won reelection, claiming more than 57 percent of the vote. Tsai, a member of the Democratic Progressive Party, had advocated for a tougher stance toward an increasingly authoritarian Beijing, especially as protests have flared in Hong Kong. Her opponent, Han Kuo-yu, the former mayor of Kaohsiung, had supported closer ties to the mainland. But Han found himself on the defensive as the campaign wore on and Taiwanese public opinion turned against Beijing. Tsai’s victory comes despite Beijing’s multipronged disinformation campaign against her.

The U.S. Department of the Interior has decided to stop using civilian drones that include components made by Chinese firms over concerns that Beijing could access photos or data collected by the drones. The decision has generated controversy, as there are currently no firms that make drones with only American products. The move follows a U.S. Army directive banning drones made by DJI, a Chinese firm at the forefront of the global civilian drone industry.

China’s new Cryptography Law, released late last year, has come into effect. The Cryptography Law separates encryption technology into two tiers: “core” cryptography, used to encrypt state secrets; and “commercial” cryptography, used to encrypt other information. Core cryptography will be subject to heightened scrutiny, while citizens and corporations may lawfully use commercial cryptography for their own network and information security, provided they meet certain baseline certification requirements.The law states that multinationals and domestic firms must receive equal treatment, but critics argue that regulators could use the law to access sensitive data on foreign company servers.

The U.S. Army plans to build a specialized task force in the Pacific capable of conducting information, electronic, cyber and missile operations against China or Russia, according to Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy. In an interview discussing the decision, McCarthy said the plans were intended to “neutralize” the investments made by Moscow and Beijing to modernize their respective militaries and exert greater influence in the region. The announcement comes as the United States has increased patrols in the South China Sea. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper says the patrols are designed to signal that the United States intends to protect freedom of navigation in the region.

Commentary

For the New York Times, Eswar Prasad argues that the phase one trade deal included some significant concessions from China but that these concessions may not justify the toll the trade war has taken on the U.S. economy. In the Wall Street Journal, Andy Puzder and Bill Hagerty take a different view, arguing that the deal demonstrates the success of President Trump’s approach to China. In a report commissioned by Huawei, Oxford Economics finds that restrictions on Huawei will significantly increase the cost of building 5G networks for countries like the United States and Australia. In the New York Times, Ai Weiwei argues that Western companies ought to distance themselves from forced labor operations in China.

For Merics, Barbara Kelemen explores a burgeoning trade partnership between China and Afghanistan, arguing that Beijing’s emerging role as a facilitator between the Afghan government and the Taliban highlights its growing influence. In the Financial Times, Camilla Cavendish argues that universities in the U.K. must stand up to Beijing’s efforts to silence Hong Kong pro-democracy protests on British campuses. For Foreign Affairs, Rush Doshi argues that Beijing’s information campaigns in Taiwan provide a glimpse into the Chinese Communist Party’s ambitions to exert sway over media operations around the world. For the South China Morning Post, Emanuele Scimia says that the killing of Qassem Soleimani will have negative ramifications for China, which depends on countries in the Persian Gulf for its oil. By contrast, David Edelstein argues in the Washington Post that China and Russia “might benefit from a simmering crisis between the United States and Iran.”

For Lawfare, Sean Quirk analyzes ongoing legal battles between China and Malaysia—as well as broader disputes between China and its neighbors—over sovereignty in the South China Sea. Hannah Kris highlights, among other things, key points made about China during the seventh Democractic primary debate. The Cyberlaw Podcast discusses, among a host of other topics, restrictions on the use of Chinese technology specified in the National Defense Authorization Act.