Testimony and Executive Privilege in the Senate Impeachment Trial

Senators are debating whether witnesses will appear at the impeachment trial. But if the Senate does vote to hear from witnesses, could executive privilege be utilized to block their testimony?

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

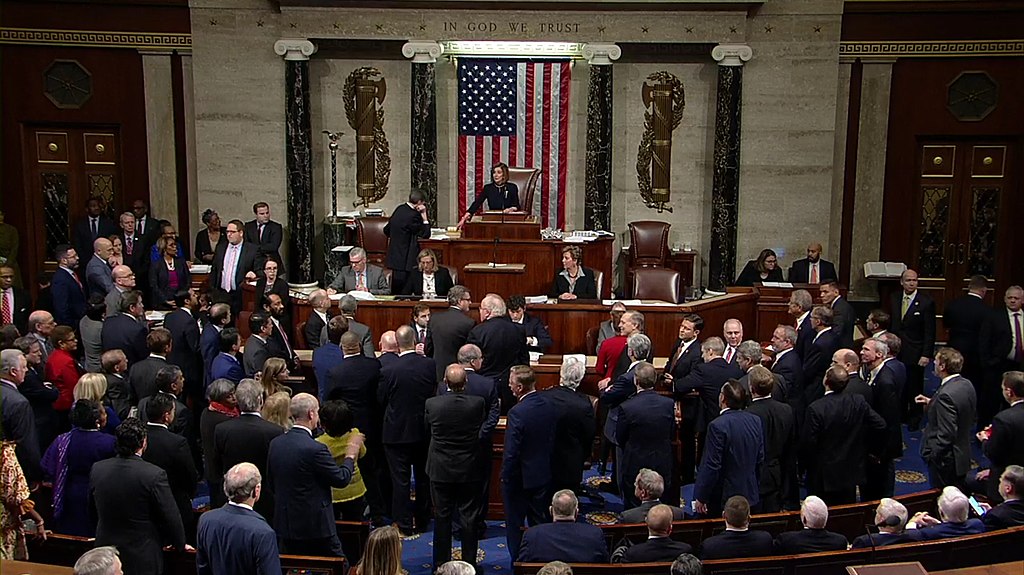

With the House of Representatives set to pass the articles of impeachment to the Senate later today, Jan. 15, senators are still debating whether or not the president’s trial should involve hearing from witnesses. Minority Leader Chuck Schumer continues to call for the testimony of four witnesses—former National Security Adviser John Bolton; current acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney; Mulvaney’s chief deputy Robert Blair; and Michael Duffey, associate director of national security programs at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The White House directed each of these officials not to cooperate with the House impeachment inquiry and to refuse to comply with the House’s requests and subpoenas for their testimony. Sen. Susan Collins has now indicated, however, that she is working with a small group of Republican senators to allow witnesses in the Senate trial. And Rep. Adam Schiff, one of the House managers charged with prosecuting the impeachment case in the Senate, tweeted out a demand that senators hear from witnesses and see documents, attaching a video of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell arguing that witnesses should appear during the Clinton impeachment.

Key to this debate over witnesses is the distinction between law and fact. Factual disputes are why the legal system has witnesses and allows discovery; evidence is necessary for the judge or jury to resolve those disputes and determine what actually happened. Questions of law are different, however. The legal system has doctrines such as summary judgment and judgment as a matter of law in which the judge assumes a particular set of facts are true and then decides whether a person is innocent or a certain party wins based on the applicable law. Appeals typically involve only these questions of law.

The factual basis for the charges against the president are laid out in detail in the articles of impeachment and the House report. The House believed it had sufficient evidence for the charge of abuse of power based on the testimony and documentary evidence it had about the president’s direction to withhold aid to Ukraine without going to the courts to try and force the testimony of witnesses like Bolton, Mulvaney, Blair and Duffey. The legal argument (here one of constitutional interpretation) is that those charges constitute a high crime or misdemeanor warranting the removal of the president from office. The Senate could vote on that legal argument on a motion to dismiss the charges, before considering whether to hear any witnesses. But that is a legal determination that must be made on the basis of the facts and allegations in the House report. Any dispute about the basis for charges in the House report or claim that the evidence is incomplete raises factual questions that would need to be addressed by witnesses and evidence.

If Collins’s effort is successful and Schiff gets his way, Bolton has publicly stated that he will comply with a Senate subpoena for his testimony despite the White House’s claim that he is absolutely immune from such testimony. That is his choice. Previously, he and his former deputy, Charles Kupperman, tried to pursue judicial resolution of the immunity claim and indicated they would not comply with a House subpoena until the courts ruled on the question. But that suit was rendered moot when the House withdrew its subpoena to Kupperman and chose not to subpoena Bolton. Unable to procure a judicial ruling on whether he should testify, Bolton has chosen to comply with any Senate subpoena after considering his “obligations both as a citizen and as former national security adviser.”

What would the other witnesses do if subpoenaed? No one is sure. Unlike Bolton—or former White House counsel Don McGahn—the other three could legitimately claim that they face conflicting commands from two “masters,” the president and the Senate. If the president directed them not to appear, they would have to consider their legal obligations and make a choice. Mulvaney did attempt to join Kupperman’s lawsuit, suggesting he may have had reservations about the administration’s novel application of the testimonial immunity doctrine to impeachment.

There is a further question, however, about the testimony of these witnesses. Shortly after Bolton’s statement, Trump retweeted an argument that, even if Bolton testifies, the “White House can assert executive privilege. It’s not Bolton’s privilege; it’s the president’s. If executive privilege covers anything, it is a talk between president and top advisor on matters of foreign policy.” And OMB has already redacted emails containing some of the information that the Senate would be asking about in responses to requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). As explained below, those redactions necessarily mean that the executive branch believes an assertion of executive privilege over some of the relevant information is at least a possibility. In other words, even if Bolton, Mulvaney, Blair and Duffey all agree to comply with a Senate subpoena to appear, what would they say? And could executive privilege be utilized to block their testimony?

How Should the Senate Decide Whether to Subpoena Witnesses?

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has indicated that when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi sends the articles of impeachment to the Senate for a trial, he will adhere to the procedures employed during the impeachment trial of President Clinton. During that trial, the two sides were permitted to make opening statements before any decision was made on whether to call witnesses. McConnell’s argument is that those procedures were adopted by unanimous vote for the Clinton impeachment and that precedent should be followed here. He has also suggested he has the votes to acquit the president without the need to call any witnesses.

But McConnell’s desired process would implicitly make an important concession about the evidence against the president. Under well-established principles underlying the U.S. judicial system, by analogy, a motion to dismiss should address only questions of law, not questions of fact—in this case, the question of whether the actions the president is alleged to have committed rise to the level of a high crime and misdemeanor. An impeachment trial is not a judicial proceeding, of course, and thus not required to follow the same procedures. But a basic tenet of legal reasoning is that, in order to address that legal question, there needs to be an agreed-upon set of facts. Accordingly, a traditional motion to dismiss must accept as true all of the facts and allegations in an indictment or complaint and may argue only that those allegations do not rise to a crime or constitute a civil violation as a matter of law. As Neal Katyal and George Conway have argued, a number of senators who are considering what procedures to follow in this impeachment—and whether to call witnesses—are lawyers who should understand basic principles of the justice system. They should thus understand that they should vote to dismiss the impeachment charges without further evidence only if they conclude, as a matter of constitutional law, that the actions described in the House report, even if true, do not constitute a high crime or misdemeanor warranting removal from office.

If senators are not willing to accept the allegations stated in the House report as true but instead question the credibility of witnesses or note the lack of factual support for particular allegations, then they are no longer arguing about “innocence” or acquittal as a matter of law. At that point, facts undeniably become relevant and—crucially for the subsequent discussion of privilege—material to the ultimate decision on whether to convict the president. The trial is the place where the parties put those facts into evidence, whether or not all the facts were developed during the investigation. The judge or the jury then weighs that evidence and determines the underlying facts. Only after making those factual determinations does the judge or jury apply those facts to the allegations and the correct legal standard to determine whether the allegations are sufficiently supported.

Sen. Marco Rubio has asserted that “[t]he testimony & evidence considered in a Senate impeachment trial should be the same testimony & evidence the House relied upon when the passed the Articles of Impeachment” because the Senate’s “job is to vote on what the House passed, not to conduct an open-ended inquiry.” But as Orin Kerr noted, the Senate proceedings are “a trial, not an appellate argument based only on the record from the House”; “Federalist 65 says that the Senate’s trial ‘can never be tied down by such strict rules ... [i]n the delineation of the offense.”

Rubio’s approach is possible; the Senate could vote on the House articles without any additional information. That would be consistent, by analogy, with a motion to dismiss in a criminal trial. But senators are not required to do so. And, by the same analogy, if they do vote on a motion to dismiss based only on what is in the House report, they should assume the facts alleged are true and dismiss the articles only as a matter of law. It would be inconsistent with basic principles underlying our entire judicial system to contest facts or argue the factual record is insufficient but at the same time disallow any evidence about those facts.

Consider a hypothetical criminal case. Once indicted, the defendant has the option to move to dismiss the charges against him. He could argue, as a matter of law, that, accepting as true all the facts and allegations against him in the indictment, none of the alleged acts fulfilled the requirements of the relevant criminal statute. If a judge agreed with such a contention, then no evidence or witnesses would be necessary to resolve the case. But if the judge disagreed with that legal argument, then the case would go to trial. At trial, the parties would put on the evidence necessary to support or contest the allegations.

The same is true here. The appropriate standard for a motion to dismiss the articles of impeachment is whether the allegations in the House report, accepting all the underlying facts as true, warrant removal from office. What constitutes a “high crime or misdemeanor” sufficient to justify impeachment and removal has long been the subject of scholarship, debate, and controversy, including whether the Framers of the Constitution thought that only criminal conduct could rise to that level. Some observers have argued that Trump’s actions, as charged by the House, did constitute various crimes, such as bribery; others have argued that the question of whether the conduct is criminal is irrelevant; and still others assert his actions do not meet the definitions of particular crimes. The Constitution gives the Senate the solemn responsibility for making that determination.

If the lawyers in the Senate remember the basic distinction they learned in law school between facts and law, however, they cannot vote in favor of a motion to dismiss without first explaining their view that the actions described in the House report, even if true, do not warrant removal from office. But, to date, I have not seen many senators take that question head on. Under the Clinton impeachment rules, the president and the House would both have the opportunity to present opening statements before a potential motion to dismiss and to make whatever arguments they believe appropriate. Senators sitting as judge and jury of this impeachment trial, however, should adhere to the basic premise of the American judicial system. If the president’s lawyers dispute the facts alleged in the report or argue that the facts are incomplete, then fact witnesses and documentary evidence would be both relevant and required. A senator should vote to dismiss the charges before seeing that evidence only if, admitting as true all of the House’s allegations and factual record, she decides those allegations do not warrant removal from office. There is no middle road.

Would Witnesses Appear or Claim Executive Privilege?

Even if a witness is required to appear in a trial, however, certain privileges or immunities may prevent the witness from testifying about particular information. The plotline is familiar on shows like Law & Order or other legal dramas: A key witness heard a confession or knows a vital piece of information about a crime, but a privilege—such as the attorney-client, spousal, or priest-penitent privilege—thwarts the prosecutor’s ability to present that crucial evidence to the jury.

An initial question here, however, is whether the witnesses other than Bolton would even appear. The White House, supported by the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), relied on various constitutional arguments to direct all four of the relevant witnesses not to appear in the House. Bolton has now indicated he will nonetheless comply with a Senate subpoena. And Duffey would almost certainly have to appear. In the House inquiry, he refused to comply with a subpoena for a deposition solely because agency counsel would not be allowed to attend, and the House did not subpoena him to appear for public testimony at which he could have been accompanied by agency counsel. Assuming the Senate subpoenaed him for public testimony or, if it conducted a deposition, allowed government counsel to attend, Duffey would no longer have any basis for refusing to appear.

But the White House could again direct Mulvaney and Blair not to appear at all on the basis of testimonial immunity. Unlike the litigation that would likely have been required to force their testimony in the House inquiry, however, the Senate itself could vote on the validity of that immunity claim. As congressional experts have explained, Chief Justice John Roberts, presiding over the trial, would probably not be the one to decide their immunity or any privilege claim; ultimately, 51 senators are likely necessary to require the testimony. (The question of what happens in the event of a tie is more complicated, but in general, a 50-50 tie means a motion fails—though Roberts could potentially vote to break a tie in some circumstances.) As NPR’s Nina Totenberg put it, “under Senate rules, it is the senators themselves who have the first and last word.”

Accordingly, unlike the procedures that would have applied in the House, in the Senate the judge of the claim would be the full chamber. And a vote overruling any immunity or privilege claim would, by necessity, be a bipartisan one. Democrats would need three Republican senators to force a tie and four for a 51-vote majority. In the House, the Democratic chairman alone ruled on whether to recognize the claimed privilege or immunity. If Mulvaney and Blair were both confronted with a bipartisan Senate ruling that they must appear in the impeachment inquiry, they may be less willing to refuse to comply than they were in the House. That would be particularly true if the same Senate majority subsequently scheduled a vote to hold Mulvaney and Blair in contempt for their refusal to appear. In addition, if the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit were to issue a decision rejecting McGahn’s immunity claim, on which it recently heard oral arguments, that opinion could provide further impetus for Mulvaney and Blair to abide by the Senate subpoena rather than the White House’s direction.

If all the witnesses appeared, then, or at least Bolton and Duffey appeared, would executive privilege restrict their testimony? Relatedly, if Schiff gets his demand that the Senate subpoena documentary evidence as well—such as the unredacted emails between Duffey and Blair that Just Security reported on—would the executive branch be able to withhold them on the basis of executive privilege? This is where the doctrine of executive privilege, as developed and practiced by the executive branch currently, makes things very interesting—and very uncertain.

In interviews, Trump has indicated he will invoke executive privilege to prevent Bolton from testifying “for the sake of the office.” And according to at least one expert on Senate procedure and impeachment, there are no Senate rules governing an assertion of executive privilege during impeachment.

To me, there are two routes an invocation of executive privilege could take: a traditional assertion of the qualified executive privilege that would likely be overcome by the Senate’s need for the testimony to fulfill its impeachment duty or, more likely, a prophylactic “assertion,” that is not an assertion at all but an absolute prohibition on revealing anything even potentially privileged in order to protect the president’s authority to assert privilege later on.

The latter course is the one on which the White House has largely relied to date and reflects what I have called the executive branch’s development of a “prophylactic executive privilege” over the past few decades. (I describe that history in depth in a draft paper on executive privilege.) If the Senate permits the executive branch to rely on this privilege in the context of an impeachment trial, as the House largely did, it would represent an extraordinary consignment of constitutional authority from the legislature to the executive.

Under this approach, the White House would likely send the witnesses a letter informing them that aspects of their testimony are protected by executive privilege and that they are not authorized to disclose such information because only the president has the authority to waive that privilege. For example, during the House impeachment inquiry, a letter from the Pentagon informed Defense Department official Laura Cooper “of the Administration-wide direction that Executive Branch personnel ‘cannot participate in [the impeachment] inquiry.” And in one of the letters sent to counsel for witness Fiona Hill, a former National Security Council official, the White House reminded Hill of “continuing obligation not to reveal classified information or information subject to executive privilege,” including “the content of communications between the President and foreign heads of state and other diplomatic communications.” Similar letters have been sent to officials in the past—typically former officials over whom the administration has little control, including former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates. These officials have complied to various degrees but traditionally have respected as valid confidentiality concerns such as disclosure of classified information or presidential communications.

Under the executive branch’s view, executive privilege is not itself a privilege at all, but a conglomeration of “components,” or individual privileges. National security information, diplomatic communications, communications with the president, and internal executive branch deliberations represent various “components” that executive privilege ultimately protects. The White House would presumably instruct the officials not to reveal information falling into any of these categories without authorization from the president, asserting the executive branch’s view that the president has the sole constitutional authority to control the dissemination of that information and to control whether it goes to Congress. The president would thus not need to assert executive privilege for the White House to write such a letter. His authority to ultimately assert privilege would form the sole basis for the command, and the direction would be justified as prophylaxis, the need to protect the president’s authority to make such an assertion.

Clearly, the testimony of the four witnesses identified by Schumer would implicate these components generally. Bolton’s and Mulvaney’s testimony about the relevant events would almost certainly involve discussions with the president and diplomatic communications and negotiations. Blair’s and Duffey’s testimony may also involve presidential communications, at least under the executive branch’s broader view of that component, but it would almost certainly touch on internal deliberations implicating the deliberative process component of executive privilege. Indeed, the fact that OMB redacted information from emails between Blair and Duffey about the president’s direction and the hold on the aid to Ukraine under exemption 5 of FOIA indicates that OMB determined the information under those redactions was protected from release under FOIA by presidential communications or deliberative process. That necessarily means, at least for purposes of the executive branch, that the information implicates executive privilege.

If the White House chose this approach during the Senate trial and the witnesses complied with its directions, the trial would proceed something like the following. Bolton or the other witnesses would appear if subpoenaed by a Senate majority but decline to answer questions about any material potentially covered by executive privilege because they had been instructed not to divulge such information by the White House. They would thus not be able to testify about any information related to the executive branch’s internal deliberations, about the president’s communications or the advice they provided him, about the diplomatic negotiations with Ukraine or other countries, or about anything related to national security, including classified information. In short, they would probably not be able to say anything that is not already public. That is the reason I wrote that the litigation over McGahn’s claim of immunity meant little in terms of forcing his testimony; executive privilege means that, even if the House prevails and the courts reject the immunity claim, McGahn remains unlikely to testify about anything that is not already public.

The additional wrinkle—and, to me, the problematic aspect of the executive branch’s prophylactic privilege—is that the Senate would have no way to overcome those privilege claims. In a normal trial, when a qualified privilege is asserted to block testimony, it may be overcome by the other side’s interest in the information by applying the appropriate balancing test. But, by relying on the potential assertion of privilege, the president would never have to assert privilege; nor would the witness. The president would be relying solely on his authority to assert privilege eventually—and his purported corollary authority to control the dissemination of all information protected by executive privilege—to direct the witnesses not to testify. And the witnesses would be relying on that direction, not asserting privilege. There would be no balancing because there would be no assertion to weigh against the Senate’s interests.

This tactic is not new. Attorney General Jeff Sessions frustrated senators by refusing to answer questions about his conversations with Trump on the basis of executive privilege despite the fact that there had been no assertion of privilege. And past officials from both parties have done the same, invoking the “confidentiality” interests underlying the components of executive privilege to refuse to provide documents or testimony even if there has been no formal assertion of executive privilege. Under current doctrine, only when a congressional committee schedules a vote to hold an individual in contempt will the executive branch consider an actual privilege assertion.

But the tactic would be unprecedented in an impeachment trial. And the Senate should not abide it. The House largely allowed the executive branch to rely on this type of absolute prophylactic doctrine, making that reliance the basis for the second impeachment charge based on obstruction of Congress rather than addressing the substance of the White House’s constitutional arguments or taking the disputes to court. The Senate should not do the same.

That is not to say that the Senate should prevent Trump and the White House from asserting executive privilege. They can let his counsel present their arguments that it should apply. But they should require that the president assert executive privilege and defend that assertion if he seeks to block testimony by the witnesses rather than allow the executive branch to avoid such an assertion—and the balancing inquiry it necessitates—with prophylactic rationales. If a witness claims he cannot answer a question or an official claims he cannot turn over documents because of the president’s direction, and a Senate majority exists to force that testimony or the specific documents, the majority should vote to direct the individual to answer specific questions or turn over the documents and warn the witness that he will be held in contempt if he continues to refuse to do so. The official, faced with a bipartisan majority requiring his testimony or documents, may at that point relent and spurn the White House’s direction—for the same reasons that Mulvaney or Blair may appear if subpoenaed by a bipartisan Senate majority despite a contrary White House direction.

But the official could also, at that point, continue to abide by the White House’s direction and claim a lack of authority to reveal information protected by privilege because the president has not yet determined whether to assert privilege. Once a contempt vote has been scheduled, however, the executive branch—at least under current doctrine—must assert executive privilege over particular information in order to protect the individual from liability. Absent such an assertion, the official would have no defense to a subsequent prosecution for contempt of Congress, whether in this administration or a subsequent one. Moreover, in this case, it does not appear a “protective” assertion of executive privilege, another prophylactic doctrine that would provide the witness an absolute defense, is possible. As long as the Senate is specific about the questions to which it seeks answers or the documents it requires, the president would presumably have the opportunity to consider whether to assert privilege in response to those questions and over those documents. The sole rationale for a protective assertion would be to give him time to review a substantial number of documents or information to consider privilege.

In other words, by voting to require specific testimony or documents and threatening contempt if the officials refuse to comply, the Senate could force the president to decide whether or not to formally assert executive privilege. If faced with recalcitrant witnesses and a White House willing to play hardball, that approach may be the only way for the Senate to force an actual assertion. The Senate could then vote on whether to recognize that assertion or not. And an actual assertion is the only way the Senate can force the executive branch to grapple with its compelling interest in precise factual information during an impeachment trial.

In a footnote in OLC’s Nov. 1, 2019, opinion supporting the refusal of Duffey and other witnesses to comply with deposition subpoenas, the office recognized that past executive branch precedents have “acknowledged that Congress’s interest in information in connection with impeachment may be stronger than in the oversight context.” But, despite the White House’s repeated refusals to comply with the House’s impeachment inquiry, OLC has never had to take on that issue and fully explain why the relevant executive branch interests here outweigh Congress’s need. Given the history noted by OLC in passing and the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Nixon, that would be a very hard explanation to provide. If a majority of the Senate decides to foreclose additional evidence, senators should be forced to vote to accept that explanation—and endorse on the record the resulting demotion of the Senate’s constitutional responsibility to sit in judgment over an impeachment trial beneath general confidentiality interests of the executive branch.

Although I am not an expert on congressional rules or procedures, the Senate would also seem to have additional procedural possibilities to ensure the White House cannot rely on prophylactic doctrines. One mechanism could be a procedural rule requiring a formal assertion from the president for any claim of privilege to be recognized. There is also the possibility of judicial involvement, even if remote. If one of the witnesses indicates his willingness to testify despite a contrary direction by the White House, the Justice Department could ask a court to enjoin the individual from testifying on the basis of executive privilege. The posture would be similar to the cases about Trump’s financial records that are now pending at the Supreme Court—except in those cases Trump sued in his private and corporate capacities and executive privilege was not the basis for the claim. The Justice Department has only once filed a suit to enjoin the provision of information to Congress on the basis of executive privilege, when it sued AT&T asking the courts to enjoin the company from turning over wiretap records in response to a congressional subpoena. President Ford had claimed executive privilege and directed AT&T to refuse to comply on the basis of a contractual confidentiality provision. But AT&T indicated it intended to comply absent a court order prohibiting it.

The filing of such a suit is unlikely, particularly because it would largely undercut the Justice Department’s current position that the courts should stay out of disputes over information between Congress and the executive branch. Any such suit would likely require an assertion of executive privilege, however; otherwise, the executive branch would not have a recognized constitutional interest to protect, only a potential one. It seems likely that the courts would require the president to assert privilege formally, attesting that the disclosure of the specific information sought by the Senate would damage the country, which is the traditional requirement for an assertion of executive privilege and the assertion that the president made in the AT&T case. Thus, even if the Justice Department did file such a suit, it would immediately raise the same balancing inquiry that heavily favors the Senate in this context. And that litigation should not take too long, particularly if the Supreme Court were willing to step in early as it did during Watergate. Unlike cases in which a committee of Congress sues the executive branch, the incentive to have a quick resolution of that type of litigation would be on the executive branch; they would need a court order rapidly if the individual stood willing to testify absent a contrary directive from a court.

Even if achieved by other means, however, forcing a formal assertion of privilege is vital. As I have described, only a formal assertion of privilege requires the executive branch to balance congressional interests. And, in impeachment, those interests are at their apex. In the course of the impeachment process itself, it is hard to imagine a point at which Congress’s interest in the specific information would be more elevated than in an impeachment trial in which a majority of senators had determined they needed to hear specific testimony to decide whether or not to convict the president.

The individual witnesses will play an enormous role in ensuring that balancing occurs. They will undoubtedly have to wrestle with difficult questions of obligation and constitutional law. But even if they believe the executive branch’s interests outweigh the Senate’s need for the information and that a claim of executive privilege is thus appropriate, they can and should ensure that this legal analysis underlies their refusal to testify, rather than a prophylactic doctrine that takes no account of congressional interests.

To do so, they need only require that the executive branch assert privilege if it wishes them to refrain from particular testimony. That would not be unprecedented. Take, for example, the former IRS employee deposed as part of a Republican-led inquiry of the Affordable Care Act during the Obama administration. Executive branch officials had instructed the former official not to answer questions that might implicate executive privilege, but, as he stated to the committee in his deposition: “I posed to [the administration] whether or not they were planning to go to court and assert executive privilege around the deliberative process, [but] I did not receive an answer. ... [W]e are here under subpoena. I have no privilege assertion from the executive branch, which is the reason why I'm here to answer any of your questions without limitation.”

The Supreme Court’s decision about the Watergate tapes in United States v. Nixon forecloses any contention that general confidentiality interest in presidential communications or internal deliberations would be sufficient to outweigh the Senate’s duties to determine whether to convict the president. Perhaps there could be some information that is so sensitive or that is classified that it should not be released publicly, but the Senate could go into closed session to hear that. Or the Senate could focus narrowly on conversations with the president and others relevant to the impeachment charges and avoid more sensitive areas.

In short, executive privilege as understood in United States v. Nixon and as acknowledged by OLC across administrations is a qualified privilege. And, in an impeachment inquiry, Congress’s needs almost certainly overcome that privilege. Thus, even if OLC is right that the privilege “applies”—which I disagree with as a theoretical matter—it is overcome and cannot be utilized to withhold information.

If the Senate decides to call witnesses and the White House nevertheless attempts to block their testimony on the basis of executive privilege, the difficulty in the Senate thus will not be in coming up with a legal argument to overcome that privilege. Nor will it likely be in convincing a majority of the Senate or the American people that the Senate needs the information. As noted, the fact that the Senate has decided to call the witnesses at all means their testimony is necessary to make the determination of whether the facts support the allegations. If executive privilege comes into play, it means a majority of the Senate would have decided that the testimony or information sought is material to the decision of whether to convict the president. Senators might be tempted to vote to subpoena witnesses but then vote against requiring them to testify after the president’s attorneys raise executive privilege. But to do so would be logically incoherent.

The primary problem confronting the Senate, at least initially, will be how to deal with the layers of prophylaxis surrounding executive privilege in order to get to the fundamental weighing of interests it requires. The House ultimately chose not to fight that battle. And it may prove difficult to garner a majority of senators to do so, particularly if they do not fully comprehend the breadth and implications of the White House’s position that it need not consider congressional interests.

If senators exercising their solemn duty to sit in judgment over the impeachment articles determine that calling witnesses is necessary, they should also understand that penetrating the layers of prophylaxis is necessary for the same reasons. Unlike a FOIA response, which does not require balancing any interests in the information, executive privilege is not the blanket authority to withhold information that potentially implicates the confidentiality interests it protects. It is a qualified authority that must take into account Congress’s interests. In an impeachment inquiry, Congress’s need for precise factual information is at its zenith.

If the president and the White House decide to try and prevent that factual information from getting to the Senate by utilizing executive privilege, they should at least be forced to undertake the balancing executive privilege requires and provide a legal argument as to why the Senate’s need for the information is not sufficient to overcome that qualified privilege. Because of the nature of impeachment, I think any such argument would be extremely tenuous. But the Senate would ultimately get to decide. Faced with such an argument, it could overrule the privilege claim and receive the evidence necessary to perform its constitutional task.

****

The only reason factual evidence would not be necessary in the impeachment trial is if the Senate believes that the House allegations, even if all true, do not warrant removal from office. If, however, a majority of the Senate believes additional evidence is necessary to fulfill its solemn constitutional responsibility to determine whether the president committed a high crime or misdemeanor, then the White House may attempt to rely on its prophylactic doctrines of executive privilege to prevent certain testimony or the provision of particular documents. But the executive branch should not be allowed to rely on executive privilege without considering the Senate’s overwhelming interest in receiving that information—a need that history and Supreme Court precedent indicate almost certainly outweighs any general confidentiality interests the White House and the Justice Department may assert.

If the White House attempts to utilize its prophylactic doctrines, both the Senate and the individual witnesses and officials have the means to fight back and ensure that the Senate’s interests are considered. And if the White House and OLC then conclude that the Senate’s need for the information in an impeachment trial does not outweigh the executive branch’s general confidentiality interests and asserts executive privilege, a simple majority of the Senate can overrule that determination. What’s more, a majority of the Senate will have already made that determination: By voting that the witnesses or documents are necessary to fulfill the Senate’s constitutional responsibility, the majority has already decided that the Senate has a specific need for that information in order to perform its constitutional responsibilities. In that circumstance, the qualified executive privilege protecting undifferentiated confidentiality interests cannot prevent the disclosure of the information.

To me, the debate over witnesses and executive privilege in the Senate impeachment trial is relatively simple. If a majority of the Senate believes particular witnesses or documents are necessary to perform their constitutional task, then the qualified executive privilege is not available. The Senate’s need for the information in an impeachment trial is too compelling. But the executive branch’s constitutional doctrines in this area are complex and could easily obscure that simple inquiry. Senators, witnesses and executive branch officials should not allow that to happen.