The Tyler Doctrine and War Powers

The Millard Fillmore administration’s diplomatic machinations toward Hawaii are a curious example of the executive branch regarding itself as constitutionally empowered to threaten war but constrained from unilaterally carrying out that threat.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

On this day in 1842, President John Tyler announced to Congress that the United States would henceforth protect the Hawaiian (or Sandwich) islands from European control. Like its older and better-known cousin, the Monroe Doctrine, this Tyler Doctrine posed a challenge for American diplomacy and constitutional war powers: The president had vast power to threaten military acts of war but generally lacked authority to carry them out absent congressional approval, so maintaining the credibility of American threats and commitments could get tricky.

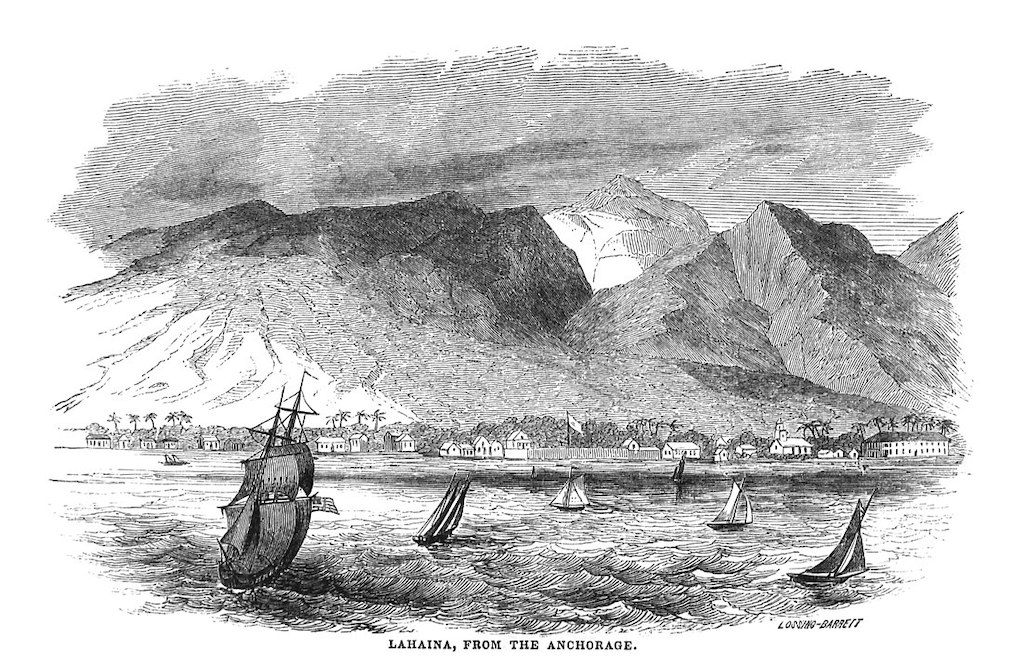

In the 1840s, the Hawaiian islands were a crucial transit point for growing American commercial trade with Asia. They were also a major spot for American religious missionary activities. The weak government there, however, was vulnerable to pressure or even subjugation by France or Britain, which had possible designs on the territory.

Similar to the way President James Monroe’s 1823 message to Congress addressed Latin America, Tyler began his 1842 statement by noting that the Hawaiian islands were much closer to North America than to any other continent, and by outlining important American interests there. Should a foreign power subvert the Hawaiian government’s independence, he proclaimed, the United States would make “a decided remonstrance.” Although this diplomatic phrase might not sound like much, neither did Monroe’s earlier language, but the implication to European states was clear: The United States would regard European control or interference in these islands as a hostile act.

The main architect of the Tyler Doctrine was Secretary of State Daniel Webster. About a decade later, he became secretary of state a second time, for President Millard Fillmore. In the early 1850s, U.S. interest in the Hawaiian islands was growing fast following the acquisition of California and Oregon—and French diplomatic and military pressures on the Hawaiian government were growing, too. The Hawaiian government looked to the United States for reassurance against possible French designs on its sovereignty, and this led to one of my favorite diplomatic maneuvers by Webster, reflecting his efforts to square strict interpretation of constitutional war power allocations with strategic imperatives. (I previously wrote about Webster’s clumsiest effort to do so in the same period here on Lawfare.)

In 1851, Webster learned that the U.S. envoy in Hawaii had privately assured its king that if French forces assaulted the islands, the United States would protect it by accepting its voluntary transfer of sovereignty and using naval power to defend the islands. Webster took seriously the French threat to Hawaii but regarded the U.S. envoy’s assurances as not only beyond the boundaries of U.S. policy but also probably beyond what the executive branch could constitutionally commit. On July 14, 1851, Webster sent the envoy two letters to manage the situation, one that was also sent to the French and Hawaiian governments and one that was to be kept confidential.

The first letter reiterated the Tyler Doctrine, or U.S. policy to preserve Hawaii’s independence from European states. It closed with a strong message about American military power: “The Navy Department will receive instructions to place, and to keep” naval forces in the Pacific “in such a state of strength and preparation, as shall be requisite for the preservation of the honor and dignity of the United States, and the safety of the government of the Hawaiian Islands.” Webster wanted to brandish this naval power very visibly to European states.

In the additional confidential instructions to the American envoy in Hawaii, however, Webster was emphatic about the limits of executive powers to actually use these forces. “In the first place I have to say,” he began, “that the war-making power in the Government, rests entirely with Congress; and that the President can authorize belligerent operations only in the cases expressly provided for by the Constitution and the laws.” He continued: “By these, no power is given to the Executive to oppose an attack by one independent nation, on the possessions of another.” Firing on a French vessel because it attacked Hawaii, for example, would be an act of war beyond the president’s limited authority.

In an intriguing line, Webster then stated that, in such cases, “where the power of Congress cannot be exercised beforehand, all must be left to the redress which that body may subsequently authorize.” I strongly suspect that Webster meant not simply that it would be politically or practically difficult to get preauthorization for force from Congress, but that it was not constitutionally permitted. Webster had in earlier times expressed doubt whether Congress could conditionally delegate its war initiation powers to the president, arguing that these powers had to be exercised completely by Congress.

Webster further instructed the envoy to keep the French in the dark about these constitutional limits: “[I]t is not necessary that you should enter into these explanations with the French Commissioner or the French Naval Commander.” In other words, it would be better for the French government to assume that the president had constitutional authority to back up his threats.

Just to drive home the constitutional points—after all, this envoy had already far overstepped his prior instructions—Webster summed them up this way:

In my official letter of this date, I have spoken of what the United States would do in certain contingencies. But in thus speaking of the government of the United States, I do not mean the Executive power, but the government in its general aggregate, and especially that branch of the government which possesses the War making power. This distinction you will carefully observe, and you will neither direct, request or encourage any Naval officer of the United States in committing hostilities on French vessels of War.

Webster further directed the envoy to revoke any pledge to assume Hawaii’s sovereignty in the event of French attack. He stated that such a decision would need to be made in Washington, not by diplomats abroad.

In the end, Webster’s efforts were mostly successful in wielding general threats of force while privately holding to strict limits on executive power: The Hawaiian government felt gratefully reassured, and the French government emphatically disclaimed any aggressive designs on Hawaii. Webster’s threats may even have gone too far, as the French foreign minister took umbrage at the insinuation of hostile intentions. In a memorandum to the French ambassador to the United States, the foreign minister also sneered tartly: “I am not so unacquainted with the character of the federal constitution, not to know, that, if the document in question, had contained, according to its literal sense, an eventual threat of war it would have exceeded the prerogatives of the executive power.” Apparently the French were quite aware of American constitutional constraints and the gap between the president’s diplomatic threats and legal capacity to make good on them.

* * *

A century later, in 1950, the Truman administration defended the president’s unilateral military intervention to protect South Korea based partly on a claim of historical executive branch practice, stretching back to the early republic, of military action without congressional authorization. The 1851 Hawaii episode is a contrary data point—of the executive branch regarding itself as constitutionally constrained from unilateral military intervention to protect another country from aggression. It does not show up in catalogs of historical “practice,” though, because intervention turned out to be unnecessary.

For a more general discussion of the constitutional power to threaten force and the relationship between allocations of war powers and international signaling, see my article here.